Savage animals

A previous version of this review appeared at the Film Experience.

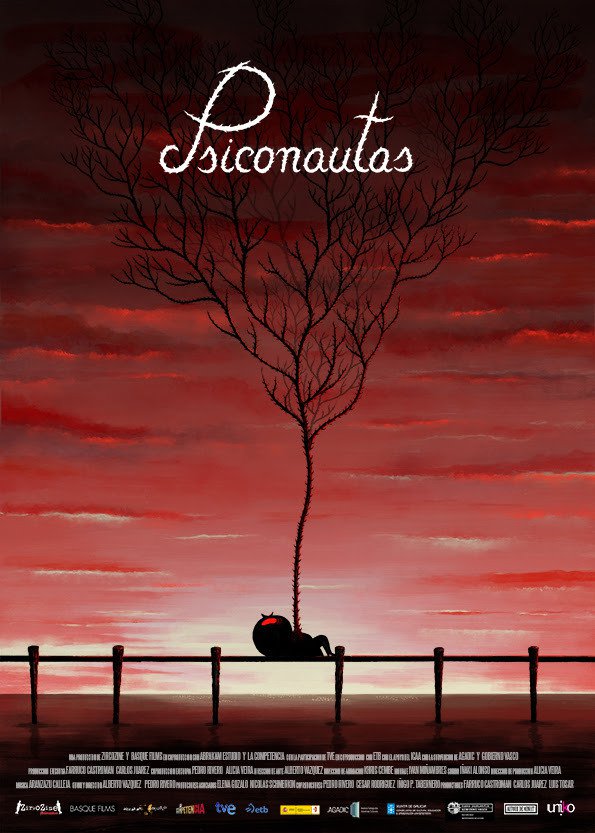

In 2011, Alberto Vázquez and Pedro Rivero co-directed a very dark-hearted short film called Birdboy, based on Vázquez's comic Psiconautas. It left only a bit of an impression on me at the time, but over the years has clung voraciously to the lower tiers of my consciousness as one of the more distinctive animated shorts of the 2010s. And so I was more than a little curious to hear that the directors had a feature-length... sequel? Expansion? Spin-off? Anyway, in 2015, they released Birdboy: The Forgotten Children, a film that has Birdboy sitting down there in its backstory, though I'm not sure that one needs to have seen the original to make any sense of the new film. On the other hand it's short, it's free online, and it arguably has the more aggressively unusual aesthetic, so there's no reason not to check it out.

Like the short before it, The Forgotten Children gets most of its mileage from a very simple, very straightforward contrast: this is a film about cute, silly talking animals warped into a portrait of the world as bleak, hopeless hell. It's psychological horror, as much as it belongs to any particular genre, but that's not really enough to communicate the sheer, visceral nastiness of this film. It's a drawn-out, upsetting 76 minute visit to a dead world, putrescent and cruel, with the survivors still tottering around on the corpse. And they are the cute little fuzzy things of any random children's cartoon. It's designed to work on you by perverting one of the most blithely innocent visual styles imaginable (the characters are drawn as smooth, round shapes in blanket-soft pastel colors) in both the nihilistic content of the story and the grotesque content of the images. You just haven't seen ironic counterpoint until you watch the silhouettes of cartoon animals stripped to the bone in a nuclear blast, something that has come and gone before the film's five-minute mark.

There's no real story to speak of, through there are several intersecting scenarios that all take place on a post-apocalyptic island that still appears to think that civilization is going on. The primary one of these follows a trio of adolescent animals, cute as plush toys, as they navigate the ruins of their world and the brutality that has taken hold as the only real form of interpersonal interaction. Dinki (Andrea Alzuri) is a white mouse, chafing under the repressive religiosity of her stepfather and mother; Sandra (Eba Ojanguren) is a blue rabbit experiencing violent auditory hallucinations, which manifest as little pitch black rabbits with piercing red eyes crawling atop her head; Little Fox (Josu Cubero) is a sensitive, fragile soul, who wanders through the movie with those two as his best friends, looking like everything he sees is going to make him burst into tears. Dinki was once in love with Birdboy, a hollow-eyed skeletal figure in a funereal suit, who nervously skitters around the woods, and she still helps him by hiding small caches of pills - what they're for isn't clear, but they're probably related to whatever sickness has him coughing up blood. Birdboy spends his days evading the cops, who suspect him of dealing drugs to schoolchildren, while he uses heroin to keep at bay his nightmare visions of crow-like demons ripping his organs out. He gets his supply from Zacarías (Jon Goiri), a pig fisherman with his own personal anguish, as he tends to his obsese, addict mother.

That gives us, I think, a fairly decent sense of how this world is put together, with several colorful characters, drawn in playful details, all being crushed down in a universe that knows only suffering. It's a movie that posits talking alarm clocks that have been programmed with the capacity to feel terror and pain, and inflatable pool toys for whom the prospect of being deflated is a matter of existential panic. Fun stuff all of it, drenched in an aesthetic of pure raw dread: there are nightmare visions in this film that use the mutability of animated bodies and the inconsistency of animated space to depict some legitimately terrifying moments of unearthly violence. The depiction of drug hallucinations, in particular, as slithering black objects - a giant spider, the raving things that Birdboy sees whenever he tries to recall his life before the fall - is acutely distressing, an intrusion of cosmic darkness into a film that already places its sweet characters with their expressive line-drawing faces into a hellworld of broken shapes and toxic colors. This is as visceral a horror film as I have seen in the 2010s, and it speaks to the unique power of animation to get at that effect: a world that can be depicted with the simple primacy and instability of a cartoon landscape is one where horror can erupt without warning at any place.

If that sounds just too damn dark for its own good, well, that's because it is. The Forgotten Children walloped me, and I do like a good walloping; but it's so very good at doing this that I felt like I'd been rescued from drowning when it was over. 76 minutes is not a long time; I am, however, enormously grateful that it wasn't longer. This is a deeply uncomfortable film to watch, partially from its content, more from the way that content feels so keenly like a violation of the contract between content and form. The simple line drawings and pleasant colors butt up against the violence, the terror, and the decayed world being depicted in a most anxiety-forming way. It's like a middle-school notebook filled with the ravings of a millenarian street preacher; an apparent children's film, with the soul of a Scandinavian art film. There's real power here; I won't pretend that I always liked how the film made me feel, but the intensity of that feeling is remarkable, a firm rebuke to the idea that animated films should be comforting or domesticated in some way. Your mileage will undoubtedly vary as to whether this is to be sought out or not, but it hits hard and it doesn't let up, and its considerably empathetic depiction of pain makes for an unexpectedly humane film, regardless if the humans are four-foot-tall talking mice.

In 2011, Alberto Vázquez and Pedro Rivero co-directed a very dark-hearted short film called Birdboy, based on Vázquez's comic Psiconautas. It left only a bit of an impression on me at the time, but over the years has clung voraciously to the lower tiers of my consciousness as one of the more distinctive animated shorts of the 2010s. And so I was more than a little curious to hear that the directors had a feature-length... sequel? Expansion? Spin-off? Anyway, in 2015, they released Birdboy: The Forgotten Children, a film that has Birdboy sitting down there in its backstory, though I'm not sure that one needs to have seen the original to make any sense of the new film. On the other hand it's short, it's free online, and it arguably has the more aggressively unusual aesthetic, so there's no reason not to check it out.

Like the short before it, The Forgotten Children gets most of its mileage from a very simple, very straightforward contrast: this is a film about cute, silly talking animals warped into a portrait of the world as bleak, hopeless hell. It's psychological horror, as much as it belongs to any particular genre, but that's not really enough to communicate the sheer, visceral nastiness of this film. It's a drawn-out, upsetting 76 minute visit to a dead world, putrescent and cruel, with the survivors still tottering around on the corpse. And they are the cute little fuzzy things of any random children's cartoon. It's designed to work on you by perverting one of the most blithely innocent visual styles imaginable (the characters are drawn as smooth, round shapes in blanket-soft pastel colors) in both the nihilistic content of the story and the grotesque content of the images. You just haven't seen ironic counterpoint until you watch the silhouettes of cartoon animals stripped to the bone in a nuclear blast, something that has come and gone before the film's five-minute mark.

There's no real story to speak of, through there are several intersecting scenarios that all take place on a post-apocalyptic island that still appears to think that civilization is going on. The primary one of these follows a trio of adolescent animals, cute as plush toys, as they navigate the ruins of their world and the brutality that has taken hold as the only real form of interpersonal interaction. Dinki (Andrea Alzuri) is a white mouse, chafing under the repressive religiosity of her stepfather and mother; Sandra (Eba Ojanguren) is a blue rabbit experiencing violent auditory hallucinations, which manifest as little pitch black rabbits with piercing red eyes crawling atop her head; Little Fox (Josu Cubero) is a sensitive, fragile soul, who wanders through the movie with those two as his best friends, looking like everything he sees is going to make him burst into tears. Dinki was once in love with Birdboy, a hollow-eyed skeletal figure in a funereal suit, who nervously skitters around the woods, and she still helps him by hiding small caches of pills - what they're for isn't clear, but they're probably related to whatever sickness has him coughing up blood. Birdboy spends his days evading the cops, who suspect him of dealing drugs to schoolchildren, while he uses heroin to keep at bay his nightmare visions of crow-like demons ripping his organs out. He gets his supply from Zacarías (Jon Goiri), a pig fisherman with his own personal anguish, as he tends to his obsese, addict mother.

That gives us, I think, a fairly decent sense of how this world is put together, with several colorful characters, drawn in playful details, all being crushed down in a universe that knows only suffering. It's a movie that posits talking alarm clocks that have been programmed with the capacity to feel terror and pain, and inflatable pool toys for whom the prospect of being deflated is a matter of existential panic. Fun stuff all of it, drenched in an aesthetic of pure raw dread: there are nightmare visions in this film that use the mutability of animated bodies and the inconsistency of animated space to depict some legitimately terrifying moments of unearthly violence. The depiction of drug hallucinations, in particular, as slithering black objects - a giant spider, the raving things that Birdboy sees whenever he tries to recall his life before the fall - is acutely distressing, an intrusion of cosmic darkness into a film that already places its sweet characters with their expressive line-drawing faces into a hellworld of broken shapes and toxic colors. This is as visceral a horror film as I have seen in the 2010s, and it speaks to the unique power of animation to get at that effect: a world that can be depicted with the simple primacy and instability of a cartoon landscape is one where horror can erupt without warning at any place.

If that sounds just too damn dark for its own good, well, that's because it is. The Forgotten Children walloped me, and I do like a good walloping; but it's so very good at doing this that I felt like I'd been rescued from drowning when it was over. 76 minutes is not a long time; I am, however, enormously grateful that it wasn't longer. This is a deeply uncomfortable film to watch, partially from its content, more from the way that content feels so keenly like a violation of the contract between content and form. The simple line drawings and pleasant colors butt up against the violence, the terror, and the decayed world being depicted in a most anxiety-forming way. It's like a middle-school notebook filled with the ravings of a millenarian street preacher; an apparent children's film, with the soul of a Scandinavian art film. There's real power here; I won't pretend that I always liked how the film made me feel, but the intensity of that feeling is remarkable, a firm rebuke to the idea that animated films should be comforting or domesticated in some way. Your mileage will undoubtedly vary as to whether this is to be sought out or not, but it hits hard and it doesn't let up, and its considerably empathetic depiction of pain makes for an unexpectedly humane film, regardless if the humans are four-foot-tall talking mice.

Categories: animation, coming-of-age, horror, sassy talking animals, spanish cinema, worthy sequels