The 49th Chicago International Film Festival

Screens at CIFF: 10/21 & 10/23

World premiere: 19 May, 2013, Cannes International Film Festival

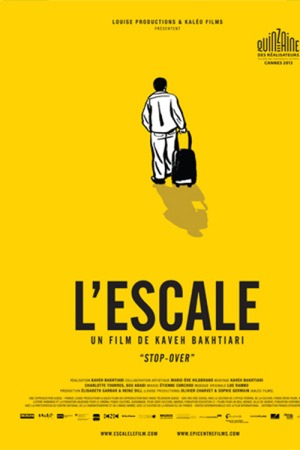

The documentary Stop-Over begins with what's far too swift and deadly to call it a sucker punch: more like a stiletto darted into the heart. Kaveh Bakhtiari's first feature-length project starts with a filmed conversation about the rough life of an illegal emigrant from the Middle East to Europe, with the director filming his cousin Mohsen. This segues into a series of title cards, explaining that Mohsen was with a group of fellow travelers three years ago, back when he hadn't yet decided to give up and return to Iran, back when he was still alive. And just like that, with that dumbfounding "still", the movie assumes for itself a sense of overwhelming fatalism that clings to it for the rest of its 106 minutes, giving a film with a kaleidoscopic view of the lives of several immigrants a very specific human story to tether it.

Bakhtiari spent quite a long time visiting Mohsen in Athens (a common layover point for illegal immigration), when Mohsen was living in a rooming house of sorts with a circle of hopeful immigrants, loosely led by a man of about 30 or 35 named Amir (sensibly, the director refrains from family names). The director was himself a Swiss citizen and thus detached from the reality lived by these people, too broken by life in their native country to feel like they could ever return to the unspoken agonies they've escaped from, and unable to find any legal channel to escape to something better. And so does Stop-Over take the form of a fly-on-the-wall piece of observation, watching as the men (and one woman) come and go, hanging on to whatever measure of hope they're able to scrounge up, mostly letting their daily lives play out without connection to greater narratives about The Immigrant Experience, and mostly eschewing political commentary - by no means are Bakhtiari's political sympathies in doubt, you understand, and by its very nature Stop-Over can't help but by a rallying cry. But it's also not a message movie of any sort, arguing only that these people, so easily written off with the word "illegal", have human feelings and motivations not so readily pigeonholed.

At the same time, Bakhtiari's separation from his subjects remains an ever-present sticking point: explicitly identified only a few times, but always there in the way that his camera eye puts a wal between his experience and theirs - we never see Bakhtiari interacting with the people he spends quite a lot of time living with, and when they make a specific point of engaging with him, it's almost always to stress his otherness, whether because of his camera (which annoys some people more often than others), or because his legal status puts him in a position to do things and speak to people that they cannot. There aren't but two or three moments in the 106-minute film where there's overt resentment, but there's not a single moment where Bakhtiaria seems to really "belong".

This curious relationship between director and his subjects results in Stop-Over having an objectivity to it that's really quite striking. Not about the ramifications of the situation being filmed - as I said, even if he doesn't ventriloquise it, there's no doubt that Bakhtiari firmly believes that every single person who goes before his camera deserve the full rights of citizenship wherever they want to go. It is, however, objective about who they are and how they live: the film's chief value is undoubtedly how it captures the day-to-day life of people living in reduced circumstances and under profound stress. It's a journalistic presentation of life on the edge, most beautifully summed up by a 16-year-old (the film's most reliably freaked-out inhabitant; in one amusing moment, Amir is pleased to find out how much calmer he is on tranquilisers) who observes that all his dreams are of being chased by the police. The film is a marvelous depiction of normal life in profoundly abnormal situations, and it doesn't take political sympathy to see how interesting all this is.

As good as all this is, Stop-Over suffers from one serious and pervasive limitation that significantly reduces its potency, and possibly could not be fixed without breaking the wonderful intimacy with which Bakhtiari represents his subjects. Basically, the film lacks context: it's so concerned with the "this is what happens today" scale, it loses sight entirely of the "this is what happened yesterday and what will happen tomorrow" of the material, and since is the survival mechanism adopted by the immigrants themselves, this makes sense. But it is, maybe, the documentarian's job to expand on the limited viewpoint of his material, and this is not something Bakhtiari does: everything from the overall scope of immigration policy to the simple fact that Athens is a hotbed of illegal immigration is are either implied or left totally unstated, and there's really not any attempt to connect the lives of these people to the world outside of this rooming house. It's all noble, engaging, and humanist, but it's frustratingly minor, and I feel like even just five minutes of more impersonal exposition might have given Stop-Over quite a bit more heft as sociology and political tract.

7/10

World premiere: 19 May, 2013, Cannes International Film Festival

The documentary Stop-Over begins with what's far too swift and deadly to call it a sucker punch: more like a stiletto darted into the heart. Kaveh Bakhtiari's first feature-length project starts with a filmed conversation about the rough life of an illegal emigrant from the Middle East to Europe, with the director filming his cousin Mohsen. This segues into a series of title cards, explaining that Mohsen was with a group of fellow travelers three years ago, back when he hadn't yet decided to give up and return to Iran, back when he was still alive. And just like that, with that dumbfounding "still", the movie assumes for itself a sense of overwhelming fatalism that clings to it for the rest of its 106 minutes, giving a film with a kaleidoscopic view of the lives of several immigrants a very specific human story to tether it.

Bakhtiari spent quite a long time visiting Mohsen in Athens (a common layover point for illegal immigration), when Mohsen was living in a rooming house of sorts with a circle of hopeful immigrants, loosely led by a man of about 30 or 35 named Amir (sensibly, the director refrains from family names). The director was himself a Swiss citizen and thus detached from the reality lived by these people, too broken by life in their native country to feel like they could ever return to the unspoken agonies they've escaped from, and unable to find any legal channel to escape to something better. And so does Stop-Over take the form of a fly-on-the-wall piece of observation, watching as the men (and one woman) come and go, hanging on to whatever measure of hope they're able to scrounge up, mostly letting their daily lives play out without connection to greater narratives about The Immigrant Experience, and mostly eschewing political commentary - by no means are Bakhtiari's political sympathies in doubt, you understand, and by its very nature Stop-Over can't help but by a rallying cry. But it's also not a message movie of any sort, arguing only that these people, so easily written off with the word "illegal", have human feelings and motivations not so readily pigeonholed.

At the same time, Bakhtiari's separation from his subjects remains an ever-present sticking point: explicitly identified only a few times, but always there in the way that his camera eye puts a wal between his experience and theirs - we never see Bakhtiari interacting with the people he spends quite a lot of time living with, and when they make a specific point of engaging with him, it's almost always to stress his otherness, whether because of his camera (which annoys some people more often than others), or because his legal status puts him in a position to do things and speak to people that they cannot. There aren't but two or three moments in the 106-minute film where there's overt resentment, but there's not a single moment where Bakhtiaria seems to really "belong".

This curious relationship between director and his subjects results in Stop-Over having an objectivity to it that's really quite striking. Not about the ramifications of the situation being filmed - as I said, even if he doesn't ventriloquise it, there's no doubt that Bakhtiari firmly believes that every single person who goes before his camera deserve the full rights of citizenship wherever they want to go. It is, however, objective about who they are and how they live: the film's chief value is undoubtedly how it captures the day-to-day life of people living in reduced circumstances and under profound stress. It's a journalistic presentation of life on the edge, most beautifully summed up by a 16-year-old (the film's most reliably freaked-out inhabitant; in one amusing moment, Amir is pleased to find out how much calmer he is on tranquilisers) who observes that all his dreams are of being chased by the police. The film is a marvelous depiction of normal life in profoundly abnormal situations, and it doesn't take political sympathy to see how interesting all this is.

As good as all this is, Stop-Over suffers from one serious and pervasive limitation that significantly reduces its potency, and possibly could not be fixed without breaking the wonderful intimacy with which Bakhtiari represents his subjects. Basically, the film lacks context: it's so concerned with the "this is what happens today" scale, it loses sight entirely of the "this is what happened yesterday and what will happen tomorrow" of the material, and since is the survival mechanism adopted by the immigrants themselves, this makes sense. But it is, maybe, the documentarian's job to expand on the limited viewpoint of his material, and this is not something Bakhtiari does: everything from the overall scope of immigration policy to the simple fact that Athens is a hotbed of illegal immigration is are either implied or left totally unstated, and there's really not any attempt to connect the lives of these people to the world outside of this rooming house. It's all noble, engaging, and humanist, but it's frustratingly minor, and I feel like even just five minutes of more impersonal exposition might have given Stop-Over quite a bit more heft as sociology and political tract.

7/10

Categories: ciff, documentaries, french cinema, political movies, swiss cinema