The kind of a girl that makes the news of the world

Errol Morris made his name as a documentarian on a run of captivating films about remarkably weird human beings: Gates of Heaven, Vernon, Florida, and the like. But after the success of his mesmerising television series First Person in the early years of the '00s, he did as so many liberal filmmakers did in the dark days of the George W. Bush presidency, and made political films. The first of these, The Fog of War, is pretty much a good thing; the second, Standard Operating Procedure is pretty much obvious and superficial, the one and only non-fiction Morris film that I for one have essentially no use for whatsoever. But what the hell, it was 2008. That's the kind of thing that happened back then.

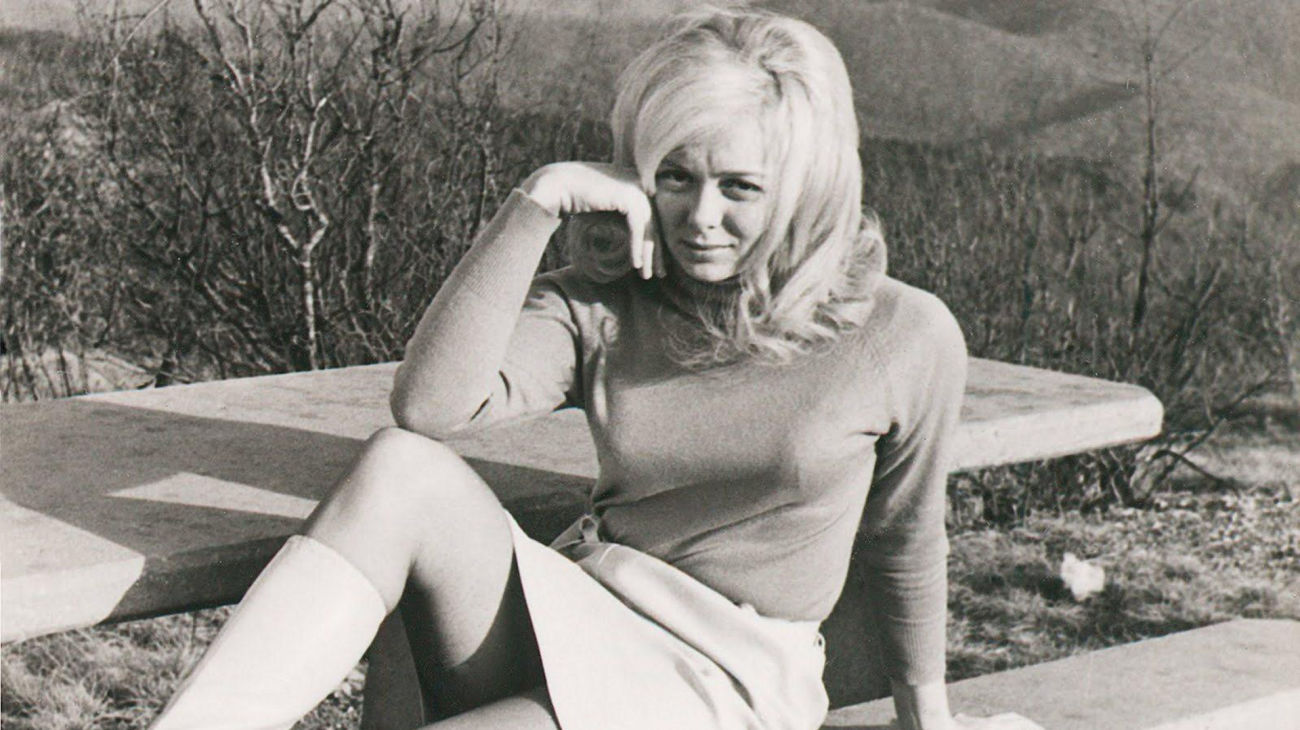

Still and all, it's extremely gratifying to find Morris back in his customary form with Tabloid, a movie whose title and milieu might make it seem like the director has fallen into a huge pot of luck, what with his movie making its limited release crawl through the U.S. right on the eve of Rupert Murdoch's fall from grace in Great Britain; but the reality of Tabloid is blessedly far removed from topicality or sociological import. We're back squarely and delightfully in character study land, with Morris training his famed Interrotron (a camera that lets him look directly into his subjects' eyes, while it looks like they're staring into the camera) on the story of Joyce Bernann McKinney, a North Carolina girl who was once Miss Wyoming and in 1977 and 1978 was at the center of a remarkable story of abduction, rape, and Mormonism spanning two continents.

The short version of the facts that everybody agrees on: McKinney fell passionately in love with a man a few years her junior, Kirk Anderson, a newly-minted Mormon Elder. When he was sent on his mission trip to England, McKinney was certain that the the Church had shipped him off to "save" him from their love, and accompanied by her friend, the late Keith May, a gym-rat bodyguard and recreational pilot Jackson Shaw, she jetted across the Atlantic to find him. After she made contact, the Mormons he was journeying with lost track of him, and from here on out, "facts" stop being something you can count on very much. According to McKinney, Anderson came with her willingly, and for a few days they enjoyed an especially beautiful kind of perfect love, until his religious leaders took him back and brainwashed him. According to Anderson's later account, he was kidnapped at gunpoint and raped. And this is not, incidentally, where the story begins to get really interesting, because as the British population grew captivated by the story, an honest-to-God yellow journalism war broke out between the Daily Express (which defended McKinney to the point that it depicted her on its cover as a literal nun) and the Daily Mirror (which scrounged up evidence of her secret life as a prostitute* in the States), and McKinney and May's subsequently fled from Britain. And what happened years later, to bring McKinney back to the public eye, is so god-damned weird that I do not want to spoil the surprise even a little bit.

The Morris who made The Thin Blue Line would be interested in finding out what the truth is beneath all this mess; the Morris who made The Fog of War would at least want to make us think about the inconsistency and unreliability of the individual's perspective. The Morris behind Tabloid, however, has much less sophisticated concerns: his film is often little more than staring with goggle-eyed amazement at the freak show in front of him; the film's title doesn't end up speaking to its intellectual concerns ("Tabloids are symptomatic of humanity's worst kind of prurient interests, and they are more concerned with spectacle than truth"), but to its tone and content ("Oh my God, what the holy hell is going on? This is so fucked up!"). I don't suspect that this is what he set out to do; I think it happened when he got to interview Joyce McKinney, an incredibly charismatic and happy woman who gleefully runs back and forth through her thoughts as they arrive in mostly chronological order, who laughs at her own jokes, who possesses a sense of storybook romance that would make a Disney princess look like a jaded hooker in comparison. That McKinney's version of events is frankly incoherent, nobody could doubt; but the conviction with which she believes it (and unless she is cunning to a degree that nothing else in the film suggests is even remotely possible, she clearly believes in the absolute virgin purity of every word that escapes her lips) is entrancing. I had expected, knowing that McKinney has since sued Morris over her depiction in the film (basically, her argument seems to be "how dare you use a contextual framework for my words, rather than simply releasing the raw interview footage to theaters"), that it would all be exploitative, but McKinney inoculates herself from exploitation by existing in a reality almost cotangent with ours, in which since absolutely nothing untoward happened, there is no shame or infamy in the story.

On the other hand, there may not be a better word than "exploitation" to describe what Tabloid is, given its rather free admission that what makes all this fascinating is how endlessly perverse it all is. The witnesses called in to give their version of events include Shaw and two journalists from opposite sides of the war who both had a good deal of skin in the game, (May is dead; Anderson refused to be interviewed, and in the process made the film better; it couldn't turn into a simple "he said she said" game). Peter Tory of the Express and Kent Gavin of the Mirror; each of them would make a good subject in their own right, as people tend to be when Morris turns his camera on just about anybody (Tory's fascination with bondage and Gavin's gleeful reminiscences about his incredibly sordid detective work prove, if nothing else, that McKinney isn't the only one with a certain perverse air; Shaw's fixation on how much he wanted to have sex with her in 1977 mostly just comes across as sad), but here they only serve to add an anchor based in something resembling the real world to keep McKinney's stories from floating right into outer space.

Morris changes up his style a little bit, relying on pointedly snarky pop culture ephemera (old sitcoms, a ghastly-looking Mormon propaganda cartoon) carved into the surface of the film using a smaller, grainier frame, to suggest in a somewhat halting way how life and media have caved into one another; it's honestly a bit more smug than revelatory, as is his mercilessly ironic use of onscreen text to emphasise certain words in the interviews, though I certainly appreciate that he's willing to play the material as the idiotic comedy it all was in life (all respect to the presumptive rape victim Anderson, but I think the likeliest version of events is the one forwarded by Troy Williams, gay ex-Mormon activist: a shy, flabby Mormon kid had sex, and liked it, and felt really incredibly terrible about liking it, and guilt did the rest) without resorting to making fun of anybody, although the line between making fun of McKinney and simply watching her speak about all the fascinating things on her mind is a narrow one.

I wonder, is that maybe the film's deeper point? McKinney, after all, doesn't see herself as an insane person; she views her loopy romanticism about men, about life, about dogs (but I said I wasn't going to spoil the end!) as perfectly reasonable, just like most of us assume that everything we think or do is at least reasonable, if not normative. Tabloid, perhaps, is the snotty mirror on all of us: push anybody's reasonable beliefs far enough, and they'll look like a ridiculous clown. And at the same time, even the most unreasonable things can be compelling and fascinating when they're told with passion and conviction. The film around McKinney isn't quite sure of what it's about, at times - it's probably the "worst", or at least most aimless, of Morris's films outside of the arid Standard Operating Procedure - but McKinney herself is the sort of arresting figure that you don't shake easily; and though she is a real-life woman, she's also one of the best movie characters of 2011.

Still and all, it's extremely gratifying to find Morris back in his customary form with Tabloid, a movie whose title and milieu might make it seem like the director has fallen into a huge pot of luck, what with his movie making its limited release crawl through the U.S. right on the eve of Rupert Murdoch's fall from grace in Great Britain; but the reality of Tabloid is blessedly far removed from topicality or sociological import. We're back squarely and delightfully in character study land, with Morris training his famed Interrotron (a camera that lets him look directly into his subjects' eyes, while it looks like they're staring into the camera) on the story of Joyce Bernann McKinney, a North Carolina girl who was once Miss Wyoming and in 1977 and 1978 was at the center of a remarkable story of abduction, rape, and Mormonism spanning two continents.

The short version of the facts that everybody agrees on: McKinney fell passionately in love with a man a few years her junior, Kirk Anderson, a newly-minted Mormon Elder. When he was sent on his mission trip to England, McKinney was certain that the the Church had shipped him off to "save" him from their love, and accompanied by her friend, the late Keith May, a gym-rat bodyguard and recreational pilot Jackson Shaw, she jetted across the Atlantic to find him. After she made contact, the Mormons he was journeying with lost track of him, and from here on out, "facts" stop being something you can count on very much. According to McKinney, Anderson came with her willingly, and for a few days they enjoyed an especially beautiful kind of perfect love, until his religious leaders took him back and brainwashed him. According to Anderson's later account, he was kidnapped at gunpoint and raped. And this is not, incidentally, where the story begins to get really interesting, because as the British population grew captivated by the story, an honest-to-God yellow journalism war broke out between the Daily Express (which defended McKinney to the point that it depicted her on its cover as a literal nun) and the Daily Mirror (which scrounged up evidence of her secret life as a prostitute* in the States), and McKinney and May's subsequently fled from Britain. And what happened years later, to bring McKinney back to the public eye, is so god-damned weird that I do not want to spoil the surprise even a little bit.

The Morris who made The Thin Blue Line would be interested in finding out what the truth is beneath all this mess; the Morris who made The Fog of War would at least want to make us think about the inconsistency and unreliability of the individual's perspective. The Morris behind Tabloid, however, has much less sophisticated concerns: his film is often little more than staring with goggle-eyed amazement at the freak show in front of him; the film's title doesn't end up speaking to its intellectual concerns ("Tabloids are symptomatic of humanity's worst kind of prurient interests, and they are more concerned with spectacle than truth"), but to its tone and content ("Oh my God, what the holy hell is going on? This is so fucked up!"). I don't suspect that this is what he set out to do; I think it happened when he got to interview Joyce McKinney, an incredibly charismatic and happy woman who gleefully runs back and forth through her thoughts as they arrive in mostly chronological order, who laughs at her own jokes, who possesses a sense of storybook romance that would make a Disney princess look like a jaded hooker in comparison. That McKinney's version of events is frankly incoherent, nobody could doubt; but the conviction with which she believes it (and unless she is cunning to a degree that nothing else in the film suggests is even remotely possible, she clearly believes in the absolute virgin purity of every word that escapes her lips) is entrancing. I had expected, knowing that McKinney has since sued Morris over her depiction in the film (basically, her argument seems to be "how dare you use a contextual framework for my words, rather than simply releasing the raw interview footage to theaters"), that it would all be exploitative, but McKinney inoculates herself from exploitation by existing in a reality almost cotangent with ours, in which since absolutely nothing untoward happened, there is no shame or infamy in the story.

On the other hand, there may not be a better word than "exploitation" to describe what Tabloid is, given its rather free admission that what makes all this fascinating is how endlessly perverse it all is. The witnesses called in to give their version of events include Shaw and two journalists from opposite sides of the war who both had a good deal of skin in the game, (May is dead; Anderson refused to be interviewed, and in the process made the film better; it couldn't turn into a simple "he said she said" game). Peter Tory of the Express and Kent Gavin of the Mirror; each of them would make a good subject in their own right, as people tend to be when Morris turns his camera on just about anybody (Tory's fascination with bondage and Gavin's gleeful reminiscences about his incredibly sordid detective work prove, if nothing else, that McKinney isn't the only one with a certain perverse air; Shaw's fixation on how much he wanted to have sex with her in 1977 mostly just comes across as sad), but here they only serve to add an anchor based in something resembling the real world to keep McKinney's stories from floating right into outer space.

Morris changes up his style a little bit, relying on pointedly snarky pop culture ephemera (old sitcoms, a ghastly-looking Mormon propaganda cartoon) carved into the surface of the film using a smaller, grainier frame, to suggest in a somewhat halting way how life and media have caved into one another; it's honestly a bit more smug than revelatory, as is his mercilessly ironic use of onscreen text to emphasise certain words in the interviews, though I certainly appreciate that he's willing to play the material as the idiotic comedy it all was in life (all respect to the presumptive rape victim Anderson, but I think the likeliest version of events is the one forwarded by Troy Williams, gay ex-Mormon activist: a shy, flabby Mormon kid had sex, and liked it, and felt really incredibly terrible about liking it, and guilt did the rest) without resorting to making fun of anybody, although the line between making fun of McKinney and simply watching her speak about all the fascinating things on her mind is a narrow one.

I wonder, is that maybe the film's deeper point? McKinney, after all, doesn't see herself as an insane person; she views her loopy romanticism about men, about life, about dogs (but I said I wasn't going to spoil the end!) as perfectly reasonable, just like most of us assume that everything we think or do is at least reasonable, if not normative. Tabloid, perhaps, is the snotty mirror on all of us: push anybody's reasonable beliefs far enough, and they'll look like a ridiculous clown. And at the same time, even the most unreasonable things can be compelling and fascinating when they're told with passion and conviction. The film around McKinney isn't quite sure of what it's about, at times - it's probably the "worst", or at least most aimless, of Morris's films outside of the arid Standard Operating Procedure - but McKinney herself is the sort of arresting figure that you don't shake easily; and though she is a real-life woman, she's also one of the best movie characters of 2011.