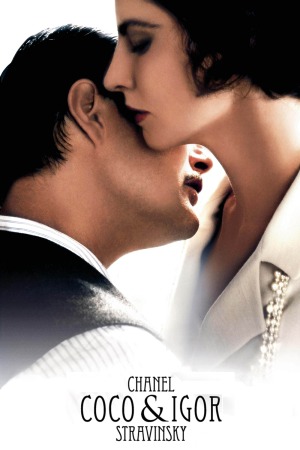

Famous people in love

U.S. theaters aren't going to bear witness this year to a more brazenly functional title than Coco Chanel & Igor Stravinsky, which describes the film's content in fairly absolute terms. The sharp-eyed pedant might point out an even more descriptive title in Coco Chanel & Igor Stravinsky Have a Love Affair, though I maintain that the shorter version is more accurate: the love affair happens, but it is incidental to the film's main thrust, which is to depict Coco Chanel over here, doing this thing, and Igor Stravinsky over there, doing that thing, and they only incidentally come together for some Jazz Age porking. (The historical novel by the film's screenwriter Chris Greenhalgh was briefer still: Coco & Igor).

In 1913, you may know, Stravinsky (played here by Mads Mikkelsen) caused a stir with the premiere of his ferociously dissonant ballet The Rite of Spring for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. Paris itself was burned to the ground in the ensuing riots. But that is not what matters here: it is the film's conceit that the premiere was attended by Gabrielle "Coco" Chanel (Anna Mouglalis), then just a couple of years before her explosive rise to prominence as the 20th Century's most important designer. And moreover, it is the film's conceit that Chanel was one of those who "got" Stravinsky's purpose in creating such an aggressive piece.

Flash forward to 1920: Diaghilev (Grigori Manoukov) introduces the world-renowned Chanel to the still-notorious Stravinsky, floating about Paris with his sick wife, Katarina (Elena Morozova), in tow. Looking to use her wealth and fame for good, Chanel invites him and his family to stay with her in her spacious estate villa outside the city for the summer. There, the designer and the composer fall rather naturally into an affair (this longstanding rumor may or may not be true), the kind of once-in-a-lifetime love (this is a flat-out lie, for both of the individuals in question) that inspires them to greatness: her to create the legendary perfume Chanel No. 5, and him to complete the revisions of Rite of Spring for publication.

One of these things is somewhat less exciting than the other, obviously, and we've come to the first hurdle in appreciating CC ♥ IS, which is that the Chanel half of the story is rich and fascinating - or, at the very least, contains a distinct and recognisable dramatic arc - while the Stravinsky half is... not any of those things. Save for the omnipresence of that composer's music on the film's soundtrack, there's little to no effort made to explain what he did before or after Rite of Spring that was even marginally important. At least Chanel gets to have Big! Dramatic! Moments! in which a great deal of energy is expended so that the audience can have the privilege of seeing something we already knew about coming to fruition, such as the tense moment when she can't decide between the bottles marked"No. 3" and "No. 5" by her perfumist friend, Ernest Beaux (Nicolas Vaude).

All Stravinsky gets to do, in contrast, is sit around and look like he's constantly about to cry, a criminal misuse of Mikkelsen's admirable skills. The film does not present this man with enough character to make him a credible romantic lead - he's barely a credible human being at all. Which means that the film's central conceit deflates rather horribly: "Ah, Coco, you have designed the perfume of a woman deeply in love" we are told, or words to that effect, and all I could think of was Mikkelsen's watery features and lack of affect, then wonder, "Deeply in love with what?"

The good news, though, is that the designer is rather well portrayed, with Mouglalis (an actress not significantly well-known in America) making no effort to mimic or embody Coco Chanel as such (though she looks the part more than cutey-pie Audrey Tatou did in Coco avant Chanel), but instead playing the kind of figure Chanel must have been in her private life, the steely woman who has had to fight against a male-driven society all her professional life and now has little time left over for tenderness or sentiment, and is thus all the more unnerved when tenderness comes of its own accord. It's a strong if not blow-your-mind-open lead performance that is well matched by the story's other dominant female: Morozova's portrayal of Katarina Stravinskaya is a potent if relatively small element of the whole, blending pain, anger, and relief that her husband has at last found some kind of inspiration to resume his work after she grew so sick as to become a burden. This is the best kind of depiction of a stock character (the suffering wife), full of odd little emotional details that make perfect sense but don't conform to the predicted version of the role. Morozova's limited screentime is tremendously haunting, and easily the emotional highlight of the film; not that a movie which risks so much on a desperately flat love story makes that a very high bar to clear.

The good news is that, even if Coco & Igor is only incidentally and by chance a compelling human drama, it's luscious to look at, and I think it's fair to say that the production design and costumes (in that order) are the work's chief raison d'être. Marie-Hélène Sulmoni's magnificent period sets are eye candy of the finest sort, if you like that whole post-WWI design aesthetic (and if you don't, I have to wonder what's wrong with you), captured in pornographic detail by director Jan Kounen and cinematographer David Ungaro (whose collective skills don't honestly seem to extend beyond making the sets and costumes look exquisite, with one exception noted below). The costumes (credited to "Chattoune" and "Fab", and I have no idea what the hell that means, but it excites me) are a bit less thrilling, except for the re-creations of Chanel originals; but come on. Chanel originals.

One other element of the movie absolutely works, though it's still rather porny: the opening Rite of Spring riot, which includes a decent stretch of the ballet itself, in addition to providing the voyeuristic music-history-fetishist thrills of being right there in the Théâtre de Champs-Élysées as one of the most notorious events in 20th Century art happens right there in front of you. If I were advertising the film, I'd really play that part up, using the same gawking "YOU WILL LIVE THE EXCITEMENT" prose used to hawk drive-in movies in the '50s, and if you ever wondered why I am not in film advertising, I think you can no figure it out. But the point stands: this is by far the most carefully-constructed part of the whole movie, cutting around the ballet itself with grand, tension-inducing pacing, and framing the dance with an incredible eye for both detail and the grand scheme. I would have happily stayed put for all 33 minutes of the ballet and none of the wan romantic drama; it may pander to the worst kind of geekery, but that opening sequence still has a vitality and cinematic energy that is almost entirely absent from the rest of the film, a handsome but staid museum piece about nothing very much in particular.

6/10

In 1913, you may know, Stravinsky (played here by Mads Mikkelsen) caused a stir with the premiere of his ferociously dissonant ballet The Rite of Spring for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. Paris itself was burned to the ground in the ensuing riots. But that is not what matters here: it is the film's conceit that the premiere was attended by Gabrielle "Coco" Chanel (Anna Mouglalis), then just a couple of years before her explosive rise to prominence as the 20th Century's most important designer. And moreover, it is the film's conceit that Chanel was one of those who "got" Stravinsky's purpose in creating such an aggressive piece.

Flash forward to 1920: Diaghilev (Grigori Manoukov) introduces the world-renowned Chanel to the still-notorious Stravinsky, floating about Paris with his sick wife, Katarina (Elena Morozova), in tow. Looking to use her wealth and fame for good, Chanel invites him and his family to stay with her in her spacious estate villa outside the city for the summer. There, the designer and the composer fall rather naturally into an affair (this longstanding rumor may or may not be true), the kind of once-in-a-lifetime love (this is a flat-out lie, for both of the individuals in question) that inspires them to greatness: her to create the legendary perfume Chanel No. 5, and him to complete the revisions of Rite of Spring for publication.

One of these things is somewhat less exciting than the other, obviously, and we've come to the first hurdle in appreciating CC ♥ IS, which is that the Chanel half of the story is rich and fascinating - or, at the very least, contains a distinct and recognisable dramatic arc - while the Stravinsky half is... not any of those things. Save for the omnipresence of that composer's music on the film's soundtrack, there's little to no effort made to explain what he did before or after Rite of Spring that was even marginally important. At least Chanel gets to have Big! Dramatic! Moments! in which a great deal of energy is expended so that the audience can have the privilege of seeing something we already knew about coming to fruition, such as the tense moment when she can't decide between the bottles marked"No. 3" and "No. 5" by her perfumist friend, Ernest Beaux (Nicolas Vaude).

All Stravinsky gets to do, in contrast, is sit around and look like he's constantly about to cry, a criminal misuse of Mikkelsen's admirable skills. The film does not present this man with enough character to make him a credible romantic lead - he's barely a credible human being at all. Which means that the film's central conceit deflates rather horribly: "Ah, Coco, you have designed the perfume of a woman deeply in love" we are told, or words to that effect, and all I could think of was Mikkelsen's watery features and lack of affect, then wonder, "Deeply in love with what?"

The good news, though, is that the designer is rather well portrayed, with Mouglalis (an actress not significantly well-known in America) making no effort to mimic or embody Coco Chanel as such (though she looks the part more than cutey-pie Audrey Tatou did in Coco avant Chanel), but instead playing the kind of figure Chanel must have been in her private life, the steely woman who has had to fight against a male-driven society all her professional life and now has little time left over for tenderness or sentiment, and is thus all the more unnerved when tenderness comes of its own accord. It's a strong if not blow-your-mind-open lead performance that is well matched by the story's other dominant female: Morozova's portrayal of Katarina Stravinskaya is a potent if relatively small element of the whole, blending pain, anger, and relief that her husband has at last found some kind of inspiration to resume his work after she grew so sick as to become a burden. This is the best kind of depiction of a stock character (the suffering wife), full of odd little emotional details that make perfect sense but don't conform to the predicted version of the role. Morozova's limited screentime is tremendously haunting, and easily the emotional highlight of the film; not that a movie which risks so much on a desperately flat love story makes that a very high bar to clear.

The good news is that, even if Coco & Igor is only incidentally and by chance a compelling human drama, it's luscious to look at, and I think it's fair to say that the production design and costumes (in that order) are the work's chief raison d'être. Marie-Hélène Sulmoni's magnificent period sets are eye candy of the finest sort, if you like that whole post-WWI design aesthetic (and if you don't, I have to wonder what's wrong with you), captured in pornographic detail by director Jan Kounen and cinematographer David Ungaro (whose collective skills don't honestly seem to extend beyond making the sets and costumes look exquisite, with one exception noted below). The costumes (credited to "Chattoune" and "Fab", and I have no idea what the hell that means, but it excites me) are a bit less thrilling, except for the re-creations of Chanel originals; but come on. Chanel originals.

One other element of the movie absolutely works, though it's still rather porny: the opening Rite of Spring riot, which includes a decent stretch of the ballet itself, in addition to providing the voyeuristic music-history-fetishist thrills of being right there in the Théâtre de Champs-Élysées as one of the most notorious events in 20th Century art happens right there in front of you. If I were advertising the film, I'd really play that part up, using the same gawking "YOU WILL LIVE THE EXCITEMENT" prose used to hawk drive-in movies in the '50s, and if you ever wondered why I am not in film advertising, I think you can no figure it out. But the point stands: this is by far the most carefully-constructed part of the whole movie, cutting around the ballet itself with grand, tension-inducing pacing, and framing the dance with an incredible eye for both detail and the grand scheme. I would have happily stayed put for all 33 minutes of the ballet and none of the wan romantic drama; it may pander to the worst kind of geekery, but that opening sequence still has a vitality and cinematic energy that is almost entirely absent from the rest of the film, a handsome but staid museum piece about nothing very much in particular.

6/10