We're all mad here

Dedicated to Hollywood icon Olivia de Havilland on her 100th birthday

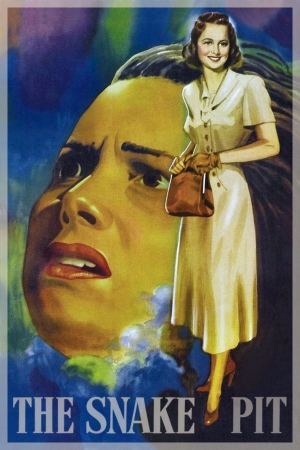

Speaking honestly, The Snake Pit, released in 1948, is kind of a bad movie. It's a thick slab of 20th Century Fox Post-War Message Movie, and if it remains more watchable than the previous year's Gentleman's Agreement, that's only because every movie in history is more watchable than Gentleman's Agreement. What we have here is a film that passionately believes in what it's telling us, so passionate that it eschews things like dignity or intellect in getting to its message. It's the mostly plotless story of a woman's hellish months in a mental hospital: Virginia Stuart Cunningham (Olivia de Havilland) suffers from a catch-all case of "sickness", and over the course of her stay in a New York asylum, she is treated with care by some doctors and nurses, but disrespected and abused by others, all while receiving regular visits from the husband (Mark Stevens) that she frequently fails to recognise. The film is a cry for understanding the difficulty of treating these diseases, and asking us to think of those with mental disorders as people to be cared for rather than dumped into the memory whole. It's also an exposé of the horrendous condition of mental hospitals in the United States in the 1940s, and clearly an effective one, in a very measurable way: as a result of the public outcry stemming from this film's release, several states passed legislation changing the way state-run mental hospitals were operated (Fox trumpeted that it was 26 states, which is perhaps an exaggerated number, but it was at least some, and some is impressive enough). But real-world effectiveness, laudable and worthy of celebration though it may be, is a different thing than aesthetic effectiveness, and here's where I'm not quite sure what to do with The Snake Pit.

It's a film torn about the way it wants to approach its material. On the one hand, it is heavily realistic: one of the most realistic productions in Hollywood up to that point, in fact. Director Anatole Litvak, who'd spent World War II contributing to Frank Capra's Why We Fight documentaries for the U.S. military, had some downright revolutionary ideas (by Hollywood standards) for how to strip out the glowing polish of The Movies from his cine-journalism. The most self-evident of these ideas was to reduce or outright eliminate the use of makeup for his nearly all-woman cast, or using makeup to cause de Havilland, to look more wired and gaunt. For that matter, de Havilland also went on a crash diet, to reduce her slender frame and suck even more of the vitality from her face. I have not done the proper research on the matter, but I suspect that de Havilland's performance might be the first time a Hollywood star "de-glammed" to seem more, like, real, man. And in a fine prophecy of what would happen to gorgeous women like Grace Kelly and Charlize Theron, de Havilland nabbed an Oscar nomination for her work (she lost, unfairly, despite being leaps and bounds the stand-out in one of the weakest Best Actress competitions in Academy history - one with Ingrid Bergman, Irene Dunne, and Barbara Stanwyck, no less, all giving some of the worst performances of their careers).

All of which is well and good, but there's a tension running throughout The Snake Pit, where it seems like the people involved in making it hadn't quite figured out what "realism" meant. There's some titanically overbaked nonsense littering the whole film, mostly to do with the depiction of the undifferentiated "sickness" that all of the women onscreen seem to suffer from. It is of course unfair to slag a movie from 1948 for being insufficiently sophisticated about what mental illness looked like, but surely even then, they knew better than this? This screaming, preening, chewing lips and glaring like a terrified deer? At times, it seems like Litvak secretly wishes he was directing a sudsy Susan Hayward dispsomania thriller instead of this very concerned prestige drama, with cinematographer Leo Tover obligingly lighting much of the film like a noir rather than a depiction of allegedly real-world spaces. Litvak also pushes the actors to places that I frankly don't think suit them very well, the leading lady least of all.

Even granting that, de Havilland does as much as she can with what she's given. There are some conceits in Frank Partos and Millen Brand's screenplay, adapted from Mary Jane Ward's celebrated 1946 novel, that are simply beyond redemption: worst among these is the insistence on providing Virginia's interior monologue as she slides from relative lucidity to utter fogginess, and as she tries to hide her weakness from the doctors, while de Havilland pantomimes the feelings she recites to us in voice-over. These moments are ludicrous and terrible. As much as possible, however, the actor tries to synthesise the two strands of the movie into one internally coherent character: treating Virginia's internal confusion with as much gravity as she can, fully inhabiting the all-encompassing sense of fear that the character feels even without knowing, at all points, why she's afraid; at times, that fear bubbles out, and it's here that de Havilland gives into the melodramatic necessities that the film demands, trying as much as possible to suggest that it's the character at a breaking point rather than just the Crazy Lady Going Crazy, which far too much of the screenplay would seem to make the most obvious way to play entire scenes.

It's not to say that de Havilland is waging a single-front war against The Snake Pit sliding into tacky camp. This is more a case of a screenplay making very poor judgments and a director running with them, in the context of a mostly solid depiction of a specific place, rather than an inherently corrupt piece of writing. Some of the most frustrating aspects of the movie aren't even really its fault; the implication that psychoanalysis can cure schizophrenia, a horrifying lesson if ever there was one, really was at the forefront of mental health at the time the movie was made, in the days when Freudian psychoanalysis hadn't lost any of its luster - indeed, was more popular than it had been in Freud's own time. It is unfair to accuse the movie of furthering a cartoonish understanding of how people with mental disorders act and function when it was just about the first movie to treat those disorders as a series topic, and when the cutting edge of science still didn't have a good sense of what the hell was going on inside these people's heads. And if we take The Snake Pit on those terms - a depiction of what mental health treatment in 1948 looked like from the perspective of 1948 - it's a much more tolerable experience, if still tonally dysfuncational.

The "you are there" approach to showcasing the inside of the asylum through one of its patients rather than through the doctors is fruitful for the movie, filling it with a sense of arbitrary, unfair, and frightening stimuli. The shift in mood from the kind (if patronising) treatment of Dr. Kik (Leo Genn) to the barking nastiness of Nurse Davis (Helen Craig) effectively suggests Virginia's sense of being lost and in a whirlwind; the nothing-held-back performances of the supporting cast playing the patients generally work to etch out different kinds of mental imbalance even if the writing doesn't. The face-off between Virginia and a haughty woman played by Beulah Bondi, who fancies herself the wealthiest and most beautiful of women, provides for an exciting acting showcase as de Havilland and Bondi lie to each other in strategic ways, even if it's not terribly insightful as drama.

Anyways, whatever limitations the film has, it's a monumental showcase for de Havilland; it's the performance from her career that impresses me the most, even if it's not the most flawlessly consistent. Coming just a few years into the period after she successfully broke her Warner Bros. contract and became Hollywood's first independent movie star, The Snake Pit is every bit the project that an actor who'd been stalled out in a bunch of delicate flower roles like Melanie in Gone with the Wind does when she wants to prove that she's got plenty of other tricks up her sleeve. If her 1946 Oscar-winning turn in To Each His Own first demonstrated that she could be anything other than a saint (while dragging her performance down with an even more tonally inept screenplay than this one), it's in The Snake Pit that we first see an actively unpleasant de Havilland, as she exudes paranoid mistrust of the people around her, manifesting in sour facial expressions and angry, snappish line deliveries flowing in and out of sweeter modes. Though in this film, even the sweetness feels like a put on, de Havilland suggesting that Virginia is trying to adopt a pleasant purity that she doesn't feel as a defense against confusion and abuse. It's not always clear that the actor has quite traced why her character moves from one mode to the next, but the closer we get to the end, the more precise and coherent her character creation is, drawing moments together into a singular momentum. So perhaps what looks like sloppiness in the early going is really just strategy: de Havilland suggesting Virginia's lack of consistent self-definition so that the contrast when she starts to be able to stick to a single, concrete internal narrative is clearer. It's probably all just in service to a script that hasn't completely cracked the way to depict a mental disorder it plainly doesn't understand, but de Havilland's bravura performance has enough force to push the whole project along even when its script is stuck in a tailspin.

Speaking honestly, The Snake Pit, released in 1948, is kind of a bad movie. It's a thick slab of 20th Century Fox Post-War Message Movie, and if it remains more watchable than the previous year's Gentleman's Agreement, that's only because every movie in history is more watchable than Gentleman's Agreement. What we have here is a film that passionately believes in what it's telling us, so passionate that it eschews things like dignity or intellect in getting to its message. It's the mostly plotless story of a woman's hellish months in a mental hospital: Virginia Stuart Cunningham (Olivia de Havilland) suffers from a catch-all case of "sickness", and over the course of her stay in a New York asylum, she is treated with care by some doctors and nurses, but disrespected and abused by others, all while receiving regular visits from the husband (Mark Stevens) that she frequently fails to recognise. The film is a cry for understanding the difficulty of treating these diseases, and asking us to think of those with mental disorders as people to be cared for rather than dumped into the memory whole. It's also an exposé of the horrendous condition of mental hospitals in the United States in the 1940s, and clearly an effective one, in a very measurable way: as a result of the public outcry stemming from this film's release, several states passed legislation changing the way state-run mental hospitals were operated (Fox trumpeted that it was 26 states, which is perhaps an exaggerated number, but it was at least some, and some is impressive enough). But real-world effectiveness, laudable and worthy of celebration though it may be, is a different thing than aesthetic effectiveness, and here's where I'm not quite sure what to do with The Snake Pit.

It's a film torn about the way it wants to approach its material. On the one hand, it is heavily realistic: one of the most realistic productions in Hollywood up to that point, in fact. Director Anatole Litvak, who'd spent World War II contributing to Frank Capra's Why We Fight documentaries for the U.S. military, had some downright revolutionary ideas (by Hollywood standards) for how to strip out the glowing polish of The Movies from his cine-journalism. The most self-evident of these ideas was to reduce or outright eliminate the use of makeup for his nearly all-woman cast, or using makeup to cause de Havilland, to look more wired and gaunt. For that matter, de Havilland also went on a crash diet, to reduce her slender frame and suck even more of the vitality from her face. I have not done the proper research on the matter, but I suspect that de Havilland's performance might be the first time a Hollywood star "de-glammed" to seem more, like, real, man. And in a fine prophecy of what would happen to gorgeous women like Grace Kelly and Charlize Theron, de Havilland nabbed an Oscar nomination for her work (she lost, unfairly, despite being leaps and bounds the stand-out in one of the weakest Best Actress competitions in Academy history - one with Ingrid Bergman, Irene Dunne, and Barbara Stanwyck, no less, all giving some of the worst performances of their careers).

All of which is well and good, but there's a tension running throughout The Snake Pit, where it seems like the people involved in making it hadn't quite figured out what "realism" meant. There's some titanically overbaked nonsense littering the whole film, mostly to do with the depiction of the undifferentiated "sickness" that all of the women onscreen seem to suffer from. It is of course unfair to slag a movie from 1948 for being insufficiently sophisticated about what mental illness looked like, but surely even then, they knew better than this? This screaming, preening, chewing lips and glaring like a terrified deer? At times, it seems like Litvak secretly wishes he was directing a sudsy Susan Hayward dispsomania thriller instead of this very concerned prestige drama, with cinematographer Leo Tover obligingly lighting much of the film like a noir rather than a depiction of allegedly real-world spaces. Litvak also pushes the actors to places that I frankly don't think suit them very well, the leading lady least of all.

Even granting that, de Havilland does as much as she can with what she's given. There are some conceits in Frank Partos and Millen Brand's screenplay, adapted from Mary Jane Ward's celebrated 1946 novel, that are simply beyond redemption: worst among these is the insistence on providing Virginia's interior monologue as she slides from relative lucidity to utter fogginess, and as she tries to hide her weakness from the doctors, while de Havilland pantomimes the feelings she recites to us in voice-over. These moments are ludicrous and terrible. As much as possible, however, the actor tries to synthesise the two strands of the movie into one internally coherent character: treating Virginia's internal confusion with as much gravity as she can, fully inhabiting the all-encompassing sense of fear that the character feels even without knowing, at all points, why she's afraid; at times, that fear bubbles out, and it's here that de Havilland gives into the melodramatic necessities that the film demands, trying as much as possible to suggest that it's the character at a breaking point rather than just the Crazy Lady Going Crazy, which far too much of the screenplay would seem to make the most obvious way to play entire scenes.

It's not to say that de Havilland is waging a single-front war against The Snake Pit sliding into tacky camp. This is more a case of a screenplay making very poor judgments and a director running with them, in the context of a mostly solid depiction of a specific place, rather than an inherently corrupt piece of writing. Some of the most frustrating aspects of the movie aren't even really its fault; the implication that psychoanalysis can cure schizophrenia, a horrifying lesson if ever there was one, really was at the forefront of mental health at the time the movie was made, in the days when Freudian psychoanalysis hadn't lost any of its luster - indeed, was more popular than it had been in Freud's own time. It is unfair to accuse the movie of furthering a cartoonish understanding of how people with mental disorders act and function when it was just about the first movie to treat those disorders as a series topic, and when the cutting edge of science still didn't have a good sense of what the hell was going on inside these people's heads. And if we take The Snake Pit on those terms - a depiction of what mental health treatment in 1948 looked like from the perspective of 1948 - it's a much more tolerable experience, if still tonally dysfuncational.

The "you are there" approach to showcasing the inside of the asylum through one of its patients rather than through the doctors is fruitful for the movie, filling it with a sense of arbitrary, unfair, and frightening stimuli. The shift in mood from the kind (if patronising) treatment of Dr. Kik (Leo Genn) to the barking nastiness of Nurse Davis (Helen Craig) effectively suggests Virginia's sense of being lost and in a whirlwind; the nothing-held-back performances of the supporting cast playing the patients generally work to etch out different kinds of mental imbalance even if the writing doesn't. The face-off between Virginia and a haughty woman played by Beulah Bondi, who fancies herself the wealthiest and most beautiful of women, provides for an exciting acting showcase as de Havilland and Bondi lie to each other in strategic ways, even if it's not terribly insightful as drama.

Anyways, whatever limitations the film has, it's a monumental showcase for de Havilland; it's the performance from her career that impresses me the most, even if it's not the most flawlessly consistent. Coming just a few years into the period after she successfully broke her Warner Bros. contract and became Hollywood's first independent movie star, The Snake Pit is every bit the project that an actor who'd been stalled out in a bunch of delicate flower roles like Melanie in Gone with the Wind does when she wants to prove that she's got plenty of other tricks up her sleeve. If her 1946 Oscar-winning turn in To Each His Own first demonstrated that she could be anything other than a saint (while dragging her performance down with an even more tonally inept screenplay than this one), it's in The Snake Pit that we first see an actively unpleasant de Havilland, as she exudes paranoid mistrust of the people around her, manifesting in sour facial expressions and angry, snappish line deliveries flowing in and out of sweeter modes. Though in this film, even the sweetness feels like a put on, de Havilland suggesting that Virginia is trying to adopt a pleasant purity that she doesn't feel as a defense against confusion and abuse. It's not always clear that the actor has quite traced why her character moves from one mode to the next, but the closer we get to the end, the more precise and coherent her character creation is, drawing moments together into a singular momentum. So perhaps what looks like sloppiness in the early going is really just strategy: de Havilland suggesting Virginia's lack of consistent self-definition so that the contrast when she starts to be able to stick to a single, concrete internal narrative is clearer. It's probably all just in service to a script that hasn't completely cracked the way to depict a mental disorder it plainly doesn't understand, but de Havilland's bravura performance has enough force to push the whole project along even when its script is stuck in a tailspin.