There are many cures for a broken heart, but nothing quite like a trout's leap in the moonlight.

Return to the complete Twin Peaks index

Written by Harley Peyton & Robert Engels

Directed by Stephen Gyllenhaal

Airdate: 18 April, 1991

Now this is how you ramp up a damn television series. With only three episodes left of Twin Peaks, mk. 1 (though at the time this one was made, I believe there was still optimism about getting a third season), Episode 27 brings us back tantalizingly close to the heights of the first half of the second season. It takes major strides to kick-off the very last run of conflicts that will animate Episodes 28 and 29, and does so while paying full attention the ominous atmosphere that used to be the show's calling card, and had been almost completely abandoned for months by the time this episode aired. Stephen Gyllenhaal (the father of the better-known acting Gyllenhaals) had been padding around directing television for ten years by the time he got his only Twin Peaks gig, doing nothing particularly noteworthy before or since, but the man deserves credit: his David Lynch impression was very much on point. This is among the best-directed episodes in the show's run, and it's a damn pity that Gyllenhaal didn't come along sooner; it's tempting to assume he might have been able to save some of the less-dodgy scripts along the way, and maybe even get a second episode under his belt before the show folded.

I think the best testament to how very damn good Episode 27 is, is that it's able to take material that very specifically has failed to work in the past, and without obviously changing anything about it, causing it to somehow be amazing. Take, for instance, the dreary matter of Windom Earle (Kenneth Welsh). Ever since we got our first really good look at Earle in the flesh, in Episode 22, the character has suffered from being enormously overhyped: the cold-blooded, merciless genius, the pure evil foil to the pure goodness of Kyle MacLachlan's Dale Cooper, has fairly consistently come off as a sniggering adolescent playing goofball pranks in between dressing up in ridiculously stupid costumes. And obviously, that could be the stuff of classic villainy - I have basically just described Batman's beloved archenemy, the Joker, have I not? - the gulf between how characters talk about Earle and how he's presented, between the solemn mood with which Twin Peaks presents evil, and the hammy way Welsh plays the character, has consistently undercut him.

And then, just like that, we get some absolutely splendid Earle this time around - consistently so, I would be willing to say. The scene where he wanders up to attack Garland Briggs (Don S. Davis) while dressed as a pantomime horse, fits squarely into the "idiot clown" side of the character's villainy, and yet it's such an unnerving, creepy scene. A lot of that is due simply to setting: an exterior scene, in the woods, in full daylight, is such an incongruous context even for a show like Twin Peaks to stage an attack. The sheer banal simplicity of the moment gives it a delirious quality missing from most of Earle's previous moments. A similar feeling attaches itself to an earlier scene, in which Briggs, Cooper, and Harry (Michael Ontkean) watch old 16mm footage of Earle, converted to VHS, babbling about the ancient rituals of a lost race, used to access the Black Lodge and celebrate its evil. The very perfunctory crappiness of the footage gives Welsh's unusually subdued performance - he's channeling a square, professorial vibe underneath the mumbling - a jolt of unreality that suits it extremely well. And even the more straightforward Earle moments, when he's just cackling with evil, seem to work better, somehow; Welsh is maybe a bit more reined-in, and Leo (Eric Da Re), fumblingly re-acquiring the humanity he never had before becoming a vegetable, makes for a strong enough contrast that Earle's villainy has more context.

Also, the final Earle scene is introduced with a shot of Leo and Briggs writhing on the ground, as the camera swirls around like a drunk housefly. That'll help with the atmosphere of anything.

Basically, Gyllenhaal is just really damn good at instilling a grim aura into everything that needs it. And we have not had that aura for ages. Even the show's incontestably worst plotline right now, the whole thing where Catherine (Piper Laurie) is trying to crack upon the surely-not-a-trap box left by the dead Thomas Eckhardt, manages to work: when Andrew (Dan O'Herlihy), a character I reliably forget exists when he's not onscreen, comes along to help his sister, his snappish tone with her is unexpected enough to feel like some nasty malevolent force has just intruded into their scene. An even better example: the early scene of Donna (Lara Flynn Boyle) examining her birth certificate and family albums in attic suffers, as the whole "did Ben actually father Donna?" plotline does, from taking too long to cover the points that the whole audience certainly ought to be able to predict. But it's so good - the action is staged directly in front of a large fan circulating air and creating a dramatic, strobe-like effect. It is, of course, a direct lift from Lynch, hardly inspired originality; but it's a good lift from Lynch, and it makes this scene shockingly tense as well as ineffably sad, and frankly, if the only good to come out of this plotline was this scene, I'd consider it worth it.

Just about the only things that I simply cannot sign off on are yet another scene between the ditsy sexpot-turned-beauty pageant cheat Lana (Robyn Lively) and her besotted ancient beau, Dwayne Milford (John Boylan), and the whole thing where Audrey (Sherilyn Fenn) tearily begs John Justice Wheeler (Billy Zane) to deflower her. The former is at least salvaged by Boylan's line readings. The latter is beyond redemption (what the hell happened to Audrey? They were doing so good at setting her up to be a sharklike business genius, and then just slammed her head-first into this godawful, vaguely pedophilic love story), despite Fenn's best efforts. But it does at least lead into a truly wonderful scene between Audrey and Pete (Jack Nance), the first time these characters have been thrown together as I recall, in which he gently offers to take her fishing, in the most kindly, grandfatherly tones. It's a terrific moment for two of the show's best actors.

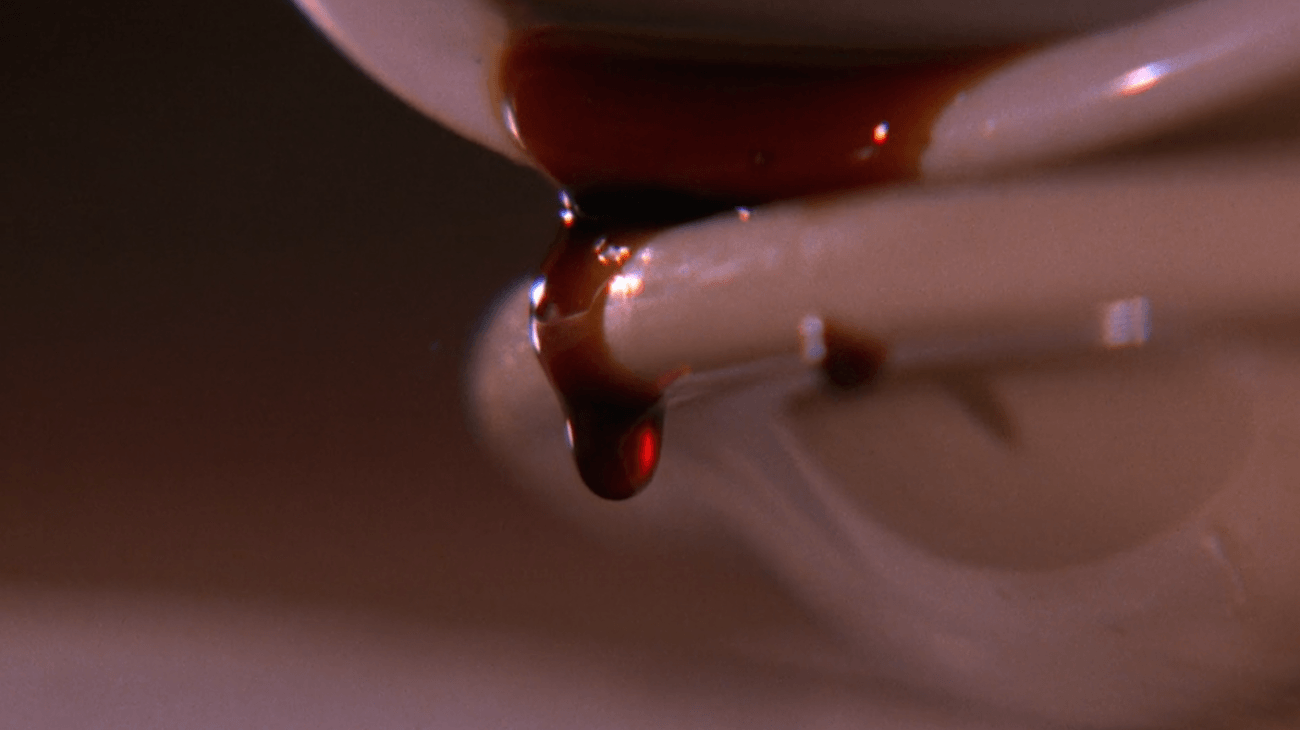

Other than that, this is a great exercise in old-school Peaks: everything feels slightly corroded by a widespread, indefinable sense of danger. There's the enormous close-ups of dripping syrup, histrionic and corny to be certain, but God bless the show for just going there and not thinking twice about it (and for the reverb-heavy syrup drup sound effect); there is the great use of close-ups in the scene where the three women with poems from Windom Earle start to assemble their thoughts, the camera probing at them menacingly. And there are the episodes most showy, celebrated parts, including the town-wide epidemic of getting a really bad shake in the right hand, accompanied by a rattle, breathy musical sting, and what the hall that's about, I couldn't definitely say; the evil that has been hovering around town starting to actively make its presence felt, I guess. Whatever it is, it's a nifty motif that pays offer to tremendous effect in the final moments of the episode, as Bob (Frank Silva) makes his return in the form of a shaking hand in a pool of light. That last minute and a half of the episode is top-drawer Twin Peaks if ever I saw it: ominous shots of empty hallways with ghostly phones ringing, with the camera steadily pushing in to give us the feeling of something stalking around aimlessly; and then that wonderful final set of images, as the show finally embraces with both arms its final form, a terrifying campfire story about the paranormal hauntings to be found out in the lonely depths of the dark woods at night. It's possibly my favorite sequence of the whole series not directed by Lynch. This is the very good shit, and this is exactly the reason it's worth suffering through all that deadwood that started so many episodes ago. Twin Peaks didn't just get good again; Twin Peaks got fucking great.

Grade: A

Written by Harley Peyton & Robert Engels

Directed by Stephen Gyllenhaal

Airdate: 18 April, 1991

Now this is how you ramp up a damn television series. With only three episodes left of Twin Peaks, mk. 1 (though at the time this one was made, I believe there was still optimism about getting a third season), Episode 27 brings us back tantalizingly close to the heights of the first half of the second season. It takes major strides to kick-off the very last run of conflicts that will animate Episodes 28 and 29, and does so while paying full attention the ominous atmosphere that used to be the show's calling card, and had been almost completely abandoned for months by the time this episode aired. Stephen Gyllenhaal (the father of the better-known acting Gyllenhaals) had been padding around directing television for ten years by the time he got his only Twin Peaks gig, doing nothing particularly noteworthy before or since, but the man deserves credit: his David Lynch impression was very much on point. This is among the best-directed episodes in the show's run, and it's a damn pity that Gyllenhaal didn't come along sooner; it's tempting to assume he might have been able to save some of the less-dodgy scripts along the way, and maybe even get a second episode under his belt before the show folded.

I think the best testament to how very damn good Episode 27 is, is that it's able to take material that very specifically has failed to work in the past, and without obviously changing anything about it, causing it to somehow be amazing. Take, for instance, the dreary matter of Windom Earle (Kenneth Welsh). Ever since we got our first really good look at Earle in the flesh, in Episode 22, the character has suffered from being enormously overhyped: the cold-blooded, merciless genius, the pure evil foil to the pure goodness of Kyle MacLachlan's Dale Cooper, has fairly consistently come off as a sniggering adolescent playing goofball pranks in between dressing up in ridiculously stupid costumes. And obviously, that could be the stuff of classic villainy - I have basically just described Batman's beloved archenemy, the Joker, have I not? - the gulf between how characters talk about Earle and how he's presented, between the solemn mood with which Twin Peaks presents evil, and the hammy way Welsh plays the character, has consistently undercut him.

And then, just like that, we get some absolutely splendid Earle this time around - consistently so, I would be willing to say. The scene where he wanders up to attack Garland Briggs (Don S. Davis) while dressed as a pantomime horse, fits squarely into the "idiot clown" side of the character's villainy, and yet it's such an unnerving, creepy scene. A lot of that is due simply to setting: an exterior scene, in the woods, in full daylight, is such an incongruous context even for a show like Twin Peaks to stage an attack. The sheer banal simplicity of the moment gives it a delirious quality missing from most of Earle's previous moments. A similar feeling attaches itself to an earlier scene, in which Briggs, Cooper, and Harry (Michael Ontkean) watch old 16mm footage of Earle, converted to VHS, babbling about the ancient rituals of a lost race, used to access the Black Lodge and celebrate its evil. The very perfunctory crappiness of the footage gives Welsh's unusually subdued performance - he's channeling a square, professorial vibe underneath the mumbling - a jolt of unreality that suits it extremely well. And even the more straightforward Earle moments, when he's just cackling with evil, seem to work better, somehow; Welsh is maybe a bit more reined-in, and Leo (Eric Da Re), fumblingly re-acquiring the humanity he never had before becoming a vegetable, makes for a strong enough contrast that Earle's villainy has more context.

Also, the final Earle scene is introduced with a shot of Leo and Briggs writhing on the ground, as the camera swirls around like a drunk housefly. That'll help with the atmosphere of anything.

Basically, Gyllenhaal is just really damn good at instilling a grim aura into everything that needs it. And we have not had that aura for ages. Even the show's incontestably worst plotline right now, the whole thing where Catherine (Piper Laurie) is trying to crack upon the surely-not-a-trap box left by the dead Thomas Eckhardt, manages to work: when Andrew (Dan O'Herlihy), a character I reliably forget exists when he's not onscreen, comes along to help his sister, his snappish tone with her is unexpected enough to feel like some nasty malevolent force has just intruded into their scene. An even better example: the early scene of Donna (Lara Flynn Boyle) examining her birth certificate and family albums in attic suffers, as the whole "did Ben actually father Donna?" plotline does, from taking too long to cover the points that the whole audience certainly ought to be able to predict. But it's so good - the action is staged directly in front of a large fan circulating air and creating a dramatic, strobe-like effect. It is, of course, a direct lift from Lynch, hardly inspired originality; but it's a good lift from Lynch, and it makes this scene shockingly tense as well as ineffably sad, and frankly, if the only good to come out of this plotline was this scene, I'd consider it worth it.

Just about the only things that I simply cannot sign off on are yet another scene between the ditsy sexpot-turned-beauty pageant cheat Lana (Robyn Lively) and her besotted ancient beau, Dwayne Milford (John Boylan), and the whole thing where Audrey (Sherilyn Fenn) tearily begs John Justice Wheeler (Billy Zane) to deflower her. The former is at least salvaged by Boylan's line readings. The latter is beyond redemption (what the hell happened to Audrey? They were doing so good at setting her up to be a sharklike business genius, and then just slammed her head-first into this godawful, vaguely pedophilic love story), despite Fenn's best efforts. But it does at least lead into a truly wonderful scene between Audrey and Pete (Jack Nance), the first time these characters have been thrown together as I recall, in which he gently offers to take her fishing, in the most kindly, grandfatherly tones. It's a terrific moment for two of the show's best actors.

Other than that, this is a great exercise in old-school Peaks: everything feels slightly corroded by a widespread, indefinable sense of danger. There's the enormous close-ups of dripping syrup, histrionic and corny to be certain, but God bless the show for just going there and not thinking twice about it (and for the reverb-heavy syrup drup sound effect); there is the great use of close-ups in the scene where the three women with poems from Windom Earle start to assemble their thoughts, the camera probing at them menacingly. And there are the episodes most showy, celebrated parts, including the town-wide epidemic of getting a really bad shake in the right hand, accompanied by a rattle, breathy musical sting, and what the hall that's about, I couldn't definitely say; the evil that has been hovering around town starting to actively make its presence felt, I guess. Whatever it is, it's a nifty motif that pays offer to tremendous effect in the final moments of the episode, as Bob (Frank Silva) makes his return in the form of a shaking hand in a pool of light. That last minute and a half of the episode is top-drawer Twin Peaks if ever I saw it: ominous shots of empty hallways with ghostly phones ringing, with the camera steadily pushing in to give us the feeling of something stalking around aimlessly; and then that wonderful final set of images, as the show finally embraces with both arms its final form, a terrifying campfire story about the paranormal hauntings to be found out in the lonely depths of the dark woods at night. It's possibly my favorite sequence of the whole series not directed by Lynch. This is the very good shit, and this is exactly the reason it's worth suffering through all that deadwood that started so many episodes ago. Twin Peaks didn't just get good again; Twin Peaks got fucking great.

Grade: A

Categories: television, twin peaks