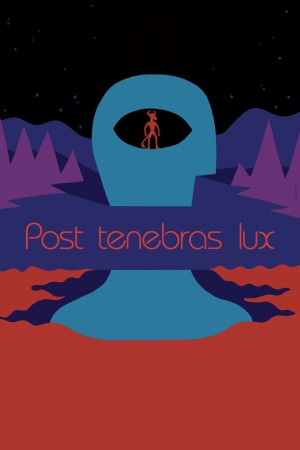

After darkness, ligth

There is a certain type of film, destined to never move beyond the art house, so challenging and unconventional in its storytelling and visual vocabulary that it needs to train the adventuresome viewer how to watch it, in the act of watching it. Carlos Reygadas's fourth feature, Post Tenebras Lux, is not that kind of film. It's at the next level: it's so challenging and unconventional that it doesn't even train us how to watch itself, but simply blasts forward and doesn't care whether or not we're hanging on. It's the sort of thing that, though it looks like a narrative film in many particulars, probably doesn't actually qualify as one, working rather as an abstraction.

Indeed, watching it, one doesn't first think of how it relates to other movies (not even to Reygadas's own, though it spends a lot of time in the middle in a similar register to Battle in Heaven and especially Silent Light), but of how it relates to other visual art forms: in particular, the film resembles Impressionist painting in a lot of ways, mostly to do with it bends and warps the image to create a certain emotional mood not from anything to do with what is being depicted, but entirely because of how it is being depicted. Most of the exteriors are shot with a wider-than-usual lens, that has had a kind of distorting filter applied to the edges, all in a circle, and this makes anything on the edge of the frame (a frame in the 1.33:1 aspect ratio, I might add, which already puts the film comfortably on my good side) split and refract, so that it looks like any moving object is followed by its own ghost. Reygadas has suggested the intent was to make the images look as they might if you were watching them through an old windowpane, and I can definitely see what he's getting at there.

But it doesn't take something as specific as that image to understand what the images are attempting to convey: a certain separation from the material born of nostalgia (the film acts as a slantwise autobiography, but I think that any attempt to chase it down that way is doomed to severely misrepresenting what the film is), and mired in a perspective that doesn't quite understand what's going on literally, nor in a strictly chronological fashion, but is certainly capable of following along with the ebb and flow of mood. The movie opens with a barnburner of a shot in which a little girl, Rut (Rut Reygadas, the director's child) is hastening around a rural yard, chatting enthusiastically with the animals around her, as the sky grows positively apocalypstic in its overcast gloom, and the shot is incredibly anxious for us to occupy the perspective of a very small child, looking right at her (or even up a tiny bit), and to spend a good long time wrapped up in her headspace. Is Post Tenebras Lux meant to be understood as a film from a child's perspective, with its ellipses standing in for the ways that a child fails to understand everything that happens around her? It's hard to say - that's certainly one of many readings available to us.

But even asking the question assumes that there's a way to "solve" Post Tenebras Lux, and one of the things that I think we need to accept about the film is that there simply isn't such a thing as a "solution". This is a movie of impressions and attitudes; it is an emphatically and specifically religious film as well, in which the Devil or something like it is an active figure, personal failures are specifically considered to be sins, in an acutely spiritual (though not specifically Catholic) sense, and an evocative sense of mysticism is laid over the film's very best moments, including the plunge into flickering blackness that follows Rut's merry run around the yard. I think it's absolutely fair to say, in fact, that the biggest problem with Post Tenebras Lux is that it spends far too much time outside of the explicitly spiritual and mystical register established in its opening 20 minutes, with the most literal interpretation of the title, and a utterly breathtaking scene of the Devil, a featureless red space in human form, deliberately stalking through a family's home.

The film actually spends most of its time in a wholly different mode, functioning variably as a study of one family: Juan (Adolfo Jiménez Castro), Natalia (Nathalia Acevedo), and their children, Rut and Eleazar (Eleazar Reygadas), with frequent layovers in scenes that don't have anything to do with any of them. At its worse, the film basically retreads the aesthetic of Silent Light, letting the domestic drama play out in mercilessly long, still moments where the camera soaks up action in something that we might call a naturalistic mode if there was anything even marginally naturalistic about the staging or performances in the film. At its best, it is a phenomenally effective tone poem about good and evil, though I think it should be said that Reygadas's apparent definition of "evil" is more reactionary and unforgiving than mine is; in addition to the film's almost melodramatic fear of sex, there's a repeated motif about addiction and recovery that suggests that human weakness is evil, or at least symptomatic of it, which is a bit harsher and less forgiving than I care for my spiritual allegories to be (I'd contrast the film to The Tree of Life, just about the only thematic mate I can think of in recent cinema, where human weakness is treated with love and understanding and overcome with joy, not with moralising).

That's nitpicking though, and of a particularly weird sort. Frankly, being in a position where I feel like I'm debating religion with a filmmaker because of his movie is so exciting that I don't know what to do with it, and that's enough to make Post Tenebras Lux a completely essential piece of film art. Talking about it in terms of artistic effectiveness is simply bizarre, because the film is far enough away from anything covered by rules that it can't rightly be said to break them or not; I wish mightily that middle was as good as the opening 20 minutes and the beautifully out-of-nowhere but thematically ripe final scene, but that's sort of immaterial. Post Tenebras Lux is an experiment in expressing a religious feeling through cinema, and though the experiment could have been more successful, who else would think to make it? It's not enough to clearly mark Reygadas as one of our best filmmakers in the world right now, but he's easily one of the most essential, and I can think of no reason not to assume that's just as good

[X]/10, though if you made me put a number on it, that number would probably be 8

Indeed, watching it, one doesn't first think of how it relates to other movies (not even to Reygadas's own, though it spends a lot of time in the middle in a similar register to Battle in Heaven and especially Silent Light), but of how it relates to other visual art forms: in particular, the film resembles Impressionist painting in a lot of ways, mostly to do with it bends and warps the image to create a certain emotional mood not from anything to do with what is being depicted, but entirely because of how it is being depicted. Most of the exteriors are shot with a wider-than-usual lens, that has had a kind of distorting filter applied to the edges, all in a circle, and this makes anything on the edge of the frame (a frame in the 1.33:1 aspect ratio, I might add, which already puts the film comfortably on my good side) split and refract, so that it looks like any moving object is followed by its own ghost. Reygadas has suggested the intent was to make the images look as they might if you were watching them through an old windowpane, and I can definitely see what he's getting at there.

But it doesn't take something as specific as that image to understand what the images are attempting to convey: a certain separation from the material born of nostalgia (the film acts as a slantwise autobiography, but I think that any attempt to chase it down that way is doomed to severely misrepresenting what the film is), and mired in a perspective that doesn't quite understand what's going on literally, nor in a strictly chronological fashion, but is certainly capable of following along with the ebb and flow of mood. The movie opens with a barnburner of a shot in which a little girl, Rut (Rut Reygadas, the director's child) is hastening around a rural yard, chatting enthusiastically with the animals around her, as the sky grows positively apocalypstic in its overcast gloom, and the shot is incredibly anxious for us to occupy the perspective of a very small child, looking right at her (or even up a tiny bit), and to spend a good long time wrapped up in her headspace. Is Post Tenebras Lux meant to be understood as a film from a child's perspective, with its ellipses standing in for the ways that a child fails to understand everything that happens around her? It's hard to say - that's certainly one of many readings available to us.

But even asking the question assumes that there's a way to "solve" Post Tenebras Lux, and one of the things that I think we need to accept about the film is that there simply isn't such a thing as a "solution". This is a movie of impressions and attitudes; it is an emphatically and specifically religious film as well, in which the Devil or something like it is an active figure, personal failures are specifically considered to be sins, in an acutely spiritual (though not specifically Catholic) sense, and an evocative sense of mysticism is laid over the film's very best moments, including the plunge into flickering blackness that follows Rut's merry run around the yard. I think it's absolutely fair to say, in fact, that the biggest problem with Post Tenebras Lux is that it spends far too much time outside of the explicitly spiritual and mystical register established in its opening 20 minutes, with the most literal interpretation of the title, and a utterly breathtaking scene of the Devil, a featureless red space in human form, deliberately stalking through a family's home.

The film actually spends most of its time in a wholly different mode, functioning variably as a study of one family: Juan (Adolfo Jiménez Castro), Natalia (Nathalia Acevedo), and their children, Rut and Eleazar (Eleazar Reygadas), with frequent layovers in scenes that don't have anything to do with any of them. At its worse, the film basically retreads the aesthetic of Silent Light, letting the domestic drama play out in mercilessly long, still moments where the camera soaks up action in something that we might call a naturalistic mode if there was anything even marginally naturalistic about the staging or performances in the film. At its best, it is a phenomenally effective tone poem about good and evil, though I think it should be said that Reygadas's apparent definition of "evil" is more reactionary and unforgiving than mine is; in addition to the film's almost melodramatic fear of sex, there's a repeated motif about addiction and recovery that suggests that human weakness is evil, or at least symptomatic of it, which is a bit harsher and less forgiving than I care for my spiritual allegories to be (I'd contrast the film to The Tree of Life, just about the only thematic mate I can think of in recent cinema, where human weakness is treated with love and understanding and overcome with joy, not with moralising).

That's nitpicking though, and of a particularly weird sort. Frankly, being in a position where I feel like I'm debating religion with a filmmaker because of his movie is so exciting that I don't know what to do with it, and that's enough to make Post Tenebras Lux a completely essential piece of film art. Talking about it in terms of artistic effectiveness is simply bizarre, because the film is far enough away from anything covered by rules that it can't rightly be said to break them or not; I wish mightily that middle was as good as the opening 20 minutes and the beautifully out-of-nowhere but thematically ripe final scene, but that's sort of immaterial. Post Tenebras Lux is an experiment in expressing a religious feeling through cinema, and though the experiment could have been more successful, who else would think to make it? It's not enough to clearly mark Reygadas as one of our best filmmakers in the world right now, but he's easily one of the most essential, and I can think of no reason not to assume that's just as good

[X]/10, though if you made me put a number on it, that number would probably be 8