Blockbuster History: Nothing up my sleeve

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: combining two things that go together pretty well, all things considered Now You See Me combines the showy world of magicians with the twisty world of the con artist, These two discrete forms of professional liars have been paired many times throughout cinema history, but the best iteration I have seen takes us as far from glossy summertime fare as it is possible to go.

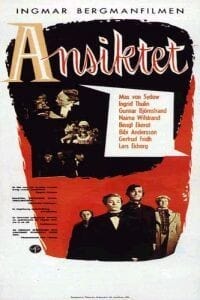

The Magician (a far safer and blander title than the Swedish original, Ansiktet, "The Face") is something of a forgotten Ingmar Bergman film, or at least an overlooked one. Coming out in 1958, just a year after the career-making one-two punch of The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries will do that to a film, preventing it from developing the insta-reputation that accrued to many of the director's A-list films in the '60s and '70s. It's also a weird outlier given the direction the famously dour auteur's career headed in the wake of Wild Strawberries, into searing dramas about unhappy people not believing in God and waiting on their own death: there's a strain of blowsy humor running through the whole picture, and it's bookended by scenes that avowedly traffic in horror film imagery, though it doesn't entirely follow that they can therefore be described as "horror".

It is still, in its way, a movie about the loss of faith, though that theme is explored in a completely different way than the director's celebrated trilogy on that subject beginning with 1961's Through a Glass Darkly, and the faith being shattered isn't even centered around religion (unless it be metaphorically). In fact, the second-tier crisis of faith is suffered by a resolutely irritable man of science who is thrown, at least briefly, by the possibility that there are more things in heaven and earth than dreamt of in his philosophy. But the greater crisis is that undergone by the magician of the English title (and it's probably his face that the Swedish title refers to), Albert Emanuel Vogler (Max von Sydow), a conjurer driven to muteness from some unspecified sense of psychic weariness,* traveling around Europe in the mid-18th Century (near the end of the movie, it's specified to be 1846), touring with his magnetisk hälsoteater, "magnetic health theater", which appears to be something of a hypnotism show. Vogler, which I believe to be the first character to boast that highly significant and frequently repeated Bergman surname (most famously attached to fellow traumatic mute Elisabeth Vogler of Persona), is typically read as being a largely autobiographical figure, in which the film and theater director explores and to some degree apologises for the truth inherent to both of his beloved artforms, which is that they are complete bald-faced lies.

This is something that many artistically inclined filmmakers have confronted throughout the history of the medium, though usually with recourse to the idea that the outrageous fiction of cinema is in service to a greater emotional truth, or just by being playful and frivolous about it. Neither of these approaches apply to The Magician, which is playful and frivolous only by the standard of Bergman's other movies. Taken by itself, there's a great deal of brutality in the way that Vogler's anxiety and depression at the thought that he really is the cheap charlatan his enemies accuse him of being is depicted without being analysed in any cathartic way. None of this, by the way, is spelled out in the script; it's mostly communicated by recourse to close-up shots of von Sydow's face (the title again! Why the hell did the English-language distributors call this The Magician, anyway?) with its look of unmitigated sorrow.

What separates The Magician from many films - particularly those of, say, Jean-Luc Godard, who made a career out of calling attention to the inherent artifice of narrative cinema - is that Bergman isn't remotely interested in exploring the fact of the lies that dramatic art tells, but the impact of those lies on the teller and the viewer. What's most fascinaiting about it is the way that it implicates its own audience, in a roundabout way, by demonstrating that in order to appreciate the art being presented (e.g. Vogler's magic show), the audience has to elect to believe in it. Hence, Vogler's assistant Aman (Ingrid Thulin), plainly a woman from the first frame when we see him/her, but nobody onscreen seems to realise that until somebody walks in on her in a state of undress. Hence an otherwise totally unnecessary narrative parenthesis, where for a solid 20 or 30 minutes smack in the middle of the drama, all of the principals are kept offscreen in favor a random B-plot. Here, we see Vogler's aides Tubal (Åke Fridell) and Simson (Lars Ekborg) flirting with two servants of the town leader, Sara (Bibi Andersson) and Sofia (Sif Ruud), and for a long time it seems absolutely trivial, until the shape begins to emerge of a story in which Simson uses a completely fanciful love potion to seduce Sara, trying to trick her into believing his cock and bull story and not entirely noticing that by playing along with him, she's actually in charge of the situation (Andersson, a Bergman regular, gives possibly the film's most sophisticated and delicate performance, even more impressive because it's situated in broad, bawdy comedy, rather than the more complicated and showy dramatic A-plot). The argument being that if we are to get anything meaningful out of art, be it Vogler's sideshow or Bergman's ascetic investigation of the same, it's because we've agreed to give ourselves up for it: we are playing the slutty maid to the film's horny coachman, and if it is able to use its fiction to move us, that's only because we've agreed to treat the fiction as real for the purposes of getting on with it.

This isn't the only way that film makes this argument: there is, for example, the way that it opens in a tremendously atmospheric, otherworldly place of horror, except is nonsensical and not scary; generically, it has only the value we agree that it has (the later horror sequence near the film's end has a totally different meaning, and I'll get there shortly. Of course, Bergman and the second-best cinematographer he frequently collaborated with, Gunnar Fischer, do such a good job of crafting the haunted glen feeling of the movie's early night sequences that buying into the idea that it's horrifying is fairly easy.

The argument isn't just about appreciating art, though, it's about using knowing fiction as a way to survive life. The primary conflict in The Magician is between the self-doubting liar Vogler and Dr. Vergerus (Gunnar Björnstrand), the local minister of public health who is keenly anxious to prove that Vogler's antics are harmful trickery. Vergerus is also an intense, dedicated atheist, and the film's excellent climax consists of Vogler playing a tremendously convincing trick on him, designed solely to unsettle his certainty that nothing exists which cannot be rationally explained. It's for this reason that the final horror sequence functions so differently than the first: Vergerus is our analogue, for where we stand coolly and intellectually removed from the material, so does he, until the sequence where Bergman/Vogler uses all his skill to thoroughly unnerve Vergerus in a horror scene that is much deeper than the spooky woods of the opening, using deep black underlit images and confounding imagery to make us just as thrown by the sudden shift into the uncanny as the doubting doctor is.

The film ends, mostly, with Vergerus asserting his superiority once again, but we don't quite believe it; The Magician has successfully made its claim that we can know something to be false but still find it effective at moving us, even if we want to pretend otherwise (which the film encourages with its tremendously fake last scene, in which everything ends much too happily and cleanly, though the ironic final shot - or, more particularly, the ironic sound mix accompanying the final shot - makes it clear that the movie doesn't buy it any more than we do). Vogler's art is meaningful because people want to believe in magic; Bergman's art is meaningful because people want to believe in aesthetic transcendence. And, if we place the film within the context of Bergman's deconstruction of religion at this time in his career, belief in the supernatural (a Christian God or otherwise) might be believing a lie, but it's a lie that gives a shape and support to our life. There's an ambivalence that underpins everything in the film: its uncertain switch from genre to genre, its presentation of character as fully-formed personalities who nonetheless frequently lack stable identities (Vogler's obviously fake beard, making him look uncommonly like the Jesus Christ that von Sydow would play seven years later in The Greatest Story Ever Told, is particularly important in this context), its self-consciously artificial plot. And this ambivalence exactly maps onto the religious uncertainty of a post-war society of semi-intellectuals who wanted to believe in a traditional God that they were fairly certain did not exist. For so effectively creating a parable for that development, The Magician can only count as tremendously important Bergman, even it it doesn't have the instant cachet of his more famous and direct movies.

*I just realised, and physically recoiled from my computer as I did so, that this connects this performance to his similarly mute character in Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close.

The Magician (a far safer and blander title than the Swedish original, Ansiktet, "The Face") is something of a forgotten Ingmar Bergman film, or at least an overlooked one. Coming out in 1958, just a year after the career-making one-two punch of The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries will do that to a film, preventing it from developing the insta-reputation that accrued to many of the director's A-list films in the '60s and '70s. It's also a weird outlier given the direction the famously dour auteur's career headed in the wake of Wild Strawberries, into searing dramas about unhappy people not believing in God and waiting on their own death: there's a strain of blowsy humor running through the whole picture, and it's bookended by scenes that avowedly traffic in horror film imagery, though it doesn't entirely follow that they can therefore be described as "horror".

It is still, in its way, a movie about the loss of faith, though that theme is explored in a completely different way than the director's celebrated trilogy on that subject beginning with 1961's Through a Glass Darkly, and the faith being shattered isn't even centered around religion (unless it be metaphorically). In fact, the second-tier crisis of faith is suffered by a resolutely irritable man of science who is thrown, at least briefly, by the possibility that there are more things in heaven and earth than dreamt of in his philosophy. But the greater crisis is that undergone by the magician of the English title (and it's probably his face that the Swedish title refers to), Albert Emanuel Vogler (Max von Sydow), a conjurer driven to muteness from some unspecified sense of psychic weariness,* traveling around Europe in the mid-18th Century (near the end of the movie, it's specified to be 1846), touring with his magnetisk hälsoteater, "magnetic health theater", which appears to be something of a hypnotism show. Vogler, which I believe to be the first character to boast that highly significant and frequently repeated Bergman surname (most famously attached to fellow traumatic mute Elisabeth Vogler of Persona), is typically read as being a largely autobiographical figure, in which the film and theater director explores and to some degree apologises for the truth inherent to both of his beloved artforms, which is that they are complete bald-faced lies.

This is something that many artistically inclined filmmakers have confronted throughout the history of the medium, though usually with recourse to the idea that the outrageous fiction of cinema is in service to a greater emotional truth, or just by being playful and frivolous about it. Neither of these approaches apply to The Magician, which is playful and frivolous only by the standard of Bergman's other movies. Taken by itself, there's a great deal of brutality in the way that Vogler's anxiety and depression at the thought that he really is the cheap charlatan his enemies accuse him of being is depicted without being analysed in any cathartic way. None of this, by the way, is spelled out in the script; it's mostly communicated by recourse to close-up shots of von Sydow's face (the title again! Why the hell did the English-language distributors call this The Magician, anyway?) with its look of unmitigated sorrow.

What separates The Magician from many films - particularly those of, say, Jean-Luc Godard, who made a career out of calling attention to the inherent artifice of narrative cinema - is that Bergman isn't remotely interested in exploring the fact of the lies that dramatic art tells, but the impact of those lies on the teller and the viewer. What's most fascinaiting about it is the way that it implicates its own audience, in a roundabout way, by demonstrating that in order to appreciate the art being presented (e.g. Vogler's magic show), the audience has to elect to believe in it. Hence, Vogler's assistant Aman (Ingrid Thulin), plainly a woman from the first frame when we see him/her, but nobody onscreen seems to realise that until somebody walks in on her in a state of undress. Hence an otherwise totally unnecessary narrative parenthesis, where for a solid 20 or 30 minutes smack in the middle of the drama, all of the principals are kept offscreen in favor a random B-plot. Here, we see Vogler's aides Tubal (Åke Fridell) and Simson (Lars Ekborg) flirting with two servants of the town leader, Sara (Bibi Andersson) and Sofia (Sif Ruud), and for a long time it seems absolutely trivial, until the shape begins to emerge of a story in which Simson uses a completely fanciful love potion to seduce Sara, trying to trick her into believing his cock and bull story and not entirely noticing that by playing along with him, she's actually in charge of the situation (Andersson, a Bergman regular, gives possibly the film's most sophisticated and delicate performance, even more impressive because it's situated in broad, bawdy comedy, rather than the more complicated and showy dramatic A-plot). The argument being that if we are to get anything meaningful out of art, be it Vogler's sideshow or Bergman's ascetic investigation of the same, it's because we've agreed to give ourselves up for it: we are playing the slutty maid to the film's horny coachman, and if it is able to use its fiction to move us, that's only because we've agreed to treat the fiction as real for the purposes of getting on with it.

This isn't the only way that film makes this argument: there is, for example, the way that it opens in a tremendously atmospheric, otherworldly place of horror, except is nonsensical and not scary; generically, it has only the value we agree that it has (the later horror sequence near the film's end has a totally different meaning, and I'll get there shortly. Of course, Bergman and the second-best cinematographer he frequently collaborated with, Gunnar Fischer, do such a good job of crafting the haunted glen feeling of the movie's early night sequences that buying into the idea that it's horrifying is fairly easy.

The argument isn't just about appreciating art, though, it's about using knowing fiction as a way to survive life. The primary conflict in The Magician is between the self-doubting liar Vogler and Dr. Vergerus (Gunnar Björnstrand), the local minister of public health who is keenly anxious to prove that Vogler's antics are harmful trickery. Vergerus is also an intense, dedicated atheist, and the film's excellent climax consists of Vogler playing a tremendously convincing trick on him, designed solely to unsettle his certainty that nothing exists which cannot be rationally explained. It's for this reason that the final horror sequence functions so differently than the first: Vergerus is our analogue, for where we stand coolly and intellectually removed from the material, so does he, until the sequence where Bergman/Vogler uses all his skill to thoroughly unnerve Vergerus in a horror scene that is much deeper than the spooky woods of the opening, using deep black underlit images and confounding imagery to make us just as thrown by the sudden shift into the uncanny as the doubting doctor is.

The film ends, mostly, with Vergerus asserting his superiority once again, but we don't quite believe it; The Magician has successfully made its claim that we can know something to be false but still find it effective at moving us, even if we want to pretend otherwise (which the film encourages with its tremendously fake last scene, in which everything ends much too happily and cleanly, though the ironic final shot - or, more particularly, the ironic sound mix accompanying the final shot - makes it clear that the movie doesn't buy it any more than we do). Vogler's art is meaningful because people want to believe in magic; Bergman's art is meaningful because people want to believe in aesthetic transcendence. And, if we place the film within the context of Bergman's deconstruction of religion at this time in his career, belief in the supernatural (a Christian God or otherwise) might be believing a lie, but it's a lie that gives a shape and support to our life. There's an ambivalence that underpins everything in the film: its uncertain switch from genre to genre, its presentation of character as fully-formed personalities who nonetheless frequently lack stable identities (Vogler's obviously fake beard, making him look uncommonly like the Jesus Christ that von Sydow would play seven years later in The Greatest Story Ever Told, is particularly important in this context), its self-consciously artificial plot. And this ambivalence exactly maps onto the religious uncertainty of a post-war society of semi-intellectuals who wanted to believe in a traditional God that they were fairly certain did not exist. For so effectively creating a parable for that development, The Magician can only count as tremendously important Bergman, even it it doesn't have the instant cachet of his more famous and direct movies.

*I just realised, and physically recoiled from my computer as I did so, that this connects this performance to his similarly mute character in Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close.