Summer of Blood: Don't fuck with the Chuck

I am not speaking for the majority when I suggest that Child's Play 2 is, despite all reason and rationality, a sort of decent horror movie, particularly in the context of being a slasher sequel from 1990. But I will stand firm in this belief.

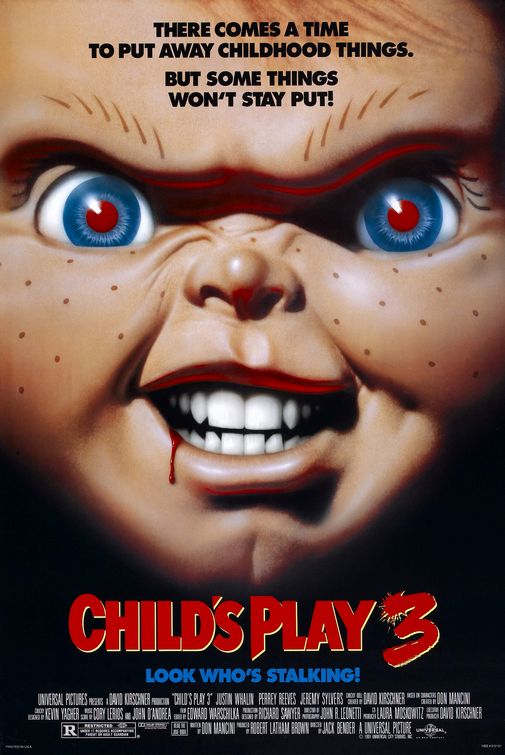

No such bravery on my part in the case of Child's Play 3, a film cranked out less than 11 months after its immediate predecessor, not because the series' writer Don Mancini and producer David Kirschner had thought themselves up some amazing new hook that simply would not wait even one solitary moment, but because Universal - who'd bought the franchise from United Artists after the first Child's Play in 1988 - wanted to keep hammering away at their new brand name before the luster had worn off. Indeed, Child's Play 2 pulled down around $28 million during its release (not a terribly impressive sum in absolute terms, but pretty healthy for an R-rated horror film of that vintage, and highly profitable), though according to Mancini in interviews, the order for a third entry came before the second was even completed. As he continues to tell it, the result was a desperate, flailing attempt to come up with any idea at all despite his being tapped out so soon after the first sequel; he maintains still that Child's Play 3 is the worst of the franchise. History vindicates him in this belief.

Here is what Mancini was able to puke out on the spur of the moment: eight years after the murderous talking doll Chucky (voiced still by the invaluable Brad Dourif) was melted into a pile of nondescript matter on the floor of the Play Pals, Inc. factory, 16-year-old Andy Barclay (Justin Whalin replacing Alex Vincent, for the obvious reasons) has completed his sullen journey through foster homes by winding up in military school. Around the same time, Play Pals manages to rise from bankruptcy, or whatever happened to it, and re-starts the Good Guys doll line (the TV commercial cheerily insists that this is the new "Good Guy doll of the '90s!", which is something nobody would probably say in 1998, when this is theoretically set, though it is true that a toy reboot based on the grounds that it's better to re-hash past successes than create new ones is quintessentially of the '90s. Also, remember how back in the first half of the '90s, people used to chirp "It's the '90s" whenever making note of some overinflated sociological trend, as though that phrase meant fuck all. "It's the '90s". Really, no shit? Well thanks for telling me, because I've been in a motherfucking coma since the George Bush inauguration. Goddamn, I hated the '90s). During the re-opening of the Good Guys production floor, which does not look half so improbably magical as it did in the last film, a crane plucks up Chucky's bleeding remains, and some of the blood dribbles into a vat of plastic. Naturally enough, this means that Chucky's soul ends up in a new Good Guy doll, though it would seem like the sensible thing would be for it to end up in all the new Good Guy dolls, so the film's climax should have borne witness to a veritable army of Chuckies. Good Lord, Mancini, the idea was right there. How could you possibly have missed it?

The re-born Chucky manages to sneak his way into a board meeting to kill Sullivan (Peter Haskell), the wretched CEO of Play Pals, not for any reason that makes specific story sense, but in recognition maybe of the undeniable truth that he ought to have been killed in Child's Play 2. It's only now that we finally meet Andy in military school, and he's having a rough go of it, with the absolutely intolerable shitheel cadet Shelton (Travis Fine) taking great delight in making the new recruit suffer. But it's all good, because Andy just got a package in the mail. A big package. No points for guessing what murderous toy with the soul of a serial killer lurks inside, though I will be happy to hear any theories as to how Chucky managed to post himself with a dead CEO in the background.

While Child's Play and Child's Play 2 both enjoyed what I would consider as a paucity of narrative content relative to their running time, Child's Play 3 goes all the way to the other end: in its 90 minutes (the longest in the series to that point), it crams incident after incident, juggling two entirely disparate subplots for quite a while - Andy problems in school with Shelton and the pretty De Silva (Perrey Reeves) on the one hand, Chucky's attempts to drop his soul into the youngest cadet of them all, little Ronald Tyler (Jeremy Sylvers), on the other; though Andy is aware of Chucky's presence throughout and the two subplots are never entirely disconnected - and once again recreating the rare feat that seems to be a Child's Play specialty: it buzzes by like it's on fire, feeling not remotely as long as it actually is, and though that's a blessing for Child's Play 3 is a terrible movie, and 90 long minutes of it would suck, I would not lightly pass over the fact that these are, at their worst, still rather sprightly movies, and that assuredly is not true of all horror franchises - Witchcraft III also came out in 1991, as we must never forget.* Child's Play 3 might suck - nay, it does suck - and its whole-hearted sucking might be a side-effect of its remarkable lack of imagination as part of the big huge redundant world of 1990s slashers, but by God, it's not boring. That's what having a wisecracking doll for your psychopath will do for you.

Still and all, it is unquestionably the case that Mancini and director Jack Bender are afflicted with a bad case of not giving a damn. For Mancini, these just means a whole lot of undernourished characters and sequences that seem plucked out of absolutely nowhere at all - never more obvious than the odd placement of a carnival of some kind just down the hill from the school, all the better to stage the climactic face-off inside a haunted house ride that combines the mechanics of a dark ride and a roller coaster in a manner that makes absolutely no damn sense, at least to me. The war games sequence, in which Chucky replaces all the paintballs of one side with live rounds (did you know that paint guns and military rifles use the same exact size of ammunition? Don Mancini does!), and in which only one person ends up being shot, is another scene that smacks of creative floundering. "I got it, Chucky in a war zone! That makes perfect sense for a two-foot doll with the soul of a murderer!"

One of the worst elements of Mancini's script, however, is one of the most explicable: Tyler, wildly out of place around so many teenagers, plugged in solely because tiny little Chucky is only good at menacing children (though he only kills adults, so that logic doesn't hold even within the movie itself), and so a child must be around, logic be damned; not only is Tyler a barbarically functional character, he does not for a second convince us that he is a real boy and not a screenwriter's version of same.

As for Bender, a television director who as only occasionally dabbled in features, his aesthetic is one that underscores in every way possible the cheapness and tackiness of the film's sets: he even manages to make the real-life Kemper Military School of Boonville, Missouri look like a set. Everything is just a little overlit and a little too close and the actors all seem a little too broad. The whole effect is honestly very typical of a cheap '90s horror movie, but just because something is typical, does not mean it is not aggravating. The very opposite, in fact.

And thus it came to be that a series that was, in general, decent enough, took a sharp plunge into crapitude, like a hundred cash-in horror pictures before and a hundred after. Both Child's Play and Child's Play 2 ultimately came from an honest place; though neither of them are terrifically scary or anything else, at least they have novelty, creativity, and a point of view. Child's Play 3 is strictly going through the motions, colliding chunks of scenario into each other without giving a damn whether the resultant explosion means anything or makes any sense.

It is, in short, a complete and utterly reprehensible exercise in cashing in on the brand name. And in this, at least, we can understand Universal's position: for horror films were and are a great way to make a lot of money from almost not investment; and they were and are such a brand loyalty-driven thing; and after the collapse of the slasher genre in the late '80s, Child's Play was really the only horror franchise that had anything resembling freshness to it. Though not fresh enough, it would seem: Child's Play 3 made less than half of the money of its two predecessors, and left the series on ice for quite a long time, squandering whatever good will it had rustled up before then. Even in as blighted a time as the first half of the 1990s, horror fans could afford to be a little picky.

Body Count: 7, which slightly improves upon its immediate predecessor, but not in the same manner of rank desperation way evinced by the rest of the movie. A kind of integrity, I guess.

Reviews in this series

Child's Play (Holland, 1988)

Child's Play 2 (Lafia, 1990)

Child's Play 3 (Bender, 1991)

Bride of Chucky (Yu, 1998)

Seed of Chucky (Mancini, 2004)

Curse of Chucky (Mancini, 2013)

Cult of Chucky (Mancini, 2017)

*Moreover, it also followed a 1988 original and a 1990 Part 2, which makes it all even creepier.

No such bravery on my part in the case of Child's Play 3, a film cranked out less than 11 months after its immediate predecessor, not because the series' writer Don Mancini and producer David Kirschner had thought themselves up some amazing new hook that simply would not wait even one solitary moment, but because Universal - who'd bought the franchise from United Artists after the first Child's Play in 1988 - wanted to keep hammering away at their new brand name before the luster had worn off. Indeed, Child's Play 2 pulled down around $28 million during its release (not a terribly impressive sum in absolute terms, but pretty healthy for an R-rated horror film of that vintage, and highly profitable), though according to Mancini in interviews, the order for a third entry came before the second was even completed. As he continues to tell it, the result was a desperate, flailing attempt to come up with any idea at all despite his being tapped out so soon after the first sequel; he maintains still that Child's Play 3 is the worst of the franchise. History vindicates him in this belief.

Here is what Mancini was able to puke out on the spur of the moment: eight years after the murderous talking doll Chucky (voiced still by the invaluable Brad Dourif) was melted into a pile of nondescript matter on the floor of the Play Pals, Inc. factory, 16-year-old Andy Barclay (Justin Whalin replacing Alex Vincent, for the obvious reasons) has completed his sullen journey through foster homes by winding up in military school. Around the same time, Play Pals manages to rise from bankruptcy, or whatever happened to it, and re-starts the Good Guys doll line (the TV commercial cheerily insists that this is the new "Good Guy doll of the '90s!", which is something nobody would probably say in 1998, when this is theoretically set, though it is true that a toy reboot based on the grounds that it's better to re-hash past successes than create new ones is quintessentially of the '90s. Also, remember how back in the first half of the '90s, people used to chirp "It's the '90s" whenever making note of some overinflated sociological trend, as though that phrase meant fuck all. "It's the '90s". Really, no shit? Well thanks for telling me, because I've been in a motherfucking coma since the George Bush inauguration. Goddamn, I hated the '90s). During the re-opening of the Good Guys production floor, which does not look half so improbably magical as it did in the last film, a crane plucks up Chucky's bleeding remains, and some of the blood dribbles into a vat of plastic. Naturally enough, this means that Chucky's soul ends up in a new Good Guy doll, though it would seem like the sensible thing would be for it to end up in all the new Good Guy dolls, so the film's climax should have borne witness to a veritable army of Chuckies. Good Lord, Mancini, the idea was right there. How could you possibly have missed it?

The re-born Chucky manages to sneak his way into a board meeting to kill Sullivan (Peter Haskell), the wretched CEO of Play Pals, not for any reason that makes specific story sense, but in recognition maybe of the undeniable truth that he ought to have been killed in Child's Play 2. It's only now that we finally meet Andy in military school, and he's having a rough go of it, with the absolutely intolerable shitheel cadet Shelton (Travis Fine) taking great delight in making the new recruit suffer. But it's all good, because Andy just got a package in the mail. A big package. No points for guessing what murderous toy with the soul of a serial killer lurks inside, though I will be happy to hear any theories as to how Chucky managed to post himself with a dead CEO in the background.

While Child's Play and Child's Play 2 both enjoyed what I would consider as a paucity of narrative content relative to their running time, Child's Play 3 goes all the way to the other end: in its 90 minutes (the longest in the series to that point), it crams incident after incident, juggling two entirely disparate subplots for quite a while - Andy problems in school with Shelton and the pretty De Silva (Perrey Reeves) on the one hand, Chucky's attempts to drop his soul into the youngest cadet of them all, little Ronald Tyler (Jeremy Sylvers), on the other; though Andy is aware of Chucky's presence throughout and the two subplots are never entirely disconnected - and once again recreating the rare feat that seems to be a Child's Play specialty: it buzzes by like it's on fire, feeling not remotely as long as it actually is, and though that's a blessing for Child's Play 3 is a terrible movie, and 90 long minutes of it would suck, I would not lightly pass over the fact that these are, at their worst, still rather sprightly movies, and that assuredly is not true of all horror franchises - Witchcraft III also came out in 1991, as we must never forget.* Child's Play 3 might suck - nay, it does suck - and its whole-hearted sucking might be a side-effect of its remarkable lack of imagination as part of the big huge redundant world of 1990s slashers, but by God, it's not boring. That's what having a wisecracking doll for your psychopath will do for you.

Still and all, it is unquestionably the case that Mancini and director Jack Bender are afflicted with a bad case of not giving a damn. For Mancini, these just means a whole lot of undernourished characters and sequences that seem plucked out of absolutely nowhere at all - never more obvious than the odd placement of a carnival of some kind just down the hill from the school, all the better to stage the climactic face-off inside a haunted house ride that combines the mechanics of a dark ride and a roller coaster in a manner that makes absolutely no damn sense, at least to me. The war games sequence, in which Chucky replaces all the paintballs of one side with live rounds (did you know that paint guns and military rifles use the same exact size of ammunition? Don Mancini does!), and in which only one person ends up being shot, is another scene that smacks of creative floundering. "I got it, Chucky in a war zone! That makes perfect sense for a two-foot doll with the soul of a murderer!"

One of the worst elements of Mancini's script, however, is one of the most explicable: Tyler, wildly out of place around so many teenagers, plugged in solely because tiny little Chucky is only good at menacing children (though he only kills adults, so that logic doesn't hold even within the movie itself), and so a child must be around, logic be damned; not only is Tyler a barbarically functional character, he does not for a second convince us that he is a real boy and not a screenwriter's version of same.

As for Bender, a television director who as only occasionally dabbled in features, his aesthetic is one that underscores in every way possible the cheapness and tackiness of the film's sets: he even manages to make the real-life Kemper Military School of Boonville, Missouri look like a set. Everything is just a little overlit and a little too close and the actors all seem a little too broad. The whole effect is honestly very typical of a cheap '90s horror movie, but just because something is typical, does not mean it is not aggravating. The very opposite, in fact.

And thus it came to be that a series that was, in general, decent enough, took a sharp plunge into crapitude, like a hundred cash-in horror pictures before and a hundred after. Both Child's Play and Child's Play 2 ultimately came from an honest place; though neither of them are terrifically scary or anything else, at least they have novelty, creativity, and a point of view. Child's Play 3 is strictly going through the motions, colliding chunks of scenario into each other without giving a damn whether the resultant explosion means anything or makes any sense.

It is, in short, a complete and utterly reprehensible exercise in cashing in on the brand name. And in this, at least, we can understand Universal's position: for horror films were and are a great way to make a lot of money from almost not investment; and they were and are such a brand loyalty-driven thing; and after the collapse of the slasher genre in the late '80s, Child's Play was really the only horror franchise that had anything resembling freshness to it. Though not fresh enough, it would seem: Child's Play 3 made less than half of the money of its two predecessors, and left the series on ice for quite a long time, squandering whatever good will it had rustled up before then. Even in as blighted a time as the first half of the 1990s, horror fans could afford to be a little picky.

Body Count: 7, which slightly improves upon its immediate predecessor, but not in the same manner of rank desperation way evinced by the rest of the movie. A kind of integrity, I guess.

Reviews in this series

Child's Play (Holland, 1988)

Child's Play 2 (Lafia, 1990)

Child's Play 3 (Bender, 1991)

Bride of Chucky (Yu, 1998)

Seed of Chucky (Mancini, 2004)

Curse of Chucky (Mancini, 2013)

Cult of Chucky (Mancini, 2017)

*Moreover, it also followed a 1988 original and a 1990 Part 2, which makes it all even creepier.

Categories: horror, needless sequels, slashers, summer of blood, violence and gore