The 47th Chicago International Film Festival

Screen at CIFF: 10/7 & 10/8 & 10/13

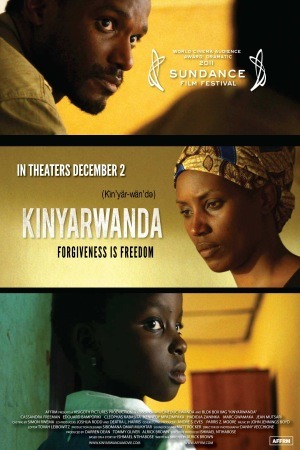

World premiere: 24 January, 2011, Sundance Film Festival

For a few horrible moments, it seems to be the case that Kinyarwanda is going to be a variant of Romeo and Juliet set during the Rwanda genocide of 1994, a notion so tacky & yet so obvious that I'm a little bit shocked nobody has thought to do it yet: Jeanne (Zaninka Hadidja) is a Tutsi, Patrique (Marc Gwamaka) is a Hutu, and they are in cutesy-pie first love, even though there are profound cultural roadblocks in their way, as demonstrated by the literal roadblock Patrique walks by while escorting Jeanne home, where he notes a cluster of Tutsis at the mercy of Hutus with machetes.

But soon enough, the movie proves what a damn idiot I was, for as Jeanne pokes around the house looking for her folks, she finds them lying dead, hacked into a bloody pile of flesh. One has just enough time to reflect that she'd have been with them if she hadn't given in to Patrique's gentle cajoling earlier in the night, before the shock cut to another time and place completely. For Kinyarwanda is not any kind of melodrama at all: it is a collection of short stories taking place in the same general region at the same time, along with a flash-forward 10 years, at which time some of the men responsible for perpetrating the Biblical amount of violence seen in the genocide were in prison camps, forced to come to terms with their actions (I will concede that although the bulk of the film was pretty great, I never got behind the 2004 material: it doesn't gel with the rest of the film at all, and even if it did, it's not nearly as compelling as Anne Aghion's 2009 documentary on the same theme, My Neighbor, My Killer. Thankfully, there is very little of it). The 1994 stories are all based in reality; writer-director Alrick Brown has reworked and recombined them into something not unlike Crash or any other hyperlink film, except without the portentous sense of irony, or anything else portentous, for that matter.

Armed with the knowledge that these are all true stories, everything seems that much more Dark and Serious, but even without that, the characters and incidents involved are quite fascinating enough, and sufficiently unlike any of the other stories to have come out of that conflict (about which, anyway, we Americans are still entirely too ignorant) that Kinyarwanda is a fresh, illuminating, and important as any other film about Rwanda that I've seen. We have the tale of Ishmael (Hassan Kabera), a toddler whose blithe innocence stands in stark, even absurd contrast to the death and violence around him (his is the only story with a comic, or at least semi-comic payoff); Lt. Rose (Cassandra Freeman), an exile returning home to use her military training to stop as much bloodshed as she can manage; and the big one, what we might call the A-plot if we felt so obliged, and certainly the most unusual and therefore necessary of Kinyarwanda's tangents, is the tale of Christian priest Father Pierre (Mazimpaka Kennedy) the so-called Father Cockroach much desired by the Hutus (the radio broadcast announcing his status as Public Enemy #1 is the first tie that binds all of the other stories together, though it is not the last). To find shelter, Pierre and his followers are obliged to seek the aid of a sympathetic Islamic mufti (Mutsari Jean), and the resultant message about religious tolerance in the face of incoherent violence and civil war is so thought-provoking that if there were not another reason for Kinyarwanda to exist, this subplot would be quite enough all on its own.

Brown guides all of this overlapping, interweaving material with a magnificently steady hand, far too confident and thoughtful for this to be his debut feature, but so it goes; it's going to be very worth seeing where he goes next, I'd wager. But sticking to the present, and to Kinyarwanda, here is a film of measured tones and a refusal to beg for our misery and gloss over history for melodramatic fireworks (there's even a jab at Hotel Rwanda, a film which does just that*), whose commitment to exploring and understanding the breadth of human experiences which were interrupted by the outbreak of violence makes it unique in the annals of movies about Rwanda. We are used to stories of individuals in this context; a story of a whole society, from the children to the priests to the soldiers, finding its way through the hell of genocide is rarer altogether (as stories about societies instead of individuals tend to be rare), and that's reason enough to call Kinyarwanda an essential film on its subject.

I could grouse about a few details here and there - the predominately non-professional cast results in the usual mixture of good performances and almost good enough performances, and the hyperlinking structure takes a bit longer to come together than it probably ought to; for at least the first 30 minutes, there is a conflict between the high quality of the individual components and the arbitrariness with which those components are assembled. It's a great film about Rwanda, not a perfect film about Rwanda, let us say; still, that Brown has found a completely new angle to approach this material from is justification all itself, and that he makes his film with self-assurance and a clear, unromantic style is enough to make Kinyarwanda essential viewing for understanding more about this particularly dark chapter of human history.

NB: the title, we are informed at the start, is the lingua franca of Rwanda, spoken by the vast majority of its citizenry; a quieter & finer way of asserting "we are all more alike than we are different" in this context, I cannot imagine.

8/10

World premiere: 24 January, 2011, Sundance Film Festival

For a few horrible moments, it seems to be the case that Kinyarwanda is going to be a variant of Romeo and Juliet set during the Rwanda genocide of 1994, a notion so tacky & yet so obvious that I'm a little bit shocked nobody has thought to do it yet: Jeanne (Zaninka Hadidja) is a Tutsi, Patrique (Marc Gwamaka) is a Hutu, and they are in cutesy-pie first love, even though there are profound cultural roadblocks in their way, as demonstrated by the literal roadblock Patrique walks by while escorting Jeanne home, where he notes a cluster of Tutsis at the mercy of Hutus with machetes.

But soon enough, the movie proves what a damn idiot I was, for as Jeanne pokes around the house looking for her folks, she finds them lying dead, hacked into a bloody pile of flesh. One has just enough time to reflect that she'd have been with them if she hadn't given in to Patrique's gentle cajoling earlier in the night, before the shock cut to another time and place completely. For Kinyarwanda is not any kind of melodrama at all: it is a collection of short stories taking place in the same general region at the same time, along with a flash-forward 10 years, at which time some of the men responsible for perpetrating the Biblical amount of violence seen in the genocide were in prison camps, forced to come to terms with their actions (I will concede that although the bulk of the film was pretty great, I never got behind the 2004 material: it doesn't gel with the rest of the film at all, and even if it did, it's not nearly as compelling as Anne Aghion's 2009 documentary on the same theme, My Neighbor, My Killer. Thankfully, there is very little of it). The 1994 stories are all based in reality; writer-director Alrick Brown has reworked and recombined them into something not unlike Crash or any other hyperlink film, except without the portentous sense of irony, or anything else portentous, for that matter.

Armed with the knowledge that these are all true stories, everything seems that much more Dark and Serious, but even without that, the characters and incidents involved are quite fascinating enough, and sufficiently unlike any of the other stories to have come out of that conflict (about which, anyway, we Americans are still entirely too ignorant) that Kinyarwanda is a fresh, illuminating, and important as any other film about Rwanda that I've seen. We have the tale of Ishmael (Hassan Kabera), a toddler whose blithe innocence stands in stark, even absurd contrast to the death and violence around him (his is the only story with a comic, or at least semi-comic payoff); Lt. Rose (Cassandra Freeman), an exile returning home to use her military training to stop as much bloodshed as she can manage; and the big one, what we might call the A-plot if we felt so obliged, and certainly the most unusual and therefore necessary of Kinyarwanda's tangents, is the tale of Christian priest Father Pierre (Mazimpaka Kennedy) the so-called Father Cockroach much desired by the Hutus (the radio broadcast announcing his status as Public Enemy #1 is the first tie that binds all of the other stories together, though it is not the last). To find shelter, Pierre and his followers are obliged to seek the aid of a sympathetic Islamic mufti (Mutsari Jean), and the resultant message about religious tolerance in the face of incoherent violence and civil war is so thought-provoking that if there were not another reason for Kinyarwanda to exist, this subplot would be quite enough all on its own.

Brown guides all of this overlapping, interweaving material with a magnificently steady hand, far too confident and thoughtful for this to be his debut feature, but so it goes; it's going to be very worth seeing where he goes next, I'd wager. But sticking to the present, and to Kinyarwanda, here is a film of measured tones and a refusal to beg for our misery and gloss over history for melodramatic fireworks (there's even a jab at Hotel Rwanda, a film which does just that*), whose commitment to exploring and understanding the breadth of human experiences which were interrupted by the outbreak of violence makes it unique in the annals of movies about Rwanda. We are used to stories of individuals in this context; a story of a whole society, from the children to the priests to the soldiers, finding its way through the hell of genocide is rarer altogether (as stories about societies instead of individuals tend to be rare), and that's reason enough to call Kinyarwanda an essential film on its subject.

I could grouse about a few details here and there - the predominately non-professional cast results in the usual mixture of good performances and almost good enough performances, and the hyperlinking structure takes a bit longer to come together than it probably ought to; for at least the first 30 minutes, there is a conflict between the high quality of the individual components and the arbitrariness with which those components are assembled. It's a great film about Rwanda, not a perfect film about Rwanda, let us say; still, that Brown has found a completely new angle to approach this material from is justification all itself, and that he makes his film with self-assurance and a clear, unromantic style is enough to make Kinyarwanda essential viewing for understanding more about this particularly dark chapter of human history.

NB: the title, we are informed at the start, is the lingua franca of Rwanda, spoken by the vast majority of its citizenry; a quieter & finer way of asserting "we are all more alike than we are different" in this context, I cannot imagine.

8/10