Every last buggin' gang on the whole buggin' street

West Side Story, the highest-grossing film of 1961 and the winner of that year's Best Picture Oscar (one of a whopping ten awards it one at that ceremony; only three films have ever won more*), has been a duly-anointed classic for so long - pretty much since 1961, really - that it can be hard to appreciate what a complicated spot it occupies in cinema history, what a strange and prickly transitional movie it is. The '60s were a decade in which the Hollywood film industry, beset by the end of the vertically-integrated studio system and the rise of that scrappy little upstart, television, tried to combat its own high-speed decline into irrelevance with a desperate gambit to make the kind of things you could only get at the movies: massive bloated epic monsters, huge overstuffed superproductions full of big sets and costumes. Many of the most sprawling examples of these were musicals, and West Side Story is not merely example of one of these: it is arguably where the trend started.

At the same time, the dying carcass of the studio system meant that filmmakers could start to really hone their knives, indulging in nervy, modern-feeling stories of grit and ugliness. Stories that, in content and even just in tone were too hard-edged for the era when the Production Code still had all of its teeth. And West Side Story is an example of one of these, also. It was adapted from the 1957 musical with music by Leonard Bernstein, lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, and a book by Arthur Laurents (the film's screenplay was by Ernest Lehman), and that was itself a seismic, revolutionary object when it hit Broadway; the film had to sand off some of the stage show's edges, but it was coming to an even more conservative medium, and had its own degree of "hell yeah, we can do this now" vitalism, thanks to co-directors Robert Wise and Jerome Robbins.

This combination of contradictory impulses and energies - the square and the edgy; the overblown and the wiry - could easily result in some kind of slithery, unpredictable, even dangerous film object. I am not sure that it does so. I should own up to all my biases: I'm not actually very fond of the show (if I were a Tony awards voter that season, I'd have checked off The Music Man for Best Musical without a second thought - as indeed the actual Tony voters did), and having read Sondheim's book of collected lyrics, Finishing the Hat, I find his generally peevish feelings towards his writing here very persuasive (this was his first Broadway show, and he felt that he got pushed into more flowery, poetic writing by Bernstein than he was comfortable or happy with). It's a bit of a strained attempt to map Romeo and Juliet to the ethnic tensions of Manhattan street gangs in the 1950s, one that offers a couple of undernourished, bland protagonists. And while Robbins's choreography deserves it legendary, groundbreaking reputation (the show was mostly Robbins's idea, for that matter), I have to confess that "dancing gangs" as a concept in such a deadly-serious narrative has never entirely worked for me, and always feels like something the show has compensate for, rather than something that makes it stronger.

To its credit, the film does in fact compensate for it, about as well as I could imagine it being done. West Side Story opens with what isn't merely its best sequence, but the best sequence in any musical of the 1960s, maybe with the exception of the title number from The Sound of Music (which works in part for the same reason, and was also directed by Wise, who presumably learned some tricks here). After the overture, at least, and it's a helluva good overture; while I am happy to cosign Sondheim's reservations about the lyrics, it's tough to say anything against Bernstein's music, which is tetchy and sweeping and violent and poppy all at once, a terrific attempt to bring post-WWII symphonic music into an accessibly romantic idiom for Broadway. And while Bernstein was apparently unhappy with the new orchestrations done for the movie, thinking it too "big", the grand scale of the music fits so nicely with the Super Panavision 70 cinematography and the general feeling of opulence in the production that I admit to finding it very fetching.

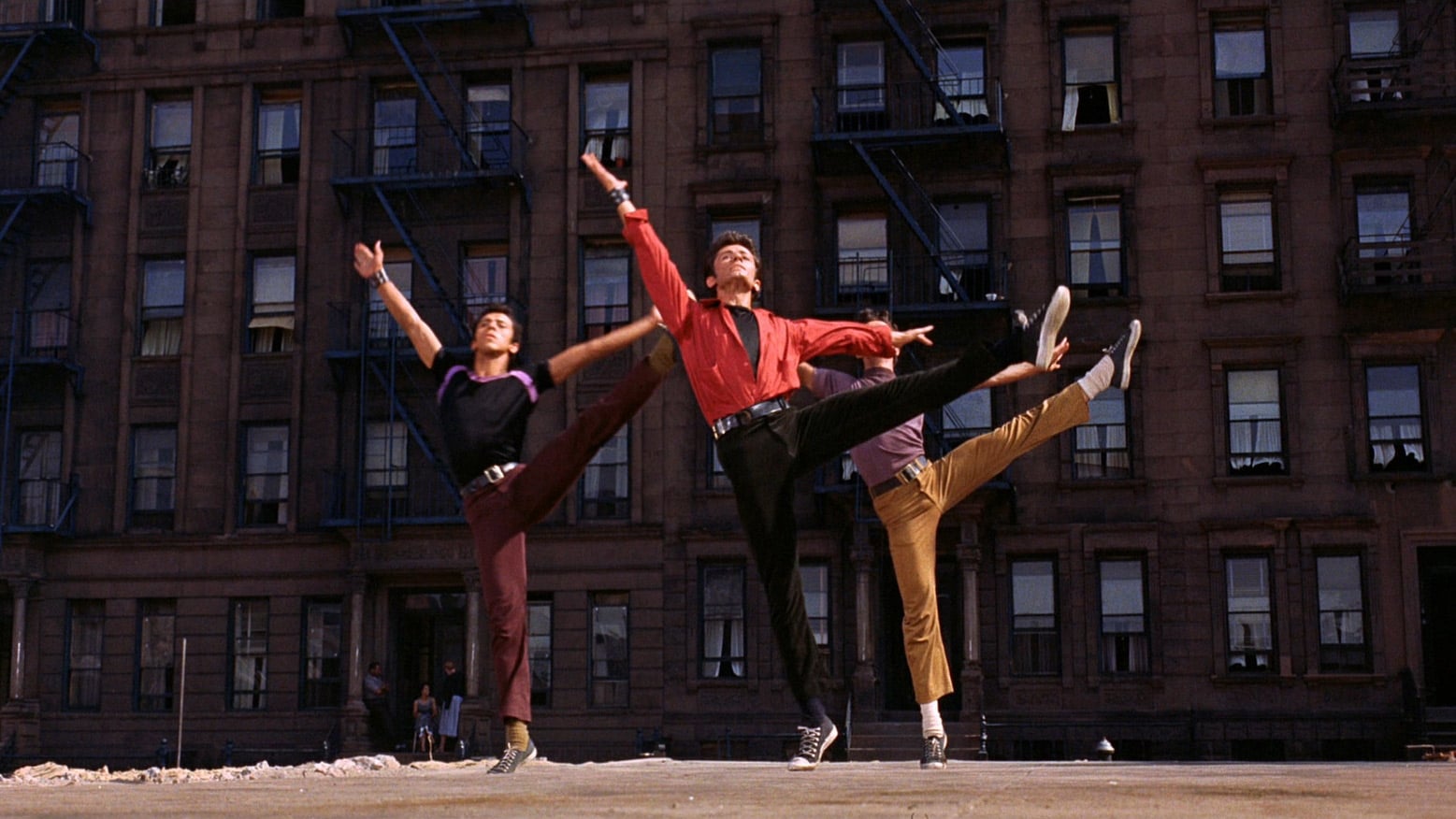

Anyways, after the overture: a series of helicopter shots over Manhattan, pointing more or less straight down, rendering the city blocks as geometric shapes, and the skyscrapers as weird, unstable fragments. It is astonishingly modern for a film made in 1961; it would have still been striking and strange 20 years later or more. Hell, it's still striking and strange. And as we see this, we hear the distinctive, tuneless whistle that opens the show, a hollow echo. Eventually, the scale closes in on a playground, where we're introduced to the main conflict of the movie: a turf war over a few blocks of aging asphalt, fought between the Jets, a gang made up of second- or third-generation European-Americans and the Sharks, a gang made up of Puerto Rican immigrants. This is all communicated in the form of a ballet, with the Jets stalking around and freaking people out before running into the Sharks, whereupon both groups chase each other down the alleys and into the streets, complete with all the iconic things Robbins concocted: finger snapping, sinuous group movements that feel like pack hunters trying to corral their prey, and these big Y-shaped stretches that I honestly don't know if I entirely buy. But damned if the film doesn't make me want to buy it. It is generally understood that Robbins (a newcomer to the movies) directed the musical numbers while Wise directed the dialogue scenes, but also that Robbins was fired as a result of cost and schedule overruns. I don't know whether this sequence, shot on location in New York, was filmed before or after he left; either way, it's a masterpiece of combining dancing with a physical space, and it is that physicality that really, desperately matters here. The tangible, actual fact of New York's streets is indescribably important to this sequence - the dirty, aged textures of walls and asphalt, and the sharp white light of the real-world sun, which cinematographer Daniel L. Fapp allows to just slightly overexpose the highlights on the actors' faces. It is, unmistakable, the real world, and the combination of that real world with the stylised abstractions of the dancers' movements is one of the most extraordinary things in the history of musical cinema. It creates an electrifying, startling tension between the highly artificial theatricality of the dance and the flat, disaffected, documentary rawness of the footage, holding a tension in place just as fraught as the one between the gangs.

The problem with it is that, at about the 18-minute mark, we're done with location footage (and even by that point, there has been for sure one and possibly two locations on a backlot or soundstage), and I just do not see how it's possibly to argue that the film doesn't suffer for the change. West Side Story mostly takes place on sets that look like sets, and that's not especially a problem per se; but the story very much wants to be taken seriously as something gritty and rough and real, and that's a little tricky to handle when it looks so stagey. It's a lot tricky when the film has, before introducing its soundstages, given us such extraordinary location footage that those soundstages end up feeling that much more obviously, vividly fake. And this is where the gap between Robbins the neophyte and Wise the old hand starts to become especially visible. Wise's scenes, to be very clear, look like they're on sets. But he's moving the camera around in those sets, and blocking the actors at the same time, to create nice compositions and a strong sense of cinematic space. It's dynamic and alert, full of acute angles that keep the tension up. It's easy to recall, watching this film, that Wise got his start as a director in Val Lewton's horror unit at RKO; in the best moments (which are backloaded, as the action gets darker and more violent), his directing is pushing us in the direction of expressionism, using the lines and shapes of the set as graphic elements to surround, threaten, and ultimately liberate his characters.

Robbins, meanwhile, shoots like he's got a camera set up in the audience and he's treating the movie like a proscenium stage. To an extent, his ass is bailed out by editor Thomas Stanford, whose work on the musical numbers is some of the best-regarded cutting in Hollywood history; that's probably overrating it a touch, but there's no mistaking how much the editing is responsible for speeding up the fast moments and letting the slow moments breathe, while also focusing attention on the groups of dancing bodies such that we always feel the most significant moments land hardest.

That gets us quite a way through the film without even touching on the plot or characters or acting, and I've ignored that at least partially on purpose. The acting in West Side Story is, to be blunt, a huge bummer. The unambiguous standout, by an extravagant margin, is Rita Moreno, who plays roughly the equivalent to the Nurse in Romeo and Juliet, as Anita, the girlfriend of the Juliet-character's brother and the only one who knows the lovers' secret. It's probably not a coincidence that she's the only Puerto Rican actor with a substantial role, but whatever does it, she has both the right high-pitched theatricality and the most thoughtfully small reactions and business. It's both a grandiose performance and one that laser-targets the emotional currents of the second half when things turn dark and she begins to tighten Anita's blowsy frustration into ice-cold anger. For the honor of first runner-up, I also quite enjoy Russ Tamblyn's work as the sarcastic, arrogant leader of the Jets, Riff; the role thrives from the scuzzy charisma that Tamblyn was about to refine over a decade and change in exploitation films, but even here in a prestige production, he does a great job of combining Hollywood melodrama and boots-on-the-ground story of antisocial teens; the one time he does his own singing is in the snarling, cynical "Gee, Officer Krupke" (secretly the best song in the show; or at any rate, the one with the best lyrics), and that's the ideal showcase for the self-pleased oiliness of his character work in the film.

Outside of those two, I'm not sure if there's any performance that works at all. Most of the Sharks and Jets are just background filler, even the ones with more-or-less definite personalities. George Chakiris (like Moreno, an Oscar winner for the film, though unlike Moreno, he came nowhere close to deserving it) is a flat, unmodulated tough guy, and while he's good and the mechanics of dancing - as good as anyone in the film - he's not really acting though his dance. As the male lead, Tony, Richard Beymer has nothing to work with (Tony is an extremely drab part who gets stuck with the worst song in the show, "Something's Coming" - and I would be lying to you if I said that I actually like either of the second act love duets very much), and he offers nothing to compensate. As the female lead, Maria, Natalie Wood is a goddamn disaster, turning in what is unquestionably the worst performance I've seen her give. Playing a Puerto Rican role in brownface led Wood to make some downright apocalyptic choices for what to do with her voice, diving headlong into a garish accent - and then Marni Nixon, the famed "ghost singer" who also overdubbed Deborah Kerr in The King and I and Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady, has to come up with her own garish accent to try to match her. It doesn't land, and Wood's very wobbly attempt at lip-syncing makes it worse. But let us not just focus on Wood's voice, when her pantomime-broad physical performance is right there, mugging and clomping about.

The good news, I guess, is that West Side Story is so much more about its bold-faced emotionalism than its characters that it can somehow surviving having two bad performances in the leading roles. Bernstein's instinct towards a register of heightened romanticism and everything in big essentialist strokes, however much Sondheim would grow to regret the lyric-writing it obliged him to perpetrate, means that the music pushes the story forward with enough convincing pomposity that it's not really a problem if either the psychological or the sociological elements of the story fall flat. Which is good, because outside of Anita, they mostly do here. And Wise's directing creates such strong impressions of dramatic spaces that the film's visuals mostly match with its music. The result is that West Side Story somehow ends up being better than it actually is, if that makes sense; it works well enough as a holistic object that the failure of some of its constituent parts never does it too much harm. And the film's reordering of the musical numbers and slight shifting of plot beats helps that even more than the stage version: in particular, the delay of the rumble and swapping "Gee, Officer Krupke" and "Cool" both mean that the film's story gets to plunge straight ahead into tragedy and nighttime heaviness without any hiccups. I frankly don't think it's done very gracefully or artfully; The Sound of Music is distinctly more sophisticated filmmaking, handled by Wise with much more psychological nuance, despite coming from considerably spottier source material. But in fairness to West Side Story, this isn't about graceful, artful, nuanced people: it's about teenagers getting in over their heads, both in terms of romance and terms of their confidence that they can control their little patch of the world through bravado and swagger. Bold-strokes emotions and constantly forward-moving urgency are perhaps the right fit for this material, and while I do not, have never, and likely will never love this film, I do admit that it's easy to get swept away by the sheer muchness of it.

*Namely, Ben-Hur in 1959, Titanic in 1997, and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King in 2003)

At the same time, the dying carcass of the studio system meant that filmmakers could start to really hone their knives, indulging in nervy, modern-feeling stories of grit and ugliness. Stories that, in content and even just in tone were too hard-edged for the era when the Production Code still had all of its teeth. And West Side Story is an example of one of these, also. It was adapted from the 1957 musical with music by Leonard Bernstein, lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, and a book by Arthur Laurents (the film's screenplay was by Ernest Lehman), and that was itself a seismic, revolutionary object when it hit Broadway; the film had to sand off some of the stage show's edges, but it was coming to an even more conservative medium, and had its own degree of "hell yeah, we can do this now" vitalism, thanks to co-directors Robert Wise and Jerome Robbins.

This combination of contradictory impulses and energies - the square and the edgy; the overblown and the wiry - could easily result in some kind of slithery, unpredictable, even dangerous film object. I am not sure that it does so. I should own up to all my biases: I'm not actually very fond of the show (if I were a Tony awards voter that season, I'd have checked off The Music Man for Best Musical without a second thought - as indeed the actual Tony voters did), and having read Sondheim's book of collected lyrics, Finishing the Hat, I find his generally peevish feelings towards his writing here very persuasive (this was his first Broadway show, and he felt that he got pushed into more flowery, poetic writing by Bernstein than he was comfortable or happy with). It's a bit of a strained attempt to map Romeo and Juliet to the ethnic tensions of Manhattan street gangs in the 1950s, one that offers a couple of undernourished, bland protagonists. And while Robbins's choreography deserves it legendary, groundbreaking reputation (the show was mostly Robbins's idea, for that matter), I have to confess that "dancing gangs" as a concept in such a deadly-serious narrative has never entirely worked for me, and always feels like something the show has compensate for, rather than something that makes it stronger.

To its credit, the film does in fact compensate for it, about as well as I could imagine it being done. West Side Story opens with what isn't merely its best sequence, but the best sequence in any musical of the 1960s, maybe with the exception of the title number from The Sound of Music (which works in part for the same reason, and was also directed by Wise, who presumably learned some tricks here). After the overture, at least, and it's a helluva good overture; while I am happy to cosign Sondheim's reservations about the lyrics, it's tough to say anything against Bernstein's music, which is tetchy and sweeping and violent and poppy all at once, a terrific attempt to bring post-WWII symphonic music into an accessibly romantic idiom for Broadway. And while Bernstein was apparently unhappy with the new orchestrations done for the movie, thinking it too "big", the grand scale of the music fits so nicely with the Super Panavision 70 cinematography and the general feeling of opulence in the production that I admit to finding it very fetching.

Anyways, after the overture: a series of helicopter shots over Manhattan, pointing more or less straight down, rendering the city blocks as geometric shapes, and the skyscrapers as weird, unstable fragments. It is astonishingly modern for a film made in 1961; it would have still been striking and strange 20 years later or more. Hell, it's still striking and strange. And as we see this, we hear the distinctive, tuneless whistle that opens the show, a hollow echo. Eventually, the scale closes in on a playground, where we're introduced to the main conflict of the movie: a turf war over a few blocks of aging asphalt, fought between the Jets, a gang made up of second- or third-generation European-Americans and the Sharks, a gang made up of Puerto Rican immigrants. This is all communicated in the form of a ballet, with the Jets stalking around and freaking people out before running into the Sharks, whereupon both groups chase each other down the alleys and into the streets, complete with all the iconic things Robbins concocted: finger snapping, sinuous group movements that feel like pack hunters trying to corral their prey, and these big Y-shaped stretches that I honestly don't know if I entirely buy. But damned if the film doesn't make me want to buy it. It is generally understood that Robbins (a newcomer to the movies) directed the musical numbers while Wise directed the dialogue scenes, but also that Robbins was fired as a result of cost and schedule overruns. I don't know whether this sequence, shot on location in New York, was filmed before or after he left; either way, it's a masterpiece of combining dancing with a physical space, and it is that physicality that really, desperately matters here. The tangible, actual fact of New York's streets is indescribably important to this sequence - the dirty, aged textures of walls and asphalt, and the sharp white light of the real-world sun, which cinematographer Daniel L. Fapp allows to just slightly overexpose the highlights on the actors' faces. It is, unmistakable, the real world, and the combination of that real world with the stylised abstractions of the dancers' movements is one of the most extraordinary things in the history of musical cinema. It creates an electrifying, startling tension between the highly artificial theatricality of the dance and the flat, disaffected, documentary rawness of the footage, holding a tension in place just as fraught as the one between the gangs.

The problem with it is that, at about the 18-minute mark, we're done with location footage (and even by that point, there has been for sure one and possibly two locations on a backlot or soundstage), and I just do not see how it's possibly to argue that the film doesn't suffer for the change. West Side Story mostly takes place on sets that look like sets, and that's not especially a problem per se; but the story very much wants to be taken seriously as something gritty and rough and real, and that's a little tricky to handle when it looks so stagey. It's a lot tricky when the film has, before introducing its soundstages, given us such extraordinary location footage that those soundstages end up feeling that much more obviously, vividly fake. And this is where the gap between Robbins the neophyte and Wise the old hand starts to become especially visible. Wise's scenes, to be very clear, look like they're on sets. But he's moving the camera around in those sets, and blocking the actors at the same time, to create nice compositions and a strong sense of cinematic space. It's dynamic and alert, full of acute angles that keep the tension up. It's easy to recall, watching this film, that Wise got his start as a director in Val Lewton's horror unit at RKO; in the best moments (which are backloaded, as the action gets darker and more violent), his directing is pushing us in the direction of expressionism, using the lines and shapes of the set as graphic elements to surround, threaten, and ultimately liberate his characters.

Robbins, meanwhile, shoots like he's got a camera set up in the audience and he's treating the movie like a proscenium stage. To an extent, his ass is bailed out by editor Thomas Stanford, whose work on the musical numbers is some of the best-regarded cutting in Hollywood history; that's probably overrating it a touch, but there's no mistaking how much the editing is responsible for speeding up the fast moments and letting the slow moments breathe, while also focusing attention on the groups of dancing bodies such that we always feel the most significant moments land hardest.

That gets us quite a way through the film without even touching on the plot or characters or acting, and I've ignored that at least partially on purpose. The acting in West Side Story is, to be blunt, a huge bummer. The unambiguous standout, by an extravagant margin, is Rita Moreno, who plays roughly the equivalent to the Nurse in Romeo and Juliet, as Anita, the girlfriend of the Juliet-character's brother and the only one who knows the lovers' secret. It's probably not a coincidence that she's the only Puerto Rican actor with a substantial role, but whatever does it, she has both the right high-pitched theatricality and the most thoughtfully small reactions and business. It's both a grandiose performance and one that laser-targets the emotional currents of the second half when things turn dark and she begins to tighten Anita's blowsy frustration into ice-cold anger. For the honor of first runner-up, I also quite enjoy Russ Tamblyn's work as the sarcastic, arrogant leader of the Jets, Riff; the role thrives from the scuzzy charisma that Tamblyn was about to refine over a decade and change in exploitation films, but even here in a prestige production, he does a great job of combining Hollywood melodrama and boots-on-the-ground story of antisocial teens; the one time he does his own singing is in the snarling, cynical "Gee, Officer Krupke" (secretly the best song in the show; or at any rate, the one with the best lyrics), and that's the ideal showcase for the self-pleased oiliness of his character work in the film.

Outside of those two, I'm not sure if there's any performance that works at all. Most of the Sharks and Jets are just background filler, even the ones with more-or-less definite personalities. George Chakiris (like Moreno, an Oscar winner for the film, though unlike Moreno, he came nowhere close to deserving it) is a flat, unmodulated tough guy, and while he's good and the mechanics of dancing - as good as anyone in the film - he's not really acting though his dance. As the male lead, Tony, Richard Beymer has nothing to work with (Tony is an extremely drab part who gets stuck with the worst song in the show, "Something's Coming" - and I would be lying to you if I said that I actually like either of the second act love duets very much), and he offers nothing to compensate. As the female lead, Maria, Natalie Wood is a goddamn disaster, turning in what is unquestionably the worst performance I've seen her give. Playing a Puerto Rican role in brownface led Wood to make some downright apocalyptic choices for what to do with her voice, diving headlong into a garish accent - and then Marni Nixon, the famed "ghost singer" who also overdubbed Deborah Kerr in The King and I and Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady, has to come up with her own garish accent to try to match her. It doesn't land, and Wood's very wobbly attempt at lip-syncing makes it worse. But let us not just focus on Wood's voice, when her pantomime-broad physical performance is right there, mugging and clomping about.

The good news, I guess, is that West Side Story is so much more about its bold-faced emotionalism than its characters that it can somehow surviving having two bad performances in the leading roles. Bernstein's instinct towards a register of heightened romanticism and everything in big essentialist strokes, however much Sondheim would grow to regret the lyric-writing it obliged him to perpetrate, means that the music pushes the story forward with enough convincing pomposity that it's not really a problem if either the psychological or the sociological elements of the story fall flat. Which is good, because outside of Anita, they mostly do here. And Wise's directing creates such strong impressions of dramatic spaces that the film's visuals mostly match with its music. The result is that West Side Story somehow ends up being better than it actually is, if that makes sense; it works well enough as a holistic object that the failure of some of its constituent parts never does it too much harm. And the film's reordering of the musical numbers and slight shifting of plot beats helps that even more than the stage version: in particular, the delay of the rumble and swapping "Gee, Officer Krupke" and "Cool" both mean that the film's story gets to plunge straight ahead into tragedy and nighttime heaviness without any hiccups. I frankly don't think it's done very gracefully or artfully; The Sound of Music is distinctly more sophisticated filmmaking, handled by Wise with much more psychological nuance, despite coming from considerably spottier source material. But in fairness to West Side Story, this isn't about graceful, artful, nuanced people: it's about teenagers getting in over their heads, both in terms of romance and terms of their confidence that they can control their little patch of the world through bravado and swagger. Bold-strokes emotions and constantly forward-moving urgency are perhaps the right fit for this material, and while I do not, have never, and likely will never love this film, I do admit that it's easy to get swept away by the sheer muchness of it.

*Namely, Ben-Hur in 1959, Titanic in 1997, and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King in 2003)