Fuck you and this whole city and everyone in it

A review requested by Will Beckley, with thanks for donating to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser.

25th Hour is a great curiosity in Spike Lee's filmography: it feels, to watch it, like an extremely important and personal film to him, in which the director is unloading all his anxiety and anger and fear and God knows what from 9/11 - and how right it is that the most New York of all American film directors* would have made the most nerve-jangled of all post-9/11 films, without 9/11 showing up as a plot point, but we'll get to that - and doing it through some of the most minutely realised, naturalistic characters anywhere in his filmmography. It's also his second of only three of his films with a white protagonist (the others are 1999's Summer of Sam and the 2013 remake of Oldboy; I won't tell you that you're wrong if you want to include Inside Man, but I won't tell you that you're right, either) and the only one of those three that's any good at all. And I find that very odd; not that 25th Hour suffers from being about a white man, but nor would it suffer, and it would maybe gain a little bit more bite, from being re-written to be about an African-American man.

It doesn't matter, I suppose; just one of those peculiarities that comes along every now and then. Certainly, it doesn't keep 25th Hour from being one of the most exemplary pieces of filmmaking in Lee's estimable, if singularly inconsistent career.

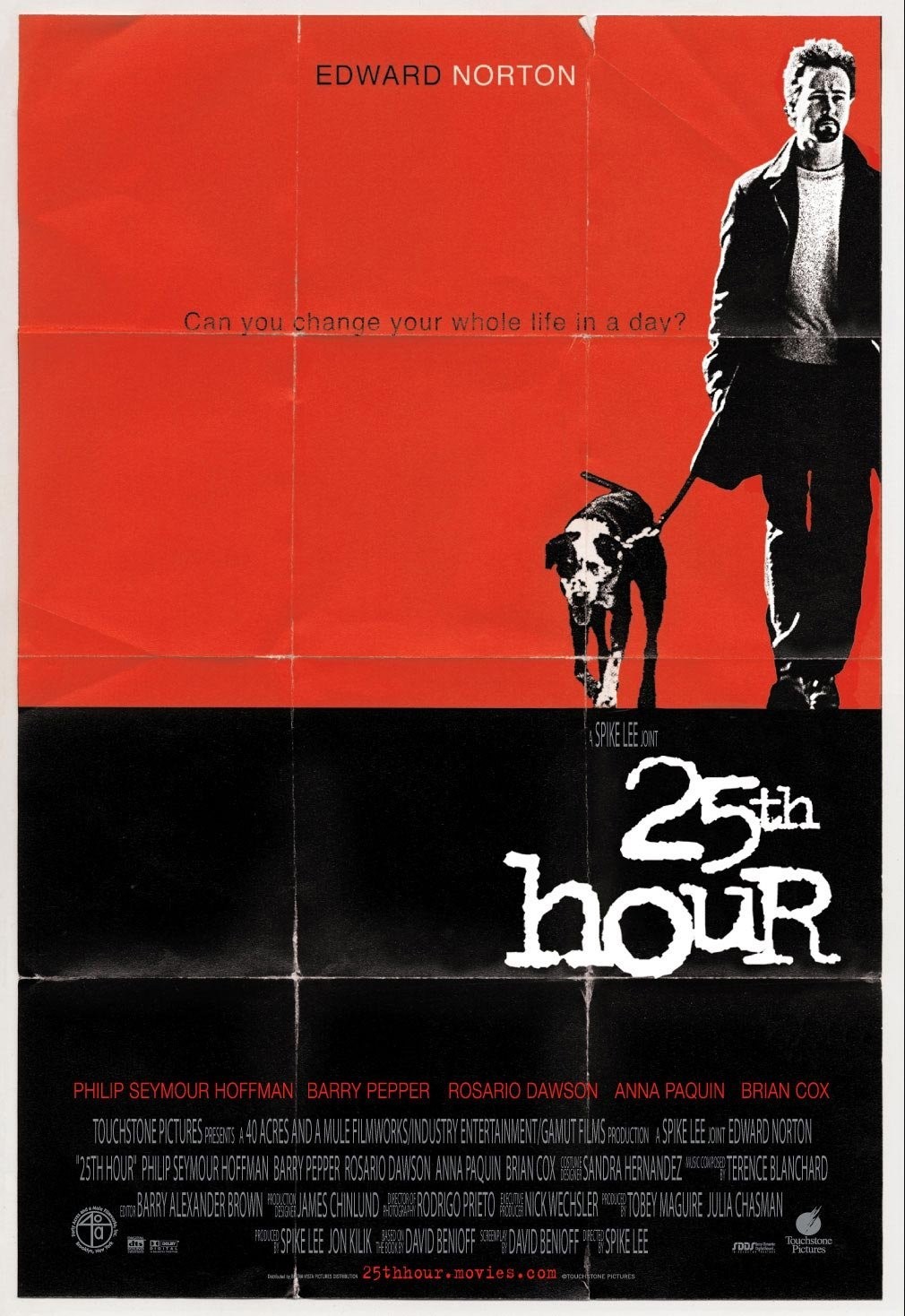

It has, if nothing else, a real barnburner of a hook. Monty Brogan (Edward Norton), 31 years old, has around 25 hours left to wander around his beloved hometown of New York, at the end of which he must report for the start of a 7-year prison sentence for possession with intent to distribute drugs. For his last day, he wants his two best friends, Wall Street hotshot Frank Slaughtery (Barry Pepper), and high school teacher Jacob Elinsky (Philip Seymour Hoffman), to party with him and his girlfriend Naturelle Riviera (Rosario Dawson). The result feels like a living wake, as Frank and Jacob, each hung up on their own problems (Frank is feeling his wings have been clipped a little bit by his boss, Jacob is trying to crush down sexual feelings for his brightest student, 17-year-old Mary D'Annunzio, played by Anna Paquin), start deliberately placing up psychological walls between themselves and their doomed friend, mournfully talking about the old days with a melancholic tone; and just to add some nastiness, Frank puts a voice behind Monty's unspoken concern that Naturelle might have been responsible for selling him out to the DEA.

The film's elegiac tone is amplified and paralleled by Lee's deep-set focus on the uncertain state of New York City in the months after the World Trade Center was destroyed in a terrorist attack. This is not a subtle theme. The opening credits, after a prologue in which Woody encounters a beaten-up dog and decides to adopt it, are against a series of shots of the New York skyline at night, with the "Tribute in Light" installation, beams of light placed in the position of the fallen towers rising into the infinity of the night sky, prominently featured in every composition. It's as direct an evocation of the idea of "the ghosts of the WTC" as it would be possible to stage, and that memory hangs heavily over the rest of the film, despite its irrelevance to the plot as such (David Benioff's novel was published before the attacks, and Benioff's screenplay does not incorporate much new material). Frank's fancy condominium, where he and Jacob have a mordant conversation about their lives moving irrevocably away from Monty's, overlooks the ruins of the WTC site, and Lee hangs on it behind their conversation in an endurance-length single static shot.

The result is a film profoundly suffused with an aura of loss, and it seems awfully clear that this aura was what drew Lee to the material in the first place. The plot is primarily about wondering what the hell happens next: Monty is stuck in the knowledge that he can no longer fix what happened in the past, and doomed to wonder how he's going to survive the future. I'm genuinely unsure if 25th Hour would prefer us to think about his personal crisis as a metaphor for rebuilding New York, or if it's the other way around; 15 years after the attacks, it's the character material that remains fresher and more immediately accessible, but the film also has a way of evoking the spirit of culture in those days in a way that e.g. Spider-Man no longer does.

Certainly, it's a very well-built character drama, with career-best performances from Norton, Pepper, and Dawson (and Hoffman's performance is every bit at the same level; he just set a much higher bar for "career-best", even as early as 2002). It's a little bit too conspicuously "made", compare to the best masterpieces of Lee's career; the kind of film where I, at least, have the response "Norton's portrayal of quiet self-loathing is tremendous" rather than "Monty's plight moves me". But it's well-made, one of the most technically confident American films of the early 2000s. Certainly Terence Blanchard's outstanding musical score belongs in any conversation about the best movie scores of that decade: the composer turns down the jazz influences in favor of more classical motifs, though the improvisational, intuitive elements remain in his use of ethnic musics tropes - mostly Middle Eastern, Russian, and Irish flavoring.

It's also an amazing piece of cinematography and editing, courtesy of Rodrigo Prieto and Barry Alexander Brown, respectively. This was right at the height of Prieto's post-Amores perros prominence as one of the world's most exciting cinematographers, and it might very well be the best work he ever committed to celluloid (and man alive, if you want to see a movie that'll make you despair for the digital-and-only-digital world we've almost complete moved into, 25th Hour will do it). The baseline of over-saturated, grainy footage that represents "here and now" is already some of the most effective urban cinematography of its generation, refusing to make New York's streets and buildings look "pretty" as such, by capturing with great attention the dirt and grit and texture of everything we see. But the potency of the colors do get at something magical, suggesting Monty's (and Spike Lee's) romantic attachment to the city even despite its grossness and flaws, particularly right on the verge of losing that city for the next seven years.

The really showy tricks, a Prieto specialty, are reserved for the "out of time" moments: Monty's raging denunciation of every ethnic and class group he can think of sharing space in New York (present in Benioff's novel, but in the film it feels too much like a desperate, overcooked redo of the "Racial Slur Montage" from Lee's Do the Right Thing, without the pungency of that film's social critique), and his fathers' (Brian Cox) increasingly feverish, passionate narrative of how Monty might escape his fate by fleeing into the boundless American West, with the harshness of the lighting and unreality of the colors increasing as the story progresses further into the imagined future. And that's as good a place as any to drag Brown into it, since the clipped editing of the montages is merely an extension of how the whole feature has been cut: more as a series of ellipses, assembling scenes from slightly discontinuous fragments to create a powerful sense of time slipping past without us quite being able to clock it; this only changes once the film arrives at the nightclub where Monty finally stares his feelings in the face (as does Jacob, in a scene that gives Hoffman plenty to work with, though I'm not sure the film actually benefits from having it). And this is above and beyond the macro-structure, in which the film blurs flashbacks with present tense scenes according to a fairly obvious logic - what is Monty thinking and feeling right now? - that never feels particularly schematic in practice.

It's a marvelous machine, 25th Hour is; impeccably conceived and fashioned. I've never quite been able to bring myself to join in the "one of the great films of the 2000s" hosannas that the film has enjoyed over the years; it feels like Lee is keeping it all at arm's length, for reasons I can't quite figure out. Still, this is certainly a great piece of film craftsmanship, a film of handsome ugliness in both its aesthetic and its willingness to examine human misery in a tightly-controlled space. In many ways, it's Lee's most impressive film of the 21st Century; certainly, it is his most focused and deliberate. It's dour as hell and the running time is not swift (it's just shy of two and a quarter hours long), but this film's status as one of the key American films of the early years of the millennium is simply beyond question.

*After Woody Allen, perhaps, but can you even remotely fathom such a thing as a Woody Allen 9/11 film vomiting its way into the world?

25th Hour is a great curiosity in Spike Lee's filmography: it feels, to watch it, like an extremely important and personal film to him, in which the director is unloading all his anxiety and anger and fear and God knows what from 9/11 - and how right it is that the most New York of all American film directors* would have made the most nerve-jangled of all post-9/11 films, without 9/11 showing up as a plot point, but we'll get to that - and doing it through some of the most minutely realised, naturalistic characters anywhere in his filmmography. It's also his second of only three of his films with a white protagonist (the others are 1999's Summer of Sam and the 2013 remake of Oldboy; I won't tell you that you're wrong if you want to include Inside Man, but I won't tell you that you're right, either) and the only one of those three that's any good at all. And I find that very odd; not that 25th Hour suffers from being about a white man, but nor would it suffer, and it would maybe gain a little bit more bite, from being re-written to be about an African-American man.

It doesn't matter, I suppose; just one of those peculiarities that comes along every now and then. Certainly, it doesn't keep 25th Hour from being one of the most exemplary pieces of filmmaking in Lee's estimable, if singularly inconsistent career.

It has, if nothing else, a real barnburner of a hook. Monty Brogan (Edward Norton), 31 years old, has around 25 hours left to wander around his beloved hometown of New York, at the end of which he must report for the start of a 7-year prison sentence for possession with intent to distribute drugs. For his last day, he wants his two best friends, Wall Street hotshot Frank Slaughtery (Barry Pepper), and high school teacher Jacob Elinsky (Philip Seymour Hoffman), to party with him and his girlfriend Naturelle Riviera (Rosario Dawson). The result feels like a living wake, as Frank and Jacob, each hung up on their own problems (Frank is feeling his wings have been clipped a little bit by his boss, Jacob is trying to crush down sexual feelings for his brightest student, 17-year-old Mary D'Annunzio, played by Anna Paquin), start deliberately placing up psychological walls between themselves and their doomed friend, mournfully talking about the old days with a melancholic tone; and just to add some nastiness, Frank puts a voice behind Monty's unspoken concern that Naturelle might have been responsible for selling him out to the DEA.

The film's elegiac tone is amplified and paralleled by Lee's deep-set focus on the uncertain state of New York City in the months after the World Trade Center was destroyed in a terrorist attack. This is not a subtle theme. The opening credits, after a prologue in which Woody encounters a beaten-up dog and decides to adopt it, are against a series of shots of the New York skyline at night, with the "Tribute in Light" installation, beams of light placed in the position of the fallen towers rising into the infinity of the night sky, prominently featured in every composition. It's as direct an evocation of the idea of "the ghosts of the WTC" as it would be possible to stage, and that memory hangs heavily over the rest of the film, despite its irrelevance to the plot as such (David Benioff's novel was published before the attacks, and Benioff's screenplay does not incorporate much new material). Frank's fancy condominium, where he and Jacob have a mordant conversation about their lives moving irrevocably away from Monty's, overlooks the ruins of the WTC site, and Lee hangs on it behind their conversation in an endurance-length single static shot.

The result is a film profoundly suffused with an aura of loss, and it seems awfully clear that this aura was what drew Lee to the material in the first place. The plot is primarily about wondering what the hell happens next: Monty is stuck in the knowledge that he can no longer fix what happened in the past, and doomed to wonder how he's going to survive the future. I'm genuinely unsure if 25th Hour would prefer us to think about his personal crisis as a metaphor for rebuilding New York, or if it's the other way around; 15 years after the attacks, it's the character material that remains fresher and more immediately accessible, but the film also has a way of evoking the spirit of culture in those days in a way that e.g. Spider-Man no longer does.

Certainly, it's a very well-built character drama, with career-best performances from Norton, Pepper, and Dawson (and Hoffman's performance is every bit at the same level; he just set a much higher bar for "career-best", even as early as 2002). It's a little bit too conspicuously "made", compare to the best masterpieces of Lee's career; the kind of film where I, at least, have the response "Norton's portrayal of quiet self-loathing is tremendous" rather than "Monty's plight moves me". But it's well-made, one of the most technically confident American films of the early 2000s. Certainly Terence Blanchard's outstanding musical score belongs in any conversation about the best movie scores of that decade: the composer turns down the jazz influences in favor of more classical motifs, though the improvisational, intuitive elements remain in his use of ethnic musics tropes - mostly Middle Eastern, Russian, and Irish flavoring.

It's also an amazing piece of cinematography and editing, courtesy of Rodrigo Prieto and Barry Alexander Brown, respectively. This was right at the height of Prieto's post-Amores perros prominence as one of the world's most exciting cinematographers, and it might very well be the best work he ever committed to celluloid (and man alive, if you want to see a movie that'll make you despair for the digital-and-only-digital world we've almost complete moved into, 25th Hour will do it). The baseline of over-saturated, grainy footage that represents "here and now" is already some of the most effective urban cinematography of its generation, refusing to make New York's streets and buildings look "pretty" as such, by capturing with great attention the dirt and grit and texture of everything we see. But the potency of the colors do get at something magical, suggesting Monty's (and Spike Lee's) romantic attachment to the city even despite its grossness and flaws, particularly right on the verge of losing that city for the next seven years.

The really showy tricks, a Prieto specialty, are reserved for the "out of time" moments: Monty's raging denunciation of every ethnic and class group he can think of sharing space in New York (present in Benioff's novel, but in the film it feels too much like a desperate, overcooked redo of the "Racial Slur Montage" from Lee's Do the Right Thing, without the pungency of that film's social critique), and his fathers' (Brian Cox) increasingly feverish, passionate narrative of how Monty might escape his fate by fleeing into the boundless American West, with the harshness of the lighting and unreality of the colors increasing as the story progresses further into the imagined future. And that's as good a place as any to drag Brown into it, since the clipped editing of the montages is merely an extension of how the whole feature has been cut: more as a series of ellipses, assembling scenes from slightly discontinuous fragments to create a powerful sense of time slipping past without us quite being able to clock it; this only changes once the film arrives at the nightclub where Monty finally stares his feelings in the face (as does Jacob, in a scene that gives Hoffman plenty to work with, though I'm not sure the film actually benefits from having it). And this is above and beyond the macro-structure, in which the film blurs flashbacks with present tense scenes according to a fairly obvious logic - what is Monty thinking and feeling right now? - that never feels particularly schematic in practice.

It's a marvelous machine, 25th Hour is; impeccably conceived and fashioned. I've never quite been able to bring myself to join in the "one of the great films of the 2000s" hosannas that the film has enjoyed over the years; it feels like Lee is keeping it all at arm's length, for reasons I can't quite figure out. Still, this is certainly a great piece of film craftsmanship, a film of handsome ugliness in both its aesthetic and its willingness to examine human misery in a tightly-controlled space. In many ways, it's Lee's most impressive film of the 21st Century; certainly, it is his most focused and deliberate. It's dour as hell and the running time is not swift (it's just shy of two and a quarter hours long), but this film's status as one of the key American films of the early years of the millennium is simply beyond question.

*After Woody Allen, perhaps, but can you even remotely fathom such a thing as a Woody Allen 9/11 film vomiting its way into the world?