Blockbuster History: Talking animals

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: the deeply unwarranted sequel Cats and Dogs: The Revenge of Kitty Galore finds the hideous trend of live-action movies with awful CGI talking beasts is no closer to its necessary death than ever; but let's not blame the award-winning film that got this ball rolling for the inexcusable sins of its descendants.

If there is one sentiment that I could strike from all discussion of cinema (and art generally, but let's not go overboard), it would probably be the insidious and pervasive notion that movies produced largely for a young audience ought to be judged on a curve. "Whatever, it's a kids' movie." "God, why are you nitpicking? It's a kids' movie." "Not very good, but the kids will like it."

Fuck. That. Noise.

If anything, we should hold children's entertainment to the highest standard, not the lowest. They're the ones who still have all their guilelessness and innocence intact; they who are still shaping and forming their concept of the world in all its wonder and splendor and pain and misery; they whose empty minds suck up every detail like a sponge. Show an adult a shitty movie, and it's forgotten by dinnertime; show a kid a shitty movie, and you have put a constraint on their world. A steady diet of substandard factory-produced pap, leads only to a generation of children unable to respond to movies as anything but product (AKA "the last two generations of filmgoers"). Which is why I despise most modern-day family movies: all they do is raise kids up to be tomorrow's eager ticket-buyers for Transpirates vs. Spider-Bat.

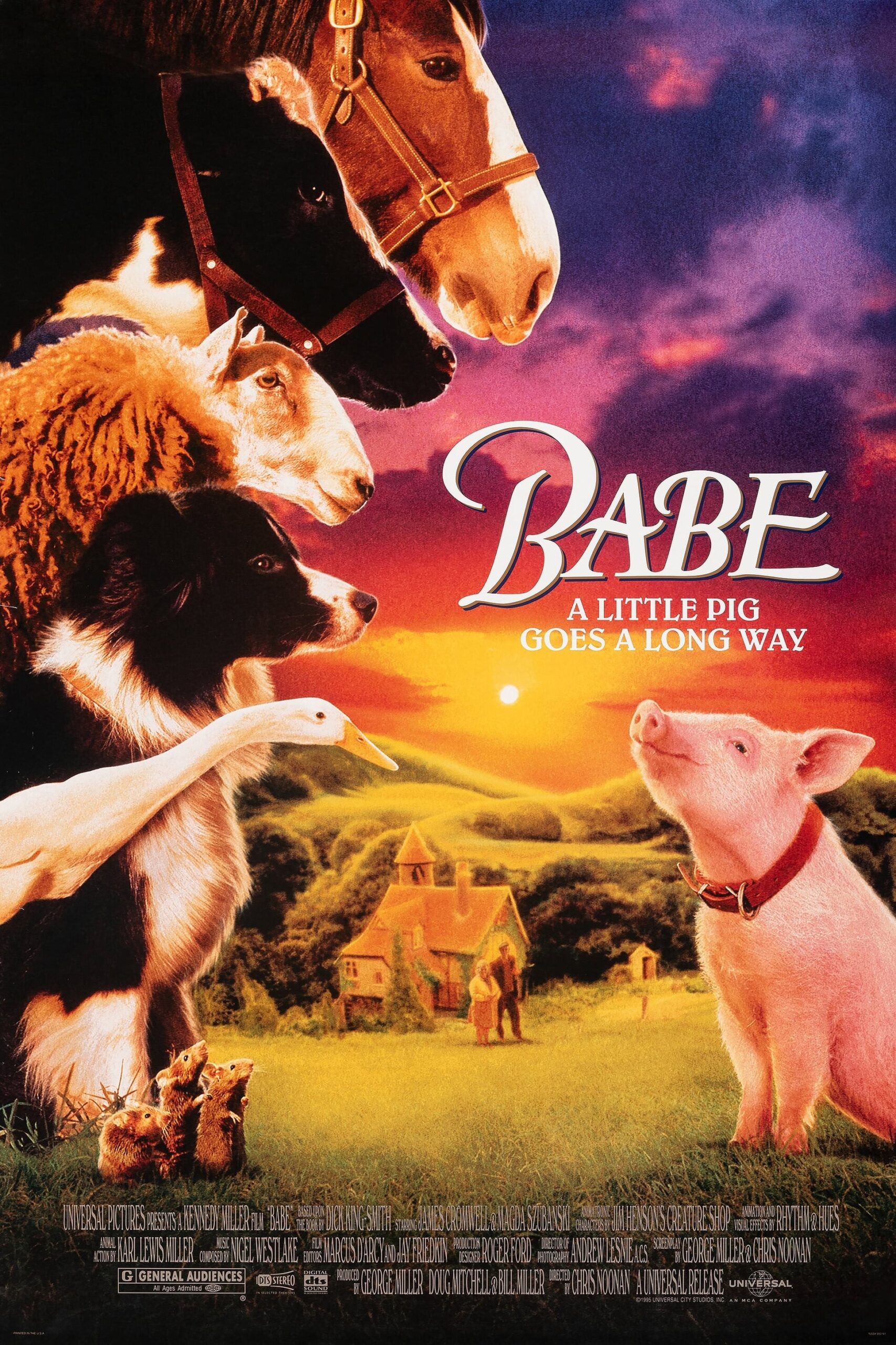

Still, one sneaks out every now and then, and in the last 20 years, I'd be hard-pressed to name a single kids' movie - though that very phrase, "kids' movie", is an unfair and unjust ghettoisation - that triumphs more completely on more levels than Babe, a 1995 Australian film co-written by the director of the Mad Max franchise, and directed by a man who'd never directed a feature before, and wouldn't direct again for eleven years (breaking his drought with Miss Potter, of all things, but let's not go there). Babe is a masterpiece; there is no lesser word that fits it so well. Every movie for children should be made with this much care, expressing this much unparalleled richness and beauty; great enough even the milquetoast Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences was compelled to hand the very awards-unfriendly film an Oscar nomination for Best Picture (and six others besides!) - as of this writing, the last G-rated Best Picture nominee (in, coincidentally, the only year between 1984 and 2004 with but a single R-rated nominee).

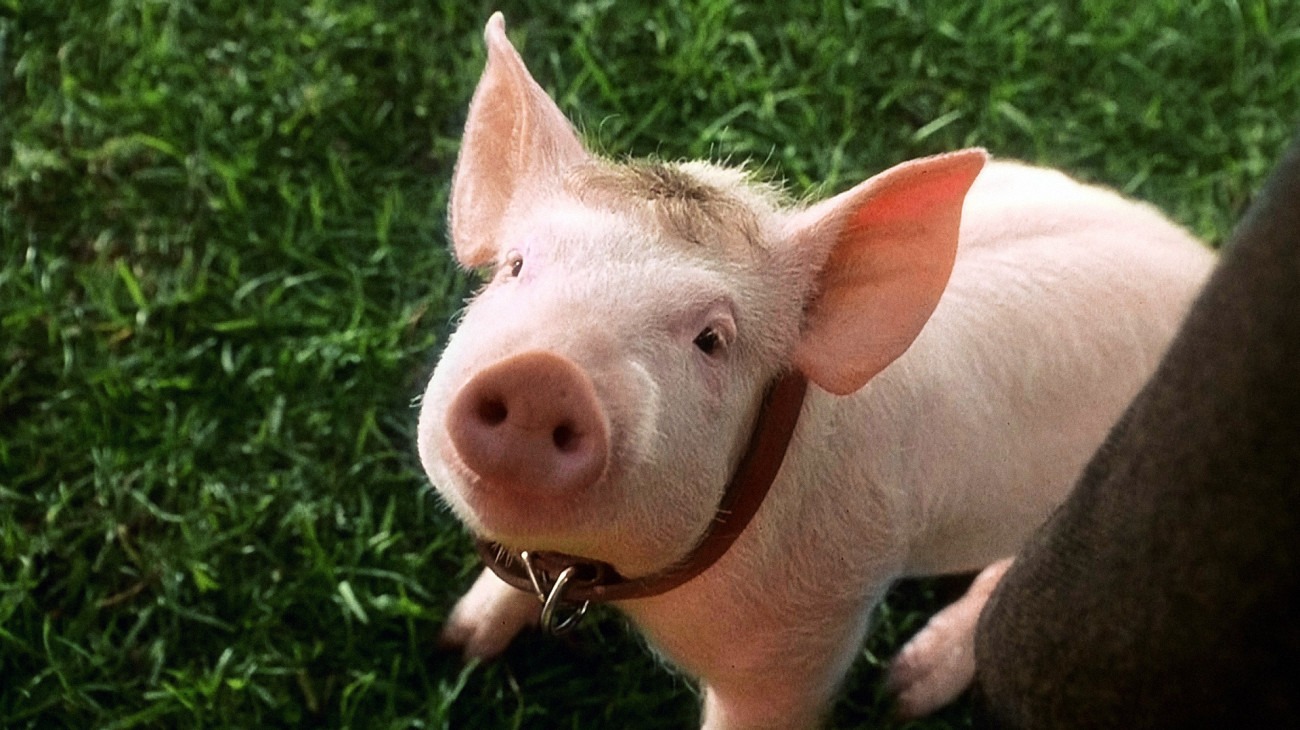

The story, told over an unrushed 92 minutes, is slight as slight can be: a piglet (voiced by Christine Cavanaugh) is won by a sheep farmer (James Cromwell), taken in by the farmer's dogs, and sets himself to herding sheep. Anything else is just adornment, though very lovely adornment, and perfectly necessary. As with any fairy tale - and by all means, Babe is nothing if not a fairy tale - it's the details that make it truly special. For it in the details that the Hoggett farm, nestled in a quiet corner of the Australian countryside, blossoms into a tiny microcosm of all humanity as rich as the Pequod of Moby-Dick or Elsinore in Hamlet. Love and anger, innocence and cynicism, and the hoariest binary of them all, life and death; all are explored in Babe with a feather touch that could deceive you into thinking that you're just watching a nice, simple little bit of fluff. And even as fluff, it's surpassing wonderful: an intoxicating blend of sharply-etched characters, four- and two-legged, witty and sweet.

And yet, fluff it is not: Babe has a profundity that can only be attained by art that outwardly eschews profundity - there's something uncanny in the way that the two most sincere and emotionally rewarding English-language films of 1995 were both ostensibly kids' movies (the other being the original Toy Story). The message is simple: don't listen when other people try to hold you back by saying "that's not the way things are," because "the way things are" usually can do with a change. The vehicle is simple: the inexplicable and very real feeling of mutual understanding that can crop up between an animal and a human being. Babe, by all means, ought to be simple - but there's nothing simple about a movie that can send you from one emotional high to another, just by means of some animatronic pigs and dogs and Cromwell's studied, taciturn performance as Arthur Hoggett. And, of course, the judicious application of Camille Saint-Saëns's soaring Symphonie No. 3 as the most unexpected leitmotif in the history of children's entertainment.

How is this kind of glorious affect carried out? I've been trying to puzzle that one out for 15 years, and I'm still no closer to an answer. Babe is a great work of cinematic craftsmanship, of course: with Roger Ford's outstanding production design and Colin Gibson's art direction creating an over-stuffed world of visual details, and Andrew Lesnie, in his best moment by far as a cinematographer, framing and lighting the movie with a golden glow that gives it the idyllic feel of a postcard, with some of the shots rising to level of sheer poetry (as in the case of a sunset that draws a visual comparison between fluffy clouds and piles of fleece). Director Chris Noonan treats the whole thing as both magical and utterly workaday in perfect harmony - when the narrator (Roscoe Lee Brown) intones that a certain day begins just like any other at the Hoggett farm, it doesn't even register that it's only, technically, the second day we've witnessed at the farm, so thoroughly have we been swept into the world.

But the creation of a completely entrancing mise en scène isn't the only answer, though of course the fairy tale element that gives Babe so much of its casual potency (nothing is ever more powerful than a fairy tale when you're in a receptive mood) relies in large part upon the perfection of the Hoggett farm, especially as it's contrasted with the grim blackness of the pig factory where Babe is born and first begins to question "the way things are" with a heartbreakingly subdued "good-bye, Mom" as his mother is taken to "Pig Heaven". The structure of the plot has something to do with it; adapted by Noonan and producer George "I invented the post-apocalypse epic" Miller, Babe is divided into segments, each given a title, helpfully read by the farm's chattering, easily-excited mice. This gives the narrative an episodic structure that actually doesn't fit; save for one mostly-superfluous swerve into the story of how Babe helps Ferdinand the duck (Danny Mann) steal the Hoggetts' alarm clock, every moment in the story bleeds into the next, and the earlier sequences all set up a point that will be paid off later. But the division, while somewhat artificial, lends the movie even more of that storybook tone than the storybook-illustration visuals do.

Beyond that, there is the all-important matter of the performances: Cromwell's stiff Hoggett, whose pragmatic, nearly-silent shell hides the heart of a fantasist and a romantic that only barely peeks out in the course of the movie, is a masterpiece of restrained acting, great enough to unfairly overshadowed Magda Szubanski's lovely turn as Mrs. Hoggett, a perfect comic creation who's all reactions and amazed dismay, but never feels stupid or silly. But the best performances are all in the animals: not just the voice-actors (including Hugo Weaving and Miriam Margolyes, for a start), but the physical representation carried off by a sublime combination of well-trained animals, otherworldly Jim Henson's Creature Shop puppets, and just a dash of CGI from Rhythm & Hues. There has never been and I suppose never will be another talking-animals movie where that effect looks so utterly unforced as Babe; the non-human characters express exactly the emotions that they're meant to, without seeming cloyingly anthropomorphic, and more importantly, never ever seem faked. At this point, I must throw up my hands and confess that I don't know how they made that happen. It just works, possessed of an X-factor that beggars analysis.

I have still, all these words later, not explained why Babe is so dear and powerful and moving; and ultimately, I don't think I can. It stares your grown-up rationalism in the face and demolishes it with its implacable gaze; it requires an unabashed openness - one might say, a willful naïveté - and rewards it tenfold. Visually, aurally, and as a bedtime story for anyone of any age who needs to feel better about the world, Babe is entirely beautiful, from the scariness of the opening through the humor and melancholy of the characters and plot, up to the last snatch of dialogue and the final shots, a quiet contemplation on how solitary beings connect with one another, and create meaning in the lives of others through simple acts of grace. It is a work of the sublimest tenderness and sincerity, the rare kind of film that truly believes that we all have it in us to make the world a better place.

If there is one sentiment that I could strike from all discussion of cinema (and art generally, but let's not go overboard), it would probably be the insidious and pervasive notion that movies produced largely for a young audience ought to be judged on a curve. "Whatever, it's a kids' movie." "God, why are you nitpicking? It's a kids' movie." "Not very good, but the kids will like it."

Fuck. That. Noise.

If anything, we should hold children's entertainment to the highest standard, not the lowest. They're the ones who still have all their guilelessness and innocence intact; they who are still shaping and forming their concept of the world in all its wonder and splendor and pain and misery; they whose empty minds suck up every detail like a sponge. Show an adult a shitty movie, and it's forgotten by dinnertime; show a kid a shitty movie, and you have put a constraint on their world. A steady diet of substandard factory-produced pap, leads only to a generation of children unable to respond to movies as anything but product (AKA "the last two generations of filmgoers"). Which is why I despise most modern-day family movies: all they do is raise kids up to be tomorrow's eager ticket-buyers for Transpirates vs. Spider-Bat.

Still, one sneaks out every now and then, and in the last 20 years, I'd be hard-pressed to name a single kids' movie - though that very phrase, "kids' movie", is an unfair and unjust ghettoisation - that triumphs more completely on more levels than Babe, a 1995 Australian film co-written by the director of the Mad Max franchise, and directed by a man who'd never directed a feature before, and wouldn't direct again for eleven years (breaking his drought with Miss Potter, of all things, but let's not go there). Babe is a masterpiece; there is no lesser word that fits it so well. Every movie for children should be made with this much care, expressing this much unparalleled richness and beauty; great enough even the milquetoast Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences was compelled to hand the very awards-unfriendly film an Oscar nomination for Best Picture (and six others besides!) - as of this writing, the last G-rated Best Picture nominee (in, coincidentally, the only year between 1984 and 2004 with but a single R-rated nominee).

The story, told over an unrushed 92 minutes, is slight as slight can be: a piglet (voiced by Christine Cavanaugh) is won by a sheep farmer (James Cromwell), taken in by the farmer's dogs, and sets himself to herding sheep. Anything else is just adornment, though very lovely adornment, and perfectly necessary. As with any fairy tale - and by all means, Babe is nothing if not a fairy tale - it's the details that make it truly special. For it in the details that the Hoggett farm, nestled in a quiet corner of the Australian countryside, blossoms into a tiny microcosm of all humanity as rich as the Pequod of Moby-Dick or Elsinore in Hamlet. Love and anger, innocence and cynicism, and the hoariest binary of them all, life and death; all are explored in Babe with a feather touch that could deceive you into thinking that you're just watching a nice, simple little bit of fluff. And even as fluff, it's surpassing wonderful: an intoxicating blend of sharply-etched characters, four- and two-legged, witty and sweet.

And yet, fluff it is not: Babe has a profundity that can only be attained by art that outwardly eschews profundity - there's something uncanny in the way that the two most sincere and emotionally rewarding English-language films of 1995 were both ostensibly kids' movies (the other being the original Toy Story). The message is simple: don't listen when other people try to hold you back by saying "that's not the way things are," because "the way things are" usually can do with a change. The vehicle is simple: the inexplicable and very real feeling of mutual understanding that can crop up between an animal and a human being. Babe, by all means, ought to be simple - but there's nothing simple about a movie that can send you from one emotional high to another, just by means of some animatronic pigs and dogs and Cromwell's studied, taciturn performance as Arthur Hoggett. And, of course, the judicious application of Camille Saint-Saëns's soaring Symphonie No. 3 as the most unexpected leitmotif in the history of children's entertainment.

How is this kind of glorious affect carried out? I've been trying to puzzle that one out for 15 years, and I'm still no closer to an answer. Babe is a great work of cinematic craftsmanship, of course: with Roger Ford's outstanding production design and Colin Gibson's art direction creating an over-stuffed world of visual details, and Andrew Lesnie, in his best moment by far as a cinematographer, framing and lighting the movie with a golden glow that gives it the idyllic feel of a postcard, with some of the shots rising to level of sheer poetry (as in the case of a sunset that draws a visual comparison between fluffy clouds and piles of fleece). Director Chris Noonan treats the whole thing as both magical and utterly workaday in perfect harmony - when the narrator (Roscoe Lee Brown) intones that a certain day begins just like any other at the Hoggett farm, it doesn't even register that it's only, technically, the second day we've witnessed at the farm, so thoroughly have we been swept into the world.

But the creation of a completely entrancing mise en scène isn't the only answer, though of course the fairy tale element that gives Babe so much of its casual potency (nothing is ever more powerful than a fairy tale when you're in a receptive mood) relies in large part upon the perfection of the Hoggett farm, especially as it's contrasted with the grim blackness of the pig factory where Babe is born and first begins to question "the way things are" with a heartbreakingly subdued "good-bye, Mom" as his mother is taken to "Pig Heaven". The structure of the plot has something to do with it; adapted by Noonan and producer George "I invented the post-apocalypse epic" Miller, Babe is divided into segments, each given a title, helpfully read by the farm's chattering, easily-excited mice. This gives the narrative an episodic structure that actually doesn't fit; save for one mostly-superfluous swerve into the story of how Babe helps Ferdinand the duck (Danny Mann) steal the Hoggetts' alarm clock, every moment in the story bleeds into the next, and the earlier sequences all set up a point that will be paid off later. But the division, while somewhat artificial, lends the movie even more of that storybook tone than the storybook-illustration visuals do.

Beyond that, there is the all-important matter of the performances: Cromwell's stiff Hoggett, whose pragmatic, nearly-silent shell hides the heart of a fantasist and a romantic that only barely peeks out in the course of the movie, is a masterpiece of restrained acting, great enough to unfairly overshadowed Magda Szubanski's lovely turn as Mrs. Hoggett, a perfect comic creation who's all reactions and amazed dismay, but never feels stupid or silly. But the best performances are all in the animals: not just the voice-actors (including Hugo Weaving and Miriam Margolyes, for a start), but the physical representation carried off by a sublime combination of well-trained animals, otherworldly Jim Henson's Creature Shop puppets, and just a dash of CGI from Rhythm & Hues. There has never been and I suppose never will be another talking-animals movie where that effect looks so utterly unforced as Babe; the non-human characters express exactly the emotions that they're meant to, without seeming cloyingly anthropomorphic, and more importantly, never ever seem faked. At this point, I must throw up my hands and confess that I don't know how they made that happen. It just works, possessed of an X-factor that beggars analysis.

I have still, all these words later, not explained why Babe is so dear and powerful and moving; and ultimately, I don't think I can. It stares your grown-up rationalism in the face and demolishes it with its implacable gaze; it requires an unabashed openness - one might say, a willful naïveté - and rewards it tenfold. Visually, aurally, and as a bedtime story for anyone of any age who needs to feel better about the world, Babe is entirely beautiful, from the scariness of the opening through the humor and melancholy of the characters and plot, up to the last snatch of dialogue and the final shots, a quiet contemplation on how solitary beings connect with one another, and create meaning in the lives of others through simple acts of grace. It is a work of the sublimest tenderness and sincerity, the rare kind of film that truly believes that we all have it in us to make the world a better place.