A review in brief

It would be disingenuous to call the film adaptation of A Chorus Line the worst possible version of the extraordinarily iconic stage musical. I mean, there's probably some director out there just waiting and waiting for the copyright to expire so they can stage a version about cannibal lizard-men on the moon. But it's really, really hard to think of how any Chorus Line can more perfectly manage the fun trick of being so rigid in its literalism that it chokes the air out of the movie by the end of its first number, while also missing the point of pretty much everything that makes the show the show. The result isn't as ghastly as some of the truly awful stage-to-screen hatchet jobs in history - paging Paint Your Wagon! - but it's arguably even worse for a film to be this airlessly boring.

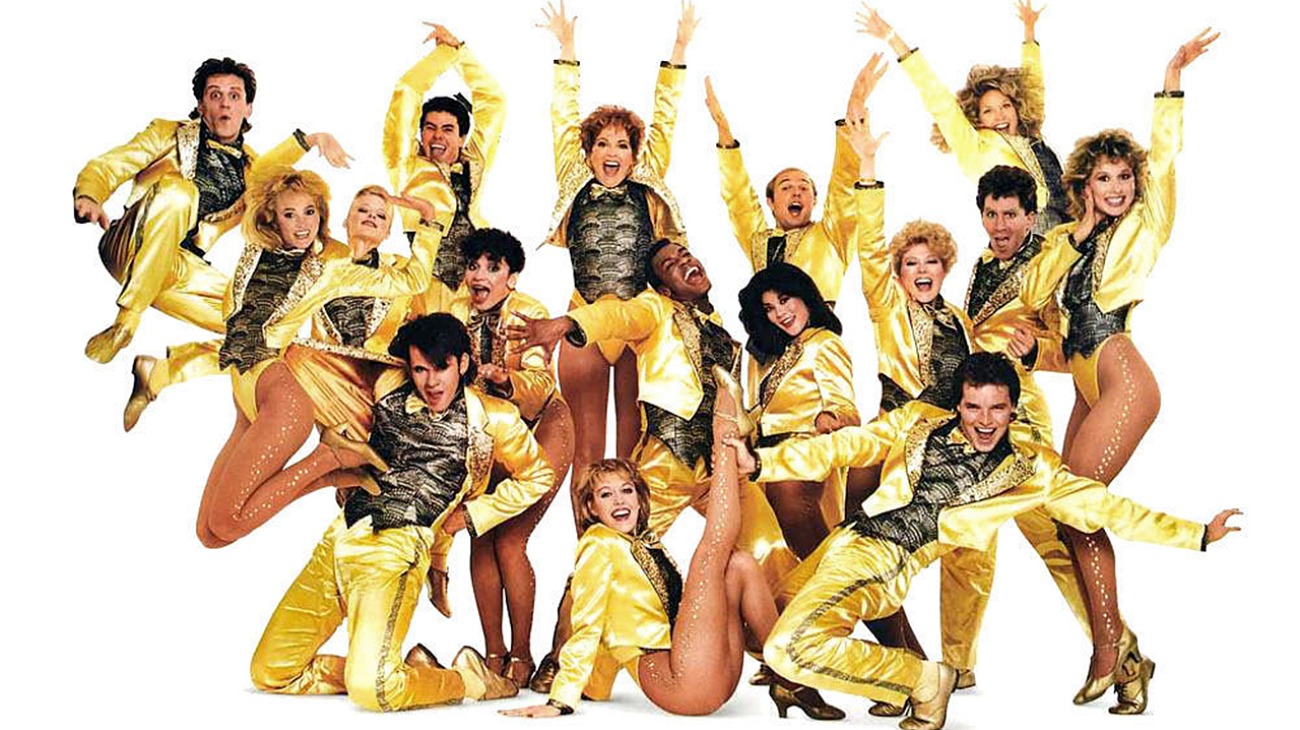

The plot: Zach (Michael Douglas) is directing hisself a new musical, and he needs to cast a chorus line. After the breathy opening "I Hope I Get It" (weirdly mixed together as a combination of inner monologue and spoken words), he's left with 17 dancers from whom to make his final selection, and he puts them through the painful process of baring their guts before him and the world. While this happens, he angrily fences verbally with his ex-lover Cassie (Alyson Reed), among the oldest of the competitors, and the only one whose career would seemingly put her above the grueling anonymity of a chorus line.

Casting Douglas pretty much killed the film right there - central to the idea of the material is that there is no real star, and putting the only real star in the cast in the role of the director automatically shifts the film's attention over to his slice of the plot, and director Richard Attenborough - a titanically ill-suited choice of filmmaker for this material - does not resist that impulse in the slightest. But reworking A Chorus Line as A Peevish Director & His Self-Reliant Ex isn't the only, or even the biggest problem. Worse by far is the lead-footed visual treatment of the musical numbers, in a film where the musical numbers matter so much that it references dancing in the title. Ronnie Taylor's camera dutifully clomps and sucks the wind out of the choreography (original choreographer Michael Bennett wanted nothing to do with the film, leaving Jeffrey Hornaday to reimagine things), and the lighting dismally plays at aesthetic realism in the most banal way, rubbing grit over everything without any sense of hardscrabble soulfulness. If you just absolutely need a film version of this material, the 2008 documentary Every Little Step will serve you better in every possible way.

The plot: Zach (Michael Douglas) is directing hisself a new musical, and he needs to cast a chorus line. After the breathy opening "I Hope I Get It" (weirdly mixed together as a combination of inner monologue and spoken words), he's left with 17 dancers from whom to make his final selection, and he puts them through the painful process of baring their guts before him and the world. While this happens, he angrily fences verbally with his ex-lover Cassie (Alyson Reed), among the oldest of the competitors, and the only one whose career would seemingly put her above the grueling anonymity of a chorus line.

Casting Douglas pretty much killed the film right there - central to the idea of the material is that there is no real star, and putting the only real star in the cast in the role of the director automatically shifts the film's attention over to his slice of the plot, and director Richard Attenborough - a titanically ill-suited choice of filmmaker for this material - does not resist that impulse in the slightest. But reworking A Chorus Line as A Peevish Director & His Self-Reliant Ex isn't the only, or even the biggest problem. Worse by far is the lead-footed visual treatment of the musical numbers, in a film where the musical numbers matter so much that it references dancing in the title. Ronnie Taylor's camera dutifully clomps and sucks the wind out of the choreography (original choreographer Michael Bennett wanted nothing to do with the film, leaving Jeffrey Hornaday to reimagine things), and the lighting dismally plays at aesthetic realism in the most banal way, rubbing grit over everything without any sense of hardscrabble soulfulness. If you just absolutely need a film version of this material, the 2008 documentary Every Little Step will serve you better in every possible way.

Categories: musicals, needless adaptations