To live and die in L.V.

A second review requested by Chris W, with thanks for contributing twice to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser.

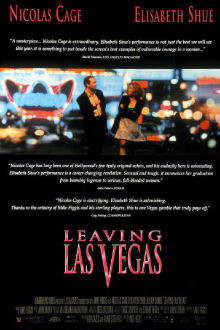

Back when it was brand new (and before I ever saw it), I read somebody, I cannot recall who, describe the plot of the 1995 film Leaving Las Vegas as follows: "A man tries to drink himself to death, and succeeds". That really does tell us whole thing about the film... not the "problem", because you can hardly call it a problem when a piece of art does precisely the thing that its creator intended for it to do. And in this case, what writer-director Mike Figgis (adapting the semi-autobiographical book by John O'Brien) intended was to provide us all with a scorched-earth presentation of alcoholism and prostitution in America at the end of the 1990s, heavy on the suffering.

I wouldn't go off and say this is necessarily a good thing or a bad thing, but it does mean that Leaving Las Vegas is one of the more extraordinarily unpleasant movies of its era, and I'm not entirely certain that there's a payoff to it. It definitely hits emotionally. And I won't even say that it hits emotionally by virtue of being manipulative: if anything the film is counter-manipulative, thanks to its oddly jaunty jazz score (composed by Figgis, in a cost-saving move). The music is, in fact, the one part of the movie that 100% no-two-ways-about-it does not work. It leaves the movie feeling dated (and I don't know why; it's not like jazzy film scores were common in the '90s, yet it still feels like nobody would dared have tried to get away with it at any other point in film history), and it cuts against the grain of the plot and the individual scenes in a manner that I simply refuse to believe could have been meant ironically. Figgis is not an irony-allergic director, but Leaving Las Vegas is quite perfectly straightforward in every other way. Still, you've got that music bopping and humming and promising that all of this is slightly cool and very upbeat and urbane, and you're trying to square that with the starving, miserable look in Nicholas Cage's eyes, and it just does not work. I mean, even if it felt like it was trying to evoke something "Las Vegas", but it's the wrong kind of jazz for that, and the film is happier depicting Vegas as a desperate, seedy hellhole than a home of glitz and flash and prefab glamour, anyway.

So anyway, the music blows. But back to my point, the music's not manipulative, and neither is anything else in this carefully shaggy movie. So anyway, on to the plot, since there's a bit more to it than just "drunk drinks himself into oblivion". The drunk in question is Ben Sanderson (Cage), a Hollywood screenwriter whose alcoholism has cost him everything in his personal life, and as the movie starts, is finally about to cost him his professional life, as well. The film's rather long pre-credits sequence (16 minutes!) watches Ben swirling around the drain, making a repugnant ass of himself with a woman, embarrassing his friends, and plowing through life with a mad jollity that's terrifying now, if it was ever anything else. Then he gets fired, and drops through the drain, and we spend the rest of the 112 minute film (the theatrical cut was one minute shorter, having shaved off some of the more sexually explicit shots and lines of dialogue) witnessing him flushed through the pipes.

Ben goes to Las Vegas, which the film does not go overboard in portraying as a Metaphor for American Excess, or anything like that (as in fellow 1995 release Showgirls), but just as a place where it's easy to overlooked in the act of sinning. Also because in Vegas, prostitution is legal, and that leads to our second broken soul, Sera (Elizabeth Shue), a hooker with a heart of silver, at least. She and Ben have what passes for a meet-cute in this universe (he almost runs her over and she yells at him), and on his second night in Vegas, Ben offers her $500 for a sexless conversation. Having recently been cut loose by her pimp Yuri (Julian Sands), Sera agrees, and for the next few days, the two basically fall in love. Only one rule governs their relationship: both of them pledge not to get in the way of the other's self-destructive path.

Leaving Las Vegas had the excellent fortune to come out just at the very start of the American indie film boom, when it was legitimately unlike anything that most of the people who encountered it had seen, at least recently (like so many heralded American masterworks of the 1990s-2010s, I don't think the film would have stood out so much in the fecund 1970s). The English-born Figgis's countrymen Ken Loach and Mike Leigh weren't yet at peak prominence on the western shores of the Atlantic (Loach's big return to form Carla's Song and Leigh's breakthrough Secrets & Lies were still a year off), and American independent filmmakers were then at their most passionately infatuated with the postmodern gamesmanship of Quentin Tarantino. The harsh kitchen-sink realism of Leaving Las Vegas was perfectly poised to make a huge impression, and it did precisely that, winning bottomless acclaim for the bluntness of its aesthetic, its refusal to look away from the degradation afflicting its characters, be it the beastly sex Sera endures (culminating in an unseen gang rape), or the out-of-control addiction that the make-up artists delight in splashing across Cage's face. Two decades later, I'm not sure that the film quite knows how far is too far: at times, it feels like it's wallowing in misery for misery's sake, particularly in its fascination with Sera's various sexual humiliations (and here that solitary minute between the theatrical and uncut versions is everything).

Still, even if I'm less impressed than I was when I first saw the movie two decades ago (and even then I found the "best of the year!" encomiums overblown), it's clearly the case that what works about Leaving Las Vegas works extremely well. It's also clearly the case that what works, first and foremost, are the two lead performances. 22 years later, neither Shue nor Cage has grown an ounce less impressive, though for opposite reasons. In Shue's case, we'd never seen anything like this from her, and we still haven't: while I'm not about to go around saying that she's not a solid, accomplished actress (hell, I'd even go to bat for her turn in Piranha 3D as one of the best lead performances in a 2010s creature feature, a rarer thing to get right than it might seem), she's never been prone to the kind of exhumation that happens in this film. Given by far the more thankless of the two roles, Shue not only treats a hoary cliché with enough dignity and sincerity to make it feel like the first time we've ever seen it, she also insists upon an arc of growth and change that's more implied by the screenplay than actually given.

In Cage's case, it's precisely that we've seen him give this kind of work, and it's astonishing to see what happens when it's given this one-of-a-kind framework. The actor, as I expect most everyone knows, is a bit of a manic hambone, given to elaborately overdone, aggressively tic-filled performances (except in those horrible cases where he just shuts down completely. All this time later, I'm still sore about how boring he was in Left Behind). And the thing is, his performance in Leaving Las Vegas - the film, I would remind you, for which he one his Oscar - is that. The random, demented giggling, the increasingly creepy refusal to blink, the florid stresses on almost the right word: this is the same exact Cage of the accidental camp classic The Wicker Man and the deliberate camp classic The Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call: New Orleans, with the same overclocked edge that makes it unclear whether it's the character or the actor having the psychotic break. The important difference being that it's in the context of a hyper-realist drama about the crushing weight of alcoholism, so that what plays as robust comedy in Bad Lieutenant (a film very much in dialogue with this one, perhaps by accident) plays as a horrifying lack of control, the death throes of a human being who can no longer even slightly pretend that he is or wants to be part of society. It would take only the slightest shifts in emphasis for this exact same performance to be goofy as shit; instead, it's far and away the most harrowing, emotionally powerful thing in Cage's career.

So marvelously does Cage's performance cut against the aesthetic that I'm just about willing to give Leaving Las Vegas a pass that it doesn't fully earn. The film was made on the fly and on the cheap, and it feels that way, for good and bad. Like a lot of cinematic realism, Leaving Las Vegas borrows the techniques of documentary filmmaking: jostling camera moves, ad hoc compositions. It's not my favorite aesthetic by any means, but even so, I don't think we can credit Figgis, cinematographer Declan Quinn, and editor John Smith with making the most of what they have available to them. It's a film dominated by close-ups and medium shots, in keeping with its mission of being a heavily character-driven thing, but after a while it no longer feels like the filmmakers want the camera to be anything other than a recording device. The realism here, then, is of a largely generic, passive sort, which is exactly why the performances erupt so powerfully out of the movie.

Even with its somewhat anonymous style, the film is a hell of a powerful thing: a little indiscriminate in its pursuit of human drudgery, undoubtedly, but its portrayal of addiction remains one of the most unsparing I've seen (the portrayal of prostitution could have done with one more draft). If it's one of the more prominent beneficiaries from the 1990s of the lazy critical shortcut that "sad=art", that takes away nothing from its great success as a character study; it's no masterpiece, pace Roger Ebert, but Shue and Cage are enough to make it a sterling example of the fertility of '90s indie cinema.

Back when it was brand new (and before I ever saw it), I read somebody, I cannot recall who, describe the plot of the 1995 film Leaving Las Vegas as follows: "A man tries to drink himself to death, and succeeds". That really does tell us whole thing about the film... not the "problem", because you can hardly call it a problem when a piece of art does precisely the thing that its creator intended for it to do. And in this case, what writer-director Mike Figgis (adapting the semi-autobiographical book by John O'Brien) intended was to provide us all with a scorched-earth presentation of alcoholism and prostitution in America at the end of the 1990s, heavy on the suffering.

I wouldn't go off and say this is necessarily a good thing or a bad thing, but it does mean that Leaving Las Vegas is one of the more extraordinarily unpleasant movies of its era, and I'm not entirely certain that there's a payoff to it. It definitely hits emotionally. And I won't even say that it hits emotionally by virtue of being manipulative: if anything the film is counter-manipulative, thanks to its oddly jaunty jazz score (composed by Figgis, in a cost-saving move). The music is, in fact, the one part of the movie that 100% no-two-ways-about-it does not work. It leaves the movie feeling dated (and I don't know why; it's not like jazzy film scores were common in the '90s, yet it still feels like nobody would dared have tried to get away with it at any other point in film history), and it cuts against the grain of the plot and the individual scenes in a manner that I simply refuse to believe could have been meant ironically. Figgis is not an irony-allergic director, but Leaving Las Vegas is quite perfectly straightforward in every other way. Still, you've got that music bopping and humming and promising that all of this is slightly cool and very upbeat and urbane, and you're trying to square that with the starving, miserable look in Nicholas Cage's eyes, and it just does not work. I mean, even if it felt like it was trying to evoke something "Las Vegas", but it's the wrong kind of jazz for that, and the film is happier depicting Vegas as a desperate, seedy hellhole than a home of glitz and flash and prefab glamour, anyway.

So anyway, the music blows. But back to my point, the music's not manipulative, and neither is anything else in this carefully shaggy movie. So anyway, on to the plot, since there's a bit more to it than just "drunk drinks himself into oblivion". The drunk in question is Ben Sanderson (Cage), a Hollywood screenwriter whose alcoholism has cost him everything in his personal life, and as the movie starts, is finally about to cost him his professional life, as well. The film's rather long pre-credits sequence (16 minutes!) watches Ben swirling around the drain, making a repugnant ass of himself with a woman, embarrassing his friends, and plowing through life with a mad jollity that's terrifying now, if it was ever anything else. Then he gets fired, and drops through the drain, and we spend the rest of the 112 minute film (the theatrical cut was one minute shorter, having shaved off some of the more sexually explicit shots and lines of dialogue) witnessing him flushed through the pipes.

Ben goes to Las Vegas, which the film does not go overboard in portraying as a Metaphor for American Excess, or anything like that (as in fellow 1995 release Showgirls), but just as a place where it's easy to overlooked in the act of sinning. Also because in Vegas, prostitution is legal, and that leads to our second broken soul, Sera (Elizabeth Shue), a hooker with a heart of silver, at least. She and Ben have what passes for a meet-cute in this universe (he almost runs her over and she yells at him), and on his second night in Vegas, Ben offers her $500 for a sexless conversation. Having recently been cut loose by her pimp Yuri (Julian Sands), Sera agrees, and for the next few days, the two basically fall in love. Only one rule governs their relationship: both of them pledge not to get in the way of the other's self-destructive path.

Leaving Las Vegas had the excellent fortune to come out just at the very start of the American indie film boom, when it was legitimately unlike anything that most of the people who encountered it had seen, at least recently (like so many heralded American masterworks of the 1990s-2010s, I don't think the film would have stood out so much in the fecund 1970s). The English-born Figgis's countrymen Ken Loach and Mike Leigh weren't yet at peak prominence on the western shores of the Atlantic (Loach's big return to form Carla's Song and Leigh's breakthrough Secrets & Lies were still a year off), and American independent filmmakers were then at their most passionately infatuated with the postmodern gamesmanship of Quentin Tarantino. The harsh kitchen-sink realism of Leaving Las Vegas was perfectly poised to make a huge impression, and it did precisely that, winning bottomless acclaim for the bluntness of its aesthetic, its refusal to look away from the degradation afflicting its characters, be it the beastly sex Sera endures (culminating in an unseen gang rape), or the out-of-control addiction that the make-up artists delight in splashing across Cage's face. Two decades later, I'm not sure that the film quite knows how far is too far: at times, it feels like it's wallowing in misery for misery's sake, particularly in its fascination with Sera's various sexual humiliations (and here that solitary minute between the theatrical and uncut versions is everything).

Still, even if I'm less impressed than I was when I first saw the movie two decades ago (and even then I found the "best of the year!" encomiums overblown), it's clearly the case that what works about Leaving Las Vegas works extremely well. It's also clearly the case that what works, first and foremost, are the two lead performances. 22 years later, neither Shue nor Cage has grown an ounce less impressive, though for opposite reasons. In Shue's case, we'd never seen anything like this from her, and we still haven't: while I'm not about to go around saying that she's not a solid, accomplished actress (hell, I'd even go to bat for her turn in Piranha 3D as one of the best lead performances in a 2010s creature feature, a rarer thing to get right than it might seem), she's never been prone to the kind of exhumation that happens in this film. Given by far the more thankless of the two roles, Shue not only treats a hoary cliché with enough dignity and sincerity to make it feel like the first time we've ever seen it, she also insists upon an arc of growth and change that's more implied by the screenplay than actually given.

In Cage's case, it's precisely that we've seen him give this kind of work, and it's astonishing to see what happens when it's given this one-of-a-kind framework. The actor, as I expect most everyone knows, is a bit of a manic hambone, given to elaborately overdone, aggressively tic-filled performances (except in those horrible cases where he just shuts down completely. All this time later, I'm still sore about how boring he was in Left Behind). And the thing is, his performance in Leaving Las Vegas - the film, I would remind you, for which he one his Oscar - is that. The random, demented giggling, the increasingly creepy refusal to blink, the florid stresses on almost the right word: this is the same exact Cage of the accidental camp classic The Wicker Man and the deliberate camp classic The Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call: New Orleans, with the same overclocked edge that makes it unclear whether it's the character or the actor having the psychotic break. The important difference being that it's in the context of a hyper-realist drama about the crushing weight of alcoholism, so that what plays as robust comedy in Bad Lieutenant (a film very much in dialogue with this one, perhaps by accident) plays as a horrifying lack of control, the death throes of a human being who can no longer even slightly pretend that he is or wants to be part of society. It would take only the slightest shifts in emphasis for this exact same performance to be goofy as shit; instead, it's far and away the most harrowing, emotionally powerful thing in Cage's career.

So marvelously does Cage's performance cut against the aesthetic that I'm just about willing to give Leaving Las Vegas a pass that it doesn't fully earn. The film was made on the fly and on the cheap, and it feels that way, for good and bad. Like a lot of cinematic realism, Leaving Las Vegas borrows the techniques of documentary filmmaking: jostling camera moves, ad hoc compositions. It's not my favorite aesthetic by any means, but even so, I don't think we can credit Figgis, cinematographer Declan Quinn, and editor John Smith with making the most of what they have available to them. It's a film dominated by close-ups and medium shots, in keeping with its mission of being a heavily character-driven thing, but after a while it no longer feels like the filmmakers want the camera to be anything other than a recording device. The realism here, then, is of a largely generic, passive sort, which is exactly why the performances erupt so powerfully out of the movie.

Even with its somewhat anonymous style, the film is a hell of a powerful thing: a little indiscriminate in its pursuit of human drudgery, undoubtedly, but its portrayal of addiction remains one of the most unsparing I've seen (the portrayal of prostitution could have done with one more draft). If it's one of the more prominent beneficiaries from the 1990s of the lazy critical shortcut that "sad=art", that takes away nothing from its great success as a character study; it's no masterpiece, pace Roger Ebert, but Shue and Cage are enough to make it a sterling example of the fertility of '90s indie cinema.