Africa whispers

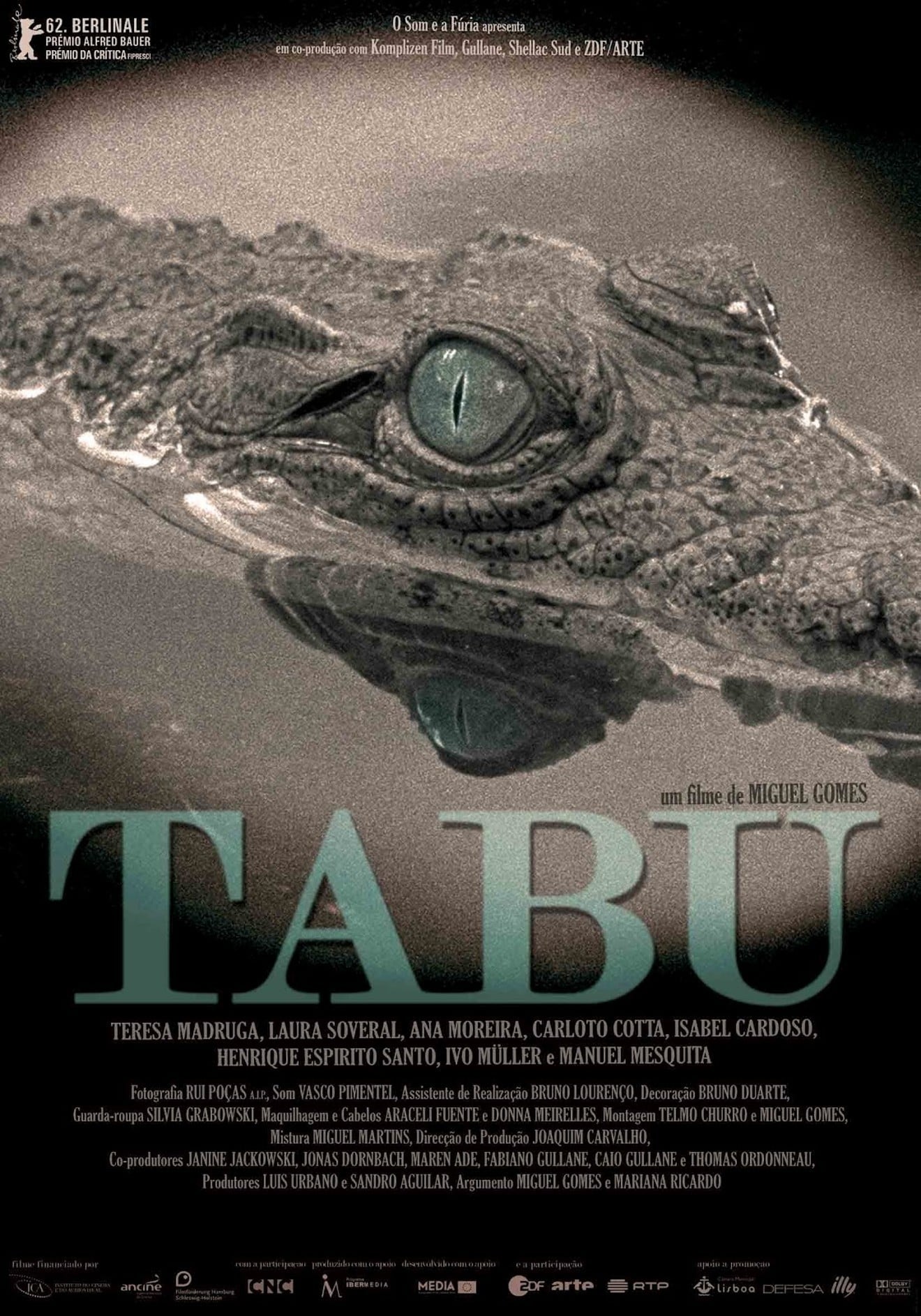

Thank the movie gods for Miguel Gomes and his Berlinale prize-winner Tabu for coming along at the eleventh hour to save the 2012 film year. The best prestige release season in years was fine and all, but one does start to get to putting together the ol' Top 10 list and relalise with disappointment how many of those almost-but-not-quite perfect scores went out to movies that are undoubtedly well-made, but not much else. After a point, you start to forget what actual boundary-pushing cinema looks like. Well, it looks like this.

The film borrows its title, structure, and the setting of European colonialism in the undeveloped world from F.W. Murnau's final film, Tabu: A Story of the South Seas from 1931, but it transmutes them enough that even suggesting that it's a remake is to completely miss the point of what Gomes and co-writer Mariana Ricardo are on about. The echoes are necessary and intentional, but that's all they are: echoes. In fact, Tabu echoes with a lot of things: Guy Maddin's experiments with silent film language are an exceedingly obvious touchstone, as is the Oscar-winning middlebrow epic Out of Africa, of all things. And that's just in the second half of the movie: the first half, without quoting anything in particular, manages to evoke and then mock the entire spirit of '60s European art cinema.

Tabu is a movie in two parts, plus a cryptic prologue that at first seems to be an exercise in top-notch ephemeral mood creation, then seems like an affection parody of art cinema, then ends up being revealed as both of those things and also a singularly resonant piece of foreshadowing. The movie proper, then begins, with a first part titled "Paradise Lost", which ends up providing about half of the running time, and takes place in nearly contemporary Lisbon, in the week surrounding New Year's Day, 2011 - the film further divides itself into sequences by announcing each new day with an implacable authoritative title card - as a middle-aged woman named Pilar (Teresa Madruga) frets and mopes about being lonely, frequently spending time with the other occupants of her apartment building, the very superstitious and very Catholic old woman Aurora (Laura Soveral) and Aurora's Cape Verdean housekeeper, Santa (Isabel Cardoso), when she's not letting herself be inexplicably depressed that a young Polish nun at the last moment that she wasn't going to stay with Pilar on a trip to Portugal. Long story short, Pilar desperately needs to keep herself surrounded by people, and Aurora and Santa are pretty much it.

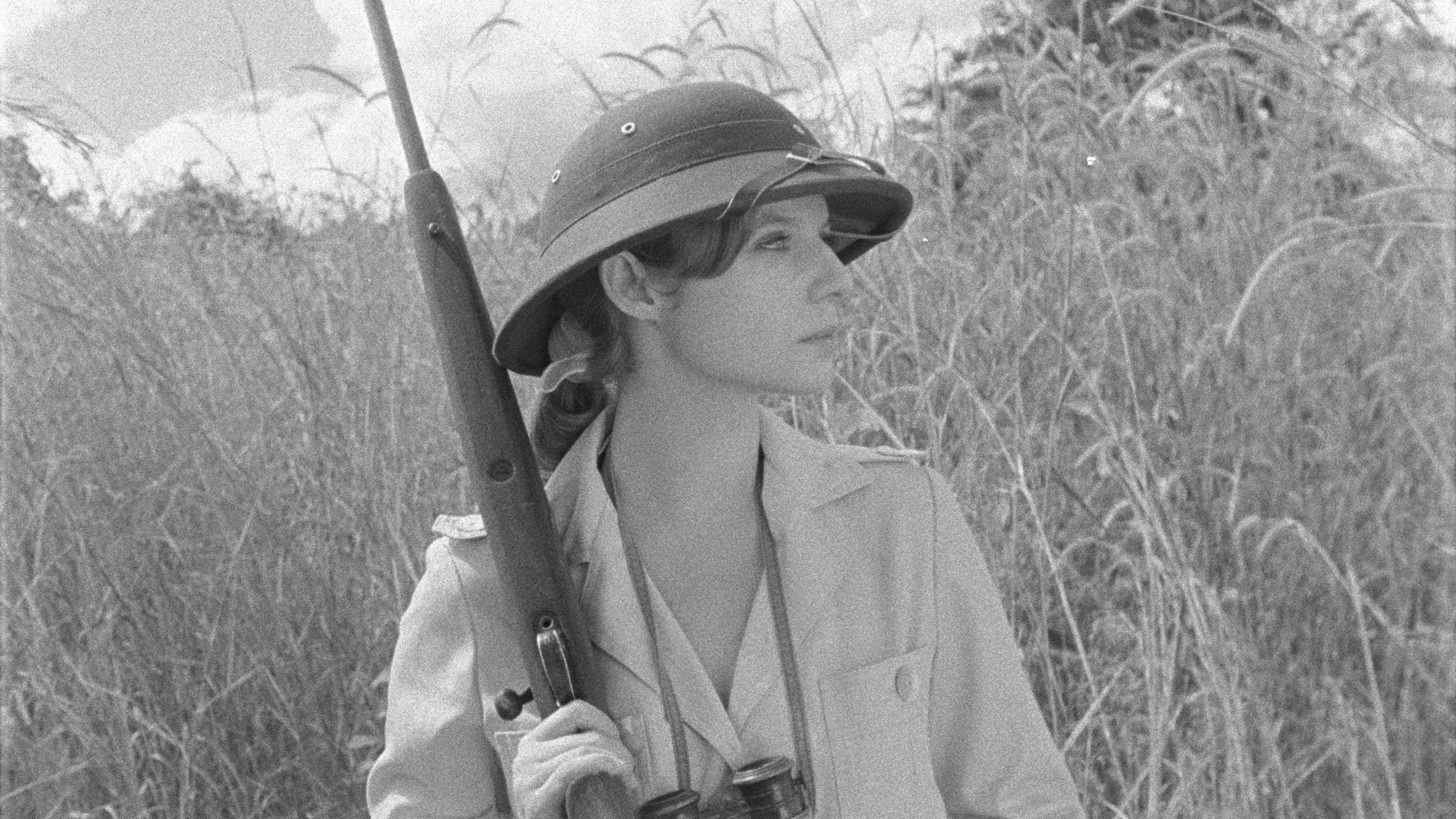

Without giving anything away - the film is grossly overstuffed with little surprises - a figure from Aurora's past shows up, and regales her two friends with a story from the old woman's past, when she was the wife of a plantation owner (Ivo Müller) in Africa - we can back our way into calculating that it's Mozambique in 1976, but that doesn't matter much - and played by Ana Moreira. Here, she fell in love with a recent transplant from Portugal (Carlotto Cotta), and their illicit affair played against the rising tensions of an anti-colonial independence movement.

This is largely a film about the memory of emotions, being gripped by the desire to be in another place in one's life - Pilar using the cinema, or protest movements, or young fake nuns as a way to pretend that she has another identity, Aurora losing the ability to distinguish between 21st Century Lisbon and 1970s Mozambique - and to depict that, Gomes relies on some of the most aggressive aesthetic choices of recent memory. For starters, Tabu is a black-and-white movie shot in the 1.37:1 aspect ratio of old cinema; for another, the "Paradise" segment is shot on grainy, diffuse 16mm film, and is almost completely silent: we hear Henrique Espírito Santo narrating the story, and we hear very muted sound effects of water and animals, but there is not a scrap of dialogue, or any vocalisation besides a group of natives singing wordlessly - the most cunning gesture of a film that hides its anti-colonialist musings under enough oblique layers that you could readily miss them altogether - despite the fact that we can see people speaking; there's just no sounds coming out.

It's one hell of an aggressive approach for a movie whose narrative line and attendant emotions are so simple and moving: no experimental film is this, but a very sweet-natured attempt to dramatise the out-of-control feeling of love (the film's single sex scene is a beautiful thing, erotic without being prurient or joyless, and comforting rather than lusty), and to depict through its very form the way that memory works - what says "memory" in film more than resembling the appearance of an old movie, but made with new cameras and lights to make it rich and sharp? Part of the reason that there is not speech in the second half, I am certain, is to suggest that we remember impressions and images rather than scripts: the visual memory of a place is what lingers, and thus the soundtrack is made out of vague ambient noises rather than specific words which are lost to Aurora's past. And all of this focuses our attention solely on the image and thus on the feeling created by the image: wonderful feelings they are, too: even allowing for the way Gomes problematises the narrative by casting the two lovers as willfully ignorant of the decaying system of white imperialism they represent, it's the most evocative cinematic love story in years.

If I focus on the second half, because it is the more "Oh my God!" part of the movie - when it became clear how the film was going to function, and suddenly the wandering sense of the first half snapped all into focus, I literally started tearing up with joy at what a bold, unique movie I was looking at - that's not to say that the first half is in any way lacking. It's unbelievably beautiful, for one thing: cinematographer Rui Poças indulges in all the contrast, shading, texture and show-off lighting effects that crisp black-and white provides. It's also droll, much more than anything I've said so far - in fact, the whole movie has an awfully flippant sense of dry humor, but nothing is more crazy and delightful than Aurora's meandering, pointless description of a loopy dream to explain why she lost money gambling, unless it is the scene between Pilar and a young Polish woman, in which they both try to communicate in English like a pair of malfunctioning robots.

Besides, the two halves are quite inseparable from each other: they share songs, lines of dialogue, symbolism, all of them bleeding into the two halves and unifying them into complete experience. This is what feelings feel like, Tabu communicates in its timeless images and unforced scenes of people dancing around the things they feel. It is a deep and challenging movie, it is a flowing and funny movie, and it is a masterpiece.

The film borrows its title, structure, and the setting of European colonialism in the undeveloped world from F.W. Murnau's final film, Tabu: A Story of the South Seas from 1931, but it transmutes them enough that even suggesting that it's a remake is to completely miss the point of what Gomes and co-writer Mariana Ricardo are on about. The echoes are necessary and intentional, but that's all they are: echoes. In fact, Tabu echoes with a lot of things: Guy Maddin's experiments with silent film language are an exceedingly obvious touchstone, as is the Oscar-winning middlebrow epic Out of Africa, of all things. And that's just in the second half of the movie: the first half, without quoting anything in particular, manages to evoke and then mock the entire spirit of '60s European art cinema.

Tabu is a movie in two parts, plus a cryptic prologue that at first seems to be an exercise in top-notch ephemeral mood creation, then seems like an affection parody of art cinema, then ends up being revealed as both of those things and also a singularly resonant piece of foreshadowing. The movie proper, then begins, with a first part titled "Paradise Lost", which ends up providing about half of the running time, and takes place in nearly contemporary Lisbon, in the week surrounding New Year's Day, 2011 - the film further divides itself into sequences by announcing each new day with an implacable authoritative title card - as a middle-aged woman named Pilar (Teresa Madruga) frets and mopes about being lonely, frequently spending time with the other occupants of her apartment building, the very superstitious and very Catholic old woman Aurora (Laura Soveral) and Aurora's Cape Verdean housekeeper, Santa (Isabel Cardoso), when she's not letting herself be inexplicably depressed that a young Polish nun at the last moment that she wasn't going to stay with Pilar on a trip to Portugal. Long story short, Pilar desperately needs to keep herself surrounded by people, and Aurora and Santa are pretty much it.

Without giving anything away - the film is grossly overstuffed with little surprises - a figure from Aurora's past shows up, and regales her two friends with a story from the old woman's past, when she was the wife of a plantation owner (Ivo Müller) in Africa - we can back our way into calculating that it's Mozambique in 1976, but that doesn't matter much - and played by Ana Moreira. Here, she fell in love with a recent transplant from Portugal (Carlotto Cotta), and their illicit affair played against the rising tensions of an anti-colonial independence movement.

This is largely a film about the memory of emotions, being gripped by the desire to be in another place in one's life - Pilar using the cinema, or protest movements, or young fake nuns as a way to pretend that she has another identity, Aurora losing the ability to distinguish between 21st Century Lisbon and 1970s Mozambique - and to depict that, Gomes relies on some of the most aggressive aesthetic choices of recent memory. For starters, Tabu is a black-and-white movie shot in the 1.37:1 aspect ratio of old cinema; for another, the "Paradise" segment is shot on grainy, diffuse 16mm film, and is almost completely silent: we hear Henrique Espírito Santo narrating the story, and we hear very muted sound effects of water and animals, but there is not a scrap of dialogue, or any vocalisation besides a group of natives singing wordlessly - the most cunning gesture of a film that hides its anti-colonialist musings under enough oblique layers that you could readily miss them altogether - despite the fact that we can see people speaking; there's just no sounds coming out.

It's one hell of an aggressive approach for a movie whose narrative line and attendant emotions are so simple and moving: no experimental film is this, but a very sweet-natured attempt to dramatise the out-of-control feeling of love (the film's single sex scene is a beautiful thing, erotic without being prurient or joyless, and comforting rather than lusty), and to depict through its very form the way that memory works - what says "memory" in film more than resembling the appearance of an old movie, but made with new cameras and lights to make it rich and sharp? Part of the reason that there is not speech in the second half, I am certain, is to suggest that we remember impressions and images rather than scripts: the visual memory of a place is what lingers, and thus the soundtrack is made out of vague ambient noises rather than specific words which are lost to Aurora's past. And all of this focuses our attention solely on the image and thus on the feeling created by the image: wonderful feelings they are, too: even allowing for the way Gomes problematises the narrative by casting the two lovers as willfully ignorant of the decaying system of white imperialism they represent, it's the most evocative cinematic love story in years.

If I focus on the second half, because it is the more "Oh my God!" part of the movie - when it became clear how the film was going to function, and suddenly the wandering sense of the first half snapped all into focus, I literally started tearing up with joy at what a bold, unique movie I was looking at - that's not to say that the first half is in any way lacking. It's unbelievably beautiful, for one thing: cinematographer Rui Poças indulges in all the contrast, shading, texture and show-off lighting effects that crisp black-and white provides. It's also droll, much more than anything I've said so far - in fact, the whole movie has an awfully flippant sense of dry humor, but nothing is more crazy and delightful than Aurora's meandering, pointless description of a loopy dream to explain why she lost money gambling, unless it is the scene between Pilar and a young Polish woman, in which they both try to communicate in English like a pair of malfunctioning robots.

Besides, the two halves are quite inseparable from each other: they share songs, lines of dialogue, symbolism, all of them bleeding into the two halves and unifying them into complete experience. This is what feelings feel like, Tabu communicates in its timeless images and unforced scenes of people dancing around the things they feel. It is a deep and challenging movie, it is a flowing and funny movie, and it is a masterpiece.