Summer of Blood: Be there or be square

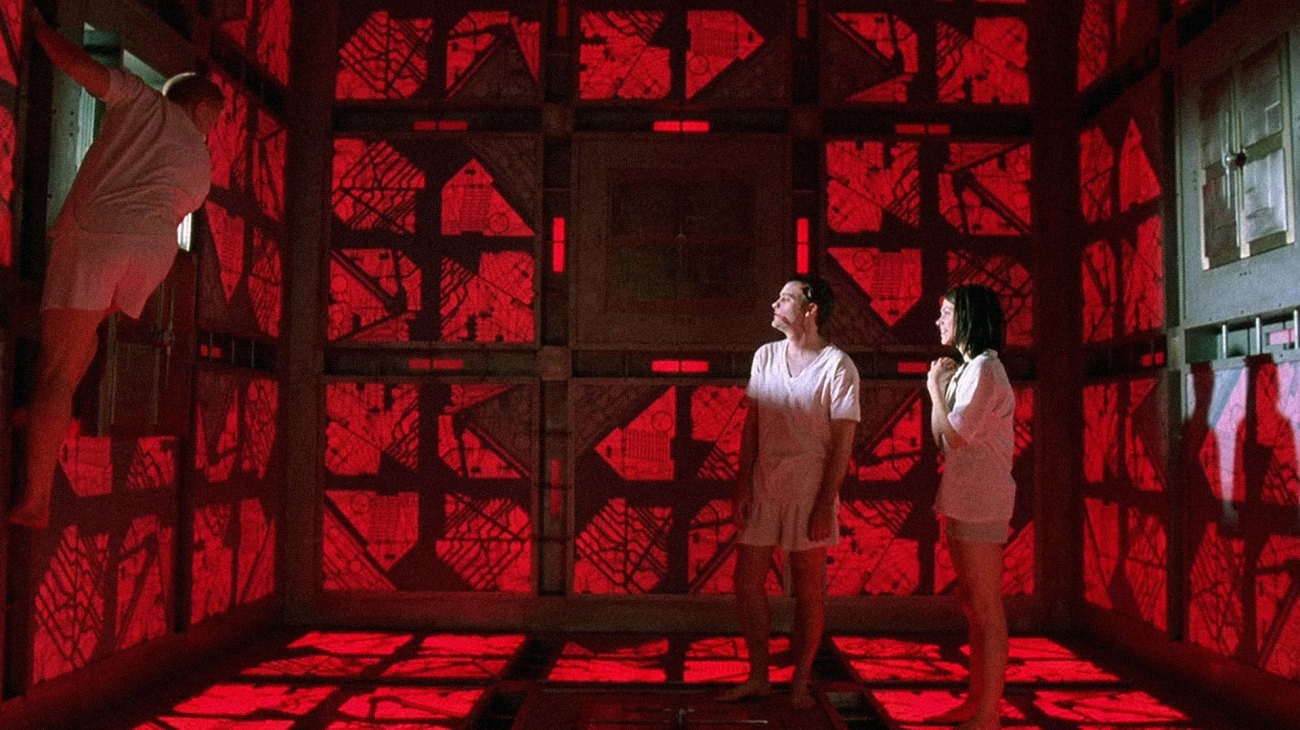

There's much to say about Cube, a 1997 sci-fi horror film and philosophically-laden mindfuck by director Vincenzo Natali, but before I get into any of that, a word of praise. Because this, this is how you do a low-budget movie. Only enough resources to build one cube-shaped room? Then build that cube-shaped room as best as you possibly can, make it as simple but strange-looking as you dare, and use colored gels to change the color of it. Bingo, you have an infinite-number of cube-shaped rooms, and you never need to show more than three 14-foot square panels on camera at any one moment. Of course, the problem there is coming up with a scenario that needs an infinite number of cube-shaped rooms...

What Natali and co-writers André Bijelic and Graeme Manson came up with is a sleek, simple affair, heavy on abstraction in the fashion of a Twilight Zone episode (indeed, specific Twilight Zone episodes occasionally flitted across my mind as I was watching). Not immediately. The opening scene is a fairly tepid bit of structural cliché, as a bald man whose name, if you hang around for the credits, is given as Alderson (Julian Richings), wakes up in a bright white room where every plane is covered in a 3' by 3' grid of squares full of inexplicable, vaguely circuit-looking designs, each face with a heavy metal hatch in the middle. Alderson goes through one of these hatches, into an identical room, save that it is peach-colored; as he gawks, a mesh of razor wire sweeps quickly down from the ceiling, cutting through him cleanly and turning him into a pile of, well, cubes. I call this a cliché not because of its content, but because nothing here ever remotely informs the rest of the plot; it's just a way to quickly establish that the cube rooms are full of deadly evil, and also to provide an early boost of queasy-making violence in a film where hardly any actual gore shows up. It's every slasher film opening scene of the '80s, and Cube is far too interesting to require such a junky gesture.

We return to the white room - or another white room? - for the film to assemble its actual cast. First up is the bloody hand of a man emerging from a red room below the white room (I said there was a hatch in every plane of the room, don't forget), and this turns out to be Quentin (Maurice Dean Wint), as we first learn from his drab jumpsuit, blank except for a name on the left breast. Such jumpsuits will be a convenient way for Quentin to meet the rest of his fellow prisoners, as they stumble into his white room: middle-aged woman Holloway (Nicky Guadagni), wizened old man Rennes (Wayne Robson), thirtyish man Worth (David Hewlett), young woman Leaven (Nicole de Boer, making her second Summer of Blood appearance in a row, after headlining Prom Night IV: Deliver Us from Evil). Eventually, after this band maneuvers through the maze, losing one person to an acid bath in the face in the process, they'll meet one more lost soul: Kazan (Andrew Miller), a mentally challenged man.

Attempting to synopsise what happens from that point on would be frivolous: what passes for plot Cube is the scene in which the five travelers attempt to determine which direction they need to go next, frequently kicking off some very, very good thriller setpieces in which there may be a trap, or there very definitely is a trap, and it has to be gotten through. Meanwhile, Leaven uses her considerable mathematical skill to attempt to puzzle out the serial numbers inside every hatch, twice concluding that she's figured out how to map the great complex of cubes that they're all tunneling through, and twice being wrong. As sleeplessness, hunger, and fear gnaw at the prisoners - a word that applies even if the film never comes closer to explicitly calling this a prison than in the cutesy-poo names of the characters - they drift inexorably from unresolved conversations about how and why and at whose hand they've ended up here, into unresolved fights about which among them is the worst, stupidest, most useless person.

And the thing is, you can't make that sound interesting - "for 90 minutes, people move through largely identical cubic rooms that want to kill them". But it is interesting, mainly, and here's where the Twilight Zone comparison is useful. See, even with the very limited information we get about the characters throughout the movie (mostly just their occupation, if that - "unspecified developmental disorder" is the entirety of what we learn about Kazan), or perhaps because it's so limited, the cast ends up filling somewhat allegorical roles: the Teacher, the Authoritarian, the Intellect, the Survivalist. And Cube, in finest Rod Serling fashion, plays out as a series of conundrums in which the audience is invited to think about how these different types, that is to say, these different worldviews and moral codes, interact with each other in a patently allegorical environment: a monstrous Building Project Run Amok, ordered by no-one to serve no purpose, a mechanical hell of faceless modernity. The audience is invited, at various times, to agree with different people: sometimes Quentin seems to be the only reasonable man in the face of wishy-washy morons, but then he turns out to be a thug and bully. Holloway alternates between laughably paranoid and totally justified almost every scene. Leaven is sometimes clever, sometimes dangerously myopic. You can take this all as allegory, or (as I prefer to do, with my general mistrust of allegory and symbolism) simply as a bunch of very different personalities butting heads in a situation where that is the absolute worst thing to do, and shake your head in dismay at human nature.

The most complex and interesting of the characters is Worth, suicidally depressed at first, totally without hope always. He frustratedly describes his life as "I work in an office building, doing office building stuff", a line that comes back in a haunting way about halfway through the film (HALFWAY THROUGH FILM SPOILER), when we learn that his job included designing the cubic outer shell housing the very complex where he now finds himself. It's where the allegory shines brightest, with the prototypical modern job in an information economy - sitting behind a desk, doing nothing that holds up to much description - an instrument of an identity-free bureaucracy that exists only to cause pointless suffering. One does not expect a low-budget genre hybrid to end up embodying, even accidentally, Hannah Arendt's idea of the banality of evil, but this is exactly what Cube ends up doing.

There are two different ways in which the film could said to fall flat: the one that doesn't interest me much is its conceptual failures. This is, again, a Twilight Zone-style study of human archetypes in a metaphorical setting, even if it has heavy sci-fi and horror and thriller trappings, and any hope that its mysteries will prove soluble (or even that it merely offers up much in the way of meat to speculate on) end up totally thwarted. Similarly, the question, "how does the Cube even work?" is beyond the filmmakers' interests at all. This is a parable, not a realist narrative, and there are always going to be those for whom that kind of thing is going to end up being too frustrating.

Cube also suffers from failures of execution, and this I will not wave away. Basically, the acting here is not very good: only the wide-eyed de Boer is acutely bad throughout, and Guadagni frequently oversells her lines like an eager community theater actor, while the men are mostly just flat and boring. Wint, I concede, is mostly good right up to the scene where he officially jumps from "rational but mean" to "outright psycho", and the actor takes that as a cue to ham it up. Allegory or not, there's no reason for the human characters to seem so bland and caricatured as these performers make them.

And allegory or not, there's some dopey writing that needn't be there: most appallingly, a third act Resurrected Killer moment that the film would be vastly improved without, it being not just a cliché whose time had long since expired in '97, but a cliché for an entirely different kind of story in the first place. What actually bothered me more, though, was the way that supposed math genius Leaven had to sweat over determining prime numbers, having not apparently learned the easy trick that any even number is divisible by 2, and any number ending in 5 is divisible by 5, so you don't actually have to spent half a minute factoring them. Strictly a nitpick, but it's always the little details that are just flat-out wrong that really break the illusion of a film's reality, even when that reality is this surreal.

On the other hand, look at all the things that the film gets right! If for nothing but the crackling tension of a scene where the party has to sneak through a blue room where even the tiniest sound fills the entire space with razor-sharp spines, Natali's handling of mood and pace would leave Cube one of the tightest horror-thrillers of the late '90s, which isn't actually a compliment when you stop and think about late '90s horror-thrillers, but I meant for it to come off like one (the one time that everything goes to hell: a montage in which the characters blast through a whole chain of rooms safely, with the images, editing, and sound design conspiring to make everything seem utterly stupid). And while that is a great scene, it is not the only great scene, maybe not even the best scene: a chase scene that has to tarry while Leaven laboriously determines which door is the safe route out, and the casually startling second death are both right up near the top as well. More generally, the director also manages to make the lengthy "can we, like, please talk about ethical philosphy?" scenes play onscreen far better than I can possibly imagine that they did on the page, though nothing at all can make the really hefty one about 35 minutes in feel like anything but an exercise in late-night dorm room bull session monologuing.

Most impressively of all, Natali and his great team of cinematographer Derek Rogers, editor John Sanders, and production designer Jasna Stefanovic did a simply killer job of presenting the endless, repetitive cube rooms in such a way that completely disguises the cheap, stagebound nature of the affair. When one slows down to consider the amount of energy and planning that had to go into setting up shots and piecing them together and focusing on just the right bits of the walls to make sure that scenes would flow right, and transition from one to the other properly, Cube can only be regarded as a titanic masterpiece of resource management. That's just about the least sexy thing you could ever praise a filmmaker for doing, but making the movie this seamless required tremendous skill and attention, and at the level of pure craftsmanship, Cube is among the most genuinely impressive low-budget films that I have ever seen.

Body Count: 6, which you will note is a healthy percentage of the 7-person cast.

What Natali and co-writers André Bijelic and Graeme Manson came up with is a sleek, simple affair, heavy on abstraction in the fashion of a Twilight Zone episode (indeed, specific Twilight Zone episodes occasionally flitted across my mind as I was watching). Not immediately. The opening scene is a fairly tepid bit of structural cliché, as a bald man whose name, if you hang around for the credits, is given as Alderson (Julian Richings), wakes up in a bright white room where every plane is covered in a 3' by 3' grid of squares full of inexplicable, vaguely circuit-looking designs, each face with a heavy metal hatch in the middle. Alderson goes through one of these hatches, into an identical room, save that it is peach-colored; as he gawks, a mesh of razor wire sweeps quickly down from the ceiling, cutting through him cleanly and turning him into a pile of, well, cubes. I call this a cliché not because of its content, but because nothing here ever remotely informs the rest of the plot; it's just a way to quickly establish that the cube rooms are full of deadly evil, and also to provide an early boost of queasy-making violence in a film where hardly any actual gore shows up. It's every slasher film opening scene of the '80s, and Cube is far too interesting to require such a junky gesture.

We return to the white room - or another white room? - for the film to assemble its actual cast. First up is the bloody hand of a man emerging from a red room below the white room (I said there was a hatch in every plane of the room, don't forget), and this turns out to be Quentin (Maurice Dean Wint), as we first learn from his drab jumpsuit, blank except for a name on the left breast. Such jumpsuits will be a convenient way for Quentin to meet the rest of his fellow prisoners, as they stumble into his white room: middle-aged woman Holloway (Nicky Guadagni), wizened old man Rennes (Wayne Robson), thirtyish man Worth (David Hewlett), young woman Leaven (Nicole de Boer, making her second Summer of Blood appearance in a row, after headlining Prom Night IV: Deliver Us from Evil). Eventually, after this band maneuvers through the maze, losing one person to an acid bath in the face in the process, they'll meet one more lost soul: Kazan (Andrew Miller), a mentally challenged man.

Attempting to synopsise what happens from that point on would be frivolous: what passes for plot Cube is the scene in which the five travelers attempt to determine which direction they need to go next, frequently kicking off some very, very good thriller setpieces in which there may be a trap, or there very definitely is a trap, and it has to be gotten through. Meanwhile, Leaven uses her considerable mathematical skill to attempt to puzzle out the serial numbers inside every hatch, twice concluding that she's figured out how to map the great complex of cubes that they're all tunneling through, and twice being wrong. As sleeplessness, hunger, and fear gnaw at the prisoners - a word that applies even if the film never comes closer to explicitly calling this a prison than in the cutesy-poo names of the characters - they drift inexorably from unresolved conversations about how and why and at whose hand they've ended up here, into unresolved fights about which among them is the worst, stupidest, most useless person.

And the thing is, you can't make that sound interesting - "for 90 minutes, people move through largely identical cubic rooms that want to kill them". But it is interesting, mainly, and here's where the Twilight Zone comparison is useful. See, even with the very limited information we get about the characters throughout the movie (mostly just their occupation, if that - "unspecified developmental disorder" is the entirety of what we learn about Kazan), or perhaps because it's so limited, the cast ends up filling somewhat allegorical roles: the Teacher, the Authoritarian, the Intellect, the Survivalist. And Cube, in finest Rod Serling fashion, plays out as a series of conundrums in which the audience is invited to think about how these different types, that is to say, these different worldviews and moral codes, interact with each other in a patently allegorical environment: a monstrous Building Project Run Amok, ordered by no-one to serve no purpose, a mechanical hell of faceless modernity. The audience is invited, at various times, to agree with different people: sometimes Quentin seems to be the only reasonable man in the face of wishy-washy morons, but then he turns out to be a thug and bully. Holloway alternates between laughably paranoid and totally justified almost every scene. Leaven is sometimes clever, sometimes dangerously myopic. You can take this all as allegory, or (as I prefer to do, with my general mistrust of allegory and symbolism) simply as a bunch of very different personalities butting heads in a situation where that is the absolute worst thing to do, and shake your head in dismay at human nature.

The most complex and interesting of the characters is Worth, suicidally depressed at first, totally without hope always. He frustratedly describes his life as "I work in an office building, doing office building stuff", a line that comes back in a haunting way about halfway through the film (HALFWAY THROUGH FILM SPOILER), when we learn that his job included designing the cubic outer shell housing the very complex where he now finds himself. It's where the allegory shines brightest, with the prototypical modern job in an information economy - sitting behind a desk, doing nothing that holds up to much description - an instrument of an identity-free bureaucracy that exists only to cause pointless suffering. One does not expect a low-budget genre hybrid to end up embodying, even accidentally, Hannah Arendt's idea of the banality of evil, but this is exactly what Cube ends up doing.

There are two different ways in which the film could said to fall flat: the one that doesn't interest me much is its conceptual failures. This is, again, a Twilight Zone-style study of human archetypes in a metaphorical setting, even if it has heavy sci-fi and horror and thriller trappings, and any hope that its mysteries will prove soluble (or even that it merely offers up much in the way of meat to speculate on) end up totally thwarted. Similarly, the question, "how does the Cube even work?" is beyond the filmmakers' interests at all. This is a parable, not a realist narrative, and there are always going to be those for whom that kind of thing is going to end up being too frustrating.

Cube also suffers from failures of execution, and this I will not wave away. Basically, the acting here is not very good: only the wide-eyed de Boer is acutely bad throughout, and Guadagni frequently oversells her lines like an eager community theater actor, while the men are mostly just flat and boring. Wint, I concede, is mostly good right up to the scene where he officially jumps from "rational but mean" to "outright psycho", and the actor takes that as a cue to ham it up. Allegory or not, there's no reason for the human characters to seem so bland and caricatured as these performers make them.

And allegory or not, there's some dopey writing that needn't be there: most appallingly, a third act Resurrected Killer moment that the film would be vastly improved without, it being not just a cliché whose time had long since expired in '97, but a cliché for an entirely different kind of story in the first place. What actually bothered me more, though, was the way that supposed math genius Leaven had to sweat over determining prime numbers, having not apparently learned the easy trick that any even number is divisible by 2, and any number ending in 5 is divisible by 5, so you don't actually have to spent half a minute factoring them. Strictly a nitpick, but it's always the little details that are just flat-out wrong that really break the illusion of a film's reality, even when that reality is this surreal.

On the other hand, look at all the things that the film gets right! If for nothing but the crackling tension of a scene where the party has to sneak through a blue room where even the tiniest sound fills the entire space with razor-sharp spines, Natali's handling of mood and pace would leave Cube one of the tightest horror-thrillers of the late '90s, which isn't actually a compliment when you stop and think about late '90s horror-thrillers, but I meant for it to come off like one (the one time that everything goes to hell: a montage in which the characters blast through a whole chain of rooms safely, with the images, editing, and sound design conspiring to make everything seem utterly stupid). And while that is a great scene, it is not the only great scene, maybe not even the best scene: a chase scene that has to tarry while Leaven laboriously determines which door is the safe route out, and the casually startling second death are both right up near the top as well. More generally, the director also manages to make the lengthy "can we, like, please talk about ethical philosphy?" scenes play onscreen far better than I can possibly imagine that they did on the page, though nothing at all can make the really hefty one about 35 minutes in feel like anything but an exercise in late-night dorm room bull session monologuing.

Most impressively of all, Natali and his great team of cinematographer Derek Rogers, editor John Sanders, and production designer Jasna Stefanovic did a simply killer job of presenting the endless, repetitive cube rooms in such a way that completely disguises the cheap, stagebound nature of the affair. When one slows down to consider the amount of energy and planning that had to go into setting up shots and piecing them together and focusing on just the right bits of the walls to make sure that scenes would flow right, and transition from one to the other properly, Cube can only be regarded as a titanic masterpiece of resource management. That's just about the least sexy thing you could ever praise a filmmaker for doing, but making the movie this seamless required tremendous skill and attention, and at the level of pure craftsmanship, Cube is among the most genuinely impressive low-budget films that I have ever seen.

Body Count: 6, which you will note is a healthy percentage of the 7-person cast.