A review in brief

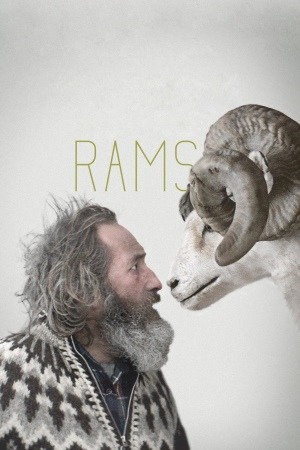

I would say, "once you've seen one Icelandic domestic comedy-drama, you've seen 'em all", but perhaps that's making very wrong assumptions about the English-speaking cinephile's consumption habits. Still, the point stands. Grímur Hákonarson's Rams, winner of the Prix Un Certain Regard at the 2015 Cannes Film Festival, has a great many things about it that are more than worthy of the utmost praise. None of them, however, are the unexpected thing, and the only point at which the film veers into the unpredictable is with a, well, predictably mordant European Art Film™ ending, the kind that catches you off guard more because it is so damned anxious to be anti-commercial than because it necessarily follows.

For all that, let's accentuate the positive: I thoroughly enjoyed Rams, maybe even more than I enjoyed last year's Icelandic dramedy coming off a hot film fest run, Of Horses and Men. It's less singular, but its one-track focus arguably gives it more insight. The setting is a nearly hermetically-sealed valley populated chiefly by sheep ranchers; the film's opening sequence gives us a nice little snapshot of how these people live and thrive in their remote, self-perpetuating enclave, with prizes being given out for the year's best shepherding among a half-dozen people who all clearly know each other, in what appears to be the only room in what appears to be the only bar necessary for the community. It's dry, whimsical, and completely heartfelt - a glimpse into the hearts and minds of Colorful Locals that leaves us emotionally invested in the community by the 10-minute mark.

The plot itself hinges on a pair of brothers and next-door neighbors, Gummi (Sigurður Sigurjónsson) and Kiddi (Theodór Júlíusson), who have steadily nursed an unspeaking hate for the last 40 years; they are forcibly made allies when a case of scrapie breaks out in the valley, which means that in short order, every single ram and sheep in that very close-knit, self-sustaining community must be destroyed. As the oldest and most cantankerous inhabitants of the valley, Gummi and Kiddi are the most angered by this change, and uncomfortably band together to resist it however they might.

Rams sure does look like a comedy; it sure isn't one. Besides its arguably overdetermined ending, the most memorable pieces of it are the most sorrowful: the sense of crushing gravity that comes about when one of the characters prepares to kill his sheep as a sign of his love and respect for the animals, a slow-pacd and ritualistic scene that leaves the physical violence entirely offscreen, focusing all its attention on the emotional violence. The quirkiness that seems omnipresent in much of the film falls away to reveal something hard and brutally meaningful in moments like those, deftly played by the actors in a highly limited, minimal way that's focused on action and behavior, almost Hemingway-like in their attention to surfaces, which means that the few open expressions of feeling are far more potent than they could be. There's nothing as-such "fresh" about anything here, but it's a beautifully well-executed variant on a stock form.

For all that, let's accentuate the positive: I thoroughly enjoyed Rams, maybe even more than I enjoyed last year's Icelandic dramedy coming off a hot film fest run, Of Horses and Men. It's less singular, but its one-track focus arguably gives it more insight. The setting is a nearly hermetically-sealed valley populated chiefly by sheep ranchers; the film's opening sequence gives us a nice little snapshot of how these people live and thrive in their remote, self-perpetuating enclave, with prizes being given out for the year's best shepherding among a half-dozen people who all clearly know each other, in what appears to be the only room in what appears to be the only bar necessary for the community. It's dry, whimsical, and completely heartfelt - a glimpse into the hearts and minds of Colorful Locals that leaves us emotionally invested in the community by the 10-minute mark.

The plot itself hinges on a pair of brothers and next-door neighbors, Gummi (Sigurður Sigurjónsson) and Kiddi (Theodór Júlíusson), who have steadily nursed an unspeaking hate for the last 40 years; they are forcibly made allies when a case of scrapie breaks out in the valley, which means that in short order, every single ram and sheep in that very close-knit, self-sustaining community must be destroyed. As the oldest and most cantankerous inhabitants of the valley, Gummi and Kiddi are the most angered by this change, and uncomfortably band together to resist it however they might.

Rams sure does look like a comedy; it sure isn't one. Besides its arguably overdetermined ending, the most memorable pieces of it are the most sorrowful: the sense of crushing gravity that comes about when one of the characters prepares to kill his sheep as a sign of his love and respect for the animals, a slow-pacd and ritualistic scene that leaves the physical violence entirely offscreen, focusing all its attention on the emotional violence. The quirkiness that seems omnipresent in much of the film falls away to reveal something hard and brutally meaningful in moments like those, deftly played by the actors in a highly limited, minimal way that's focused on action and behavior, almost Hemingway-like in their attention to surfaces, which means that the few open expressions of feeling are far more potent than they could be. There's nothing as-such "fresh" about anything here, but it's a beautifully well-executed variant on a stock form.

Categories: comedies, domestic dramas, scandinavian cinema