John Hughes Retrospective: Not as bright as your eyes tonight

"Samantha Baker is turning sixteen and she’s fallen in love for the first time. It should be the best time of her life.The copy on the poster for Sixteen Candles does not, at any rate, leave much room for the imagination. In this respect, it is pairs well with the film it advertises, for Sixteen Candles is that kind of movie that announces itself early on as being more concerned with observation than with cleverness. Even allowing that in 1984, the high school film had not become as obvious as it would eventually - allowing, further, that Sixteen Candles was one of the key moments in the development of the contemporary high school film if not the primary text for the whole genre - writer John Hughes would not appear terribly concerned with challenging the viewer, so much as he is allowing us to follow along on an exploration of a theme, setting a cluster of characters and events in motion to see what happens.

"But... her family is so preoccupied with her sister’s wedding they totally forget her birthday, the boy she loves doesn’t know she exists and the class clown is putting the make on her.

"And... she still has to go to school, ride the bus, put up with an annoying younger brother, a hopelessly vain older sister, four delirious grandparents and a whacked-out foreign exchange student.

"Well, hang in there, Samantha. The day’s not over yet. You may still get one wish."

I'm sorry, writer-director John Hughes. After the success of Mr. Mom and Vacation, he was finally given the keys, as it were, and the result was the first thing we would be inclined, in hindsight, to call a "John Hughes" movie: a music-heavy comedy with just a light swirl of the serious and the adult that treats the matter of high school and high schoolers with a particular gravity and respect, though from a distinct outsider's perspective.

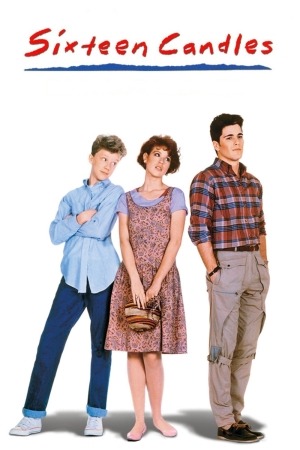

The plot- oh, but the poster already did the plot for me, didn't it? Anyway, Sam is played by Molly Ringwald, who became in an eyeblink the Face Of Her Generation when the movie came out, and for a little while got all the good roles and even worked with fucking Jean-Luc Godard. She's a sophomore, it's the day of a school dance (which is theoretically meant to be prom, I think, but forgive my ignorance: do sophomores get to attend prom?), and she is, as mentioned, newly sixteen, and confused as hell about that means. She is desperately infatuated with senior Jake Ryan (Michael Schoeffling), who is dating the class bitch Caroline Mulford (Haviland Morris); she is meanwhile fending off the advances of the Geek (Anthony Michael Hall), a freakishly awkward freshman.

Like all of Hughes's scripts to that point, Sixteen Candles is largely about what fills in the spaces in between the story, and like all of them, that filling is largely broad-strokes comic interludes in which realistic-ish characters get involved in wacky episodes. What makes it unique in his canon is that it doesn't have even the fig leaf of a driving conflict as did Mr. Mom (learning how to take care of a house) and Vacation (getting to Walley World). Sam's disconnect from her family is barely used even as a crutch in the 93-minute film's middle third, and it's resolved around the one-hour mark; her crush on Jake is presented more as a situation than as a dramatic force. In effect, Sixteen Candles tells us what the background is for the main character, and then proceeds to go through a single night, morning, and afternoon of her life, stopping along the way to pay attention to the events that occur to the people around her in that time. Structurally, it's most similar to Class Reunion out of Hughes's scripts, though with the significant difference that its characters are not parodies or grotesques. Not mostly, anyway, as there are some key exceptions.

In short, Hughes seemed to be aware even before he started that he had a reputation as a chronicler of high school sociology to maintain; for in essence, that is all that Sixteen Candles does, and all it aims to do. The problem Sam is made to overcome is not, as we might expect, that her parents are idiots, her siblings annoyances, and her grandparents gargoyles. Nor is it that she can't bring herself to tell Jake that she has a crush on him, and thereby learn that he has a crush on her, and that if one of them would just damn well open their mouths they'd both be happier off. Her problem is that she is a sixteen-year-old high school girl, and that is a problem which cannot be resolved in a film that only depicts a roughly 36-hour period. Two and a half decades of Hughes imitations - some of which he wrote himself - have obscured what a bold gesture this must have been in 1984, and explain why the film was so broadly celebrated despite its appearance, to contemporary eyes, as being appealing but slight and incredibly dated.

There are, broadly speaking, three films inside Sixteen Candles. First is the one I just described: the wry depiction of high school as an existential trap, told with sympathetic detachment by a man in his mid-'30s. This is much the best of the three: Ringwald is just plain terrific, for one, and that is generally the most important element in any given character study, which is basically what this amounts to (it's also the specific sub-category of character study that I personally find hardest to resist: the Long, Dark Night of the Soul, in which the protagonist learns all about her strengths and weaknesses over the course of a singularly incident-filled night. For another film that plumbs this territory and borrows liberally from Hughes in the process, see Superbad).

The second one is the teensploitation romantic comedy about Sam's farcical inability to hook up with Jake until the very end; a more typical film and undermined by Schoeffling's decidedly wobbly performance (very few of the young performers match Ringwald, or come even a little close: Anthony Michael Hall does, though it's a rough go given that the "right" performance of his character is necessarily annoying, and in a small role, John Cusack makes a huge impression and it's easy to see how this film - his second - set him on the path to bigger and brighter things, though he often fails to live up to the promise he showed here). Still, as the closest the film has to a story, it binds things together nicely.

It's the third film where things go wrong: this is the part of the film that has to do with the other characters besides Sam, the part where a charmingly brittle teen comedy turns into a boisterous R-rated comedy of stupid people (and yet the film slipped by with a PG, despite having a few precision F-bombs and a fully-naked shower scene). And, dismayingly, it's in this third movie that John Hughes, director, really shows off. For the most part, the film is directed by-the-numbers, exactly what you'd expect from a writer making his first feature. When the wacky comedy really amps up, though, that's when Hughes indulges in a love of unamusing slapstick and drunkenly obvious camera set-ups driving us to the gag, and worst of all are the sound effects, squeaks and bongs and whooshes and a Chinese motif that plays whenever the foreign exchange student is mentioned...

Undoubtedly, the worst part of Sixteen Candles, worse by far than the blowsy comedy, is Gedde Watanabe's performance as Long Duk Dong, staying with one set of Sam's grandparents, and forced into her life for the night with "comic" misadventures, which consist almost entirely of him being Asian and therefore Not Like Us. Also because he has a name which is only a breath away from "Long Duck Penis", because haha, the Chinese. There's not a single moment the character is onscreen mentioned that I wasn't cringing myself into the fetal position, and I might as well point out that in the beginning of the movie, the idea that a white girl would date a black man is treated as silly and funny on the face of it.

It's a lily-white film, all right, but there is a significant consideration to be made about the "dating a black guy? HAHA!" moment: the film is set on the North Shore of Chicago, Hughes's first long-term cinematic treatment of his beloved adolescent home (he went to high school in Northbrook not technically a North Shore community - it's not on Lake Michigan - later immortalised in his films behind the name "Shermer", though the city in which Sixteen Candles takes place is never named). And it was certainly true of the North Shore in 1984, and is largely true of it still, that it is a place where rich white people live. It is clearly not the case that Hughes is satirising the heavily conservative milieu of his characters: on the contrary, he plainly has a great deal of affection for Chicagoland, as one will; the film opens, not with any of its characters, but with Chicago radio institution Dick Biondi giving us a traffic report about I-290, the sort of detail that is local color if you don't know what the hell I'm talking about, and is a thick marker of regional pride if you do.*

But back to Sixteen Candles. It's good more than it's not: Sam is a fantastic character played beautifully, and her life is just specific enough that she can be universal without being vague. I don't know that Hughes "gets" women at this point - the cheesecake shot of a showering high school senior doesn't belong in a chick flick of any stripe - and his ability to direct comedy was incredibly immature relative to his ability to write comedy, and hence we get all of the shticky gags in all of the B-plots, a uniformly low-brow tone that is unsatisfying somehow even when it works well (as, for example, the matter of the Geek borrowing Sam's underwear to prove his manhood). It makes a good start for the Legend of John Hughes, though, a high school film just smart enough to be special and bad enough that it could be improved upon.

Categories: comedies, coming-of-age, john hughes, shot in chicago, stoopid comedies, teen movies