Blockbuster History: The world of Robert E. Howard

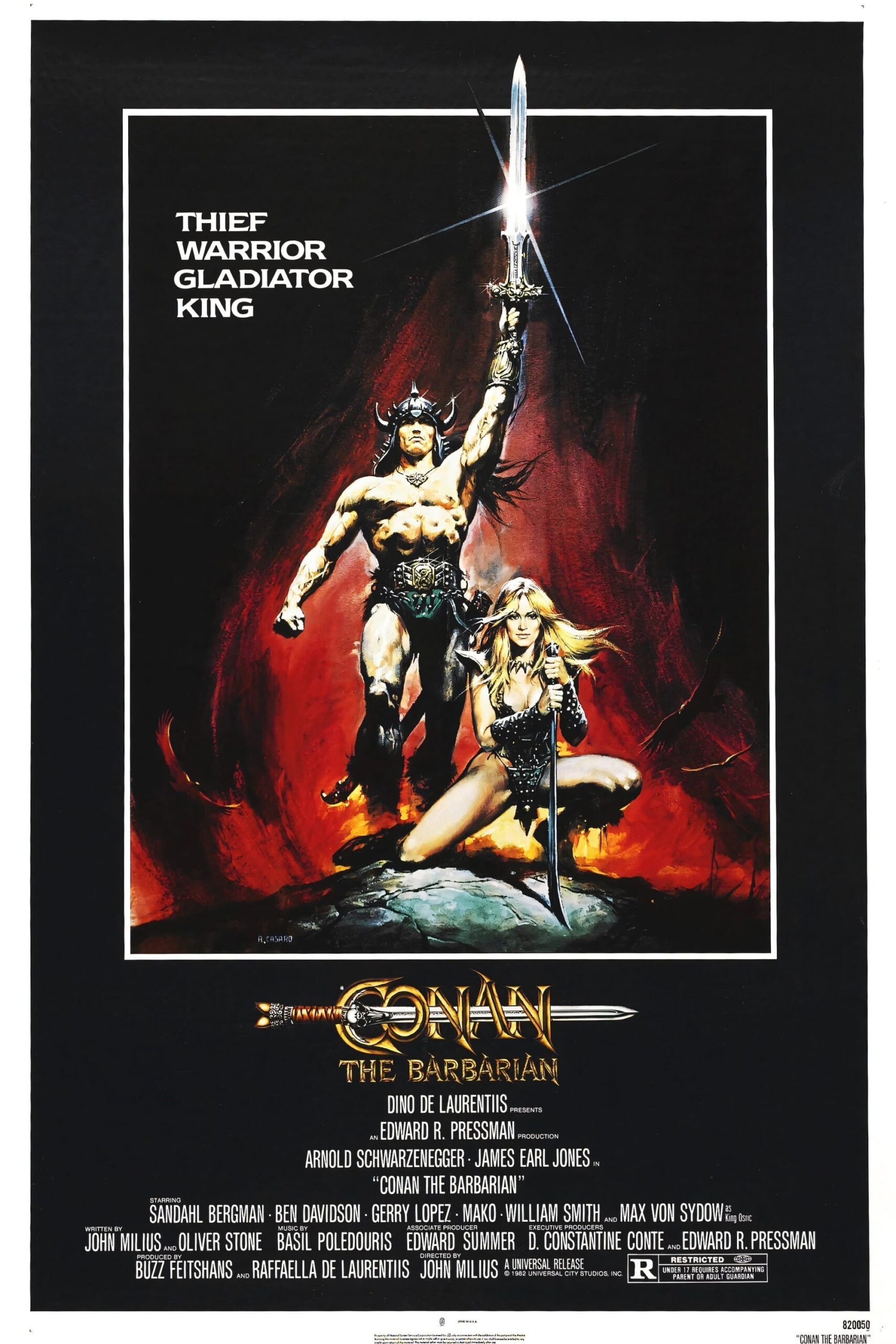

Every Sunday this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: the remake of Conan the Barbarian introduces a new generation to the pop hero of Weird Tales, one of the most durable fictional characters of the 1930s. This is not, of course, the first time Conan has been seen in film, nor the first time he's been portrayed by a mostly unknown, muscle-bound actor.

It is easy to assume that Arnold Schwarzenegger is the man primarily responsible for whatever value there is in the 1982 film Conan the Barbarian, but this is wrong. Aye, the Austrian bodybuilder, in the role that shot him to stardom from out of nothing in the blink of an eye, is such a perfect fit for the character that it's quite impossible to imagine the same film being made without him. But he's not the most indispensable figure in the film's production history.

That would instead be Basil Poledouris, who composed the score. Conan the Barbarian, as I trust you can guess even if you have not seen it, even if you know nothing but the title, is a retrograde adolescent fantasy about a physically indestructible hero using swords to kill all kinds of people in all kinds of ways in between bouts of making out with his hot barbarian girlfriend. It is a film that only wants to be described by the single adjective "awesome", though "epic" would do in a pinch. It is a film whose effectiveness, if it is to be effective at all, lies in keeping the audience constantly at a fever pitch of adrenaline, gawping at the crudely enthusiastic spectacle.

It is, however, also a film which sees a significant percentage of its running time given over to scenes of people running, riding, striding, crawling, or otherwise achieving motion through the landscapes of a mythical pre-medieval world of mountains and fields, obligingly portrayed by Andalusia. And a film, moreover, in which the lead actor was perhaps literally incapable of speaking the English language in any meaningful way when the thing was produced. Between these two things, that results in a movie with quite a few passages during which nobody says anything and nothing happens, primarily in the first half, and this is altogether not the sort of thing that anybody is likely to call "awesome" unironically.

Enter Poledouris, a man whose previous and subsequent career doesn't do much to show him off as a Talent To Notice, but it doesn't have to: with Conan the Barbarian, he became immortal (if nothing else, the choicest bits were recycled in other trailers for I don't even know how many years afterward - maybe they still are). Poledouris's score isn't just awesome, it is possible the most awesome ever. It is everything any 12-year-old has ever daydreamed about sword-and-sorcery fantasy distilled into music, a preposterously dramatic mixture of thundering beats and screaming woodwinds. If you stuffed Mussorgsky, Wagner, Carmina Burana, and the Requiem Mass into a blender, it might be nearly as blasting and portentous as this score. It is the most anti-subtle music that I think I have ever heard, and it is impossible to avoid being completely smothered and overwhelmed and swept up by the sheer insane grandeur of it. At least, if you could avoid it, you're not likely to be a person who'd voluntarily watch Conan the Barbarian.

And here's why this is all so necessary: if you are watching an activity, any activity, with Poledouris's God-smashing music playing, you will be absolutely struck by how thrilling that activity looks. There are shots of Schwarzenegger doing literally nothing but trotting through tall grass, but by God, in that moment trotting through tall grass looks peerlessly masculine. The opening credits involving a sword being forged in the tiny barbarian village where Conan was born, and between the music and the pornographically lingering shots of smoldering metal, it's enough to convince a body that sword-smithing is the pinnacle achievement of humanity.

This is how it must be - I will not say "should", because it's definitely an open question whether Conan the Barbarian "should" exist at all. The film is unapologetically immature in its views of nearly everything: women, warfare, violence, snakes. Its worldview is expressed in a line of dialogue delivered by Conan's father (William Smith) early on: "No one in this world can you trust. Not men, not women, not beasts. This you can trust". In which "this" is the sword he's just finished crafting. This is a moment delivered without shame or the mildest hint of camp - it's hard to imagine, in fact, how a film so devoted to the objectification of the male body could be this anti-campy, but that's director John Milius for you: between this and the later Red Dawn, he might well be the most aggressively sincere purveyor of the most reductive view towards the glories of combat that the 1980s have to offer. The movie he wrote (alongside Oliver Stone, another fellow with as you might say, a distinctly chauvinistic worldview) is breathtakingly free of any kind of self-reflection or mirthfulness: it is a paean to destroying everything to prove that one is the most manly of all men.

I will admit to having only cursory exposure to the Conan stories written in the 1930s by Robert E. Howard, and thus I can't say that this is true at all to the character; but the pulp fiction of that era has a certain unmissable tendency to be somewhat regressive about violence and gender issues. I don't think for a moment Milius and Stone were deliberately trying to recapture the sensibilities of a bygone era; I think that's genuinely how they thought, at least Milius did (Stone's contributions to the project being watered-down, anyway). Life would be better if we could all just mow down the bad guys with a sword.

That is, to put it mildly, an eyebrow-raising philosophy, but the movie works in despite of that: Milius's exorbitantly serious visuals, alongside Poledouris's score, are simply too damn rousing not to be swept up in the moment. Conan the Barbarian is a morally bankrupt movie, and it is at times a willfully stupid and silly movie, but it is, more than that, a damnably persuasive movie. It really shouldn't be: the plot is a hacked-together patchwork quilt of notions about life in a fantasy world, in which the main plot isn't revealed until well more than 40 minutes in, after we've already been subjected to a puzzling sequence that establishes Conan's life story, from slave to gladiator to thief, without bothering to make much sense in the incidental details. Even after that, the plot can't make up its mind to get going until it's almost too late. There's only one credible character and performance in the whole movie: James Earl Jones as Thulsa Doom (I believe I mentioned that the film is silly?), a petty warlord who turns himself into a charismatic religious leader and has just enough holes in his backstory that we get to imagine any number of terribly compelling things about him, while Jones makes sure to play him not as an outrageously evil villain but as a largely satisfied warrior turned politician. Otherwise it's Sandahl Bergman, in the horribly thankless role of the love interest in a movie written at the maturity level of a barely-pubescent boy, sounding and looks like she stopped into the studio on her way back from a suburban shopping mall, and a steady-handed pro like Mako foundering as the wacky Asian comic relief in a film that has absolutely no sense of humor. Schwarzenegger is a special case: he's objectively terrible, but the character as written is such a shallow cartoon that it would unquestionably make the film worse to have even a slightly better performance: as it is, Schwarzenegger nestles into everything which makes Conan the most ridiculous, which is also what makes him the most fun.

The film ought to suck. Even while you're watching it, there's a nagging feeling that it's all very tacky. And yet it believes in itself so very much, and has such courage in its convictions, and you absolutely cannot fake that sort of thing. When we first see Conan all grown up, in a nifty scene that shows how he alone of the little slave boys survived and turned into a huge mountain of muscles, turning a giant wheel that doesn't obviously serve a purpose; when Milius slides into his first close-up of Schwarzenegger's angry brow, as Poledouris has a musical orgasm, it's thrilling, because the film does not care about our opinion. It cares only about pleasing itself. By all means, this is crass and tacky: the geysers of blood, the unimaginative leering at naked women, the elevation of self-serving violent acts to religious status (literally - the film has a surprisingly well-developed idea about the role of religion in daily life, which boils down to: "It's fine to believe in God or gods or whatever, but don't count on those bastards for anything". There's even a famous speech near the end with almost that exact sentiment being lovingly manhandled by a parody of an Austrian). But it's boldly and bravely crass. And the result is so colorfully bad that it ceases to be bad at at all: just dazzling in its tawdriness and weirdness, collapsing irony and sincerity in upon each other so that it becomes impossible to tell if one is laughing at the movie's juvenile excesses, or with them.

It is easy to assume that Arnold Schwarzenegger is the man primarily responsible for whatever value there is in the 1982 film Conan the Barbarian, but this is wrong. Aye, the Austrian bodybuilder, in the role that shot him to stardom from out of nothing in the blink of an eye, is such a perfect fit for the character that it's quite impossible to imagine the same film being made without him. But he's not the most indispensable figure in the film's production history.

That would instead be Basil Poledouris, who composed the score. Conan the Barbarian, as I trust you can guess even if you have not seen it, even if you know nothing but the title, is a retrograde adolescent fantasy about a physically indestructible hero using swords to kill all kinds of people in all kinds of ways in between bouts of making out with his hot barbarian girlfriend. It is a film that only wants to be described by the single adjective "awesome", though "epic" would do in a pinch. It is a film whose effectiveness, if it is to be effective at all, lies in keeping the audience constantly at a fever pitch of adrenaline, gawping at the crudely enthusiastic spectacle.

It is, however, also a film which sees a significant percentage of its running time given over to scenes of people running, riding, striding, crawling, or otherwise achieving motion through the landscapes of a mythical pre-medieval world of mountains and fields, obligingly portrayed by Andalusia. And a film, moreover, in which the lead actor was perhaps literally incapable of speaking the English language in any meaningful way when the thing was produced. Between these two things, that results in a movie with quite a few passages during which nobody says anything and nothing happens, primarily in the first half, and this is altogether not the sort of thing that anybody is likely to call "awesome" unironically.

Enter Poledouris, a man whose previous and subsequent career doesn't do much to show him off as a Talent To Notice, but it doesn't have to: with Conan the Barbarian, he became immortal (if nothing else, the choicest bits were recycled in other trailers for I don't even know how many years afterward - maybe they still are). Poledouris's score isn't just awesome, it is possible the most awesome ever. It is everything any 12-year-old has ever daydreamed about sword-and-sorcery fantasy distilled into music, a preposterously dramatic mixture of thundering beats and screaming woodwinds. If you stuffed Mussorgsky, Wagner, Carmina Burana, and the Requiem Mass into a blender, it might be nearly as blasting and portentous as this score. It is the most anti-subtle music that I think I have ever heard, and it is impossible to avoid being completely smothered and overwhelmed and swept up by the sheer insane grandeur of it. At least, if you could avoid it, you're not likely to be a person who'd voluntarily watch Conan the Barbarian.

And here's why this is all so necessary: if you are watching an activity, any activity, with Poledouris's God-smashing music playing, you will be absolutely struck by how thrilling that activity looks. There are shots of Schwarzenegger doing literally nothing but trotting through tall grass, but by God, in that moment trotting through tall grass looks peerlessly masculine. The opening credits involving a sword being forged in the tiny barbarian village where Conan was born, and between the music and the pornographically lingering shots of smoldering metal, it's enough to convince a body that sword-smithing is the pinnacle achievement of humanity.

This is how it must be - I will not say "should", because it's definitely an open question whether Conan the Barbarian "should" exist at all. The film is unapologetically immature in its views of nearly everything: women, warfare, violence, snakes. Its worldview is expressed in a line of dialogue delivered by Conan's father (William Smith) early on: "No one in this world can you trust. Not men, not women, not beasts. This you can trust". In which "this" is the sword he's just finished crafting. This is a moment delivered without shame or the mildest hint of camp - it's hard to imagine, in fact, how a film so devoted to the objectification of the male body could be this anti-campy, but that's director John Milius for you: between this and the later Red Dawn, he might well be the most aggressively sincere purveyor of the most reductive view towards the glories of combat that the 1980s have to offer. The movie he wrote (alongside Oliver Stone, another fellow with as you might say, a distinctly chauvinistic worldview) is breathtakingly free of any kind of self-reflection or mirthfulness: it is a paean to destroying everything to prove that one is the most manly of all men.

I will admit to having only cursory exposure to the Conan stories written in the 1930s by Robert E. Howard, and thus I can't say that this is true at all to the character; but the pulp fiction of that era has a certain unmissable tendency to be somewhat regressive about violence and gender issues. I don't think for a moment Milius and Stone were deliberately trying to recapture the sensibilities of a bygone era; I think that's genuinely how they thought, at least Milius did (Stone's contributions to the project being watered-down, anyway). Life would be better if we could all just mow down the bad guys with a sword.

That is, to put it mildly, an eyebrow-raising philosophy, but the movie works in despite of that: Milius's exorbitantly serious visuals, alongside Poledouris's score, are simply too damn rousing not to be swept up in the moment. Conan the Barbarian is a morally bankrupt movie, and it is at times a willfully stupid and silly movie, but it is, more than that, a damnably persuasive movie. It really shouldn't be: the plot is a hacked-together patchwork quilt of notions about life in a fantasy world, in which the main plot isn't revealed until well more than 40 minutes in, after we've already been subjected to a puzzling sequence that establishes Conan's life story, from slave to gladiator to thief, without bothering to make much sense in the incidental details. Even after that, the plot can't make up its mind to get going until it's almost too late. There's only one credible character and performance in the whole movie: James Earl Jones as Thulsa Doom (I believe I mentioned that the film is silly?), a petty warlord who turns himself into a charismatic religious leader and has just enough holes in his backstory that we get to imagine any number of terribly compelling things about him, while Jones makes sure to play him not as an outrageously evil villain but as a largely satisfied warrior turned politician. Otherwise it's Sandahl Bergman, in the horribly thankless role of the love interest in a movie written at the maturity level of a barely-pubescent boy, sounding and looks like she stopped into the studio on her way back from a suburban shopping mall, and a steady-handed pro like Mako foundering as the wacky Asian comic relief in a film that has absolutely no sense of humor. Schwarzenegger is a special case: he's objectively terrible, but the character as written is such a shallow cartoon that it would unquestionably make the film worse to have even a slightly better performance: as it is, Schwarzenegger nestles into everything which makes Conan the most ridiculous, which is also what makes him the most fun.

The film ought to suck. Even while you're watching it, there's a nagging feeling that it's all very tacky. And yet it believes in itself so very much, and has such courage in its convictions, and you absolutely cannot fake that sort of thing. When we first see Conan all grown up, in a nifty scene that shows how he alone of the little slave boys survived and turned into a huge mountain of muscles, turning a giant wheel that doesn't obviously serve a purpose; when Milius slides into his first close-up of Schwarzenegger's angry brow, as Poledouris has a musical orgasm, it's thrilling, because the film does not care about our opinion. It cares only about pleasing itself. By all means, this is crass and tacky: the geysers of blood, the unimaginative leering at naked women, the elevation of self-serving violent acts to religious status (literally - the film has a surprisingly well-developed idea about the role of religion in daily life, which boils down to: "It's fine to believe in God or gods or whatever, but don't count on those bastards for anything". There's even a famous speech near the end with almost that exact sentiment being lovingly manhandled by a parody of an Austrian). But it's boldly and bravely crass. And the result is so colorfully bad that it ceases to be bad at at all: just dazzling in its tawdriness and weirdness, collapsing irony and sincerity in upon each other so that it becomes impossible to tell if one is laughing at the movie's juvenile excesses, or with them.