Blockbuster History Presents Arthuriana Week: The Classic Hollywood Epic

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: director Guy Ritchie's King Arthur: Legend of the Sword reminds us of the wide range of approaches that filmmakers have taken towards staging the Matter of Britain across the decades. It gives me great pleasure to spend a full week delving into some of the many other flavors of King Arthur films that have preceded Ritchie's contemporary stab at the material.

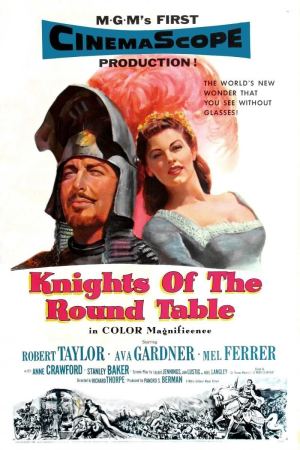

Of all the myths and legends of the English-speaking world, the legend of King Arthur and the Knights of Camelot has been among the most commonly adapted in the movies, second only to the exploits of socialist thief Robin Hood. So it's maybe a little surprising that it took until 1953 for the first relatively straight feature-length adaptation of the Arthur legendarium to be made in the United States (by which point, mind you, there'd already been three different adaptations of Mark Twain's A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court). The film in question is Knights of the Round Table, released in 1953 by MGM as that studio's very first CinemaScope production. And that is certainly the most interesting thing about it.

A little bit of history will be helpful, I think. The early 1950s were a period of great, swift change in the Hollywood landscape. Forced by the Supreme Court of the United States to start selling off their movie theaters in 1948 on the grounds that they film industry was a uniquely flagrant monopoly, and subsequently smacked in the face with the cold, dead fish of that new invention television, the American studios were all in a scramble to figure out how to stay alive in a suddenly very different commercial landscape. Widescreen was, famously, the solution that stuck around; widescreen, and a new embrace of elaborate costume epics on a scale that hadn't been seen since the decadent heyday of the silent films. Certain studios were better able to survive that process than others: 20th Century Fox, which premiered CinemaScope with The Robe, also in 1953, had a grand old time cranking out huge-scale epics for the next decade and a half, making a bit of a habit over the years out of nearly going bankrupt on a massive big-budget flop before hitting the jackpot with a massive big-budget blockbuster. Other studios transitioned to the new way of things with rather more growing pains, and MGM had maybe the roughest go of any of them. The studio that had been home to Arthur Freed's grandiose musical super-productions, and spent the '30s as the most opulent producer of the most outlandish eye candy proved surprisingly bad at moving into epic production; while MGM hung around long enough to give the world the monumental smash it Ben-Hur in 1959, the company had largely ceased to function as more than a desperately stapled-together distribution company by the start of the 1960s.

Knights of the Round Table was, anyway, one of the first MGM pictures trying to enter the strange new world of the second half the 20th Century, and it's not really very shocking, based on the results, that the effort would prove fatal. It's not that Knights of the Round Table is especially bad. Rather, it is spectacularly dull, handled with stiff direction by Richard Thorpe of actors who palpably wish not to be there, the three worst of them in the three roles that you'd particularly want to be populated by energized, likable performances. No question that the film looks expensive and immensely well-appointed, with location shooting in Ireland and Cornwall and every anamorphic widescreen frame stuffed to bursting with dozens of extras milling about busily. But it's also very much a film whose chief concern is making sure that you notice that it was expensive.

Officially adapted from Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur (the screenplay is by Talbot Jennings & Jan Lustig and Noel Langley), Knights of the Round Table sets a precedent to be followed by many a King Arthur film to follow it: it doesn't actually pay much attention to Malory. In this incarnation of the story, Arthur Pendragon (Mel Ferrer) is already an adult and one of several regional princelings on the island of Britain when he encounters the sword Excalibur, plunged into an anvil. More to the point, he's one of two leading candidates for the throne of all England, the other being Modred (Stanley Baker), the son of his half-sister Morgan Le Fay (Anne Crawford), and the sword has been a matter of legend ever since Arthur and Morgan's father Uther died. The only person who knows its location is Merlin (Felix Aylmer), some manner of career politician who has thrown his lot in as Arthur's closest councilor.

That Merlin, whatever the hell he is, surely isn't a wizard, points us in the direction that Knights of the Round Table plans to operate: this is, in its fumbling and idiotic way, a "realistic" version of the story, and in particular a realistic version obsessed to the point of folly with politics. The opening narration primly situates the action in the century of two of fallout from the Roman abandonment of Britain (the sets and costumes, meanwhile, promise that it's set sometime in 12th or 13th Century). The romantic triangle between Arthur, his queen Guinevere (Ava Gardner), and his finest knight, Lancelot (Robert Taylor) is the crisis on which the whole plot pivots, but only because it fits into the background scheming of Morgan and Modred, and it's this latter pair that actually drive virtually everything that happens. None of this, I would hasten to point out, is necessarily bad. But it's the same thing that kills off so many of the Bible epics that were coming into vogue around the same time: when the movie is staged to show off as much spectacle as can be roused, it really just sucks if that spectacle is swallowed up in endless scenes of people talking in the stiff, tight-assed way that '50s screenwriters all agreed connoted "olden times". For such a CinemaScope spectacle and all, it starts to get awfully conspicuous that the film elides all of its large-scale battles; the only combat we see is one-on-one dueling, and I will admit that at least those duels have the decency to be enjoyable to watch.

Anyway, the stilted, uptight vibe of the film is pretty much just standard operating procedure for movies of this type and this era, and not even all the stuffiness of a '50s epic can ruin the sweep of the landscape photography. As far as the production itself goes, the film is satisfyingly lush: there's nothing even remotely convincing in it on a historical level, but you'd have to be a pretty demanding, ungenerous viewer to pile on a '50s Hollywood film for not particularly caring about the difference between the 400s and the 1300s, or between the 1300s and the bright, clean cotton dyes of a 20th Century costume shop.

Where the film gets itself into rather more trouble is with its effects work. The marriage of actors in studios with location photography throughout is generally terrible; in particular, the scene at the sword in the stone is so crudely composited that it almost achieves a kind of fearsome beauty in its badness, like an accidental avant-garde film, ringing the characters in thick black lines like cartoons.

The worst thing about Knights of the Round Table, though, almost beyond question, are the leads. The supporting cast is mostly fine - Crawford is actively great, in fact, with her granite stare, and Aylmer is enjoyable if hardly revelatory. But there's just plain nothing going on between Taylor, Gardner, and Ferrer. For Taylor, that comes as no surprise: this was part of a mini-cycle of films he made under Thorpe's direction, all set in a chronologically indeterminate Merry Olde England, that the actor referred to as his "iron jockstrap" pictures. And once you've heard that most unforgettable phrase, it perfectly explains the pinched, pained expression that's the solitary thing Taylor ever wears on his face, in battle and lovemaking scenes alike. Ferrer, bless his heart, was simply not a good actor. Gardner, who shows off more charisma than this in literally every other one of her films that I've seen, is harder to figure out; possibly, she was feeding off of the exact energy that her co-stars were providing her, because she falls into the exact same mode of bland, declamatory joylessness that both Taylor and Ferrer use throughout.

The result is a mostly lifeless movie, and Thorpe's workaday staging (along with the general allergy to action) singularly fails to inject any life in around the edges. This is to the legend of King Arthur as those "child-safe" condensed versions of Malory are to the sexy, bloody, spiritually ecstatic original: buffed down to the point that it has no personality, trading exclusively on whatever pre-existing goodwill the audience has for the scenario and characters to generate interest in material that is itself quite anodyne. And even those children's versions of the story at least knew we were in it for the questing, the fighting, and the passion, not the political chess match!

Of all the myths and legends of the English-speaking world, the legend of King Arthur and the Knights of Camelot has been among the most commonly adapted in the movies, second only to the exploits of socialist thief Robin Hood. So it's maybe a little surprising that it took until 1953 for the first relatively straight feature-length adaptation of the Arthur legendarium to be made in the United States (by which point, mind you, there'd already been three different adaptations of Mark Twain's A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court). The film in question is Knights of the Round Table, released in 1953 by MGM as that studio's very first CinemaScope production. And that is certainly the most interesting thing about it.

A little bit of history will be helpful, I think. The early 1950s were a period of great, swift change in the Hollywood landscape. Forced by the Supreme Court of the United States to start selling off their movie theaters in 1948 on the grounds that they film industry was a uniquely flagrant monopoly, and subsequently smacked in the face with the cold, dead fish of that new invention television, the American studios were all in a scramble to figure out how to stay alive in a suddenly very different commercial landscape. Widescreen was, famously, the solution that stuck around; widescreen, and a new embrace of elaborate costume epics on a scale that hadn't been seen since the decadent heyday of the silent films. Certain studios were better able to survive that process than others: 20th Century Fox, which premiered CinemaScope with The Robe, also in 1953, had a grand old time cranking out huge-scale epics for the next decade and a half, making a bit of a habit over the years out of nearly going bankrupt on a massive big-budget flop before hitting the jackpot with a massive big-budget blockbuster. Other studios transitioned to the new way of things with rather more growing pains, and MGM had maybe the roughest go of any of them. The studio that had been home to Arthur Freed's grandiose musical super-productions, and spent the '30s as the most opulent producer of the most outlandish eye candy proved surprisingly bad at moving into epic production; while MGM hung around long enough to give the world the monumental smash it Ben-Hur in 1959, the company had largely ceased to function as more than a desperately stapled-together distribution company by the start of the 1960s.

Knights of the Round Table was, anyway, one of the first MGM pictures trying to enter the strange new world of the second half the 20th Century, and it's not really very shocking, based on the results, that the effort would prove fatal. It's not that Knights of the Round Table is especially bad. Rather, it is spectacularly dull, handled with stiff direction by Richard Thorpe of actors who palpably wish not to be there, the three worst of them in the three roles that you'd particularly want to be populated by energized, likable performances. No question that the film looks expensive and immensely well-appointed, with location shooting in Ireland and Cornwall and every anamorphic widescreen frame stuffed to bursting with dozens of extras milling about busily. But it's also very much a film whose chief concern is making sure that you notice that it was expensive.

Officially adapted from Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur (the screenplay is by Talbot Jennings & Jan Lustig and Noel Langley), Knights of the Round Table sets a precedent to be followed by many a King Arthur film to follow it: it doesn't actually pay much attention to Malory. In this incarnation of the story, Arthur Pendragon (Mel Ferrer) is already an adult and one of several regional princelings on the island of Britain when he encounters the sword Excalibur, plunged into an anvil. More to the point, he's one of two leading candidates for the throne of all England, the other being Modred (Stanley Baker), the son of his half-sister Morgan Le Fay (Anne Crawford), and the sword has been a matter of legend ever since Arthur and Morgan's father Uther died. The only person who knows its location is Merlin (Felix Aylmer), some manner of career politician who has thrown his lot in as Arthur's closest councilor.

That Merlin, whatever the hell he is, surely isn't a wizard, points us in the direction that Knights of the Round Table plans to operate: this is, in its fumbling and idiotic way, a "realistic" version of the story, and in particular a realistic version obsessed to the point of folly with politics. The opening narration primly situates the action in the century of two of fallout from the Roman abandonment of Britain (the sets and costumes, meanwhile, promise that it's set sometime in 12th or 13th Century). The romantic triangle between Arthur, his queen Guinevere (Ava Gardner), and his finest knight, Lancelot (Robert Taylor) is the crisis on which the whole plot pivots, but only because it fits into the background scheming of Morgan and Modred, and it's this latter pair that actually drive virtually everything that happens. None of this, I would hasten to point out, is necessarily bad. But it's the same thing that kills off so many of the Bible epics that were coming into vogue around the same time: when the movie is staged to show off as much spectacle as can be roused, it really just sucks if that spectacle is swallowed up in endless scenes of people talking in the stiff, tight-assed way that '50s screenwriters all agreed connoted "olden times". For such a CinemaScope spectacle and all, it starts to get awfully conspicuous that the film elides all of its large-scale battles; the only combat we see is one-on-one dueling, and I will admit that at least those duels have the decency to be enjoyable to watch.

Anyway, the stilted, uptight vibe of the film is pretty much just standard operating procedure for movies of this type and this era, and not even all the stuffiness of a '50s epic can ruin the sweep of the landscape photography. As far as the production itself goes, the film is satisfyingly lush: there's nothing even remotely convincing in it on a historical level, but you'd have to be a pretty demanding, ungenerous viewer to pile on a '50s Hollywood film for not particularly caring about the difference between the 400s and the 1300s, or between the 1300s and the bright, clean cotton dyes of a 20th Century costume shop.

Where the film gets itself into rather more trouble is with its effects work. The marriage of actors in studios with location photography throughout is generally terrible; in particular, the scene at the sword in the stone is so crudely composited that it almost achieves a kind of fearsome beauty in its badness, like an accidental avant-garde film, ringing the characters in thick black lines like cartoons.

The worst thing about Knights of the Round Table, though, almost beyond question, are the leads. The supporting cast is mostly fine - Crawford is actively great, in fact, with her granite stare, and Aylmer is enjoyable if hardly revelatory. But there's just plain nothing going on between Taylor, Gardner, and Ferrer. For Taylor, that comes as no surprise: this was part of a mini-cycle of films he made under Thorpe's direction, all set in a chronologically indeterminate Merry Olde England, that the actor referred to as his "iron jockstrap" pictures. And once you've heard that most unforgettable phrase, it perfectly explains the pinched, pained expression that's the solitary thing Taylor ever wears on his face, in battle and lovemaking scenes alike. Ferrer, bless his heart, was simply not a good actor. Gardner, who shows off more charisma than this in literally every other one of her films that I've seen, is harder to figure out; possibly, she was feeding off of the exact energy that her co-stars were providing her, because she falls into the exact same mode of bland, declamatory joylessness that both Taylor and Ferrer use throughout.

The result is a mostly lifeless movie, and Thorpe's workaday staging (along with the general allergy to action) singularly fails to inject any life in around the edges. This is to the legend of King Arthur as those "child-safe" condensed versions of Malory are to the sexy, bloody, spiritually ecstatic original: buffed down to the point that it has no personality, trading exclusively on whatever pre-existing goodwill the audience has for the scenario and characters to generate interest in material that is itself quite anodyne. And even those children's versions of the story at least knew we were in it for the questing, the fighting, and the passion, not the political chess match!