Universal Horror: You always gill what you love

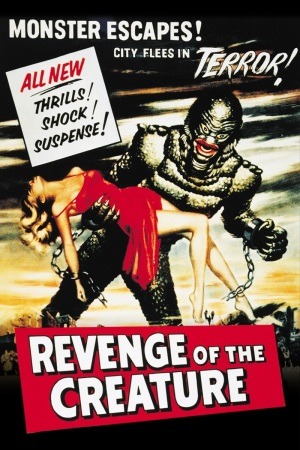

Sequels are always an artistically dubious risk, horror sequels not least of all. It's still hard to process just how much worse 1955's Revenge of the Creature is than its remarkable predecessor. Creature from the Black Lagoon is, if nothing else, one of the truly great B-horror pictures of the 1950s, and with both producer William Alland and director Jack Arnold returning to oversee the sequel, one's natural assumption is that this couldn't be that much worse. Unfortunately, Alland and Arnold were very nearly the only people involved in making the first film to return (makeup & creature designer Bud Westmore and underwater stuntman Ricou Browning are the others worth mentioning), and apparently all the great artistry was hiding with somebody else, because Revenge of the Creature is a dog. There's really just no other way to put it. This is a prime example of the laziest crap in '50s sci-fi and horror, a dismal enough film that it received a prime slot as the first Mystery Science Theater 3000 subject after that series was picked up by the Sci-Fi Channel.

The film does as all good bad sequels do, by retconning the ending of the last one. Remember how the Gill Man (still Browning when he's swimming, with Tom Hennesy taking over on land) sank to the bottom of the Black Lagoon, dead? Well, that's not stopping screenwriter Martin Berkeley, nor the new characters Joe Hayes (John Bromfield) and George Johnson (Robert B. Williams), who've been sent to the Amazon basin from Ocean Harbor, a marine wildlife park in Florida (the film was shot in Marineland, a park outside of Jacksonville). Here, they hope to find the Gill Man and bring him back for study and even more for commercial exploitation. Their guide in this endeavor is none other than good ol' Captain Lucas (Nestor Paiva), who must be South America's biggest glutton for punishment, to sign up for another trip to the Black Lagoon after what happened to him the last time. Naturally enough, since this isn't a five-minute-long movie, the Gill Man is indeed still alive and kicking, and the Floridians rather effortlessly capture him by throwing a whole lot of dynamite into the water and exploding it, stunning the Gill Man and somehow not murdering him in the process.

Back in Florida, Joe attempts to revive the Gill Man, while the whole country watches attentively to see if this primitive throwback has actually survived. One of the most interested of all is Prof. Clete Ferguson (John Agar), an animal behaviorist who has been busily trying to teach chimpanzees how to understand English, while running experiments on taming the natural aggression of predators, in this case one of the most adorably alert housecats you ever did see (the cat test is being monitored by a lab tech named Jennings, who has to suffer through a twee bit of comic relief where he discovers a rat in his pocket. Jennings sucks and nobody would ever care about him, except that he was played by a 24-year-old kid named Clint Eastwood, making his uncredited big-screen acting debut. The camera already loves him and his flinty charisma, but then it's not hard to pull focus when your scene partner is John Agar). The chance to try out his theories on a pseudo-human subject is more than Clete could ever have hoped for, and he's wrangled a chance to lead all the experiments on the Gill Man, much to Joe's consternation - they've known each other in the past, and it is not implied that they were terribly good friends. And just to make things extra fun, there's a woman in between them this time: Helen Dobson (Lori Nelson) an ichthyology master's student from Texas.

The Gill Man revives, anyway - suddenly, of course, the better to almost kill Joe and the other people working with him - and is soon chained to the bottom of a large aquarium, while Clete and Helen teach him to understand the word "stop" by whacking the hell out of him with a cattle prod (now, I don't know much of nothing about cattle prods, but I do have to wonder if holding one while you're underwater isn't a crazy-ass terrible idea). Unsurprisingly, the Gill Man finds this annoying, and so he breaks out, wreaks a little terror, and then grabs Helen from the motel she's staying in, because being horny as hell for blondes in white one-pieces is what Gill Men do best.

Oh, but I've skipped ahead. I've skipped ahead a whole lot. At 81 minutes, Revenge of the Creature is the longest film in the Gill Man trilogy (by a whopping two minutes, but still), and it is time horribly wasted. The great majority of the film consists of watching the Gill Man paddling about in his tiny new home, and watching the scientists poke at him, and watching the love triangle almost immediately extinguish itself, because Agar was a much bigger star than Bromfield could even imagine being. What the hell Joe is even doing in the movie is anybody's guess; he's plainly only there to facilitate this nonexistent love triangle, with every other one of his plot functions easily replaced by Clete.

Regardless, Joe is on-hand to do much the same as every other human in the movie: waste time. It's impossible to overstate how utterly tedious the central stretch of Revenge of the Creature is, with Agar occasionally making some enormously serious pronouncement about the Gill Man's behavior or physiology or whatever. This is, I want to make clear, completely useless. We in the audience don't care about what the Gill Man is or why he does what he does; Gill Men don't exist. They are movie creations, and we only want to see him be a movie monster, not be the subject of boring actors playing make-believe researchers. It is all too stultifying, and that's not even including the actual worst part, which is the amount of footage that's literally just the aquariums. For what feel like tens of minutes, though I'm sure it's more like 30 seconds, the film grinds to a halt to stop and watch the fish. I suspect that the viewer of Revenge of the Creature spends more time looking at Marineland's exhibits than actual visitors to Marineland did. This movie, like Creature from the Black Lagoon, was initially shot in 3-D (it was, in fact, the last 3-D film released in the 1950s), and while my memories of the single time I saw in that format are not strong, I remember it being mostly just an excuse to watch fish in all kinds of dimensions - fish near, fish far, fish right up in your face. Certainly, there's none of the evocative, involving storytelling in three dimensions that there was in the previous film. Arnold's heart didn't appear to be in it.

Arnold's heart didn't appear to be in anything. An invested director wouldn't let a monster movie stumble and crawl along for such a profoundly long period of time with such a very tiny amount of incident happening. An invested director would probably also work to get better performances out of his cast. I mean, Agar was never a great actor on his very best day, but he had a level of confident competence that was generally quite satisfactory in a B-movie leading man, and here's he's just a smug prick of absolutely no distinction. Nelson is stuck in the usual thankless role as the woman scientist that all the other characters treat in the most patronising way (and the movie joins in, with a weirdly proto-feminist scene about how sad it is that smart woman can't get the credit they deserve; but hey, at least you're pretty!), and doesn't have anything like the skill, presence, or inclination to fight against it.

Then again, even a very invested director probably wouldn't stay invested very long when faced with the cringingly unimaginative scenario presented here. It's a transparent and self-conscious King Kong knock-off done in by a huge dose of '50s movie science and terrible effects. Oh my, how terrible! It's incredibly galling, just a year after the first Gill Man suit, to see the shabby piece of shit that filmmakers were able to come up with this time: the pulsing gills are a neat addition, but the rest of it just looks cheap as all hell. The texturing is off; the suit has been painted a much darker color that makes it look exactly like rubber in black and white. And that's not even mentioning the obviously artificial head, with its giant bug eyes and what looks for all the world like a one-inch snorkel on the back; at any rate, it's prone to dispensing bubbles in a neat little straight line, like absolutely nothing in the natural world, and there are plenty of shots where it's very much in focus.

The whole thing, in other words, is an obvious cash-grab, striking while the iron is still hot and people still had fond memories of the first one. The resultant film simply reeks of disinterest in every way, from its slack pacing to its crappy monster, to its boring pro forma chase climax, to its ugly cinematography of Florida. Florida! There might not be a better way to sum up the film's shortcomings than that: to switch the action from the misty adventureland of the Amazon to the middle of the ugliest damn swath of land in the United States, northern Florida.

Reviews in this series

Creature from the Black Lagoon (Arnold, 1954)

Revenge of the Creature (Arnold, 1955)

The Creature Walks Among Us (Sherwood, 1956)

The film does as all good bad sequels do, by retconning the ending of the last one. Remember how the Gill Man (still Browning when he's swimming, with Tom Hennesy taking over on land) sank to the bottom of the Black Lagoon, dead? Well, that's not stopping screenwriter Martin Berkeley, nor the new characters Joe Hayes (John Bromfield) and George Johnson (Robert B. Williams), who've been sent to the Amazon basin from Ocean Harbor, a marine wildlife park in Florida (the film was shot in Marineland, a park outside of Jacksonville). Here, they hope to find the Gill Man and bring him back for study and even more for commercial exploitation. Their guide in this endeavor is none other than good ol' Captain Lucas (Nestor Paiva), who must be South America's biggest glutton for punishment, to sign up for another trip to the Black Lagoon after what happened to him the last time. Naturally enough, since this isn't a five-minute-long movie, the Gill Man is indeed still alive and kicking, and the Floridians rather effortlessly capture him by throwing a whole lot of dynamite into the water and exploding it, stunning the Gill Man and somehow not murdering him in the process.

Back in Florida, Joe attempts to revive the Gill Man, while the whole country watches attentively to see if this primitive throwback has actually survived. One of the most interested of all is Prof. Clete Ferguson (John Agar), an animal behaviorist who has been busily trying to teach chimpanzees how to understand English, while running experiments on taming the natural aggression of predators, in this case one of the most adorably alert housecats you ever did see (the cat test is being monitored by a lab tech named Jennings, who has to suffer through a twee bit of comic relief where he discovers a rat in his pocket. Jennings sucks and nobody would ever care about him, except that he was played by a 24-year-old kid named Clint Eastwood, making his uncredited big-screen acting debut. The camera already loves him and his flinty charisma, but then it's not hard to pull focus when your scene partner is John Agar). The chance to try out his theories on a pseudo-human subject is more than Clete could ever have hoped for, and he's wrangled a chance to lead all the experiments on the Gill Man, much to Joe's consternation - they've known each other in the past, and it is not implied that they were terribly good friends. And just to make things extra fun, there's a woman in between them this time: Helen Dobson (Lori Nelson) an ichthyology master's student from Texas.

The Gill Man revives, anyway - suddenly, of course, the better to almost kill Joe and the other people working with him - and is soon chained to the bottom of a large aquarium, while Clete and Helen teach him to understand the word "stop" by whacking the hell out of him with a cattle prod (now, I don't know much of nothing about cattle prods, but I do have to wonder if holding one while you're underwater isn't a crazy-ass terrible idea). Unsurprisingly, the Gill Man finds this annoying, and so he breaks out, wreaks a little terror, and then grabs Helen from the motel she's staying in, because being horny as hell for blondes in white one-pieces is what Gill Men do best.

Oh, but I've skipped ahead. I've skipped ahead a whole lot. At 81 minutes, Revenge of the Creature is the longest film in the Gill Man trilogy (by a whopping two minutes, but still), and it is time horribly wasted. The great majority of the film consists of watching the Gill Man paddling about in his tiny new home, and watching the scientists poke at him, and watching the love triangle almost immediately extinguish itself, because Agar was a much bigger star than Bromfield could even imagine being. What the hell Joe is even doing in the movie is anybody's guess; he's plainly only there to facilitate this nonexistent love triangle, with every other one of his plot functions easily replaced by Clete.

Regardless, Joe is on-hand to do much the same as every other human in the movie: waste time. It's impossible to overstate how utterly tedious the central stretch of Revenge of the Creature is, with Agar occasionally making some enormously serious pronouncement about the Gill Man's behavior or physiology or whatever. This is, I want to make clear, completely useless. We in the audience don't care about what the Gill Man is or why he does what he does; Gill Men don't exist. They are movie creations, and we only want to see him be a movie monster, not be the subject of boring actors playing make-believe researchers. It is all too stultifying, and that's not even including the actual worst part, which is the amount of footage that's literally just the aquariums. For what feel like tens of minutes, though I'm sure it's more like 30 seconds, the film grinds to a halt to stop and watch the fish. I suspect that the viewer of Revenge of the Creature spends more time looking at Marineland's exhibits than actual visitors to Marineland did. This movie, like Creature from the Black Lagoon, was initially shot in 3-D (it was, in fact, the last 3-D film released in the 1950s), and while my memories of the single time I saw in that format are not strong, I remember it being mostly just an excuse to watch fish in all kinds of dimensions - fish near, fish far, fish right up in your face. Certainly, there's none of the evocative, involving storytelling in three dimensions that there was in the previous film. Arnold's heart didn't appear to be in it.

Arnold's heart didn't appear to be in anything. An invested director wouldn't let a monster movie stumble and crawl along for such a profoundly long period of time with such a very tiny amount of incident happening. An invested director would probably also work to get better performances out of his cast. I mean, Agar was never a great actor on his very best day, but he had a level of confident competence that was generally quite satisfactory in a B-movie leading man, and here's he's just a smug prick of absolutely no distinction. Nelson is stuck in the usual thankless role as the woman scientist that all the other characters treat in the most patronising way (and the movie joins in, with a weirdly proto-feminist scene about how sad it is that smart woman can't get the credit they deserve; but hey, at least you're pretty!), and doesn't have anything like the skill, presence, or inclination to fight against it.

Then again, even a very invested director probably wouldn't stay invested very long when faced with the cringingly unimaginative scenario presented here. It's a transparent and self-conscious King Kong knock-off done in by a huge dose of '50s movie science and terrible effects. Oh my, how terrible! It's incredibly galling, just a year after the first Gill Man suit, to see the shabby piece of shit that filmmakers were able to come up with this time: the pulsing gills are a neat addition, but the rest of it just looks cheap as all hell. The texturing is off; the suit has been painted a much darker color that makes it look exactly like rubber in black and white. And that's not even mentioning the obviously artificial head, with its giant bug eyes and what looks for all the world like a one-inch snorkel on the back; at any rate, it's prone to dispensing bubbles in a neat little straight line, like absolutely nothing in the natural world, and there are plenty of shots where it's very much in focus.

The whole thing, in other words, is an obvious cash-grab, striking while the iron is still hot and people still had fond memories of the first one. The resultant film simply reeks of disinterest in every way, from its slack pacing to its crappy monster, to its boring pro forma chase climax, to its ugly cinematography of Florida. Florida! There might not be a better way to sum up the film's shortcomings than that: to switch the action from the misty adventureland of the Amazon to the middle of the ugliest damn swath of land in the United States, northern Florida.

Reviews in this series

Creature from the Black Lagoon (Arnold, 1954)

Revenge of the Creature (Arnold, 1955)

The Creature Walks Among Us (Sherwood, 1956)