The misery of 1935

In all of movie history, Victor Hugo's 1862 goliath of a novel Les Misérables has been filmed more times than any other single work of literature by a writer not named Charles Dickens or William Shakespeare; shockingly, only twice was that filming done in Hollywood, where prestigious, dour literature goes to be tricked out with movie stars on the way to impressing critics at middleweight publications and receiving nominations for Oscars, but not actually winning (and yes, there are two predominately British film productions - one the notorious film version of the megalithic West End musical - that are Hollywood in all but name. But we are going with a strict definition here). How there can be only two American Les Misérableses, and ninety-eight jillion American Christmas Carols, I cannot quite say, but there you have it.

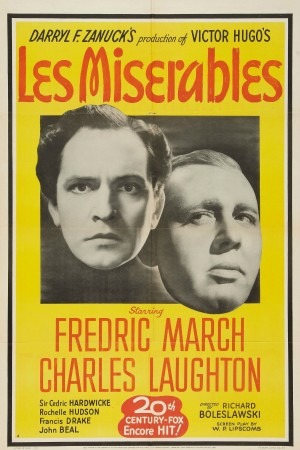

The first of these Hollywood Les Misérables adaptations, produced by 20th Century Pictures in 1935, the last year of its independent existence before teaming up with Fox Film Corporation, is also probably the best English-language movie made out of the story. Which is not by any means the same as calling it the best adaptation: in fact, in keeping with most of its successors, it becomes increasingly divorced from Hugo's original as it moves on and eventually just cuts the end off square, having concluded that it's better to make a sprawling moral and religious fable a straightforward, self-contained "obsessed cop vs. reformed ex-con" thriller and not worry about the hundred-odd pages of indispensable writing that follow the end of the book's most obvious, surface-level conflict. Incidentally, I can't find it in my heart to feel like spoiling a 150-year old book and cornerstone of Western literary history is out of bounds, so I'm going right to the end of the movie to say what I'm talking about: it ends with Javert's suicide, thereby freeing ex-con and parole-breaker Jean Valjean from his life hiding in the shadows, always terrified of being caught and sent back to die in prison. That is a fair place to end the book if you have an extraordinarily literal notion of what the book is about: and it's probably fair to assume that dramatising a man's dying in a state of spiritual grace is harder for cinema than dramatising a lifelong chase movie. But it also cheapens what Les Misérables is, a little bit, to do that.

I have already lost the thread. Let's back up: the '35 Les Misérables is not, all things considered, very good Hugo, 'tis true. But it's a pretty great 1935 prestige picture, one of the highlights of a year where tony literary adaptations were at their height; MGM's Mutiny on the Bounty and David Copperfield, and Warners' A Midsummer Night's Dream were all out the same year, and all four films in question managed to swing a Best Picture Oscar nomination, to boot (Bounty won), so it was clearly a project Hollywood was deeply excited about at the time.

What makes Les Misérables so very good is largely down to three men, none of whom are director Richard Boleslawski, though this is almost beyond debate the best film of his career (give or take Three Godfathers and maybe Theodora Goes Wild if you are an extremely generous Irene Dunne nut), and one where his habit of insisting on the gravity of his themes actually works to the film's benefit (and he sneaks in a couple of great scenes: the opening trial, in which Valjean is sentenced - an invention of the movie's - is marvelous). No, the men in question are, firstly, Gregg Toland, one of the legendary cinematographers of the '30s and '40s - his masterwork is of course the unimpeachable Citizen Kane - making here the earliest of all his movies that still has anything resembling contemporary currency (and netting the first of his six Oscar nominations), though he'd already shot tens of movies by this point. Certainly, the look of the film bespeaks a talented expert in his field, not trying to prove anything, but just showing off how fantastically he could manipulate lighting and focus. Need a dappled, storybook park? There you go. A nightmarish Paris beset by violence and mayhem? Does Expressionist exaggeration work, or do you want more like a contrasty war film? Because Gregg Toland can do it both ways. A windy, rainy night of confusion and despair that's half melodrama, half horror, and half realist drama? Sure thing, and Toland doesn't even mind if that adds up to three halves. His lensing of the sewers of Paris following the June Rebellion of 1832 are a particular masterpiece, showcasing the limitless depth of field that he and Orson Welles would do so much good with six years later, creating a foreboding world of deep, impenetrable black abysses, bringing that famous setpiece to life in the most awesome way possible.

The other two men are a pair of ringers, exactly the protagonist and antagonist you want if you're a producer of a mid-'30s prestige picture and you deeply want it to be moving and rich and not a tormented marathon of Paul Muni looking waxenly noble for two hours: as Jean Valjean, who stole a loaf of bread to feed his starving nieces and nephews, we have Fredric March, previously the finest Dr. Henry Jekyll in screen history (that being the 1931 incarnation), and as Inspector Javert, the merciless policeman hounding Valjean for twenty years, Charles Laughton, of the demonic baby face, perhaps the most consistently brilliant movie villain of the '30s, though he was certainly capable of more than just richly detailed, theatrical bad guys (the actors had previously been seen together just the year prior in The Barretts of Wimpole Street, certainly not one of the great '30s prestige pictures, but better, anyway, than you'd expect it to be). March is inspired casting, Laughton excitingly unconventional (other than his implacable presence, there's nothing at all about him that suggests the character as Hugo wrote him), and both of them serve to elevate the material up to the rafters, which is especially vital given how much of the material has been shorn away to focus on just these two men and their various encounters over two decades, leaving it, in places, as a heavily designed two-hander. With more screentime and the story's more extreme arc, March leaves the better impression - and his small performance as Valejan's look-alike, Champmathieu, is remarkably clear of any gimmicks that would seem inevitable - creating a significantly more angry, irascible Valjean than the one the book implies. Laughton's imperious bully is nothing the actor couldn't do blindfolded, though he still smuggles in any number of mild, delicate touches, and given the extreme focus screenwriter W.P Lipscomb's script lends to Javert's personal history and moral absolutism, it's those touches that really sell the character.

Performance-wise, those are almost the only reason to bother with the film: there's not much room in this version for other characters to land (Florence Eldridge's suffering mother and prostitute Fantine counts as just a cameo), and the young lovers who are the only other major characters, Valjean's adopted daughter Cosette (Rochelle Hudson) and student rebel leader Marius (John Beal) are completely unlikable - Hudson plays her character a Woolworth's knock-off of Miriam Hopkins - with Frances Drake's turn as Marius's secretary Eponine (told you the second half started drifting away from Hugo as it went on) offering only a caricatured version of spark and bite. Cedric Hardwicke's small role as the bishop who turns Valjean to a life of goodness is fine, if sort of like every other Hardwicke performance; but he's barely in the film.

Besides turning the story mostly into a feature-length chase, the most fascinating change the movie makes is to strip out Hugo's politics: Les Misérables being very pointedly a story about the wretched poor rising up to demand the basic rudiments of a decent life by force of arms, and that having particularly serious overtones during the Great Depression, the last time that actual Communism had any kind of popular support in the United States, it's no shock that the film makes a serious effort to show that no, actually, popular uprisings are bad. Marius, though he leads the student revolt, is eager to claim that there is no political angle to his protest; he just wants to agitate for prison reform. When the other students end up fighting for broad revolution than that, it's quickly depicted in hellish visuals as the very worst thing imaginable, particular with Enjolras, in a virtually non-existent appearance, portrayed by the great ham John Carradin (in his very first credited appearance!) lit from beneath to look literally Satanic.

Almost everything else changed from the book is solely in service of condensing the plot as much as possible, or explaining the backstory more fully (the first 25 minutes or so of the film are almost complete invention, dramatising Valjean and Javert's prehistory as master and prisoner on the galleys; galleys that are a laughable anachronism, by the way). And for the most part, this works: the first hour of the film is tight and mesmerising, giving the two leads all the chances they need to make this epic battle of law and order vs. justice and mercy seem more human than abstract. As it goes along, and the Marius/Cosette love affair starts to predominate, the story begins to feel cramped and rushed, though the last scene is so damn good that it tends to counterbalance much of the arbitrary screenwriting it took to get there.

It has its problems, no doubt, and there's a sheen of '30s classiness that leaves it slightly unable to breathe (for all Toland's mastery, the sets never look like anything but sets; this tends to be a problem with dramas of the era more than with the outwardly fantastical movies, comedies, and action films). But there's so much to love that none of the flaws seem trivial and easily-overlooked, and while there's no such thing as a timeless '30s Oscarbait literary adaptation, this comes pleasantly within spitting distance of that mark.

The first of these Hollywood Les Misérables adaptations, produced by 20th Century Pictures in 1935, the last year of its independent existence before teaming up with Fox Film Corporation, is also probably the best English-language movie made out of the story. Which is not by any means the same as calling it the best adaptation: in fact, in keeping with most of its successors, it becomes increasingly divorced from Hugo's original as it moves on and eventually just cuts the end off square, having concluded that it's better to make a sprawling moral and religious fable a straightforward, self-contained "obsessed cop vs. reformed ex-con" thriller and not worry about the hundred-odd pages of indispensable writing that follow the end of the book's most obvious, surface-level conflict. Incidentally, I can't find it in my heart to feel like spoiling a 150-year old book and cornerstone of Western literary history is out of bounds, so I'm going right to the end of the movie to say what I'm talking about: it ends with Javert's suicide, thereby freeing ex-con and parole-breaker Jean Valjean from his life hiding in the shadows, always terrified of being caught and sent back to die in prison. That is a fair place to end the book if you have an extraordinarily literal notion of what the book is about: and it's probably fair to assume that dramatising a man's dying in a state of spiritual grace is harder for cinema than dramatising a lifelong chase movie. But it also cheapens what Les Misérables is, a little bit, to do that.

I have already lost the thread. Let's back up: the '35 Les Misérables is not, all things considered, very good Hugo, 'tis true. But it's a pretty great 1935 prestige picture, one of the highlights of a year where tony literary adaptations were at their height; MGM's Mutiny on the Bounty and David Copperfield, and Warners' A Midsummer Night's Dream were all out the same year, and all four films in question managed to swing a Best Picture Oscar nomination, to boot (Bounty won), so it was clearly a project Hollywood was deeply excited about at the time.

What makes Les Misérables so very good is largely down to three men, none of whom are director Richard Boleslawski, though this is almost beyond debate the best film of his career (give or take Three Godfathers and maybe Theodora Goes Wild if you are an extremely generous Irene Dunne nut), and one where his habit of insisting on the gravity of his themes actually works to the film's benefit (and he sneaks in a couple of great scenes: the opening trial, in which Valjean is sentenced - an invention of the movie's - is marvelous). No, the men in question are, firstly, Gregg Toland, one of the legendary cinematographers of the '30s and '40s - his masterwork is of course the unimpeachable Citizen Kane - making here the earliest of all his movies that still has anything resembling contemporary currency (and netting the first of his six Oscar nominations), though he'd already shot tens of movies by this point. Certainly, the look of the film bespeaks a talented expert in his field, not trying to prove anything, but just showing off how fantastically he could manipulate lighting and focus. Need a dappled, storybook park? There you go. A nightmarish Paris beset by violence and mayhem? Does Expressionist exaggeration work, or do you want more like a contrasty war film? Because Gregg Toland can do it both ways. A windy, rainy night of confusion and despair that's half melodrama, half horror, and half realist drama? Sure thing, and Toland doesn't even mind if that adds up to three halves. His lensing of the sewers of Paris following the June Rebellion of 1832 are a particular masterpiece, showcasing the limitless depth of field that he and Orson Welles would do so much good with six years later, creating a foreboding world of deep, impenetrable black abysses, bringing that famous setpiece to life in the most awesome way possible.

The other two men are a pair of ringers, exactly the protagonist and antagonist you want if you're a producer of a mid-'30s prestige picture and you deeply want it to be moving and rich and not a tormented marathon of Paul Muni looking waxenly noble for two hours: as Jean Valjean, who stole a loaf of bread to feed his starving nieces and nephews, we have Fredric March, previously the finest Dr. Henry Jekyll in screen history (that being the 1931 incarnation), and as Inspector Javert, the merciless policeman hounding Valjean for twenty years, Charles Laughton, of the demonic baby face, perhaps the most consistently brilliant movie villain of the '30s, though he was certainly capable of more than just richly detailed, theatrical bad guys (the actors had previously been seen together just the year prior in The Barretts of Wimpole Street, certainly not one of the great '30s prestige pictures, but better, anyway, than you'd expect it to be). March is inspired casting, Laughton excitingly unconventional (other than his implacable presence, there's nothing at all about him that suggests the character as Hugo wrote him), and both of them serve to elevate the material up to the rafters, which is especially vital given how much of the material has been shorn away to focus on just these two men and their various encounters over two decades, leaving it, in places, as a heavily designed two-hander. With more screentime and the story's more extreme arc, March leaves the better impression - and his small performance as Valejan's look-alike, Champmathieu, is remarkably clear of any gimmicks that would seem inevitable - creating a significantly more angry, irascible Valjean than the one the book implies. Laughton's imperious bully is nothing the actor couldn't do blindfolded, though he still smuggles in any number of mild, delicate touches, and given the extreme focus screenwriter W.P Lipscomb's script lends to Javert's personal history and moral absolutism, it's those touches that really sell the character.

Performance-wise, those are almost the only reason to bother with the film: there's not much room in this version for other characters to land (Florence Eldridge's suffering mother and prostitute Fantine counts as just a cameo), and the young lovers who are the only other major characters, Valjean's adopted daughter Cosette (Rochelle Hudson) and student rebel leader Marius (John Beal) are completely unlikable - Hudson plays her character a Woolworth's knock-off of Miriam Hopkins - with Frances Drake's turn as Marius's secretary Eponine (told you the second half started drifting away from Hugo as it went on) offering only a caricatured version of spark and bite. Cedric Hardwicke's small role as the bishop who turns Valjean to a life of goodness is fine, if sort of like every other Hardwicke performance; but he's barely in the film.

Besides turning the story mostly into a feature-length chase, the most fascinating change the movie makes is to strip out Hugo's politics: Les Misérables being very pointedly a story about the wretched poor rising up to demand the basic rudiments of a decent life by force of arms, and that having particularly serious overtones during the Great Depression, the last time that actual Communism had any kind of popular support in the United States, it's no shock that the film makes a serious effort to show that no, actually, popular uprisings are bad. Marius, though he leads the student revolt, is eager to claim that there is no political angle to his protest; he just wants to agitate for prison reform. When the other students end up fighting for broad revolution than that, it's quickly depicted in hellish visuals as the very worst thing imaginable, particular with Enjolras, in a virtually non-existent appearance, portrayed by the great ham John Carradin (in his very first credited appearance!) lit from beneath to look literally Satanic.

Almost everything else changed from the book is solely in service of condensing the plot as much as possible, or explaining the backstory more fully (the first 25 minutes or so of the film are almost complete invention, dramatising Valjean and Javert's prehistory as master and prisoner on the galleys; galleys that are a laughable anachronism, by the way). And for the most part, this works: the first hour of the film is tight and mesmerising, giving the two leads all the chances they need to make this epic battle of law and order vs. justice and mercy seem more human than abstract. As it goes along, and the Marius/Cosette love affair starts to predominate, the story begins to feel cramped and rushed, though the last scene is so damn good that it tends to counterbalance much of the arbitrary screenwriting it took to get there.

It has its problems, no doubt, and there's a sheen of '30s classiness that leaves it slightly unable to breathe (for all Toland's mastery, the sets never look like anything but sets; this tends to be a problem with dramas of the era more than with the outwardly fantastical movies, comedies, and action films). But there's so much to love that none of the flaws seem trivial and easily-overlooked, and while there's no such thing as a timeless '30s Oscarbait literary adaptation, this comes pleasantly within spitting distance of that mark.