The sea inside

Finding Dory is definitely the best sequel made by Pixar Animation Studios without the word "toy" in the title. This is a relief, but not all that much of an achievement: Cars 2 is a visually ravishing trash fire, while Monsters University is an easy-going, wildly lazy hang-out movie that only turns on its brain for the final act. Improving on those two doesn't take a whole lot, and sadly, that's just about all that Finding Dory offers. It's firmly in Pixar's "well that didn't quite work, but it was a great try!" tier, alongside Brave and The Good Dinosaur, and if I like it less than either of them, that's because the strain of being a sequel gives it a much harder time than those films' incomplete character development and world-building.

Which isn't to say it's a washout, or anything, and for the first few minutes, you might even be able to mistake it for a masterpiece. The opening is a flashback to the childhood of Dory (Sloane Murray), a blue tang fish with chronic short-term memory loss, being enthusiastically coached and aided by her parents, Jenny (Diane Keaton) and Charlie (Eugene Levy). It is a charming, sweet snapshot of life of how coping with a mental disability works in a tight-knit, supportive family, with Keaton and Levy providing heartbreakingly warm and parental vocal delivery (things I did not expect to learn in life: Eugene Levy saying "cupcake" could make my eyes tear up). The juvenile Dory character model is also perversely, obscenely cute, made up almost nothing but eyes and a tail. And as storytelling, this sequence is crisp and efficient, laying out what we need to know about the characters and their feelings, telescoping time through a series of whip-smart edits that show how Dory was, after a certain point, swept away by an undertow and left to fend for herself in the wide ocean, on a constant hunt to find her parents, even after her compromised memory and years of loneliness, she's forgotten who she was looking for, or why.

And then this not-quite-a-montage wraps itself up with a scene from Dory's perspective (she's by this point voiced by Ellen DeGeneres), in which a speedboat races by over the surface of the water, chased by a terrified clownfish named Marlin (Albert Brooks). He asks about the boat, and she volunteers to lead him, and the scene just kind of dissolves into nothingness. Most of the audience has seen this film's 2003 predecessor, Finding Nemo, so we all know what's going on in this moment, but it is extraordinarily artless and clunky. Nor is it necessary: a straight cut from lost child Dory to adult Dory at the time of the film's present (one year after the events of Finding Nemo) would get the same job done while still trading on the viewer's knowledge of the earlier film. It was, at any rate, the first time I was shocked out of the movie, right there in the theater, with the awareness of how crudely Dory had just called back to Nemo, disrupting its own narrative integrity for no gain. I am sorry to report that it was not the last time I had this feeling.

The body of the movie plays out, for the most part, as themes and variations on Finding Nemo - close enough that you can map a lot of the beats onto the earlier film, far enough that it doesn't come across as a pure retread. Dory has an unexpected flash of a memory - just enough to start to figure out where she might have lost her parents so long ago, and instantly sets off to find them, with Marlin and his son Nemo (Hayden Rolence) in tow. Hitching a ride with the turtles who featured into the last film, they cross the Pacific in hardly the blink of an eye - one of the more prominent missteps in the new movie, given what a film-length ordeal it was just to round the east coast of Australia last time - the trio ends up at the Marine Life Institute in Morro Bay, California. Accident causes Dory to end up inside the Institute, still questing to find her parents, while Marlin and Nemo work to find their way inside to rescue her. It lacks for the grandeur of Nemo's exploration of the ocean, stretching out to the edges of the frame, but I think the limited scale works to Dory's favor: it creates a different kind of environment to explore, and generally more interesting physical challenges for the characters to overcome.

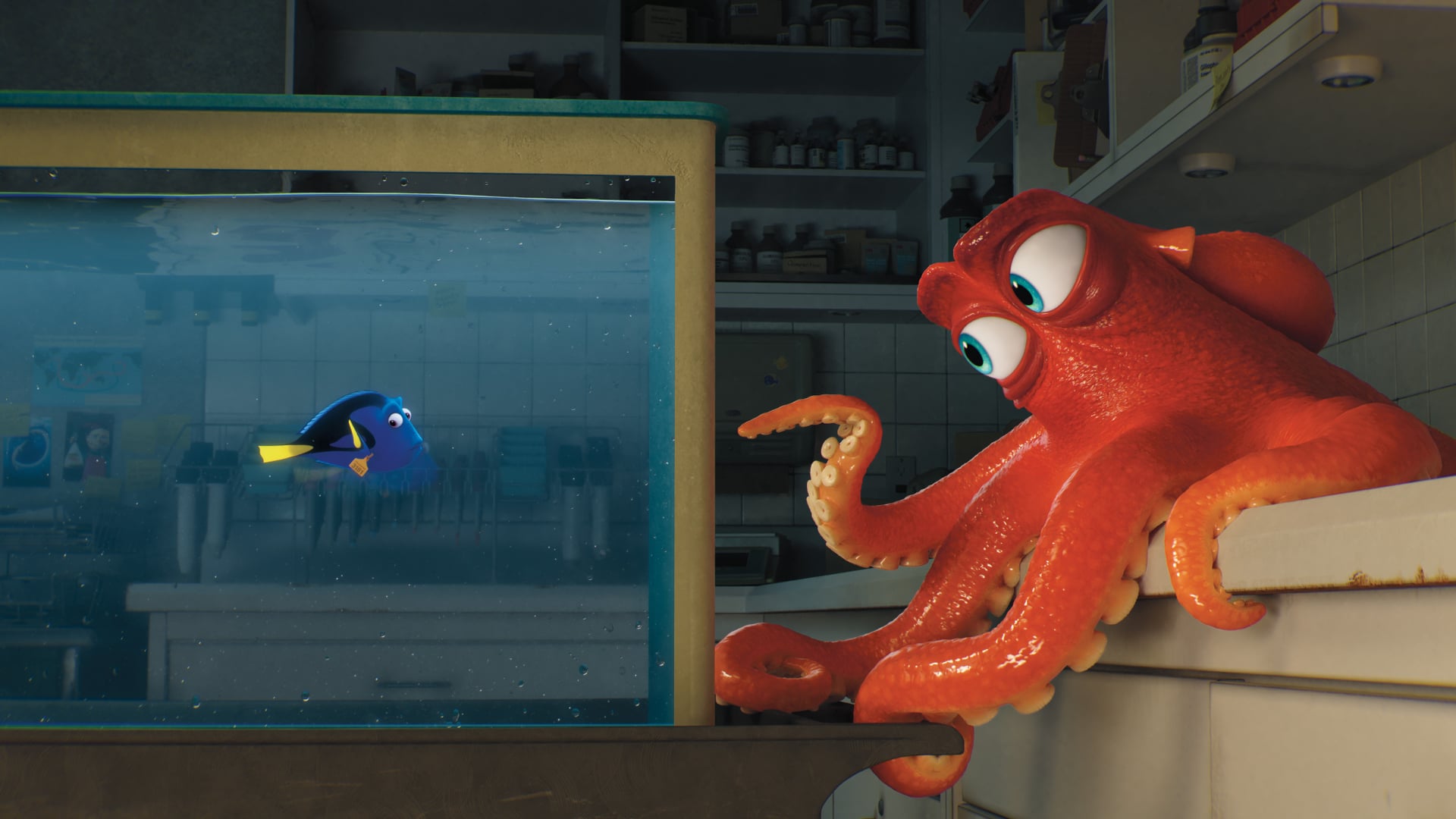

Insofar as Finding Dory follows Dory's attempt to navigate the Institute, it's a mostly charming adventure-comedy. The film's new set of characters aren't quite at the top of the scale for sidekicks in Pixar movies, but they're pretty delightful company: Destiny the whale shark (Kaitlin Olson) - the screenplay by director Andrew Stanton and Victoria Strouse, undoubtedly with contributions from dozens of people inside Pixar doesn't seem to be aware that whale sharks are sharks, not whales, alas - and Bailey the beluga (Ty Burrell) are good-natured additions to the film's "with help and support, you can overcome your physical limitations" message, as well as charmingly-designed figures (Destiny seems purposefully built to be the model for an oversized plush toy). The new star, no question, is Hank the seven-armed octopus, a paranoid, skulking sort played with maximum crabby old man sharpness by Ed O'Neill, and subject to an inventive array of gags involving octopodes' ability to change color to blend into their backgrounds, stretched to exaggerated ends. Dory's chase through the pipes and displays of the Institute to find what happened to her blue tang clan never rises above the level of "delightful kids' movie shenanigans" - but it is delightful, and then some.

Meanwhile, the film frequently checks in with Marlin and Nemo, and it dies there. It's not that the animation is weaker, nor the gag construction (there's a great scene involving a fountain spitting jets of water, this film's version of the jellyfish forest from Nemo), and through this subplot we get to meet another set of wonderful new characters - Fluke (Idris Elba) and Rudder (Dominic West), a pair of territorial sea lions who draw from the "mine! mine!" seagulls in Nemo while adding a level of low-rent London gangster comedy, and the frazzled, unspeaking, possibly psychotic common loon Becky. We also have to cope with how badly this film fucks up Marlin and Nemo, and how unpleasant it is to spend any time with them. The problem is one of balancing tones: in Finding Nemo, Marlin was the straight man, and Dory was the comic relief. Now that Dory has been elevated to straight man status, Marlin fills the roll of comic relief, except he's still a straight man, which gives his character no particular function. Beyond that, his personality has been rolled back from the last film: he's neurotic and overprotective again, this time with a weird bullying streak. Nemo's solitary function, meanwhile, is to be a humorless moral scold, glowering at Marlin constantly. All the time spent with Marlin and Nemo is time wasted, even when it's in support of decent comedy.

The need to force Marlin into Finding Dory is the worst thing about it as sequel, and probably also the most inevitable. In general, the film is too anxious to incorporate characters from last time, even when they don't fit (though the post-credits scene, which serves no other purpose than to do exactly this, is a marvel), and Marlin is the worst of it - not that he couldn't fit into the new film's story, but that all of the choices made by the filmmakers ensure that he doesn't. It's terribly for Finding Dory's pace, for its comedy, even for its emotional appeal, given how one-note and shrill all of of the Marlin/Nemo scenes are, and how much the detract from the none-too-penetrating sentiment of the Dory scenes.

It is disappointing that Stanton of all people should be responsible for this mismanagement of rhythm and mood: WALL·E has some of the finest blending of raw emotion with chase-based comedy in Pixar's stable, and it's the thing Finding Dory does worst. Its big thriller finale is gaudy and overdone, and by the time the slow-motion and Louis Armstrong kick in, it feels like we're watching something much too cheap to be graced with even the now-tarnished Pixar brand name; and while DeGeneres does a fine job of rebooting the character to be a sentimental lead (though I think she did better at letting hints of tragedy sneak out of the clowning around she did in the first film), there's not much that positions this film to be have the richness of feeling that used to be Stanton's great strength.

None of which is to say that Finding Dory is a failure - it's immensely likable and sincere, and often very funny - the sea lions are terrific, and real-life actor Sigourney Weaver is turned into a thoroughly unexpected running joke that keeps paying off no matter how many how times the screenplay revisits it. Its contrivances and violations of biology and good sense (which are many) come across in the spirit of good fun, and it's beautiful to look at, of course - not as creative as Inside Out nor as vivid as The Good Dinosaur, but there's nothing in here to risk Pixar's status as the most technically accomplished animation studio in the world. It's a safe movie, though, one too-obviously calculated to hit its marks as a sequel, and while I think that Stanton and company did a fine job of exploring new territory with this film, I also don't believe for a second that the story preceded the marketing impetus.

Which isn't to say it's a washout, or anything, and for the first few minutes, you might even be able to mistake it for a masterpiece. The opening is a flashback to the childhood of Dory (Sloane Murray), a blue tang fish with chronic short-term memory loss, being enthusiastically coached and aided by her parents, Jenny (Diane Keaton) and Charlie (Eugene Levy). It is a charming, sweet snapshot of life of how coping with a mental disability works in a tight-knit, supportive family, with Keaton and Levy providing heartbreakingly warm and parental vocal delivery (things I did not expect to learn in life: Eugene Levy saying "cupcake" could make my eyes tear up). The juvenile Dory character model is also perversely, obscenely cute, made up almost nothing but eyes and a tail. And as storytelling, this sequence is crisp and efficient, laying out what we need to know about the characters and their feelings, telescoping time through a series of whip-smart edits that show how Dory was, after a certain point, swept away by an undertow and left to fend for herself in the wide ocean, on a constant hunt to find her parents, even after her compromised memory and years of loneliness, she's forgotten who she was looking for, or why.

And then this not-quite-a-montage wraps itself up with a scene from Dory's perspective (she's by this point voiced by Ellen DeGeneres), in which a speedboat races by over the surface of the water, chased by a terrified clownfish named Marlin (Albert Brooks). He asks about the boat, and she volunteers to lead him, and the scene just kind of dissolves into nothingness. Most of the audience has seen this film's 2003 predecessor, Finding Nemo, so we all know what's going on in this moment, but it is extraordinarily artless and clunky. Nor is it necessary: a straight cut from lost child Dory to adult Dory at the time of the film's present (one year after the events of Finding Nemo) would get the same job done while still trading on the viewer's knowledge of the earlier film. It was, at any rate, the first time I was shocked out of the movie, right there in the theater, with the awareness of how crudely Dory had just called back to Nemo, disrupting its own narrative integrity for no gain. I am sorry to report that it was not the last time I had this feeling.

The body of the movie plays out, for the most part, as themes and variations on Finding Nemo - close enough that you can map a lot of the beats onto the earlier film, far enough that it doesn't come across as a pure retread. Dory has an unexpected flash of a memory - just enough to start to figure out where she might have lost her parents so long ago, and instantly sets off to find them, with Marlin and his son Nemo (Hayden Rolence) in tow. Hitching a ride with the turtles who featured into the last film, they cross the Pacific in hardly the blink of an eye - one of the more prominent missteps in the new movie, given what a film-length ordeal it was just to round the east coast of Australia last time - the trio ends up at the Marine Life Institute in Morro Bay, California. Accident causes Dory to end up inside the Institute, still questing to find her parents, while Marlin and Nemo work to find their way inside to rescue her. It lacks for the grandeur of Nemo's exploration of the ocean, stretching out to the edges of the frame, but I think the limited scale works to Dory's favor: it creates a different kind of environment to explore, and generally more interesting physical challenges for the characters to overcome.

Insofar as Finding Dory follows Dory's attempt to navigate the Institute, it's a mostly charming adventure-comedy. The film's new set of characters aren't quite at the top of the scale for sidekicks in Pixar movies, but they're pretty delightful company: Destiny the whale shark (Kaitlin Olson) - the screenplay by director Andrew Stanton and Victoria Strouse, undoubtedly with contributions from dozens of people inside Pixar doesn't seem to be aware that whale sharks are sharks, not whales, alas - and Bailey the beluga (Ty Burrell) are good-natured additions to the film's "with help and support, you can overcome your physical limitations" message, as well as charmingly-designed figures (Destiny seems purposefully built to be the model for an oversized plush toy). The new star, no question, is Hank the seven-armed octopus, a paranoid, skulking sort played with maximum crabby old man sharpness by Ed O'Neill, and subject to an inventive array of gags involving octopodes' ability to change color to blend into their backgrounds, stretched to exaggerated ends. Dory's chase through the pipes and displays of the Institute to find what happened to her blue tang clan never rises above the level of "delightful kids' movie shenanigans" - but it is delightful, and then some.

Meanwhile, the film frequently checks in with Marlin and Nemo, and it dies there. It's not that the animation is weaker, nor the gag construction (there's a great scene involving a fountain spitting jets of water, this film's version of the jellyfish forest from Nemo), and through this subplot we get to meet another set of wonderful new characters - Fluke (Idris Elba) and Rudder (Dominic West), a pair of territorial sea lions who draw from the "mine! mine!" seagulls in Nemo while adding a level of low-rent London gangster comedy, and the frazzled, unspeaking, possibly psychotic common loon Becky. We also have to cope with how badly this film fucks up Marlin and Nemo, and how unpleasant it is to spend any time with them. The problem is one of balancing tones: in Finding Nemo, Marlin was the straight man, and Dory was the comic relief. Now that Dory has been elevated to straight man status, Marlin fills the roll of comic relief, except he's still a straight man, which gives his character no particular function. Beyond that, his personality has been rolled back from the last film: he's neurotic and overprotective again, this time with a weird bullying streak. Nemo's solitary function, meanwhile, is to be a humorless moral scold, glowering at Marlin constantly. All the time spent with Marlin and Nemo is time wasted, even when it's in support of decent comedy.

The need to force Marlin into Finding Dory is the worst thing about it as sequel, and probably also the most inevitable. In general, the film is too anxious to incorporate characters from last time, even when they don't fit (though the post-credits scene, which serves no other purpose than to do exactly this, is a marvel), and Marlin is the worst of it - not that he couldn't fit into the new film's story, but that all of the choices made by the filmmakers ensure that he doesn't. It's terribly for Finding Dory's pace, for its comedy, even for its emotional appeal, given how one-note and shrill all of of the Marlin/Nemo scenes are, and how much the detract from the none-too-penetrating sentiment of the Dory scenes.

It is disappointing that Stanton of all people should be responsible for this mismanagement of rhythm and mood: WALL·E has some of the finest blending of raw emotion with chase-based comedy in Pixar's stable, and it's the thing Finding Dory does worst. Its big thriller finale is gaudy and overdone, and by the time the slow-motion and Louis Armstrong kick in, it feels like we're watching something much too cheap to be graced with even the now-tarnished Pixar brand name; and while DeGeneres does a fine job of rebooting the character to be a sentimental lead (though I think she did better at letting hints of tragedy sneak out of the clowning around she did in the first film), there's not much that positions this film to be have the richness of feeling that used to be Stanton's great strength.

None of which is to say that Finding Dory is a failure - it's immensely likable and sincere, and often very funny - the sea lions are terrific, and real-life actor Sigourney Weaver is turned into a thoroughly unexpected running joke that keeps paying off no matter how many how times the screenplay revisits it. Its contrivances and violations of biology and good sense (which are many) come across in the spirit of good fun, and it's beautiful to look at, of course - not as creative as Inside Out nor as vivid as The Good Dinosaur, but there's nothing in here to risk Pixar's status as the most technically accomplished animation studio in the world. It's a safe movie, though, one too-obviously calculated to hit its marks as a sequel, and while I think that Stanton and company did a fine job of exploring new territory with this film, I also don't believe for a second that the story preceded the marketing impetus.