Not with a whimper, but a bang

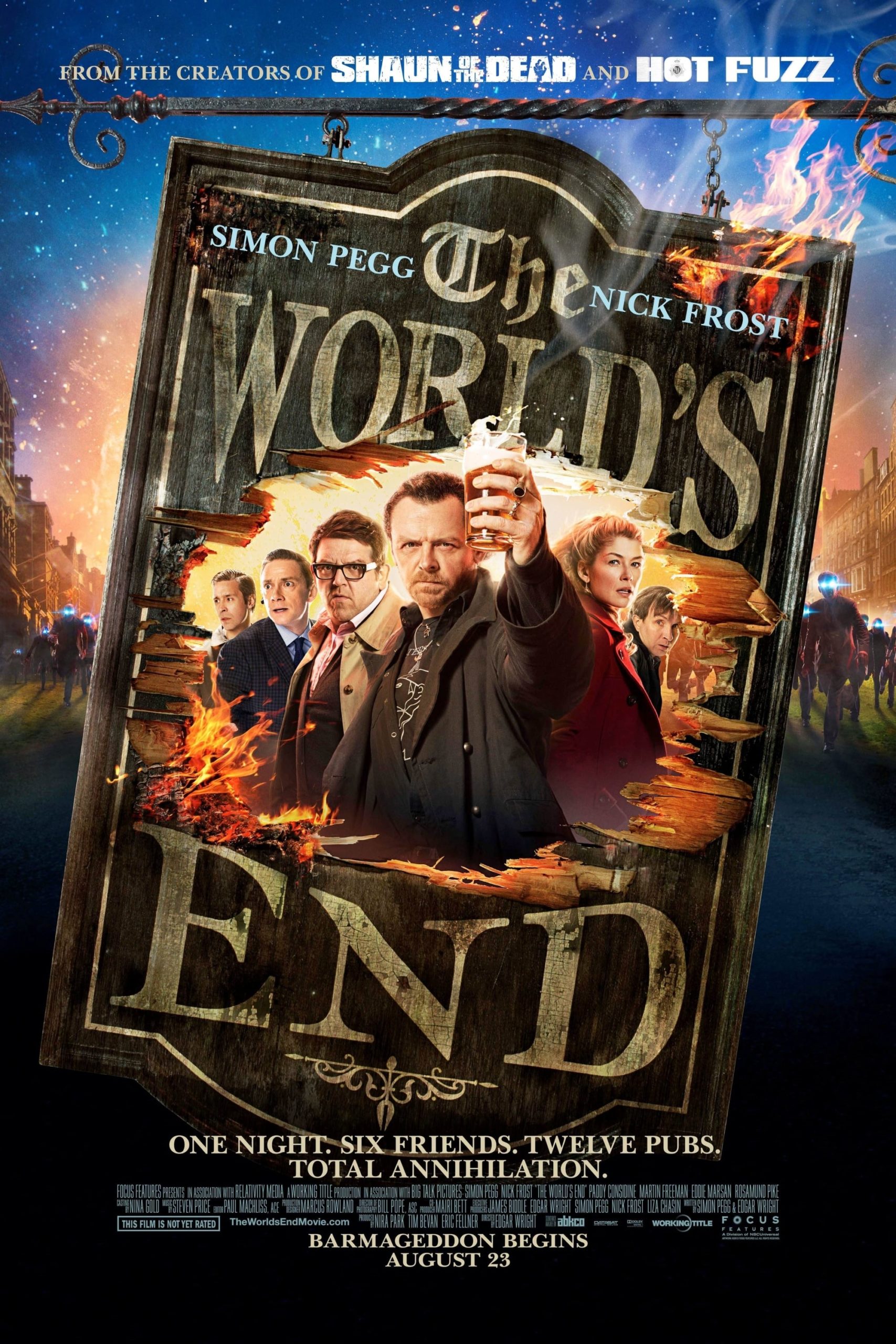

First, let's clear out the brush: The World's End, the third genre pastiche about English male behavior by Edgar Wright and Simon Pegg, just isn't as funny as Shaun of the Dead or Hot Fuzz. Even granting the deeply personal nature of what makes us laugh, I can't really imagine anybody thinking that claim is way off-base, though they might well disagree with it. Honestly, for lengthy stretches, it's not even evident that it's trying to be as funny as those films are; it's still enough to end up as the funniest thing I've seen in 2013 to this point, and barring something that unexpectedly turns out to be a massive gutbuster, it will remain that way by the time 2013 closes. But Shaun of the Dead and Hot Fuzz are, simply put, two of the funniest movies of the 2000s. That's a massive legacy to live up to, and it's not really shameful that The World's End doesn't.

The good news, on the flipside, is that The World's End is by a sizable degree the most complex and densest of the three movies, with so many delicate touches flashing flashing between the more obvious gestures of a script that has more going on thematically right there on the surface than the other two movies put together. Taken as a whole, the collection of movies called, more out of affection than descriptive accuracy, the "Cornetto Trilogy", dramatise the way that layabout males with affection for genre films - the trilogy's target audience, not to be blunt about it - are confronted with their own more-or-less immaturity and compelled to do something about it (or not); it's just that The World's End is so much more alert about this theme, grappling with it in an active, probing manner. Ultimately, the first two movies are both primarily genre comedies, into which a great deal of thoughtful observation about male behavior makes its way; this movie is a study of male behavior that uses genre film mechanics as one of its tools for attacking the topic. Which is perhaps why The World's End, unlike the first two, isn't really a parody of its genre; it's actually a very sincere alien body snatcher movie that happens to be funny rather than thrilling.

The way that the scenario is used as a metaphor for the message is apparent from even the most glancing description: many long years after his teenage heyday in 1990, Gary King (Pegg) hasn't progressed at all beyond his most hedonistic impulses, and so he decides to gather all his friends from that glorious time back for one last attempt at the epic 12-pub crawl that they failed to complete all those years ago. Problem is, none of those friends - care salesman Peter Page (Eddie Marsan), contractor Steven Prince (Paddy Considine), real estate agent Oliver Chamberlain (Martin Freeman), and especially Andy Knightley (Nick Frost, the reliable co-lead of all these films), a businessman so serious that the exact nature of his business is never spelled out - want anything to do with the selfish fuck-up that Gary has remained for more than 20 years, only coming along for his marathon bout of arrested development because he guilt trips them into it.

Once in their punishingly anonymous hometown of Newton Haven - a blank little British nowhere famous for having the first roundabout in the UK (the first of a great many things in the film that are metaphors if you want them to be, quaint details if you don't) - the five men discover the expected mixture of everything having changed and everything remaining the same, in the way that leads one to feel awfully unsettled about returning to a long-abandoned place, but the film's clever little generic switch (which comes a long way into the story, but since it shows up heavily in the ads, I take it to be fair game spoiler-wise) is that most of the city has been replaced by artificial bodies that do not take kindly to being called robots, the forefront of an alien invasion force that claims to want to make humankind better - but doesn't the monstrous, humanity-destroying alien hivemind always claim that?

When the whole thing is in motion for an hour and three quarters, it twists in directions that can barely be described, eventually ending up with the idea that maybe, steadfast immaturity isn't a terrible thing that only a dreadful prick would seek out; a piss-take of conventional character arcs that may or may not be serious (Wright's directorial career is filled with examples of men finding the right balance between growing up and maintaining their indulgent boyishness), but either way fits right into the sarcastic, biting edge that The World's End has to such great quantity. It is, at times, a genuinely melancholy film, leavening its immaculately-timed jokes with serious observations about how one can remain enthusiastic and have fun in the face of an increasingly homogenous world - one of the film's best jokes is at the expense of the "Starbucking" of small businesses, and one of its most piercing is about the constant plugged-in modern world and what that means for individual humans - with even Gary's shallow hedonism going deeper than just alcoholism and a fear of responsibility.

That this is funny at all speaks well of Wright's excellent handling of tone; but this is a truly marvelous collaborative effort. The cast is ludicrously strong, at almost every level (Rosamund Pike puts in a small but film-defining performance as a woman with a perpetual "are you fucking kidding me?" stare; Pierce Brosnan has a richly stentorian cameo, joining fellow ex-Bond Timothy Dalton in the series; the many tiny parts filled by non-famous actors are all perfect. And of course, the Big Five are all pretty terrific characters actors, enough so that it's impossible to pick a best in show, though Frost, at least, is doing the best work of his career by a landslide, playing an irritable straight man in various shades of righteous anger), and whether it's grounding the fantasy in some genuinely hard-hitting character detail, or simply playing the comedy perfectly, the film benefits immensely from every single person onscreen. Paul Machliss's editing is tight as a drum, including one scene set to the Doors' cover of "Alabama Song" that is a flawless gem showcasing how music, cutting, and physical performance can create comedy where absolutely none exists naturally (and for that matter, the soundtrack of pop songs, tied to Gary's solipsistic personal history, is one of the best put together for a film in years, adding energy and a sense of context).

Stunningly complex filmmaking all around, with a script to match, so dense that it's impossible to catch most of what's going on in one viewing - just picking out the way that the names of the 12 pubs in Gary's beloved crawl reflect the development of the story would take a viewing all to itself. It is smart, savvy, and too clever for words; maybe even too clever for its own good. It's easy to wish that this was all a bit breezier and more energetic, along the lines of its predecessors, which managed to be, in their way, nearly as deep without being anywhere near this much work to puzzle out. It's worth it, though: the film is rich and it is funny as hell, and that's a good combination from any angle. Could it be richer? funnier? Sure, I guess, but it's still the most inventive, humane comedy in ages, probably the best-directed action film of the summer, and easily the most intelligent science-fiction story in a year lousy with the damn things. It's not a masterpiece like Wright's earliest films, but it's still pretty great in its own right, serious without being solemn, merciless without being cruel, and the best excoriation of and tribute to men burying themselves that you could ever hope to see.

The good news, on the flipside, is that The World's End is by a sizable degree the most complex and densest of the three movies, with so many delicate touches flashing flashing between the more obvious gestures of a script that has more going on thematically right there on the surface than the other two movies put together. Taken as a whole, the collection of movies called, more out of affection than descriptive accuracy, the "Cornetto Trilogy", dramatise the way that layabout males with affection for genre films - the trilogy's target audience, not to be blunt about it - are confronted with their own more-or-less immaturity and compelled to do something about it (or not); it's just that The World's End is so much more alert about this theme, grappling with it in an active, probing manner. Ultimately, the first two movies are both primarily genre comedies, into which a great deal of thoughtful observation about male behavior makes its way; this movie is a study of male behavior that uses genre film mechanics as one of its tools for attacking the topic. Which is perhaps why The World's End, unlike the first two, isn't really a parody of its genre; it's actually a very sincere alien body snatcher movie that happens to be funny rather than thrilling.

The way that the scenario is used as a metaphor for the message is apparent from even the most glancing description: many long years after his teenage heyday in 1990, Gary King (Pegg) hasn't progressed at all beyond his most hedonistic impulses, and so he decides to gather all his friends from that glorious time back for one last attempt at the epic 12-pub crawl that they failed to complete all those years ago. Problem is, none of those friends - care salesman Peter Page (Eddie Marsan), contractor Steven Prince (Paddy Considine), real estate agent Oliver Chamberlain (Martin Freeman), and especially Andy Knightley (Nick Frost, the reliable co-lead of all these films), a businessman so serious that the exact nature of his business is never spelled out - want anything to do with the selfish fuck-up that Gary has remained for more than 20 years, only coming along for his marathon bout of arrested development because he guilt trips them into it.

Once in their punishingly anonymous hometown of Newton Haven - a blank little British nowhere famous for having the first roundabout in the UK (the first of a great many things in the film that are metaphors if you want them to be, quaint details if you don't) - the five men discover the expected mixture of everything having changed and everything remaining the same, in the way that leads one to feel awfully unsettled about returning to a long-abandoned place, but the film's clever little generic switch (which comes a long way into the story, but since it shows up heavily in the ads, I take it to be fair game spoiler-wise) is that most of the city has been replaced by artificial bodies that do not take kindly to being called robots, the forefront of an alien invasion force that claims to want to make humankind better - but doesn't the monstrous, humanity-destroying alien hivemind always claim that?

When the whole thing is in motion for an hour and three quarters, it twists in directions that can barely be described, eventually ending up with the idea that maybe, steadfast immaturity isn't a terrible thing that only a dreadful prick would seek out; a piss-take of conventional character arcs that may or may not be serious (Wright's directorial career is filled with examples of men finding the right balance between growing up and maintaining their indulgent boyishness), but either way fits right into the sarcastic, biting edge that The World's End has to such great quantity. It is, at times, a genuinely melancholy film, leavening its immaculately-timed jokes with serious observations about how one can remain enthusiastic and have fun in the face of an increasingly homogenous world - one of the film's best jokes is at the expense of the "Starbucking" of small businesses, and one of its most piercing is about the constant plugged-in modern world and what that means for individual humans - with even Gary's shallow hedonism going deeper than just alcoholism and a fear of responsibility.

That this is funny at all speaks well of Wright's excellent handling of tone; but this is a truly marvelous collaborative effort. The cast is ludicrously strong, at almost every level (Rosamund Pike puts in a small but film-defining performance as a woman with a perpetual "are you fucking kidding me?" stare; Pierce Brosnan has a richly stentorian cameo, joining fellow ex-Bond Timothy Dalton in the series; the many tiny parts filled by non-famous actors are all perfect. And of course, the Big Five are all pretty terrific characters actors, enough so that it's impossible to pick a best in show, though Frost, at least, is doing the best work of his career by a landslide, playing an irritable straight man in various shades of righteous anger), and whether it's grounding the fantasy in some genuinely hard-hitting character detail, or simply playing the comedy perfectly, the film benefits immensely from every single person onscreen. Paul Machliss's editing is tight as a drum, including one scene set to the Doors' cover of "Alabama Song" that is a flawless gem showcasing how music, cutting, and physical performance can create comedy where absolutely none exists naturally (and for that matter, the soundtrack of pop songs, tied to Gary's solipsistic personal history, is one of the best put together for a film in years, adding energy and a sense of context).

Stunningly complex filmmaking all around, with a script to match, so dense that it's impossible to catch most of what's going on in one viewing - just picking out the way that the names of the 12 pubs in Gary's beloved crawl reflect the development of the story would take a viewing all to itself. It is smart, savvy, and too clever for words; maybe even too clever for its own good. It's easy to wish that this was all a bit breezier and more energetic, along the lines of its predecessors, which managed to be, in their way, nearly as deep without being anywhere near this much work to puzzle out. It's worth it, though: the film is rich and it is funny as hell, and that's a good combination from any angle. Could it be richer? funnier? Sure, I guess, but it's still the most inventive, humane comedy in ages, probably the best-directed action film of the summer, and easily the most intelligent science-fiction story in a year lousy with the damn things. It's not a masterpiece like Wright's earliest films, but it's still pretty great in its own right, serious without being solemn, merciless without being cruel, and the best excoriation of and tribute to men burying themselves that you could ever hope to see.

Categories: action, british cinema, comedies, science fiction, summer movies