Blockbuster History: Roald Dahl on film

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: Disney and Steven Spielberg combine forces to make The BFG, based upon a novel by a children's novelist with a great deal less sentiment than either of those entities. Roald Dahl's books have served as the fodder for quite a few movies over the years; I would like to invite you to join me in revisiting one of the very first.

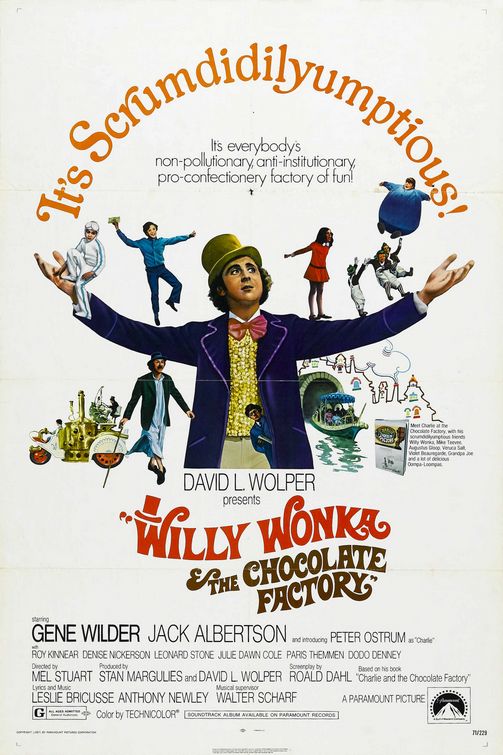

It's no shock when an author complains that the film adaptation of one of his books is a terrible travesty that misses everything important about the original. What is a bit of a shock is for the author in question to make those complaints when he, himself, is the only credited screenwriter for the adaptation, as happened when English misanthrope Roald Dahl was famously disgusted by Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, the 1971 film made out of his classic dark comic children's novella Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. The explanation for how this unique situation came about is easy enough to explain: Dahl might have been the only credited screenwriter, but a substantial amount of revision was applied to his draft by the uncredited David Seltzer, and these include rather significant changes. We might then further ask the question, are these changes truly for the worst, or was Dahl just being a crybaby? And to that, I can firmly declare the answer to be: um, both.

In point of fact, the worst of the changes doesn't merely harm Willy Wonka as an adaptation: it is a self-evidently bad decision solely in reference to the film itself. But we'll get to that point later. For right now, let's quickly catch-up all those readers who were not children in the late 1970s, the 1980s, or the early 1990s, and this were not around to appreciate this classic of family cinema when it was at the height of its reputation, following a financially disappointing theatrical release. Somewhere in a mixture of Germany, Switzerland, and England, there is a small town whose most notable fixture is a mysterious chocolate factory operated by the reclusive Willy Wonka (Gene Wilder). Its products are renowned the world over, and Wonka's operation is the focus of all the most vigorous candy industry espionage.

In the same town, there lives a desperately poor family, consisting of four bedridden senior citizens, a middle-aged single mother (Diana Swole), and her sorrowful preteen son named Charlie Bucket (Peter Ostrum). Charlie's one dream is to have the disposable income to be able to eat candy to his heart's content, instead of the cabbage water and - oh so rarely, a loaf of bread - that makes up the family's sustenance. The first ray of hope that enters Charlie's deprived world comes when Wonka announces a contest: five Wonka products, somewhere in the world, have been wrapped with golden tickets inside, and the recipients of those tickets will be the first people in years to see inside the mysterious Wonka factory on a tour led by Wonka himself, in addition to receiving a lifetime supply of chocolate. Eventually, Charlie manages to acquire one such ticket, and joins four other children, all repulsive in some way or another, on an incident-filled trip through the fantastic spaces inside the factory, all of which cause the naughty children to experience some ironic fate that nearly kills them. And the elfin Wonka seems to be incredibly pleased by all of this.

If nothing else, the material of this story points out the razor-thin line between horror and comedy in children's literature. That, of course, was the thing Dahl did best: his books, even the very fluffiest and friendliest (and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is neither), are profoundly dark and nasty-minded, punishing the guilty (often in immense disproportion to their crimes) and providing vivid wish-fulfillment for children who are quietly convinced that they are the best, smartest, most deserving young person alive - which is to say, all children who have ever lived. Dahl famously hated children, which is surely the reason his books for them have survived: if you regard kids as a bunch of bastards, you're not likely to talk down to them, and if you suss out that kids secretly all have an abiding cruel streak and love of outrageous morbidity, you will indulge it. That Dahl had an exceptional sense of sarcastic wit, an enviable facility with the sounds of the English language that permitted him to create invented names and words like nobody this side of Charles Dickens, and a tremendously visual sense of prose are all just added bonuses.

Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory isn't really a perfect embodiment of any of that, but as a first attempt at adapting Dahl's children's fiction to the screen (some of his spy fiction had been filmed, primarily on television), it's a good stab at it. There's only one unabashed "hell yes, this is Dahl" moment in the film - Charlie meeting a tinker (Peter Capell) with knives hanging off of his cart, who intones grim thoughts outside of the locked Wonka gate - but the sense terribly self-amused cruelty is never terribly far away, particularly once Wilder finally shows up, close to the half-way point of the movie.

But anyway, the value of a thing is not, inherently, the same as its fidelity as a work of adaptation. On its own terms, Willy Wonka is a mostly charming, at times dreadfully irritating thing, and I apologise to everyone for whom this is an unlimited childhood classic. I watched it a lot myself, as a young person; parts of annoyed me even then. It's the songs, more than anything: producer David Wolper concluded somewhere along the line that all the big kids' classics were musicals, and so his film would damn well be the same thing, a decision that even the film's director, Mel Stuart, had to be talked into (allegedly; there are a lot of cute making-of stories surrounding Willy Wonka, and I can't believe every last one of them is the sober gospel truth). The songs were written by the team of Leslie Bricusse and Anthony Newley, still in the glow of their big '60s stage hits Stop the World - I Want to Get Off and The Roar of the Greasepaint - The Smell of the Crowd, though the sepulchral 1967 film Doctor Dolittle (with songs by Bricusse, and Newley in a major role) had perhaps knocked some of the gleam off. At any rate, they provided six original songs for the soundtrack, and not one of them is terrifically good, though at least "The Candy Man" has endured as a standard. I am sure plenty of people would disagree with me in a flush of outraged horror. At any rate, I find the lyrics in the best songs - "The Candy Man" and "Pure Imagination" - to be rather smugly overdetermined, with anxiety-inducing forced rhymes. And the ostensibly sweet, heart-melting ballad "Cheer Up Charlie" has been leaving me peevish since I was six years old, grinding the plot to a halt to drop a steaming slice of '70s singer-songwriter cheese onto a character who serves very little other purpose than the sing this song.

Anyways, if the songs were cut out, it would brighten Willy Wonka's pace and comic energy considerably (though I would regret losing the haunting way Wilder sings "Pure Imagination"), for outside of how gummy those moments are, it's a pretty terrific movie, for the most part. Certainly, no film which began life as a marketing opportunity for silent partner Quaker Oats, looking to get into producing chocolate under the "Wonka" brand name, and insisting on the title change to further that end, ought to be as spry and frequently beautiful as this. Probably the first truly noteworthy thing about the movie is its baffling sense of place: the setting of the film is a timeless, dream version of Europe (it was primarily shot in Munich), heavily British but clearly not of Great Britain. This helps smooth the path for the film's satiric treatment of media culture (which feels, in honesty, more in line with the 1950s than the time of the film's production and release), as a curious, buffoonish intrusion into the placid, ethereal setting of everything else. And this is something that really shouldn't work at all, yet there's something about the contrast between the news and the hushed city that receives it which makes the whole thing feel more special, although it's also the element that most unmistakably dates the film.

What everyone remembers, of course, are the fanciful sets Harper Goff designed for the inside of Wonka's factory: a mixture of pure fantasy, modernist graphic art, industrial chic, and good old-fashioned movie magic. None of it is as marvelous as I thought it was a child - there are some barbarically cheap sets inside that factory - but it does a good job of evoking the kind of fairy tale setting that an impoverished boy like Charlie might dream up. And the wide range of reference points adds considerably to our feeling of a place appeallingly out of step with the world. At its best moments, Willy Wonka evokes the spirit, if not the letter of an Alice in Wonderland setting where geometry and perspective are conditional or nonexistent, and where a light surrealism coats everything.

The setting and visuals are, generally speaking, stronger than the rest of the movie; there's a real charm to it, but it's all a bit less... less, than it should be. Stuart's directing lacks the twinkle in the eye of Dahl's prose, which is why a great deal of what feels like it should push the film towards a dry English absurdism, like the 20-years-bedridden grandparents, is simply swallowed up into the background. It is a cute movie, when it maybe ought to be a funny movie. But cute counts for something, and the interplay between Ostrum and Jack Albertson, playing the most lively of the grandparents, Joe, drives the first half of the movie well enough that the absence of wit or even much sustained whimsy doesn't hurt it very much.

The second half of the movie is a completely different matter; and it's a bit surprising, revisiting the thing, how very different the two halves are. After serving as the protagonist and recipient of a very clear, strong character arc in the first half, Charlie almost disappears, as the movie prefers instead to focus on the four very naughty children accompanying him on the tour, all of whom it regards as more amusing in their wickedness than is the case (in particular, the greedy Veruca Salt, played by Julie Dawn Cole - the only one of the child actors here to pursue much of a career - is pure agony; and she's supposed to be, but "successful at being hatefully annoying" is a dubious kind of success). Even more than them, it starts to fixate on Wonka, and why wouldn't it? Gene Wilder's performance is the absolute triumph of Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, and the difference between "an unbalanced curiosity with great sets and locations" and "an abiding classic of children's cinema" is entirely his presence. Above everything else, Wilder manages to make Wonka feel subtly but decisively inhuman: the way he speaks to the other characters, his body language, and above all his tone of voice, suggest in a very clear way a being on some other plane of consciousness - not a higher plane, but a very different one. It would be easy to take the script and conclude that Wonka is just joyfully callous and sardonic, and that could still have worked, by Wilder plays the role as something like Santa Claus crossed with Loki, and I adore every bit of it: the unfocused look in his eyes, staring through things and not at them (which adds a minute but potent sense of melancholy to the character, which is only clarified in the last scenes); the elfin movement down the stairs in the big chocolate river room; the way he tunelessly sings the literary references Seltzer seeded into the script. The actor had the good sense to know that he had to make Wonka essentially unpredictable and unknowable in order to generate the sense of otherworldly magic that the second half of the film thrives on, and there's not one single beat of the performance where that doesn't come through.

The script undoubtedly becomes a muddle at this point, lacking the ironic moralising of the book (whose sharpest edges it always chooses to sand down), and dropping all of the emotional momentum of the first half until the somewhat peremptory final scene. But Wilder's such a magnetic presence that he largely makes it work. Largely. We still have to deal with the completely impossible matter of the one truly awful addition to the script, one of two deal-breakers for Dahl (he was equally offended by the creation of a secretive conspiratorial villain, but taken on its own terms, I think the film makes it work). The four nasty children all break the rules and are punished; this is well and good, in keeping with the Grimm sensibility Dahl used to fuel his comedy. In the movie, however, Charlie and Grandpa Joe also break the rules, and this is unbelievably wrong and bad. The whole damn point is that Charlie has a moral compass and good sense. He is the only one of the five children who hasn't decided to betray Wonka's secrets, and the only one who found his golden ticket after buying a chocolate bar for the love of chocolate (and also for another person), rather than out of greed. He's the sickly-sweet pure innocent; but this is a goddamn fable. It needs an exaggerated innocent. And along comes the Fizzy Lifting Drink scene to fuck that up completely. It adds nothing other than burp jokes and heinously bad dubbing, at the cost of elegance.

It's the only outright bum note in a screenplay that, even at its muddiest, has a sense of playfulness and arch humor that work well and give Wilder, if not really anybody else in the cast, plenty to do. There's little doubt in my mind that the film has a rosier reputation than it earns, but its strengths are awfully good, and Wilder is one for the history books. Dahl would be better-served by the movies, multiple times; but even if it's a weak approximation of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Willy Wonka has enough going for it that I can't really quibble with the adoration it's racked up over the years.

It's no shock when an author complains that the film adaptation of one of his books is a terrible travesty that misses everything important about the original. What is a bit of a shock is for the author in question to make those complaints when he, himself, is the only credited screenwriter for the adaptation, as happened when English misanthrope Roald Dahl was famously disgusted by Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, the 1971 film made out of his classic dark comic children's novella Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. The explanation for how this unique situation came about is easy enough to explain: Dahl might have been the only credited screenwriter, but a substantial amount of revision was applied to his draft by the uncredited David Seltzer, and these include rather significant changes. We might then further ask the question, are these changes truly for the worst, or was Dahl just being a crybaby? And to that, I can firmly declare the answer to be: um, both.

In point of fact, the worst of the changes doesn't merely harm Willy Wonka as an adaptation: it is a self-evidently bad decision solely in reference to the film itself. But we'll get to that point later. For right now, let's quickly catch-up all those readers who were not children in the late 1970s, the 1980s, or the early 1990s, and this were not around to appreciate this classic of family cinema when it was at the height of its reputation, following a financially disappointing theatrical release. Somewhere in a mixture of Germany, Switzerland, and England, there is a small town whose most notable fixture is a mysterious chocolate factory operated by the reclusive Willy Wonka (Gene Wilder). Its products are renowned the world over, and Wonka's operation is the focus of all the most vigorous candy industry espionage.

In the same town, there lives a desperately poor family, consisting of four bedridden senior citizens, a middle-aged single mother (Diana Swole), and her sorrowful preteen son named Charlie Bucket (Peter Ostrum). Charlie's one dream is to have the disposable income to be able to eat candy to his heart's content, instead of the cabbage water and - oh so rarely, a loaf of bread - that makes up the family's sustenance. The first ray of hope that enters Charlie's deprived world comes when Wonka announces a contest: five Wonka products, somewhere in the world, have been wrapped with golden tickets inside, and the recipients of those tickets will be the first people in years to see inside the mysterious Wonka factory on a tour led by Wonka himself, in addition to receiving a lifetime supply of chocolate. Eventually, Charlie manages to acquire one such ticket, and joins four other children, all repulsive in some way or another, on an incident-filled trip through the fantastic spaces inside the factory, all of which cause the naughty children to experience some ironic fate that nearly kills them. And the elfin Wonka seems to be incredibly pleased by all of this.

If nothing else, the material of this story points out the razor-thin line between horror and comedy in children's literature. That, of course, was the thing Dahl did best: his books, even the very fluffiest and friendliest (and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is neither), are profoundly dark and nasty-minded, punishing the guilty (often in immense disproportion to their crimes) and providing vivid wish-fulfillment for children who are quietly convinced that they are the best, smartest, most deserving young person alive - which is to say, all children who have ever lived. Dahl famously hated children, which is surely the reason his books for them have survived: if you regard kids as a bunch of bastards, you're not likely to talk down to them, and if you suss out that kids secretly all have an abiding cruel streak and love of outrageous morbidity, you will indulge it. That Dahl had an exceptional sense of sarcastic wit, an enviable facility with the sounds of the English language that permitted him to create invented names and words like nobody this side of Charles Dickens, and a tremendously visual sense of prose are all just added bonuses.

Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory isn't really a perfect embodiment of any of that, but as a first attempt at adapting Dahl's children's fiction to the screen (some of his spy fiction had been filmed, primarily on television), it's a good stab at it. There's only one unabashed "hell yes, this is Dahl" moment in the film - Charlie meeting a tinker (Peter Capell) with knives hanging off of his cart, who intones grim thoughts outside of the locked Wonka gate - but the sense terribly self-amused cruelty is never terribly far away, particularly once Wilder finally shows up, close to the half-way point of the movie.

But anyway, the value of a thing is not, inherently, the same as its fidelity as a work of adaptation. On its own terms, Willy Wonka is a mostly charming, at times dreadfully irritating thing, and I apologise to everyone for whom this is an unlimited childhood classic. I watched it a lot myself, as a young person; parts of annoyed me even then. It's the songs, more than anything: producer David Wolper concluded somewhere along the line that all the big kids' classics were musicals, and so his film would damn well be the same thing, a decision that even the film's director, Mel Stuart, had to be talked into (allegedly; there are a lot of cute making-of stories surrounding Willy Wonka, and I can't believe every last one of them is the sober gospel truth). The songs were written by the team of Leslie Bricusse and Anthony Newley, still in the glow of their big '60s stage hits Stop the World - I Want to Get Off and The Roar of the Greasepaint - The Smell of the Crowd, though the sepulchral 1967 film Doctor Dolittle (with songs by Bricusse, and Newley in a major role) had perhaps knocked some of the gleam off. At any rate, they provided six original songs for the soundtrack, and not one of them is terrifically good, though at least "The Candy Man" has endured as a standard. I am sure plenty of people would disagree with me in a flush of outraged horror. At any rate, I find the lyrics in the best songs - "The Candy Man" and "Pure Imagination" - to be rather smugly overdetermined, with anxiety-inducing forced rhymes. And the ostensibly sweet, heart-melting ballad "Cheer Up Charlie" has been leaving me peevish since I was six years old, grinding the plot to a halt to drop a steaming slice of '70s singer-songwriter cheese onto a character who serves very little other purpose than the sing this song.

Anyways, if the songs were cut out, it would brighten Willy Wonka's pace and comic energy considerably (though I would regret losing the haunting way Wilder sings "Pure Imagination"), for outside of how gummy those moments are, it's a pretty terrific movie, for the most part. Certainly, no film which began life as a marketing opportunity for silent partner Quaker Oats, looking to get into producing chocolate under the "Wonka" brand name, and insisting on the title change to further that end, ought to be as spry and frequently beautiful as this. Probably the first truly noteworthy thing about the movie is its baffling sense of place: the setting of the film is a timeless, dream version of Europe (it was primarily shot in Munich), heavily British but clearly not of Great Britain. This helps smooth the path for the film's satiric treatment of media culture (which feels, in honesty, more in line with the 1950s than the time of the film's production and release), as a curious, buffoonish intrusion into the placid, ethereal setting of everything else. And this is something that really shouldn't work at all, yet there's something about the contrast between the news and the hushed city that receives it which makes the whole thing feel more special, although it's also the element that most unmistakably dates the film.

What everyone remembers, of course, are the fanciful sets Harper Goff designed for the inside of Wonka's factory: a mixture of pure fantasy, modernist graphic art, industrial chic, and good old-fashioned movie magic. None of it is as marvelous as I thought it was a child - there are some barbarically cheap sets inside that factory - but it does a good job of evoking the kind of fairy tale setting that an impoverished boy like Charlie might dream up. And the wide range of reference points adds considerably to our feeling of a place appeallingly out of step with the world. At its best moments, Willy Wonka evokes the spirit, if not the letter of an Alice in Wonderland setting where geometry and perspective are conditional or nonexistent, and where a light surrealism coats everything.

The setting and visuals are, generally speaking, stronger than the rest of the movie; there's a real charm to it, but it's all a bit less... less, than it should be. Stuart's directing lacks the twinkle in the eye of Dahl's prose, which is why a great deal of what feels like it should push the film towards a dry English absurdism, like the 20-years-bedridden grandparents, is simply swallowed up into the background. It is a cute movie, when it maybe ought to be a funny movie. But cute counts for something, and the interplay between Ostrum and Jack Albertson, playing the most lively of the grandparents, Joe, drives the first half of the movie well enough that the absence of wit or even much sustained whimsy doesn't hurt it very much.

The second half of the movie is a completely different matter; and it's a bit surprising, revisiting the thing, how very different the two halves are. After serving as the protagonist and recipient of a very clear, strong character arc in the first half, Charlie almost disappears, as the movie prefers instead to focus on the four very naughty children accompanying him on the tour, all of whom it regards as more amusing in their wickedness than is the case (in particular, the greedy Veruca Salt, played by Julie Dawn Cole - the only one of the child actors here to pursue much of a career - is pure agony; and she's supposed to be, but "successful at being hatefully annoying" is a dubious kind of success). Even more than them, it starts to fixate on Wonka, and why wouldn't it? Gene Wilder's performance is the absolute triumph of Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, and the difference between "an unbalanced curiosity with great sets and locations" and "an abiding classic of children's cinema" is entirely his presence. Above everything else, Wilder manages to make Wonka feel subtly but decisively inhuman: the way he speaks to the other characters, his body language, and above all his tone of voice, suggest in a very clear way a being on some other plane of consciousness - not a higher plane, but a very different one. It would be easy to take the script and conclude that Wonka is just joyfully callous and sardonic, and that could still have worked, by Wilder plays the role as something like Santa Claus crossed with Loki, and I adore every bit of it: the unfocused look in his eyes, staring through things and not at them (which adds a minute but potent sense of melancholy to the character, which is only clarified in the last scenes); the elfin movement down the stairs in the big chocolate river room; the way he tunelessly sings the literary references Seltzer seeded into the script. The actor had the good sense to know that he had to make Wonka essentially unpredictable and unknowable in order to generate the sense of otherworldly magic that the second half of the film thrives on, and there's not one single beat of the performance where that doesn't come through.

The script undoubtedly becomes a muddle at this point, lacking the ironic moralising of the book (whose sharpest edges it always chooses to sand down), and dropping all of the emotional momentum of the first half until the somewhat peremptory final scene. But Wilder's such a magnetic presence that he largely makes it work. Largely. We still have to deal with the completely impossible matter of the one truly awful addition to the script, one of two deal-breakers for Dahl (he was equally offended by the creation of a secretive conspiratorial villain, but taken on its own terms, I think the film makes it work). The four nasty children all break the rules and are punished; this is well and good, in keeping with the Grimm sensibility Dahl used to fuel his comedy. In the movie, however, Charlie and Grandpa Joe also break the rules, and this is unbelievably wrong and bad. The whole damn point is that Charlie has a moral compass and good sense. He is the only one of the five children who hasn't decided to betray Wonka's secrets, and the only one who found his golden ticket after buying a chocolate bar for the love of chocolate (and also for another person), rather than out of greed. He's the sickly-sweet pure innocent; but this is a goddamn fable. It needs an exaggerated innocent. And along comes the Fizzy Lifting Drink scene to fuck that up completely. It adds nothing other than burp jokes and heinously bad dubbing, at the cost of elegance.

It's the only outright bum note in a screenplay that, even at its muddiest, has a sense of playfulness and arch humor that work well and give Wilder, if not really anybody else in the cast, plenty to do. There's little doubt in my mind that the film has a rosier reputation than it earns, but its strengths are awfully good, and Wilder is one for the history books. Dahl would be better-served by the movies, multiple times; but even if it's a weak approximation of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Willy Wonka has enough going for it that I can't really quibble with the adoration it's racked up over the years.