Summer of Blood: The toolbox murderer

I didn't build my Canadian Summer of Blood schedule along regional lines - an oversight that I now regret - so any evidence I have is strictly anecdotal, but it's beginning to seem to me that, despite the rich history of Canadian horror cinema, those French-Canadians didn't really get into it very much. Indeed, following Visiting Hours, our present subject is only the second shot-in-Québec film we've hit this summer, and I regret to say, the last. Moreover, it's in English - I can't even find a French-language Canadian horror film made prior to the 2000s* - so "French-Canadian" is a bit of a misnomer, even it does boast a French-speaking producer in Pierre Grise (not Jack Bravman, as the IMDb and many reviews claim; he is merely the film's "presenter").

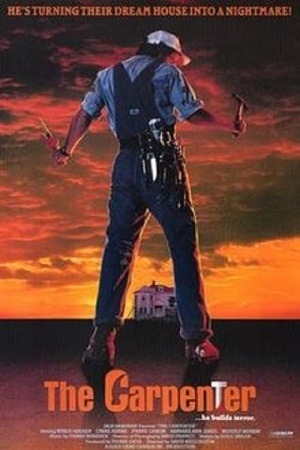

We must not permit 1988's The Carpenter to stand in for Québecois horror as a body, though, for here is the one important thing about The Carpenter, transcending any and all other concerns: it is a peculiar movie. Damn peculiar, I might even go so far as to say. And I use "peculiar" very deliberately and purposefully, for while I have contented myself that it certainly earns that adjective and no obective viewer could ever dare to deny it, I have not and cannot decide if that peculiarity makes the film "good" or "bad"; I do not suppose that even a lifetime of study and consideration will ever entirely resolve that question in my mind. That's assuming, of course, that I dedicate a lifetime of study to The Carpenter, and if anything I ever say implies that I'm doing so, I hope that every single one of my readers will turn on me like a pack of wolves.

For starters, let's just pin down what the thing is. There's a woman, Alice Jarett (Lynne Adams), who decides one afternoon to cut all of her husband's suits apart with a pair of scissors. When Martin Jarette (Pierre Lenoir) comes home from a long day of teaching college literature classes - why he has a separate last name, I cannot say, but it's clear as day in the end credits, and these are credits that also refer to the "sound mixiny" studio, so they're surely to be trusted - he responds with a deapan quip, and just like that, pitches his wife in the loony bin.

No, seriously: the very next cut after his jape is to the room where his wife has been monitored for some while, apparently, given the way the Jarettsettes get to talking. This leads right off into a dissolve-driven montage of events from Alice's stay, along with Martin's purchase of an old house out in the country to serve as his wife's place of convalescence, knowing that he release from the psycho ward will come any day. That day is the very morning after a nightmare she has where her doctor (Griffith Brewer) cuts her from her hospital bed with a chainsaw, and in the morning, the real-life version of that man is even more deranged, wishing her well with a hearty "You have to be crazy to come back to a place like this!", upon which he starts laughing huge, physically heaving laughs, like he'd just told the equivalent of every Grouch Marx joke in recorded history at the same time.

I could go on like this, I promise. The Carpenter is one lunacy after another, for 87 minutes (in the uncut version marginally released to DVD, at least), and reader, know this: I have never taken so many notes while watching any movie in my entire history of reviewing movies. Every damn thing that happened was such a precious gem of surrealism that I wanted to make certain that I pinned it down, like an iridescent butterfly of some previously unknown species. But I will not trouble you with a plot synopsis at that level of detail.

Suffice it to say that the home that Martin bought for his wife was left incomplete, so he's contracted a crew under the management of a man named Farnsworth (Wings Hauser, one of the more iconic Bad Movie Character Actors of the '80s) to patch it up, while the couple is living there. One night, the still-very-delicate Alice wakes up - or dreams? - to the sound of hammering in the basement, and she finds Farnsworth there, working late into the night, shooting rats with a nail gun as he goes. In the morning, this late-night carpentry is found by the rest of the crew, who believe that it must be the work of scabs, proving - or does it? - that Farnsworth was really in the house - or was he?

To make a long story a bit less long than it could be, Martin is screwing around with one of his students, Laura Bell (Louise-Marie Mennier) and acting like the most colossal imaginable prick with his wife; hoping to find some measure of solace and convince herself that she can still function, even post-breakdown, Alice gets a job at Mort's Empire of Paint, acing the interview when Mort (Richard Jutras), a twitchy, bespectacled man, asks if she has a history of health problems. "I recently recovered from a nervous breakdown that had me in the hospital for several weeks, and sometimes I see things that can't really be happening, but I know that, so I don't think it's really anything that'll interfere with my job", she responds in the level, professional tones of somebody navigating that tedious "how do you resolve conflict" question. She is hired on the spot.

Man, I'm doing the worst job of keeping this short. But Christ, this movie! It's so addictive to think and discuss all the weird, weird shit that goes down. Alright, so Farnsworth, the carpenter, gets a little bit free and easy with killing crew members who don't cut it - one of them making rapey gestures towards Alice - and the carpenter and the lady start to fall in love with each other, even though it's pretty unmissably obvious to her and us that he's the... ghost? reincarnation? of Edward Ferd, the original builder of the Jarrets' new house, who started killing the repo men that came to take it over as he fussed on it so long that he ended up running out of money to construct it. Alice's sister Rachel (Barbara Ann Jones) shows up to add emotional support when the situation with Martin turns completely unlivable, and- but I could never dream of spoiling things! Save to say that the final line is a magnificent gleaming cherry on a towering sundae of ass-backwards storytelling, desperate stabs at thematic complexity, and deficient filmmaking.

I don't even know where to start with this. The low-hanging fruit is probably the gender argument: it's pretty clear that The Carpenter would like to be taken as a feminist statement (or at least, as a challenge to patriarchal authority), though it's equally clear that it has virtually no idea how to go about this. Heavy-handedness involving Martin's unbridled, and psychologically unlikely vileness, to begin with, including some really leering symbolism at the start when he lectures on Paul Bunyan as a symbol of North American masculinity at its most robust and exaggerated, only to be felled by technology, much like the technological advances that Martin and Edward Ferd themselves are... felled... actually, for all that this scene practically bruises your ribs, it's poking you so hard as it whispers "you get it, right? Martin is Paul Bunyan! Did you get that?", it's not really foreshadowing a goddamn thing, other than that symbols of the patriarchy abound in The Carpenter, and we're not meant to like them. As for the women who take their place, it's not entirely clear to me what kind of systematic ideology they stand in for; the film passes the Bechdel Test, anyway, though barely. And while Alice does emerge as the closest thing the movie has to a strong character, most of her personality is defined in terms of the husband she kind of hates or the sexy spectral carpenter she's falling for.

But that's not really touching much of anything. The meat of the film lies in its intensely bizarre thematic u-turns, and a style so overweening and ineffective that I must pull out a word that I do not like to use at all, "pretentious": and even then, I mean it only in a very narrow definition, which is that the film wants very much to be more than it can possibly manage to be on the budget and talent involved. Director David Wellington frequently indulges in visual schemes that are flat-out insane for a movie of this sort: flowing, grandiose pans and tracking shots that feel like they were made by somebody who has spent so much time studying the camerawork in Jean Renoir films that they have entirely forgotten why Renoir did what he did, and dissolves in place that dissolves are patently not called for: the whole thing is so baldly trying to be "artistic", without actually understanding artistry, that it's a little bit excruciating to watch, what with the film plodding along rather than building momentum. There's a stateliness and ponderous gravity to the visuals that neither the story nor the characters earn in the least.

Especially given how very silly this all is. Frankly, having watched it all the way through, I do not know if The Carpenter is secretly trying to be an absurdist comedy. There's a whole lot of evidence to that effect, of which I've already named some (the over-the-top caricature pretending to be a medical doctor), and even the overwrought camera directing can be though of as parody, if that's really what you want it to be. But there's so much else! I have pages of notes about things that could very seriously be looked on as self-mockery, like the scene where the carpenter, every time the shot-reverse shot sequence cuts back to him, is in the middle of a completely different task: cutting a board, hammering a nail, splitting a brick, cutting drywall, and planing a door, all in the span of 30 seconds. To the non-carpentry-inclined, it would be like showing a chef throwing dry pasta into boiling water, rolling out pie dough, shucking peas, and trimming fat off a steak all in quick succession. Or the obviously tongue-in-cheek death scenes, particularly the charmingly genteel conversation Ed and Alice have as he busily drills holes in a corpse. Or the nightmare where Alice witnesses Ed's penis replaced by a drill (which, tragically, is not shown onscreen). Or the conversation where Martin has small talk with Laura on the phone, trying not to raise Alice's suspicions, resulting in an indescribably arid minute or more of "ums" and "tell me more about thats".

It helps that Wings Hauser gives such a flighty, frivolously cheery performance, like a big overgrown gung-ho boy scout and handyman, that even as he absolutely dominates every single one of his scenes, he also strips of them of even the tiniest measure of serious impact. On the flipside, everybody else in the cast (except for Adams, arguably, doing the best she can with a part plagued by unusually stupid dialogue and unlikely motivations) is giving conventionally terrible performances, and if Hauser was at the heightened level he reaches through some deliberate scheme, surely anything else in the movie would be at that level with him? Besides, even if The Carpenter could be conclusively proven to be an immaculately straitlaced comedy, I still don't know if it would be funny, or what purpose it was all getting to.

No, better just to call it what it looks like; an exceptionally badly-made movie that's so damn loopy and weird that it's fun regardless of anything else. There's not much more you can demand of a late-80s pseudo-slasher (the paranormal and psychological aspects, as well as the '70s-style failing marriage framework, disguise what's ultimately a rather conventional psycho killer plot) than that it be fun; virtually none of them are, and even if The Carpenter comes by that accidentally and ironically, at least it's a crazy, thoroughly engaging piece of nuttery. There's energy to spare a dozen times over, and that alone makes it worthy of note in its genre, and its time.

Body Count: 6, plus a nail-gunned rat; not a huge total for the era, but for the film's relative domesticity, not bad.

We must not permit 1988's The Carpenter to stand in for Québecois horror as a body, though, for here is the one important thing about The Carpenter, transcending any and all other concerns: it is a peculiar movie. Damn peculiar, I might even go so far as to say. And I use "peculiar" very deliberately and purposefully, for while I have contented myself that it certainly earns that adjective and no obective viewer could ever dare to deny it, I have not and cannot decide if that peculiarity makes the film "good" or "bad"; I do not suppose that even a lifetime of study and consideration will ever entirely resolve that question in my mind. That's assuming, of course, that I dedicate a lifetime of study to The Carpenter, and if anything I ever say implies that I'm doing so, I hope that every single one of my readers will turn on me like a pack of wolves.

For starters, let's just pin down what the thing is. There's a woman, Alice Jarett (Lynne Adams), who decides one afternoon to cut all of her husband's suits apart with a pair of scissors. When Martin Jarette (Pierre Lenoir) comes home from a long day of teaching college literature classes - why he has a separate last name, I cannot say, but it's clear as day in the end credits, and these are credits that also refer to the "sound mixiny" studio, so they're surely to be trusted - he responds with a deapan quip, and just like that, pitches his wife in the loony bin.

No, seriously: the very next cut after his jape is to the room where his wife has been monitored for some while, apparently, given the way the Jarettsettes get to talking. This leads right off into a dissolve-driven montage of events from Alice's stay, along with Martin's purchase of an old house out in the country to serve as his wife's place of convalescence, knowing that he release from the psycho ward will come any day. That day is the very morning after a nightmare she has where her doctor (Griffith Brewer) cuts her from her hospital bed with a chainsaw, and in the morning, the real-life version of that man is even more deranged, wishing her well with a hearty "You have to be crazy to come back to a place like this!", upon which he starts laughing huge, physically heaving laughs, like he'd just told the equivalent of every Grouch Marx joke in recorded history at the same time.

I could go on like this, I promise. The Carpenter is one lunacy after another, for 87 minutes (in the uncut version marginally released to DVD, at least), and reader, know this: I have never taken so many notes while watching any movie in my entire history of reviewing movies. Every damn thing that happened was such a precious gem of surrealism that I wanted to make certain that I pinned it down, like an iridescent butterfly of some previously unknown species. But I will not trouble you with a plot synopsis at that level of detail.

Suffice it to say that the home that Martin bought for his wife was left incomplete, so he's contracted a crew under the management of a man named Farnsworth (Wings Hauser, one of the more iconic Bad Movie Character Actors of the '80s) to patch it up, while the couple is living there. One night, the still-very-delicate Alice wakes up - or dreams? - to the sound of hammering in the basement, and she finds Farnsworth there, working late into the night, shooting rats with a nail gun as he goes. In the morning, this late-night carpentry is found by the rest of the crew, who believe that it must be the work of scabs, proving - or does it? - that Farnsworth was really in the house - or was he?

To make a long story a bit less long than it could be, Martin is screwing around with one of his students, Laura Bell (Louise-Marie Mennier) and acting like the most colossal imaginable prick with his wife; hoping to find some measure of solace and convince herself that she can still function, even post-breakdown, Alice gets a job at Mort's Empire of Paint, acing the interview when Mort (Richard Jutras), a twitchy, bespectacled man, asks if she has a history of health problems. "I recently recovered from a nervous breakdown that had me in the hospital for several weeks, and sometimes I see things that can't really be happening, but I know that, so I don't think it's really anything that'll interfere with my job", she responds in the level, professional tones of somebody navigating that tedious "how do you resolve conflict" question. She is hired on the spot.

Man, I'm doing the worst job of keeping this short. But Christ, this movie! It's so addictive to think and discuss all the weird, weird shit that goes down. Alright, so Farnsworth, the carpenter, gets a little bit free and easy with killing crew members who don't cut it - one of them making rapey gestures towards Alice - and the carpenter and the lady start to fall in love with each other, even though it's pretty unmissably obvious to her and us that he's the... ghost? reincarnation? of Edward Ferd, the original builder of the Jarrets' new house, who started killing the repo men that came to take it over as he fussed on it so long that he ended up running out of money to construct it. Alice's sister Rachel (Barbara Ann Jones) shows up to add emotional support when the situation with Martin turns completely unlivable, and- but I could never dream of spoiling things! Save to say that the final line is a magnificent gleaming cherry on a towering sundae of ass-backwards storytelling, desperate stabs at thematic complexity, and deficient filmmaking.

I don't even know where to start with this. The low-hanging fruit is probably the gender argument: it's pretty clear that The Carpenter would like to be taken as a feminist statement (or at least, as a challenge to patriarchal authority), though it's equally clear that it has virtually no idea how to go about this. Heavy-handedness involving Martin's unbridled, and psychologically unlikely vileness, to begin with, including some really leering symbolism at the start when he lectures on Paul Bunyan as a symbol of North American masculinity at its most robust and exaggerated, only to be felled by technology, much like the technological advances that Martin and Edward Ferd themselves are... felled... actually, for all that this scene practically bruises your ribs, it's poking you so hard as it whispers "you get it, right? Martin is Paul Bunyan! Did you get that?", it's not really foreshadowing a goddamn thing, other than that symbols of the patriarchy abound in The Carpenter, and we're not meant to like them. As for the women who take their place, it's not entirely clear to me what kind of systematic ideology they stand in for; the film passes the Bechdel Test, anyway, though barely. And while Alice does emerge as the closest thing the movie has to a strong character, most of her personality is defined in terms of the husband she kind of hates or the sexy spectral carpenter she's falling for.

But that's not really touching much of anything. The meat of the film lies in its intensely bizarre thematic u-turns, and a style so overweening and ineffective that I must pull out a word that I do not like to use at all, "pretentious": and even then, I mean it only in a very narrow definition, which is that the film wants very much to be more than it can possibly manage to be on the budget and talent involved. Director David Wellington frequently indulges in visual schemes that are flat-out insane for a movie of this sort: flowing, grandiose pans and tracking shots that feel like they were made by somebody who has spent so much time studying the camerawork in Jean Renoir films that they have entirely forgotten why Renoir did what he did, and dissolves in place that dissolves are patently not called for: the whole thing is so baldly trying to be "artistic", without actually understanding artistry, that it's a little bit excruciating to watch, what with the film plodding along rather than building momentum. There's a stateliness and ponderous gravity to the visuals that neither the story nor the characters earn in the least.

Especially given how very silly this all is. Frankly, having watched it all the way through, I do not know if The Carpenter is secretly trying to be an absurdist comedy. There's a whole lot of evidence to that effect, of which I've already named some (the over-the-top caricature pretending to be a medical doctor), and even the overwrought camera directing can be though of as parody, if that's really what you want it to be. But there's so much else! I have pages of notes about things that could very seriously be looked on as self-mockery, like the scene where the carpenter, every time the shot-reverse shot sequence cuts back to him, is in the middle of a completely different task: cutting a board, hammering a nail, splitting a brick, cutting drywall, and planing a door, all in the span of 30 seconds. To the non-carpentry-inclined, it would be like showing a chef throwing dry pasta into boiling water, rolling out pie dough, shucking peas, and trimming fat off a steak all in quick succession. Or the obviously tongue-in-cheek death scenes, particularly the charmingly genteel conversation Ed and Alice have as he busily drills holes in a corpse. Or the nightmare where Alice witnesses Ed's penis replaced by a drill (which, tragically, is not shown onscreen). Or the conversation where Martin has small talk with Laura on the phone, trying not to raise Alice's suspicions, resulting in an indescribably arid minute or more of "ums" and "tell me more about thats".

It helps that Wings Hauser gives such a flighty, frivolously cheery performance, like a big overgrown gung-ho boy scout and handyman, that even as he absolutely dominates every single one of his scenes, he also strips of them of even the tiniest measure of serious impact. On the flipside, everybody else in the cast (except for Adams, arguably, doing the best she can with a part plagued by unusually stupid dialogue and unlikely motivations) is giving conventionally terrible performances, and if Hauser was at the heightened level he reaches through some deliberate scheme, surely anything else in the movie would be at that level with him? Besides, even if The Carpenter could be conclusively proven to be an immaculately straitlaced comedy, I still don't know if it would be funny, or what purpose it was all getting to.

No, better just to call it what it looks like; an exceptionally badly-made movie that's so damn loopy and weird that it's fun regardless of anything else. There's not much more you can demand of a late-80s pseudo-slasher (the paranormal and psychological aspects, as well as the '70s-style failing marriage framework, disguise what's ultimately a rather conventional psycho killer plot) than that it be fun; virtually none of them are, and even if The Carpenter comes by that accidentally and ironically, at least it's a crazy, thoroughly engaging piece of nuttery. There's energy to spare a dozen times over, and that alone makes it worthy of note in its genre, and its time.

Body Count: 6, plus a nail-gunned rat; not a huge total for the era, but for the film's relative domesticity, not bad.

Categories: canadian cinema, crimes against art, domestic dramas, good bad movies, horror, slashers, summer of blood