Blockbuster History: Men and apes

Every Sunday this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: the prequel/remake/reboot Rise of the Planet of the Apes once again asks the age-old question of what is the line between human and apes, and what does that mean for both species? How are we to live with beings so like ourselves, yet which we insist on perceiving as "dumb animals". Sometimes these questions are addressed in mordant apocalyptic fantasies; sometimes they are addressed in hokey '70s action-comedies.

It's easy to forget, now that he's largely known as the director of middling-to-good Oscarbait, but there was a time when Clint Eastwood was at the very top of Hollywood's A-list - this was when he was still primarily an actor who occasionally dabbled in directing, mind you, and his acting consisted not of the soul-tortured apologias for his wanton, violent excesses that dominated his career from the early '90s until he retired from acting with 2008's Gran Torino; this was still the era of those very same wanton, violent, frequently nasty and misanthropic actioners, and audiences loved them all to bits. It has been said, I do not know on what evidence, that Eastwood was the biggest movie star of the 1970s.

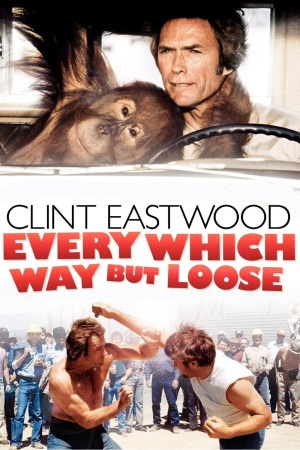

Perhaps already beginning to tire of his Dirty Harry persona, perhaps looking to conquer new horizons, and perhaps just coked out of his mind*, Eastwood took his first major career detour, when he starred in Every Which Way But Loose, a movie written (it is said) for Burt Reynolds, another major star of that time whose career was miles away from Eastwood's. On the one hand: nihilistic cops and cowboys, meting out justice with an icy, even despotic hand. On the other: a grinning, mustached good ol' boy. There is no doubt about the fact that EWWBL feels a hell of a lot more like a Reynolds movie than it feels like anything else in Eastwood's career (except for its own sequel, Any Which Way You Can), what with its aimless, easygoing truck-driving protagonist, its country & Western soundtrack, its slapstick fistfights, it's beer-drinking orangutan.

Yes! A beer-drinking juvenile orangutan named Clyde (the ape actor's name was Manis), and this detail is likely the only reason the film has remained whatsoever current in the popular imagination. "The movie where Clint Eastwood horned in on Burt Reynolds's territory by playing a street-fighting truck driver" would appeal to a much smaller audience of Eastwood completists than would "The movie with Clint Eastwood and an orangutan". I think you don't need to be an Eastwood fan - I think you could out and out hate the man's movies - and still be at least a little bit intrigued by the very perversity of that scenario. And maybe that's the reason for the film's success, or maybe it's testament to just how unthinkably popular Eastwood was in '78 (his kind of box-office popularity literally does not exist in this day and age) that EWWBL ended up as the second-highest-grossing film of the year, behind Superman. For good or ill, we simply do not live in the same kind of world as they did back then.

Clint and an orangutan; that's as good a way to describe the movie as anything, for all the plot it has. In fact, for a solid half-hour - or about a quarter of the total running time - you could be forgiven for doubting that EWWBL had a story at all. It has, instead, scenes in the life of Eastwood's Philo Beddoe, a laid-back sort of man living in Los Angeles, making a living as a bare-knuckle brawler, living with his buddy Orville (Geoffrey Lewis), and Orville's ancient mother, Ma (Ruth Gordon). And Clyde, whom Philo won as part of one fight or another. Philo fights some folks, pisses off a local biker gang, the Black Widows, and falls head over heels for a bar singer, Lynn Halsey-Taylor (Sondra Locke, Eastwood's real-life lover at the time, and his co-star in six separate movies, of which this was the third). It's only when Lynn seemingly evaporates that EWWBL finally decides that watching Philo poking about, being easygoing and laid-back, isn't going to support an entire feature, and so the rudiments, and rudiments only, of a plot begin to kick in. Philo, Clyde and Orville head off to Denver, the only lead they have to Lynn's possible whereabouts, followed by the Black Widows and a pair of pissed-off cops; along the way, Orville falls in love with a girl much younger than he is, the hippie-named Echo (Beverly D'Angelo), though this changes very little other than adding one more voice to the bantering in the truck.

I have now used both "easygoing" and "laid-back" twice apiece, and if I wanted to look any more closely at the film's plot, I'd be obliged to use them over and over again, because EWWBL is almost aggressively modest in its charms and scope. Jokin', fightin', boozin', truckin' - the movie is about simple, working-class things, and it practically forbids you from adding -g to the end of words. It is as conservative - socially and aesthetically - as anything in the famously conservative career of its star. If I were going to be in a judgy mood, I'd call it "redneck", and given the whole Reynold's connection, plus the countrified soundtrack, it's not very daring to wonder if the film might be best fit into the hicksploitation cycle of that decade, disguised only by a flimsy urban setting.

The film is decidedly unsophisticated, not that it's exactly the same thing - it was directed by James Fargo, only lately graduated from the ranks of assistant directors, and a man of profoundly unmemorable visual style - and if there were nothing about it other than the casually dismissive way it treats its women, that would still be enough: Echo is just a flirty sexpot, Ma is just the nutty comic relief who can't drive a car, and Lord, I'd almost rather not think about Lynn, and the heavily sexist way she's disposed of at the end, having outlived her usefulness as a story element. I'd add the film's open mockery of her dreams to make it big as a singer, but then I recall that Eastwood was in love at the time, and perhaps he didn't mean for us to take her wobbly voice as badly as I, at least, did.

All of this - the indifferent direction, the sexism, the blandly reductive "it's fun to watch a guy get in fistfights in lieu of any real narrative" structure (although, that ends up being the film's structure, in an off-kilter way; the climax, and the wrapping-up of Philo's character arc that we didn't even realise existed until that moment, have to do with the big final fight, and not with his chasing Lynn at all) - make certain that EWWBL is not a "good" movie, and the fact that it was greeted with some dismay by the critics of 1978 surprises me not at all. I cannot, however, keep myself from feeling that time has been oddly kind to the movie. As John Huston purred in Chinatown, a slightly older movie that captured the Zeitgeist in a very different way, "Politicians, ugly buildings, and whores all get respectable if they last long enough". And, we might add, bad movies; maybe that's just me. At any rate, compared to a lot of the late-'70s pictures it resembles, EWWBL is just weird enough to work as a fun time capsule in a half-baked sort of way. Maybe it's the spectacle of seeing Eastwood in a mostly straight-up comedy, something as rare now as it was then. Certainly, it's the orangutan; though Clyde ends up being in the movie a lot less than you'd anticipate, given how large he looms in the film's legend (such as it is).

I think it's because he's there in such a matter-of-fact way. A little bit of dialogue to explain things without actually explaining them, and off we go: nobody seems to regard it as noteworthy that Phil travels everywhere with the little hominid, and it takes barely any time at all until Clyde just seems to be another one of the characters, getting in scrapes and getting out of them using his fists and his wit, lucky that all of the antagonists in the movie have the intelligence of damp newsprint. This unresolved strangeness is both part of the movie's magnificently relaxed charm, and something of a challenge to our suspension of disbelief: "Yeah, there's a fucking ape", it seems to say, "and you just have to deal with that. So deal".

The result is that the movie has just enough warp to it that it's interesting in despite of itself, a bizarre missive from another era when beer-drinking orangutans were all in good fun and not kind of off-putting. That's probably not the best reason to watch a movie, and yet it's what kept coming up to me, over and over, as I watched the film: people were absolutely in love with this movie once, and not such a long time ago, and that is amazing to think about. The past is a very weird place, and I am sometimes grateful to have documentary proof of just how strange it could be.

It's easy to forget, now that he's largely known as the director of middling-to-good Oscarbait, but there was a time when Clint Eastwood was at the very top of Hollywood's A-list - this was when he was still primarily an actor who occasionally dabbled in directing, mind you, and his acting consisted not of the soul-tortured apologias for his wanton, violent excesses that dominated his career from the early '90s until he retired from acting with 2008's Gran Torino; this was still the era of those very same wanton, violent, frequently nasty and misanthropic actioners, and audiences loved them all to bits. It has been said, I do not know on what evidence, that Eastwood was the biggest movie star of the 1970s.

Perhaps already beginning to tire of his Dirty Harry persona, perhaps looking to conquer new horizons, and perhaps just coked out of his mind*, Eastwood took his first major career detour, when he starred in Every Which Way But Loose, a movie written (it is said) for Burt Reynolds, another major star of that time whose career was miles away from Eastwood's. On the one hand: nihilistic cops and cowboys, meting out justice with an icy, even despotic hand. On the other: a grinning, mustached good ol' boy. There is no doubt about the fact that EWWBL feels a hell of a lot more like a Reynolds movie than it feels like anything else in Eastwood's career (except for its own sequel, Any Which Way You Can), what with its aimless, easygoing truck-driving protagonist, its country & Western soundtrack, its slapstick fistfights, it's beer-drinking orangutan.

Yes! A beer-drinking juvenile orangutan named Clyde (the ape actor's name was Manis), and this detail is likely the only reason the film has remained whatsoever current in the popular imagination. "The movie where Clint Eastwood horned in on Burt Reynolds's territory by playing a street-fighting truck driver" would appeal to a much smaller audience of Eastwood completists than would "The movie with Clint Eastwood and an orangutan". I think you don't need to be an Eastwood fan - I think you could out and out hate the man's movies - and still be at least a little bit intrigued by the very perversity of that scenario. And maybe that's the reason for the film's success, or maybe it's testament to just how unthinkably popular Eastwood was in '78 (his kind of box-office popularity literally does not exist in this day and age) that EWWBL ended up as the second-highest-grossing film of the year, behind Superman. For good or ill, we simply do not live in the same kind of world as they did back then.

Clint and an orangutan; that's as good a way to describe the movie as anything, for all the plot it has. In fact, for a solid half-hour - or about a quarter of the total running time - you could be forgiven for doubting that EWWBL had a story at all. It has, instead, scenes in the life of Eastwood's Philo Beddoe, a laid-back sort of man living in Los Angeles, making a living as a bare-knuckle brawler, living with his buddy Orville (Geoffrey Lewis), and Orville's ancient mother, Ma (Ruth Gordon). And Clyde, whom Philo won as part of one fight or another. Philo fights some folks, pisses off a local biker gang, the Black Widows, and falls head over heels for a bar singer, Lynn Halsey-Taylor (Sondra Locke, Eastwood's real-life lover at the time, and his co-star in six separate movies, of which this was the third). It's only when Lynn seemingly evaporates that EWWBL finally decides that watching Philo poking about, being easygoing and laid-back, isn't going to support an entire feature, and so the rudiments, and rudiments only, of a plot begin to kick in. Philo, Clyde and Orville head off to Denver, the only lead they have to Lynn's possible whereabouts, followed by the Black Widows and a pair of pissed-off cops; along the way, Orville falls in love with a girl much younger than he is, the hippie-named Echo (Beverly D'Angelo), though this changes very little other than adding one more voice to the bantering in the truck.

I have now used both "easygoing" and "laid-back" twice apiece, and if I wanted to look any more closely at the film's plot, I'd be obliged to use them over and over again, because EWWBL is almost aggressively modest in its charms and scope. Jokin', fightin', boozin', truckin' - the movie is about simple, working-class things, and it practically forbids you from adding -g to the end of words. It is as conservative - socially and aesthetically - as anything in the famously conservative career of its star. If I were going to be in a judgy mood, I'd call it "redneck", and given the whole Reynold's connection, plus the countrified soundtrack, it's not very daring to wonder if the film might be best fit into the hicksploitation cycle of that decade, disguised only by a flimsy urban setting.

The film is decidedly unsophisticated, not that it's exactly the same thing - it was directed by James Fargo, only lately graduated from the ranks of assistant directors, and a man of profoundly unmemorable visual style - and if there were nothing about it other than the casually dismissive way it treats its women, that would still be enough: Echo is just a flirty sexpot, Ma is just the nutty comic relief who can't drive a car, and Lord, I'd almost rather not think about Lynn, and the heavily sexist way she's disposed of at the end, having outlived her usefulness as a story element. I'd add the film's open mockery of her dreams to make it big as a singer, but then I recall that Eastwood was in love at the time, and perhaps he didn't mean for us to take her wobbly voice as badly as I, at least, did.

All of this - the indifferent direction, the sexism, the blandly reductive "it's fun to watch a guy get in fistfights in lieu of any real narrative" structure (although, that ends up being the film's structure, in an off-kilter way; the climax, and the wrapping-up of Philo's character arc that we didn't even realise existed until that moment, have to do with the big final fight, and not with his chasing Lynn at all) - make certain that EWWBL is not a "good" movie, and the fact that it was greeted with some dismay by the critics of 1978 surprises me not at all. I cannot, however, keep myself from feeling that time has been oddly kind to the movie. As John Huston purred in Chinatown, a slightly older movie that captured the Zeitgeist in a very different way, "Politicians, ugly buildings, and whores all get respectable if they last long enough". And, we might add, bad movies; maybe that's just me. At any rate, compared to a lot of the late-'70s pictures it resembles, EWWBL is just weird enough to work as a fun time capsule in a half-baked sort of way. Maybe it's the spectacle of seeing Eastwood in a mostly straight-up comedy, something as rare now as it was then. Certainly, it's the orangutan; though Clyde ends up being in the movie a lot less than you'd anticipate, given how large he looms in the film's legend (such as it is).

I think it's because he's there in such a matter-of-fact way. A little bit of dialogue to explain things without actually explaining them, and off we go: nobody seems to regard it as noteworthy that Phil travels everywhere with the little hominid, and it takes barely any time at all until Clyde just seems to be another one of the characters, getting in scrapes and getting out of them using his fists and his wit, lucky that all of the antagonists in the movie have the intelligence of damp newsprint. This unresolved strangeness is both part of the movie's magnificently relaxed charm, and something of a challenge to our suspension of disbelief: "Yeah, there's a fucking ape", it seems to say, "and you just have to deal with that. So deal".

The result is that the movie has just enough warp to it that it's interesting in despite of itself, a bizarre missive from another era when beer-drinking orangutans were all in good fun and not kind of off-putting. That's probably not the best reason to watch a movie, and yet it's what kept coming up to me, over and over, as I watched the film: people were absolutely in love with this movie once, and not such a long time ago, and that is amazing to think about. The past is a very weird place, and I am sometimes grateful to have documentary proof of just how strange it could be.