Georgia on my mind

If I describe Julia Loktev's second feature, The Loneliest Planet, as having some of the absolutely best shots of people walking that I have ever seen in a motion picture, I fancy that I have both demonstrated what is the general shape of the movie's appeal, while also demonstrating why that appeal is undoubtedly limited to a tiny and self-selecting audience. Nevertheless, we exist, we folks for whom "the shots of people walking in this movie are extraordinary" is absolutely a statement of sincere, downright enthusiastic praise, and not a joke about art cinema's anti-narrative content. And for us, The Loneliest Planet is cause for celebration. I suspect that you've already figured out which side you'd be prone to fall on, so anything else I can say about the movie would ultimately be redundant. See you later, everybody!

Really, though, for a film in which so aggressively little happens and virtually no words are spoken (and many of those that are, are in un-subtitled Georgian), and which goes to such extremely lengths to obfuscate any possible meaning we could unambiguously pull out of it - really, it's almost a parody of Art Cinema at its Artiest - The Loneliest Planet is an exceptionally thorny and pleasing little behavioral study. Which is not the same thing as a "character study", in that the three human leads of the film don't really earn the title of "characters", though they are consistently and precisely etched by three gifted actors who have very much been thrown into the deep end. The fact, is, we never learn hardly anything about them beyond the barest identifying marks required simply to fashion a working narrative around them; this is the film's most frustrating, alienating element, and also its ballsiest and most respectable. Loktev is not new to this kind of storytelling: her mesmerising narrative debut, 2006's Day Night Day Night, similarly locks us on the outside of a character who spends a lot of time wandering around, and similarly hinges on a single reveal in the middle that very abruptly changes what we think the movie is about. If The Loneliest Planet is an improvement, it is because the relationships played with here are considerably more universal, and the film's depiction of the wilds of Georgia - the ex-Soviet one, not the U.S. one - complicates the narrative more beautifully than Day Night's microscopic vision of New York does. If it is a step down, it is because Loktev's newest feels considerably more contained and systematic as a narrative, and so its refusal to indulge us with any conclusions or clarity don't necessarily register as an artistic choice, but as a hip, chilly pose.

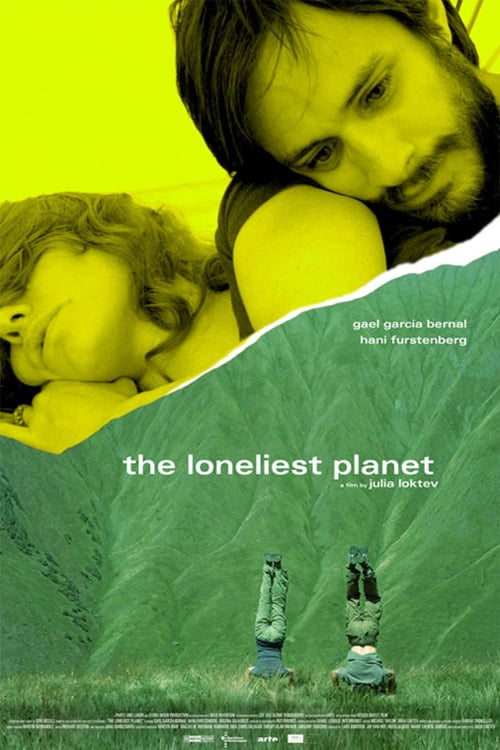

The scenario, because that's really all there is: engaged thirtyish couple Nica (Hani Furstenberg) and Alex (Gael García Bernal), of unclear international extraction, are backpacking through Georgia (the film's title is a snarky reference to the backpacking urban hipster-beloved Lonely Planet travel guides), and have taken on a local guide, Dato (Bidzina Gujabidze) to bring them into the really beautiful, wild parts of the country. The great majority of the film is taken up with the act of hiking through mountains and fields; but there is a single incident of significant note that comes right around the midway point, and in particular there are two consecutive beats in the blocking which slam into you like a hammer to the stomach. I will not spoil it, partially because it's just that good of a moment, and partially because the specifics don't matter; what does matter is that as a result of this incident, Nica and Alex's relationship has been singularly altered, and they spend the rest of the film studiously not talking about it.

What I adore most about The Loneliest Planet - besides the wonderful composition of the walking scenes, of course - is that it's such a tabula rasa for the audience. Really, nothing happens for certain. Maybe the couple's romance has been irrevocably soured, and maybe it hasn't. Maybe the subsequent events of the film are Nica's attempt to punish Alex for his behavior, and maybe they aren't. What is the case, is that as we viewers sitting apart from the characters think about what they've done and try to piece together the reasons why, we're actually evaluating our own value-laden perspective on the sort of pair bond we're watching. It invites reflection, not because Nica and Alex's relationship specifically represent us or anyone we know, I certainly hope, but because they are a heightened variant of the same kind of emotional negotiations that happen in every relationship that has ever been, tarted up with more drama because even an unrelentingly slow and detached movie is still a movie.

In short, the criticism that Nica and Alex are unknowable ciphers, however comfortable their chemistry as a couple, however impeccably performed - that García Bernal is a good fit for this sort of cryptic, elliptical film ought not surprise anybody, but Furstenberg is a real find, bright-eyed and unreadably self-possessed - is fair, but somewhat missing the reason why they are: The Loneliest Planet isn't about their rich and involved backstories, but about how little identifying detail can be given to them, the better to make them stand-ins and and to give their actions a more mythic and symbolic purpose than a psychological one. Which is, I suspect, another phrase that tips one off to the sort of the crowd the film appeals to.

In the midst of all this, Loktev and cinematographer Inti Briones do a lot of showing off - the Georgian countryside is, basically, the most beautiful place in the history of time, according to this movie - but The Loneliest Planet is never, ever just an excuse for lush landscape photography: it's an alarmingly, gloriously visual movie, in fact, and the very same lushness of those landscapes, captured in expansive long shots where the characters are bare dots against the background, and in shots where it is indistinctly visible over their shoulders, and everything in between. This doesn't always serve an entirely clear purpose, though the sense of the characters being swallowed up by a beautiful but essentially inhuman wilderness certainly adds a welcome note of atmosphere, and the way that the characters are typically shown to be physical interruptions of the landscapes (Nica's flaming red hair, a dramatic contrast to the almost non-stop greens of the environment, is an especially overt example) nicely underlines the feeling that they are inauthentic in some way, and this plays out in all sorts of interesting little moments throughout the film.

And, of course, the framing of those shots of people walking: using the Z-axis with a clear, steady thematic intent like you hardly ever see, in which the relationships between the characters and each other, and between them and the camera, represents a constant fluctuation of the emotional tenor of the story to that point, such that you could make a decent stab at decoding the entire film's narrative just by watching the sideways tracking shots.

Meanwhile, the soundtrack fairly blasts your ears with natural noises, and a droning trance music soundtrack that frequently cuts off with jarring suddenness - really, the whole soundscape is jarring, from the pounding, panting sounds we hear over black (possibly a deliberate feint: it sounds like sex, but it's just Nica jumping on a trampoline, unsexily naked), to the in-context shattering noises of a tent being folded up that plays over the credits. Like the visuals, the hyper-real, "this is nature" aesthetic serves mainly to draw our attention to the inherent unnaturalism of the rest of the movie.

An intellectual exercise? Hell yes. Sometimes you need a good intellectual exercise, though, and The Loneliest Planet is a great one. I don't suppose there's any possible way to express enthusiasm for it and all its unanswerable dead ends without sounding smugly pretentious, but that's a risk I'll run: it struck me as being more innovative, challenging, and most importantly, interesting than most of what I saw in 2012, and that's worth praising no matter what.

Really, though, for a film in which so aggressively little happens and virtually no words are spoken (and many of those that are, are in un-subtitled Georgian), and which goes to such extremely lengths to obfuscate any possible meaning we could unambiguously pull out of it - really, it's almost a parody of Art Cinema at its Artiest - The Loneliest Planet is an exceptionally thorny and pleasing little behavioral study. Which is not the same thing as a "character study", in that the three human leads of the film don't really earn the title of "characters", though they are consistently and precisely etched by three gifted actors who have very much been thrown into the deep end. The fact, is, we never learn hardly anything about them beyond the barest identifying marks required simply to fashion a working narrative around them; this is the film's most frustrating, alienating element, and also its ballsiest and most respectable. Loktev is not new to this kind of storytelling: her mesmerising narrative debut, 2006's Day Night Day Night, similarly locks us on the outside of a character who spends a lot of time wandering around, and similarly hinges on a single reveal in the middle that very abruptly changes what we think the movie is about. If The Loneliest Planet is an improvement, it is because the relationships played with here are considerably more universal, and the film's depiction of the wilds of Georgia - the ex-Soviet one, not the U.S. one - complicates the narrative more beautifully than Day Night's microscopic vision of New York does. If it is a step down, it is because Loktev's newest feels considerably more contained and systematic as a narrative, and so its refusal to indulge us with any conclusions or clarity don't necessarily register as an artistic choice, but as a hip, chilly pose.

The scenario, because that's really all there is: engaged thirtyish couple Nica (Hani Furstenberg) and Alex (Gael García Bernal), of unclear international extraction, are backpacking through Georgia (the film's title is a snarky reference to the backpacking urban hipster-beloved Lonely Planet travel guides), and have taken on a local guide, Dato (Bidzina Gujabidze) to bring them into the really beautiful, wild parts of the country. The great majority of the film is taken up with the act of hiking through mountains and fields; but there is a single incident of significant note that comes right around the midway point, and in particular there are two consecutive beats in the blocking which slam into you like a hammer to the stomach. I will not spoil it, partially because it's just that good of a moment, and partially because the specifics don't matter; what does matter is that as a result of this incident, Nica and Alex's relationship has been singularly altered, and they spend the rest of the film studiously not talking about it.

What I adore most about The Loneliest Planet - besides the wonderful composition of the walking scenes, of course - is that it's such a tabula rasa for the audience. Really, nothing happens for certain. Maybe the couple's romance has been irrevocably soured, and maybe it hasn't. Maybe the subsequent events of the film are Nica's attempt to punish Alex for his behavior, and maybe they aren't. What is the case, is that as we viewers sitting apart from the characters think about what they've done and try to piece together the reasons why, we're actually evaluating our own value-laden perspective on the sort of pair bond we're watching. It invites reflection, not because Nica and Alex's relationship specifically represent us or anyone we know, I certainly hope, but because they are a heightened variant of the same kind of emotional negotiations that happen in every relationship that has ever been, tarted up with more drama because even an unrelentingly slow and detached movie is still a movie.

In short, the criticism that Nica and Alex are unknowable ciphers, however comfortable their chemistry as a couple, however impeccably performed - that García Bernal is a good fit for this sort of cryptic, elliptical film ought not surprise anybody, but Furstenberg is a real find, bright-eyed and unreadably self-possessed - is fair, but somewhat missing the reason why they are: The Loneliest Planet isn't about their rich and involved backstories, but about how little identifying detail can be given to them, the better to make them stand-ins and and to give their actions a more mythic and symbolic purpose than a psychological one. Which is, I suspect, another phrase that tips one off to the sort of the crowd the film appeals to.

In the midst of all this, Loktev and cinematographer Inti Briones do a lot of showing off - the Georgian countryside is, basically, the most beautiful place in the history of time, according to this movie - but The Loneliest Planet is never, ever just an excuse for lush landscape photography: it's an alarmingly, gloriously visual movie, in fact, and the very same lushness of those landscapes, captured in expansive long shots where the characters are bare dots against the background, and in shots where it is indistinctly visible over their shoulders, and everything in between. This doesn't always serve an entirely clear purpose, though the sense of the characters being swallowed up by a beautiful but essentially inhuman wilderness certainly adds a welcome note of atmosphere, and the way that the characters are typically shown to be physical interruptions of the landscapes (Nica's flaming red hair, a dramatic contrast to the almost non-stop greens of the environment, is an especially overt example) nicely underlines the feeling that they are inauthentic in some way, and this plays out in all sorts of interesting little moments throughout the film.

And, of course, the framing of those shots of people walking: using the Z-axis with a clear, steady thematic intent like you hardly ever see, in which the relationships between the characters and each other, and between them and the camera, represents a constant fluctuation of the emotional tenor of the story to that point, such that you could make a decent stab at decoding the entire film's narrative just by watching the sideways tracking shots.

Meanwhile, the soundtrack fairly blasts your ears with natural noises, and a droning trance music soundtrack that frequently cuts off with jarring suddenness - really, the whole soundscape is jarring, from the pounding, panting sounds we hear over black (possibly a deliberate feint: it sounds like sex, but it's just Nica jumping on a trampoline, unsexily naked), to the in-context shattering noises of a tent being folded up that plays over the credits. Like the visuals, the hyper-real, "this is nature" aesthetic serves mainly to draw our attention to the inherent unnaturalism of the rest of the movie.

An intellectual exercise? Hell yes. Sometimes you need a good intellectual exercise, though, and The Loneliest Planet is a great one. I don't suppose there's any possible way to express enthusiasm for it and all its unanswerable dead ends without sounding smugly pretentious, but that's a risk I'll run: it struck me as being more innovative, challenging, and most importantly, interesting than most of what I saw in 2012, and that's worth praising no matter what.