Skate or die

Screened at the 20th Wisconsin Film Festival.

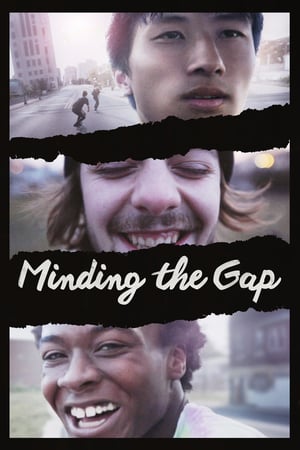

Minding the Gap might be the best coming-of-age movie of the 2010s, in part because it wasn't designed as such, and the subject which comes-of-age isn't necessarily a human adolescent, but the movie itself. The film is the feature debut of director Bing Liu, a young man who taught himself how to make movies as a teenager in the fading post-industrial town of Rockford, Illinois and has since moved on to work in Chicago as a camera assistant. Minding the Gap bridges those two periods in his life (it was finished and released in part through the intercession of Chicago-based A-list documentarian Steve James, who came on as executive producer), though without naming them as such, or ever so much as nodding at Liu's post-Rockford career.

It began, quite obviously and very nearly explicitly, as Liu's high-end home video about him and his buddies at a local skateboard park, and even in this most embryonic, homebrew form, it's clear that he was thinking hard about how to fashion this into a proper movie. The aggressive tracking shots, film by Liu on a skateboard following other people on skateboards, are absolutely stunning, flowing and airy and keenly constrained by the physics of the space where the camera operator was gliding around - watching the image gently pivot on ramps is beautiful, watching it skip over small hills and curbs is terrifying. And in the camera-recorded audio, Liu addresses questions asked by his friends about why the hell he's doing this, making it very clear that he was already plotting out edits in his head (I presume the adolescent Liu would not have included this little snippet, in whatever poetic-Malickian skateboarding doc he had in mind).

Liu, who remains mostly silent and off-camera, but never erases his presence, was clearly driving at making a film about the important psychological solace skateboarding and skate culture offered to several bored and/or troubled young men in Rockford: the conversations which mostly focus on African-American teen Keire and white early-twentysomething Zack, two of the director's closest friends, are all about the empty, and at times violent lives the young men are able to escape in bits and pieces thanks to the skate park. And if that's all the farther that Minding the Gap went, it would already be a fine, if somewhat drab teen memoir, detailing the sociological currents of a segment of the American working class that has been hit hard by the 21st Century (and rarely ever gets so much as a glancing notice in popular culture), as seen through the eyes of young people just barely able to articulate the collapse of the world around them. It's nice enough, and hugely clichéd, but you can tell how much these kids deeply believe in what they're saying.

Anyway, life got in the way of that movie, mostly in the form of Zack getting his girlfriend Nina pregnant. Watching the skateboard crew joke in their idle way about Zack being thrust into responsible adulthood without being ready for it, the clear-headed grown-up viewer cannot help but think the sober, horrified thought "this is not going to go well". And that is just what happens, though in a more protracted and conflicted way than I expected.

This is the point where I shut up about the film's content, just when it's starting to get really interesting: if there is justice of any kind, Minding the Gap is going to keep doing well for itself on the film festival circuit before getting whatever kind of commercial release the small but durable Kartemquin Films is able to manage for it. And when that happens, I want everybody to be able to go into it as blindly as I did (I saw it purely on the recommendation of a friend who's a documentary guy*), because the sudden fluidity of what the film even is, is better experienced than described, I think. Let us suffice to say this: Liu did a lot of growing up over the years of shooting his film, which goes from a simple little piece of adolescent self-promotion to a full-on chronicle of Zack and Keire, with Liu himself drifting in and out, seemingly against his will (in one amazing scene, as he films his mother, it almost feels like showing himself on camera is an act of self-flagellation or expiation for putting her through that). Along the way, he came to recognise awful and cruel things about the kind of world he lived in, and what it does to people, and what people do to each other. The film is a portrayal of the pressures of economic despair, the everyday indignities caused by American society's deep-set racial imbalances, and perhaps most of all, the ugliness of a certain threatened, animalistic masculinity that responds to being most of the way down the social ladder by lashing out at however happens to be all the way down. There's something more sad than angry in Liu's discovery that a man who is great with other men might well be thoroughly awful with women, and how that makes him reflect on his own life, who he has spent it with, and what he is to do going forward.

The film that comes out of all this is a constantly-changing document, from scrapbook to memoir to social-problem essay and back around. Liu has deftly pieced all of this together, silently but clearly indicating the passage of time and the gradual growing-apart of his film's subjects, to that the very act of watching Minding the Gap is itself akin to the psychological process Liu presumably lived through over the course of years: we think we're seeing one thing, we think have this set of human beings figured out, and then we find that we had them all wrong, sometimes in vaguely hopeful ways, sometimes in disappointing and upsetting ways. The arc of the film recreates the act of learning that the world is more complicated and in many ways harsher than you thought, and it does so in a way that remains totally surprising and fresh throughout its running time, even after it becomes clear what the actual film is, once it's no longer a skateboarding movie.

All of this results in a painfully personal, honest presentation of life. I cannot quite bring myself to imagine what Liu had to undergo in order to make the movie that he made, but the results are tremendously rewarding and worthwhile. It's a small, intimate, thing, a portrait of clumsy, messy humanity told with great empathy, but also a clear-eyed lack of sentimentality.

*If you do not have a friend who's a documentary guy, you must get one; they are invaluable.

Minding the Gap might be the best coming-of-age movie of the 2010s, in part because it wasn't designed as such, and the subject which comes-of-age isn't necessarily a human adolescent, but the movie itself. The film is the feature debut of director Bing Liu, a young man who taught himself how to make movies as a teenager in the fading post-industrial town of Rockford, Illinois and has since moved on to work in Chicago as a camera assistant. Minding the Gap bridges those two periods in his life (it was finished and released in part through the intercession of Chicago-based A-list documentarian Steve James, who came on as executive producer), though without naming them as such, or ever so much as nodding at Liu's post-Rockford career.

It began, quite obviously and very nearly explicitly, as Liu's high-end home video about him and his buddies at a local skateboard park, and even in this most embryonic, homebrew form, it's clear that he was thinking hard about how to fashion this into a proper movie. The aggressive tracking shots, film by Liu on a skateboard following other people on skateboards, are absolutely stunning, flowing and airy and keenly constrained by the physics of the space where the camera operator was gliding around - watching the image gently pivot on ramps is beautiful, watching it skip over small hills and curbs is terrifying. And in the camera-recorded audio, Liu addresses questions asked by his friends about why the hell he's doing this, making it very clear that he was already plotting out edits in his head (I presume the adolescent Liu would not have included this little snippet, in whatever poetic-Malickian skateboarding doc he had in mind).

Liu, who remains mostly silent and off-camera, but never erases his presence, was clearly driving at making a film about the important psychological solace skateboarding and skate culture offered to several bored and/or troubled young men in Rockford: the conversations which mostly focus on African-American teen Keire and white early-twentysomething Zack, two of the director's closest friends, are all about the empty, and at times violent lives the young men are able to escape in bits and pieces thanks to the skate park. And if that's all the farther that Minding the Gap went, it would already be a fine, if somewhat drab teen memoir, detailing the sociological currents of a segment of the American working class that has been hit hard by the 21st Century (and rarely ever gets so much as a glancing notice in popular culture), as seen through the eyes of young people just barely able to articulate the collapse of the world around them. It's nice enough, and hugely clichéd, but you can tell how much these kids deeply believe in what they're saying.

Anyway, life got in the way of that movie, mostly in the form of Zack getting his girlfriend Nina pregnant. Watching the skateboard crew joke in their idle way about Zack being thrust into responsible adulthood without being ready for it, the clear-headed grown-up viewer cannot help but think the sober, horrified thought "this is not going to go well". And that is just what happens, though in a more protracted and conflicted way than I expected.

This is the point where I shut up about the film's content, just when it's starting to get really interesting: if there is justice of any kind, Minding the Gap is going to keep doing well for itself on the film festival circuit before getting whatever kind of commercial release the small but durable Kartemquin Films is able to manage for it. And when that happens, I want everybody to be able to go into it as blindly as I did (I saw it purely on the recommendation of a friend who's a documentary guy*), because the sudden fluidity of what the film even is, is better experienced than described, I think. Let us suffice to say this: Liu did a lot of growing up over the years of shooting his film, which goes from a simple little piece of adolescent self-promotion to a full-on chronicle of Zack and Keire, with Liu himself drifting in and out, seemingly against his will (in one amazing scene, as he films his mother, it almost feels like showing himself on camera is an act of self-flagellation or expiation for putting her through that). Along the way, he came to recognise awful and cruel things about the kind of world he lived in, and what it does to people, and what people do to each other. The film is a portrayal of the pressures of economic despair, the everyday indignities caused by American society's deep-set racial imbalances, and perhaps most of all, the ugliness of a certain threatened, animalistic masculinity that responds to being most of the way down the social ladder by lashing out at however happens to be all the way down. There's something more sad than angry in Liu's discovery that a man who is great with other men might well be thoroughly awful with women, and how that makes him reflect on his own life, who he has spent it with, and what he is to do going forward.

The film that comes out of all this is a constantly-changing document, from scrapbook to memoir to social-problem essay and back around. Liu has deftly pieced all of this together, silently but clearly indicating the passage of time and the gradual growing-apart of his film's subjects, to that the very act of watching Minding the Gap is itself akin to the psychological process Liu presumably lived through over the course of years: we think we're seeing one thing, we think have this set of human beings figured out, and then we find that we had them all wrong, sometimes in vaguely hopeful ways, sometimes in disappointing and upsetting ways. The arc of the film recreates the act of learning that the world is more complicated and in many ways harsher than you thought, and it does so in a way that remains totally surprising and fresh throughout its running time, even after it becomes clear what the actual film is, once it's no longer a skateboarding movie.

All of this results in a painfully personal, honest presentation of life. I cannot quite bring myself to imagine what Liu had to undergo in order to make the movie that he made, but the results are tremendously rewarding and worthwhile. It's a small, intimate, thing, a portrait of clumsy, messy humanity told with great empathy, but also a clear-eyed lack of sentimentality.

*If you do not have a friend who's a documentary guy, you must get one; they are invaluable.

Categories: coming-of-age, documentaries