Try to find the sunny side of life

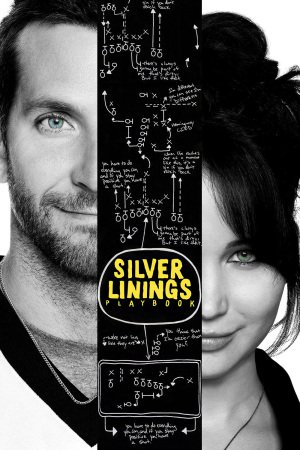

The critic must not try to hide his biases when they might get in the way of the review; and boy, did I ever head into Silver Linings Playbook, at long last, with a basketful of biases. "Bradley Cooper as a romantic lead" is very close to the least appealing combination of performer and role that I think I could dream up in contemporary English-language filmmmaking, and "mentally ill people are like you and I only more free-spirited and quirkier" vies only with "British sex comedy from the '60s cribbing blindly from the French New Wave playbook" for the title of genre that I've found to have the most consistently high miss-to-hit ratio. Plus, call it snobbishness if you want, but there's something about a comedy that manages to pick up that many Oscar nominations that puts me instantly on the defensive: there has to be something pretty unpleasantly high-minded going on for that kind of awards recognition. All of which is double-edged: I was primed to dislike the movie very much, but all it had to do to finagle a passing grade was not suck as hard as my expectations.

Lo and behold, Silver Linings Playbook does not suck, though it's a far cry from any idea of great storytelling - to say absolutely nothing at all about great cinema - that overlaps with my own to a significant degree. It's the most comfortingly mainstream film yet made by writer-director David O. Russell, a filmmaker whose entire career has been more or less one film after another of finding out exactly how much indie movie spunk he can inject into a largely formulaic scenario before he starts to banish it to the arthouse ghetto; there's less of it here than ever before, although the film certainly announces itself as a Sharp, Tart-Tongued Indie of the '90s tradition where Russell first made his name with Spanking the Monkey and Flirting with Disaster (the latter of which remains, I'd contend, his most overall successful film), what with its wall-to-wall cast of fast talking crazy people being sarcastic, and its signature scene in which the two leads banter over their history of psych medication.

Adapted - with much invention, I am given to understand - from a book by Matthew Quick, the movie positions itself, somewhat effectively, as a successor to the screwball romantic comedies of the 1930s, with bipolar rageagholic Pat Solitano (Cooper) getting sprung from a mental health facility, where he ended up after beating his wife's boyfriend almost to death, by his overweening mother Dolores (Jacki Weaver, whose Supporting Actress Oscar nomination is absolutely inscrutable to me know that I've seen the performance), and taken back to live with her and his unemployed father Pat Sr. (Robert De Niro), presently making ends meet as a bookie. Skip ahead a bit - a lot of a bit, in fact, for unlike the '30s screwballs, Silver Linings Playbook sees no reason to push the pace along at all, and thus do we end up with a 122-minute version of a story almost morally obligated to clock in around 90 - and Pat is repeatedly crossing paths with Tiffany Maxwell (Jennifer Lawrence), sister of his good friend's wife, and like him, dealing with profound emotional difficulties: her latent depression was sent into overdrive when her husband died, and her attempts to self-medicate through sex have left her something of a social pariah. Skip ahead a bit more, and they make a deal: she'll help him circumvent the restraining order his wife has against him by passing letters, if he'll be her partner at a dance competition. Of course, this prickly deal between them, with all the sharp edges of deliberate, willful unlikability both sides invest themselves with, blossoms into romantic attraction, and if you think that's a spoiler, then you don't know enough about movies to deserve to see this one.

It's certainly overstating things to call the script a disaster, though certainly, it's too obviously proud of how insouciant it's being, and has a vastly overrated sense of its own creativity (pro tips: giving a standard-issue Quirky Romantic Comedy a facelift with mental illness, and disguising your Manic Pixie Dream Girl by making her mean, are not creative) and insight into emotionally disordered people. There's some good in it: the family dynamics between the two Pats and the barely-present Dolores have a comfortably intimate level of detail: it's terrifically obvious that these are people who have known each other for years and years before we've seen them, and have a whole host of codes and behaviors that they're all keyed-in to (a particular delight: Dolores's default mode of making "crabby snacks and homemades" as the dining accompaniment to all activities). And if, in general, the characters suffer from the movie version of these mental ailments rather than the actual real-life one (Tiffany's alleged depression, which manifests itself solely when the drama requires it, is a particularly glaring example), at least we're never given any of the usual "sensitive soul who understands a deeper truth and just needs love" bromides in relationship to Pat; indeed, those very tropes are openly mocked in a film quite content to let its characters glower and shout at each other and generally behave like assholes. Loveable assholes, sure; you can't have everything.

Regardless, the script is very much the film's weakness, and everything that works has do so by fighting against it. Russell's direction, alas, does not fight very hard: he gives in to a wholly ineffective impulse to visualise Pat's sped-up mania by using a lot of swift, flowing camera movements, and a sort of ADHD approach to POV (there's a shot fairly early on where, inexplicably, the camera suddenly takes an immediate interest in a close-up of Pat's hands). The performances, across the board, are tetchy and one-note: Bradley Cooper IS manic! Robert De Niro IS short-tempered! Jacki Weaver IS suburban! But even to get to that point requires at least a bit of effort, and it's shocking to this inveterate Cooper-hater to see just how much he's actually able to elevate the material. Better still is Lawrence, saddled with a gruelingly under-written character, a blank slate of female traits written solely to be the sounding board for the real protagonist's journey, and while there has never been an actress alive who could make a truly brilliant character out of that role - even in as well-written a film as Bringing Up Baby, an actress as great as Katharine Hepburn couldn't quite pull it off - Lawrence manages to find something at all to cling to and wrestle up from the depths, suggesting at least that her functional cardboard character is a real flesh-and-blood human.

Cooper and Lawrence both being pretty movie stars actually helps the movie, too, for it changes the battleground on which it's fighting: it makes it a Movie Star Picture, to which we bring a relaxed need for rich psychological authenticity, looking instead for an appealing, entertaining simulacrum of the same. The paint-by-numbers plot mechanics of the second half, not just the pre-ordained "everything is swell now!" ending, but a contrivance involving a fight at the football stadium that serves not a single purpose that couldn't have been dealt with a dozen ways, all of them shorter, and a ginned-up conflict, would absolutely ruin a movie that really, seriously wants to be about how people deal with mental illness; but Movie Star Pictures aren't really serious about anything, and it makes the mechanics a lot easier to ignore. The film's chief reason for being is to entertain, not to enlighten, and while there a lot of limitations on its value as entertainment - the running time, the erratic pace, the reliance on too many scenes of people bellowing at each other (but then, David O. Russell knows from bellowing) - it's still predominately fun and likable. It is not remotely one of the year's best films, but one does best not to expect that kind of thing from an Oscar nominee.

Lo and behold, Silver Linings Playbook does not suck, though it's a far cry from any idea of great storytelling - to say absolutely nothing at all about great cinema - that overlaps with my own to a significant degree. It's the most comfortingly mainstream film yet made by writer-director David O. Russell, a filmmaker whose entire career has been more or less one film after another of finding out exactly how much indie movie spunk he can inject into a largely formulaic scenario before he starts to banish it to the arthouse ghetto; there's less of it here than ever before, although the film certainly announces itself as a Sharp, Tart-Tongued Indie of the '90s tradition where Russell first made his name with Spanking the Monkey and Flirting with Disaster (the latter of which remains, I'd contend, his most overall successful film), what with its wall-to-wall cast of fast talking crazy people being sarcastic, and its signature scene in which the two leads banter over their history of psych medication.

Adapted - with much invention, I am given to understand - from a book by Matthew Quick, the movie positions itself, somewhat effectively, as a successor to the screwball romantic comedies of the 1930s, with bipolar rageagholic Pat Solitano (Cooper) getting sprung from a mental health facility, where he ended up after beating his wife's boyfriend almost to death, by his overweening mother Dolores (Jacki Weaver, whose Supporting Actress Oscar nomination is absolutely inscrutable to me know that I've seen the performance), and taken back to live with her and his unemployed father Pat Sr. (Robert De Niro), presently making ends meet as a bookie. Skip ahead a bit - a lot of a bit, in fact, for unlike the '30s screwballs, Silver Linings Playbook sees no reason to push the pace along at all, and thus do we end up with a 122-minute version of a story almost morally obligated to clock in around 90 - and Pat is repeatedly crossing paths with Tiffany Maxwell (Jennifer Lawrence), sister of his good friend's wife, and like him, dealing with profound emotional difficulties: her latent depression was sent into overdrive when her husband died, and her attempts to self-medicate through sex have left her something of a social pariah. Skip ahead a bit more, and they make a deal: she'll help him circumvent the restraining order his wife has against him by passing letters, if he'll be her partner at a dance competition. Of course, this prickly deal between them, with all the sharp edges of deliberate, willful unlikability both sides invest themselves with, blossoms into romantic attraction, and if you think that's a spoiler, then you don't know enough about movies to deserve to see this one.

It's certainly overstating things to call the script a disaster, though certainly, it's too obviously proud of how insouciant it's being, and has a vastly overrated sense of its own creativity (pro tips: giving a standard-issue Quirky Romantic Comedy a facelift with mental illness, and disguising your Manic Pixie Dream Girl by making her mean, are not creative) and insight into emotionally disordered people. There's some good in it: the family dynamics between the two Pats and the barely-present Dolores have a comfortably intimate level of detail: it's terrifically obvious that these are people who have known each other for years and years before we've seen them, and have a whole host of codes and behaviors that they're all keyed-in to (a particular delight: Dolores's default mode of making "crabby snacks and homemades" as the dining accompaniment to all activities). And if, in general, the characters suffer from the movie version of these mental ailments rather than the actual real-life one (Tiffany's alleged depression, which manifests itself solely when the drama requires it, is a particularly glaring example), at least we're never given any of the usual "sensitive soul who understands a deeper truth and just needs love" bromides in relationship to Pat; indeed, those very tropes are openly mocked in a film quite content to let its characters glower and shout at each other and generally behave like assholes. Loveable assholes, sure; you can't have everything.

Regardless, the script is very much the film's weakness, and everything that works has do so by fighting against it. Russell's direction, alas, does not fight very hard: he gives in to a wholly ineffective impulse to visualise Pat's sped-up mania by using a lot of swift, flowing camera movements, and a sort of ADHD approach to POV (there's a shot fairly early on where, inexplicably, the camera suddenly takes an immediate interest in a close-up of Pat's hands). The performances, across the board, are tetchy and one-note: Bradley Cooper IS manic! Robert De Niro IS short-tempered! Jacki Weaver IS suburban! But even to get to that point requires at least a bit of effort, and it's shocking to this inveterate Cooper-hater to see just how much he's actually able to elevate the material. Better still is Lawrence, saddled with a gruelingly under-written character, a blank slate of female traits written solely to be the sounding board for the real protagonist's journey, and while there has never been an actress alive who could make a truly brilliant character out of that role - even in as well-written a film as Bringing Up Baby, an actress as great as Katharine Hepburn couldn't quite pull it off - Lawrence manages to find something at all to cling to and wrestle up from the depths, suggesting at least that her functional cardboard character is a real flesh-and-blood human.

Cooper and Lawrence both being pretty movie stars actually helps the movie, too, for it changes the battleground on which it's fighting: it makes it a Movie Star Picture, to which we bring a relaxed need for rich psychological authenticity, looking instead for an appealing, entertaining simulacrum of the same. The paint-by-numbers plot mechanics of the second half, not just the pre-ordained "everything is swell now!" ending, but a contrivance involving a fight at the football stadium that serves not a single purpose that couldn't have been dealt with a dozen ways, all of them shorter, and a ginned-up conflict, would absolutely ruin a movie that really, seriously wants to be about how people deal with mental illness; but Movie Star Pictures aren't really serious about anything, and it makes the mechanics a lot easier to ignore. The film's chief reason for being is to entertain, not to enlighten, and while there a lot of limitations on its value as entertainment - the running time, the erratic pace, the reliance on too many scenes of people bellowing at each other (but then, David O. Russell knows from bellowing) - it's still predominately fun and likable. It is not remotely one of the year's best films, but one does best not to expect that kind of thing from an Oscar nominee.