Who ya gonna call?

The blog has been on a bit of an '80s kick lately, and Adam Bertocci did his part to keep things going when he donated to the Carry On Campaign and requested today's review. Three cheers for the decade of Reagan, leg warmers,and hair metal!

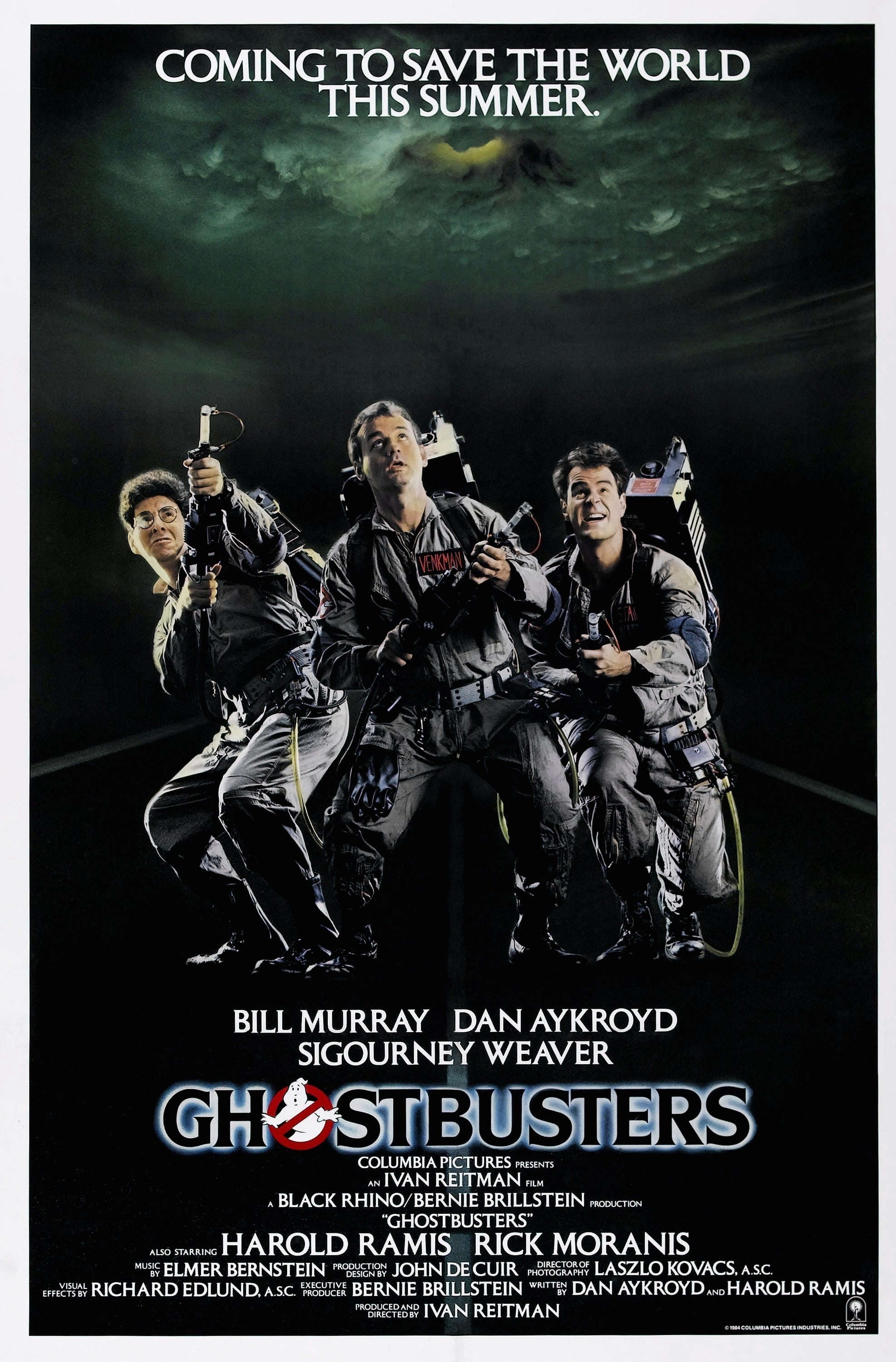

Even for a decade in which the high-concept comedy reached its apex, there's something exceptionally high-concept about Ghostbusters: a horror and science-fiction hybrid whose state-of-the-art visual effects were so damn state-of-the art that the film still wasn't quite finished when it premiered in June, 1984, and yet at heart it's just a buddy comedy, just a tale of the geek and the wiseacre like a number of significantly less costly films from the same period.

Of course, given that we hardly recall most of those other movies even with the haze of nostalgia, while Ghostbusters remains as iconic a pop culture touchstone as any other movie from that decade (I can wax all the rhapsodic I want to over The Princess Bride, for example, but must always finally acknowledge that nobody - or only a teeny number of people - would be breathlessly excited for a first-person Princess Bride video game in this day and age), I don't mean to suggest that its big-budget somehow makes it a shallower thing: the very reason for its longevity has everything to do with its "bigness", its costly high-concept ambition which lends the film a kind of grandeur and impressiveness that sets off its resolutely intimate, human-sized comedy and makes it seem all the funnier for the contrast (a similar dynamic drives Men in Black, which has long struck me as the last of the great '80s action-comedies, stranded out in the back half of the 1990s).

For, taken strictly as a comedy and nothing else, Ghostbusters has a very definite loose and ultra-casual feel to it, born of the low-key genial good humor typical of writers Dan Aykroyd and Harold Ramis in those days, and carried further still by a clutch of lead performances that seem to have the shrugged-off sense of improvisation (the top-billed star, a certain Bill Murray, may indeed have improvised a great deal of his work, although how much varies depending on the source you follow). It's not hard to see the creators' background in projects like The Blues Brothers and Caddyshack shining through: movies that are very much in a chilled-out, "we're all just hanging around, being goofy" sort of mood.

Indeed, so casual and cool is the movie, it's altogether shaggy- but just in case, I should quickly outline the plot, I suppose. Three parapsychology professors in New York, Drs. Peter Venkman (Murray), Ray Stantz (Aykroyd) and Egon Spengler (Ramis), are given the boot when their school determines that they're layabouts spending too much money on go-nowhere research. And we have every reason to side with the school, given that the first we see of these gentlemen is Venkman rigging an ESP test to favor a pretty girl that he'd self-evidently like to screw. Deprived of income and a place to conduct Stantz and Spengler's experiments on ghostly phenomenon, the trio manage to set themselves up as New York's only paranormal exterminators, and in just a little while they've proven themselves both as scientists and as public servants. Just in time, too, for the recent uptick in ghost activity in the city is tied to a forgotten Sumerian god called "Gozer" - and whatever Gozer is, it has a particular interest in Dana Barrett (Sigourney Weaver), a musician whom Venkman has been courting, mostly without success.

Now then, that shagginess: the plot of the film is the investigation into stopping Gozer's return, and the movie is well aware of it. But everything that gets us to that point is slapped together; frankly, Ghostbusters has a broken first act, in which we are introduced to our three characters and their paranormal interests, shown the creation of their science and their company, introduced to their snippy receptionist, Janine Melnitz (Annie Potts, a dismally under-used actress whom I have loved since before I can remember - any other fans of the long-extinct sitcom Love & War out there?), and their new recruit, Winston Zeddmore (Ernie Hudson), and given quite a few scoops of foreshadowing, and all of it done so lazily that it would get a failing grade in any screenwriting class in the world. A great deal of information is simply posited, and we damn well better be okay with it; details are thrown out that seem to tie back in to nothing at all (one example from a sea of them: with the money gained from a third mortgage on a single-family home, the boys are able to finance what must be hundreds of thousands of dollars of equipment); arguably the most interesting part of the whole narrative, the ghostbusters' rise from crackpots to national celebrities, is covered in a montage set to Ray Parker's inescapable "Ghostbusters" theme song.

This is not one of those insights that grabbed me as I discovered a beloved slice of childhood to be a shell of what I remembered. Unlike a lot of films that I wore out on VHS, I've seen Ghostbusters frequently - prior to re-watching it for this review, it couldn't have been even two years since I saw it last. And here's the important thing: prior to re-watching it for review, I had never thought about the first act as being dysfunctional in any way. And that's why I have chosen to call it "shaggy": it's unkempt and messy and doesn't really work, except it really works. Which brings us back to the loosey-goosey casualness, and the irremovable anchor brought to the film by the Murray-Aykroyd-Ramis triumvirate.

(Incidentally, I feel terrible for Hudson: it must be thankless than playing the fourth man in a three-man show, though it wasn't always meant to be. In the early stages, his role was intended to be longer, a vehicle for Eddie Murphy, who turned it down in favor of Beverly Hills Cop. A good thing, too: the slacker-ish, buddy-movie vibe would have been seriously damaged by a more prominent role for Zeddmore, especially one with Murphy's generally more manic persona. And the jockeying for prominence between him and Murray would have been intolerable, although it's equally likely that another actor would have been cast as Venkman in this scenario).

Whether by design, accident, or after-the-fact stroke of genius in the editing room, Ghostbusters is Bill Murray's movie. Without Aykroyd and Ramis to bounce his sardonic delivery off of, it's true that there'd be nothing for him to do; but without his performance, in which he forever crystallised his persona as a sarcastic & weary, but oddly likable smart-ass, the simultaneously breezy and snotty mood of the movie simply would not exist. It's hard to believe until you start looking for it, how much of Ghostbusters consists of nothing but Murray's reactions to things: to Ramis's deadpan technobabble, to William Atherton's prissy EPA inspector, to Weaver's prickly charm (incidentally, with the intensely wonderful chemistry between Murray and Weaver on display here, I consider it nothing shy of a crime that they never made a movie together outside of this franchise). Not to diminish the other actors' contributions: Aykroyd in particular has some entirely marvelous lines and moments, and Rick Moranis's smallish role as the twerpy accountant Louis Tully is a tiny comic gem, albeit one that largely exists in some totally different movie. I just feel, steadfastly, that it is Murray who sets the comic tone, and the other performers simply follow in his wake.

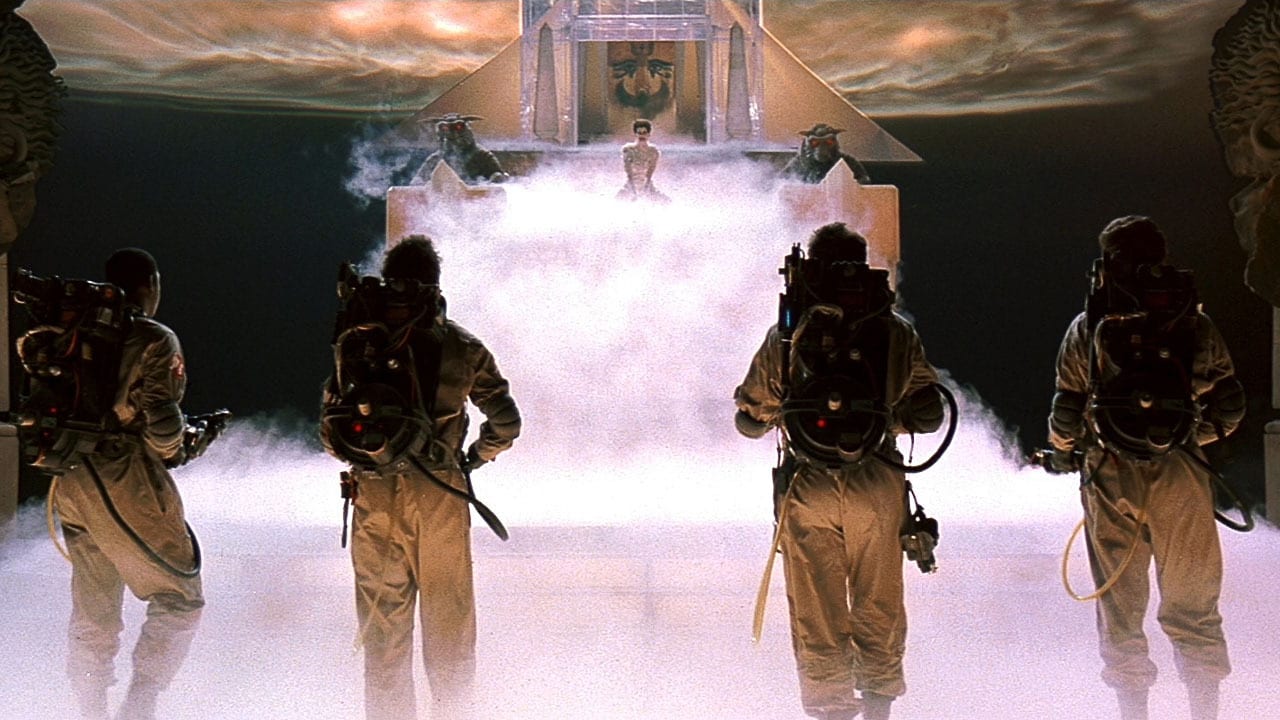

Of course, Ghostbusters is not just a comedy; that was my theory all the way up at the beginning. And part of what makes it so magically weird is the juxtaposition of this very laconic comic mood piece, loose and unstructured and improvised, with the planning-intensive visual effects that are found throughout the movie. A juxtaposition, not a conflict; for despite the odds, Ghostbusters never feels the strain of trying to bring together two apparently incompatible modes of storytelling. Credit for this must go to director Ivan Reitman, a quintessentially '80s director who always seemed to be a step or two behind such other popcorn-fantasy maestros as Robert Zemeckis, Joe Dante, or Richard Donner. Even in Ghostbusters, he doesn't do anything that I'd be inclined to point towards as particularly inspired, visually: perhaps owing to the complexity of so many of the images, the framing throughout the film is rather perfunctory than visionary, though the great cinematographer László Kovács did what he could to add some texture with lighting, and to keep the dirty tactility of New York more or less intact

Still, a film with as many competing modes as Ghostbusters could have easily fallen apart without a strong guiding hand; and this Reitman provided (as he did not, years later, in the similar Evolution). Even given some visual effects that haven't aged well (the worst of them, I suspect, already looked reedy in 1984), there's a real kick to several of the scenes, which I well recall flipped my shit back when I could still count my age using one digit, and while the horror is definitely of the family-friendly sort, it's horror nonetheless; Kovács's aforementioned lighting and Elmer Bernstein's dissonant score do a lot to make certain of that. And yet, the horror and the comedy merge seemlessly, even within the space of a single scene (in Moranis's performance, they merge into the same moment at times). Ghostbusters is definitely a comedy first, a horror film second, and a science fiction film only in the incidentals; but a successful enough hybrid of those things that it would be wrong to try to limit it generically.

As it works despite throwing together seemingly incompatible genres together; thus does it work despite being a bit of a narrative shambles; despite being visually unremarkable in some ways and plainly incomplete in others. It works almost solely because of attitude and charisma. If it sounds odd to use the word "charisma" in relation to a movie, well... that's the charm of Ghostbusters. It's such a singular beast, all sorts of angles and ideas jutting out of it, held together by its onscreen insouciance. Or to put it another way: when a film is this divinely entertaining, then it works. And few American movies from the 1980s work nearly as well, despite being, according to all good sense, "better".

Reviews in this series

Ghostbusters (I. Reitman, 1984)

Ghostbusters II (I. Reitman, 1989)

Ghostbusters (Feig, 2016)

Ghostbusters: Afterlife (J. Reitman, 2021)

Even for a decade in which the high-concept comedy reached its apex, there's something exceptionally high-concept about Ghostbusters: a horror and science-fiction hybrid whose state-of-the-art visual effects were so damn state-of-the art that the film still wasn't quite finished when it premiered in June, 1984, and yet at heart it's just a buddy comedy, just a tale of the geek and the wiseacre like a number of significantly less costly films from the same period.

Of course, given that we hardly recall most of those other movies even with the haze of nostalgia, while Ghostbusters remains as iconic a pop culture touchstone as any other movie from that decade (I can wax all the rhapsodic I want to over The Princess Bride, for example, but must always finally acknowledge that nobody - or only a teeny number of people - would be breathlessly excited for a first-person Princess Bride video game in this day and age), I don't mean to suggest that its big-budget somehow makes it a shallower thing: the very reason for its longevity has everything to do with its "bigness", its costly high-concept ambition which lends the film a kind of grandeur and impressiveness that sets off its resolutely intimate, human-sized comedy and makes it seem all the funnier for the contrast (a similar dynamic drives Men in Black, which has long struck me as the last of the great '80s action-comedies, stranded out in the back half of the 1990s).

For, taken strictly as a comedy and nothing else, Ghostbusters has a very definite loose and ultra-casual feel to it, born of the low-key genial good humor typical of writers Dan Aykroyd and Harold Ramis in those days, and carried further still by a clutch of lead performances that seem to have the shrugged-off sense of improvisation (the top-billed star, a certain Bill Murray, may indeed have improvised a great deal of his work, although how much varies depending on the source you follow). It's not hard to see the creators' background in projects like The Blues Brothers and Caddyshack shining through: movies that are very much in a chilled-out, "we're all just hanging around, being goofy" sort of mood.

Indeed, so casual and cool is the movie, it's altogether shaggy- but just in case, I should quickly outline the plot, I suppose. Three parapsychology professors in New York, Drs. Peter Venkman (Murray), Ray Stantz (Aykroyd) and Egon Spengler (Ramis), are given the boot when their school determines that they're layabouts spending too much money on go-nowhere research. And we have every reason to side with the school, given that the first we see of these gentlemen is Venkman rigging an ESP test to favor a pretty girl that he'd self-evidently like to screw. Deprived of income and a place to conduct Stantz and Spengler's experiments on ghostly phenomenon, the trio manage to set themselves up as New York's only paranormal exterminators, and in just a little while they've proven themselves both as scientists and as public servants. Just in time, too, for the recent uptick in ghost activity in the city is tied to a forgotten Sumerian god called "Gozer" - and whatever Gozer is, it has a particular interest in Dana Barrett (Sigourney Weaver), a musician whom Venkman has been courting, mostly without success.

Now then, that shagginess: the plot of the film is the investigation into stopping Gozer's return, and the movie is well aware of it. But everything that gets us to that point is slapped together; frankly, Ghostbusters has a broken first act, in which we are introduced to our three characters and their paranormal interests, shown the creation of their science and their company, introduced to their snippy receptionist, Janine Melnitz (Annie Potts, a dismally under-used actress whom I have loved since before I can remember - any other fans of the long-extinct sitcom Love & War out there?), and their new recruit, Winston Zeddmore (Ernie Hudson), and given quite a few scoops of foreshadowing, and all of it done so lazily that it would get a failing grade in any screenwriting class in the world. A great deal of information is simply posited, and we damn well better be okay with it; details are thrown out that seem to tie back in to nothing at all (one example from a sea of them: with the money gained from a third mortgage on a single-family home, the boys are able to finance what must be hundreds of thousands of dollars of equipment); arguably the most interesting part of the whole narrative, the ghostbusters' rise from crackpots to national celebrities, is covered in a montage set to Ray Parker's inescapable "Ghostbusters" theme song.

This is not one of those insights that grabbed me as I discovered a beloved slice of childhood to be a shell of what I remembered. Unlike a lot of films that I wore out on VHS, I've seen Ghostbusters frequently - prior to re-watching it for this review, it couldn't have been even two years since I saw it last. And here's the important thing: prior to re-watching it for review, I had never thought about the first act as being dysfunctional in any way. And that's why I have chosen to call it "shaggy": it's unkempt and messy and doesn't really work, except it really works. Which brings us back to the loosey-goosey casualness, and the irremovable anchor brought to the film by the Murray-Aykroyd-Ramis triumvirate.

(Incidentally, I feel terrible for Hudson: it must be thankless than playing the fourth man in a three-man show, though it wasn't always meant to be. In the early stages, his role was intended to be longer, a vehicle for Eddie Murphy, who turned it down in favor of Beverly Hills Cop. A good thing, too: the slacker-ish, buddy-movie vibe would have been seriously damaged by a more prominent role for Zeddmore, especially one with Murphy's generally more manic persona. And the jockeying for prominence between him and Murray would have been intolerable, although it's equally likely that another actor would have been cast as Venkman in this scenario).

Whether by design, accident, or after-the-fact stroke of genius in the editing room, Ghostbusters is Bill Murray's movie. Without Aykroyd and Ramis to bounce his sardonic delivery off of, it's true that there'd be nothing for him to do; but without his performance, in which he forever crystallised his persona as a sarcastic & weary, but oddly likable smart-ass, the simultaneously breezy and snotty mood of the movie simply would not exist. It's hard to believe until you start looking for it, how much of Ghostbusters consists of nothing but Murray's reactions to things: to Ramis's deadpan technobabble, to William Atherton's prissy EPA inspector, to Weaver's prickly charm (incidentally, with the intensely wonderful chemistry between Murray and Weaver on display here, I consider it nothing shy of a crime that they never made a movie together outside of this franchise). Not to diminish the other actors' contributions: Aykroyd in particular has some entirely marvelous lines and moments, and Rick Moranis's smallish role as the twerpy accountant Louis Tully is a tiny comic gem, albeit one that largely exists in some totally different movie. I just feel, steadfastly, that it is Murray who sets the comic tone, and the other performers simply follow in his wake.

Of course, Ghostbusters is not just a comedy; that was my theory all the way up at the beginning. And part of what makes it so magically weird is the juxtaposition of this very laconic comic mood piece, loose and unstructured and improvised, with the planning-intensive visual effects that are found throughout the movie. A juxtaposition, not a conflict; for despite the odds, Ghostbusters never feels the strain of trying to bring together two apparently incompatible modes of storytelling. Credit for this must go to director Ivan Reitman, a quintessentially '80s director who always seemed to be a step or two behind such other popcorn-fantasy maestros as Robert Zemeckis, Joe Dante, or Richard Donner. Even in Ghostbusters, he doesn't do anything that I'd be inclined to point towards as particularly inspired, visually: perhaps owing to the complexity of so many of the images, the framing throughout the film is rather perfunctory than visionary, though the great cinematographer László Kovács did what he could to add some texture with lighting, and to keep the dirty tactility of New York more or less intact

Still, a film with as many competing modes as Ghostbusters could have easily fallen apart without a strong guiding hand; and this Reitman provided (as he did not, years later, in the similar Evolution). Even given some visual effects that haven't aged well (the worst of them, I suspect, already looked reedy in 1984), there's a real kick to several of the scenes, which I well recall flipped my shit back when I could still count my age using one digit, and while the horror is definitely of the family-friendly sort, it's horror nonetheless; Kovács's aforementioned lighting and Elmer Bernstein's dissonant score do a lot to make certain of that. And yet, the horror and the comedy merge seemlessly, even within the space of a single scene (in Moranis's performance, they merge into the same moment at times). Ghostbusters is definitely a comedy first, a horror film second, and a science fiction film only in the incidentals; but a successful enough hybrid of those things that it would be wrong to try to limit it generically.

As it works despite throwing together seemingly incompatible genres together; thus does it work despite being a bit of a narrative shambles; despite being visually unremarkable in some ways and plainly incomplete in others. It works almost solely because of attitude and charisma. If it sounds odd to use the word "charisma" in relation to a movie, well... that's the charm of Ghostbusters. It's such a singular beast, all sorts of angles and ideas jutting out of it, held together by its onscreen insouciance. Or to put it another way: when a film is this divinely entertaining, then it works. And few American movies from the 1980s work nearly as well, despite being, according to all good sense, "better".

Reviews in this series

Ghostbusters (I. Reitman, 1984)

Ghostbusters II (I. Reitman, 1989)

Ghostbusters (Feig, 2016)

Ghostbusters: Afterlife (J. Reitman, 2021)