Alexandre the great

A third review requested by Zev Burrows, with thanks for his multiple contributions to the ACS Fundraiser.

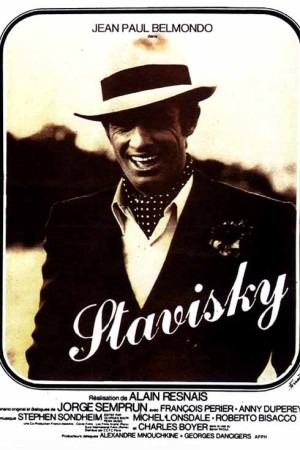

To date, the 1974 film Stavisky... is the only straight filmed treatment of one of the key events in interwar French history (the 1937 Hollywood film Stolen Holiday is a fanciful and mostly fictionalised interpretation), but that's not the only historically intriguing position the film occupies. It's also something of a cross-section of French film across the decades: the cast includes three generations of iconic French leading men, if inadvertently. Jean-Paul Belmondo plays the title character, while Charles Boyer has one of the meatier supporting roles as an older patron, and the very young Gérard Depardieu appears in one scene, just three years into his career. Of course, nobody could have imagined that Depardieu would eventually have an international fame every bit as great as his older co-stars', but the mere fact of it gives Stavisky... a neat little capsule feeling of past, present, and future. So too does the mixed aesthetic of a 1930s-set biopic with distinctly '70s cinematography, make-up and costumes doing all they can to evoke the past, and a score nimbly blurring the 40 years separating the story from its production. And certainly not least, Stavisky... is more or less the dividing line in the career of the great director Alain Resnais, whose work in the '50s and '60s as one of the great figures of French cinema during the Nouvelle Vague (a movement he did not consider himself a member of) was fired up with aesthetic and political radicalism. He'd not made a feature in six years prior to Stavisky..., and it mostly established the template he'd ride out for much of the rest of his life, using a much more subdued version of the same explosive aesthetics, hidden inside what a casual observer might mistakenly dismiss as "prestige" cinema, in pursuit of his beloved theme of memory and nostalgia as unreliable traps.

Stavisky... is hardly stripped bare of politics: the opening sequence concerns Leon Trotsky's (Yves Peneau) arrival as an exile to France late in 1933, and the real-life events of the main plot were the lead-up to a right-wing riot that lead to the leftist French government relinquishing power (this is not seen too much onscreen). The aesthetics are quite a bit cagier in their radicalism: to look at it, Stavisky... seems for all the world like a tony slice of awards baiting cinema, and it's only as you really start to settle into the film's rhythm that it starts to be clear that the movie is off, somehow. For starters, by not actually having any rhythm to settle into. It's hard to explain how Stavisky... is paced and assembled - not as a history lesson, that's for damn sure. I do not know how well-known the Stavisky Affair was in France in 1974, but Jorge Semprún's screenplay (or, at least, Resnais's direction thereof; the project preceded Resnais's involvement, but it aligns so much with his interests that I have to assume it was tinkered with) is not heavily invested in needless exposition. Or even, arguably, needed exposition. For well over half of its running time, Stavisky... barely even has a narrative, instead focusing on scenes of Serge Alexandre Stavisky (Belmondo, for whom this was a passion project) more or less floating through 1933 France as an irrepressible con-man and raconteur and head-over-heels lover of the theater. He wastes enormous sums of money on quixotic artistic and gambling impulses and makes even more enormous sums fencing jewels and passing counterfeit bonds. He has friends and colleagues among the elite, and he's chased by the dogged Inspector Bonny (Claude Rich), and... and...

Stavisky... - the ellipses start to make sense at this point - is massively interested in delaying the answer to that "and?" It is a film about a man whose entire life is dissembling, and whose historical importance owes mostly to the impression of scandal surrounding him because of that dissembling, and to explore that idea, the film itself dissembles. We don't get a square answer from Stavisky... for ages and ages, and when we do, the answer is "nobody knows the answers". The fragmentary nature of the plot, moving through scenes that are contained within themselves but not clearly linked together, turns out to have a possibly explanation: we're watching the recollections of the people who knew Alexandre, weeks or months after the fact, giving testimony to the police. Explicitly, the people offering that testimony have no clear sense of who he was or what motivated him, and that stretches backward to reveal that all we thought we were learning about the man was, in fact, just impressions and suggestions.

That's a bold and sassy approach to take, offering the viewer clarity in the form of the claim "so everything you've been watching is, in fact, ambiguous", and it pure Resnais. I think it would take a great deal of stretching to call this one of the director's masterpieces; even in his more audience-friendly post-'60s mode, he had the heights of Mon oncle d'Amérique in front of him still. The French critics who accused Stavisky... of being a little too much of a crowd-pleaser to engage with the political context it was so eagerly weaving into the borders weren't "wrong", though the film has already attempted to inoculate itself against that criticism in the opening title card: "les auteurs n'ont pas cherché à faire œuvre d'historiens" ("the authors do not seek to do the work of historians"). Stavisky... is not a political history; it is, arguably, a cultural one, with Alexandre Stavisky filling the role of the aspirational bourgeois right at the point that Europe started passing the point that World War II was assured. His fascination with theatricality - apparently Resnais's chief interest in the character - is an extension of his willingness to lie and fake and put on a show for the world to admire him and give him what he wants: if he has an inner self, nobody including the filmmakers knows what it is (including Belmondo, who brilliantly plays charisma as a concept rather than a charismatic man, only giving Alexandre a personality in his scenes alone with his wife, played by Anny Duperey). He is a hollow man, and it is his kind of hollowness that created the circumstances of pre-War Europe's descent into a terrifying lack of ideological commitment. If the film fails to place that in explicitly left-wing terms (and to be fair, the Trotsky material is certainly oddly underexplored and maybe not to the film's absolute benefit), that's because it's fonder of implication than statement, and this is true in all ways.

Anyway, for all the brilliant slipperiness of the structure, it is a crowd-pleaser, the disappointed critics had that right. It's gorgeous: shot by Sacha Vierny with the ungainly graininess familiar from most '70s cinema, but using that in the film's favor to give it a patina of age. It looks as fuzzy as it feels, like an unrestored painting by a forgotten master - and certainly, there's mastery in the lighting, which bathes the exteriors especially in a faux-nostalgia that is on the one hand appealing and on the other hand plays up the same sense of artifice that all the scenes leaning on the main character's theatrical interests do. Nothing else in the film's technique is quite as extraordinarily useful to its argument as the cinematography, though I'd be much remiss in failing to mention that this was the first feature film with a score composed by musical theater legend Stephen Sondheim (out of a grand total of two). And it's a pretty great score, at times, though he sometimes relies a bit too heavily on pastiches of '30s music in a way that feels less than inspired. Mostly, though, the score synthesises those pastiches with more forcibly tuneless, contemporary-feeling music that pulls Stavisky... out of time and gives it a sense of brittle modernity which helps situate it in a more intellectual place than the costume drama trappings suggest. That being said, the best thing about having Sondheim come aboard was that it meant his reliable collaborator Jonathan Tunick came along as well to do the orchestrations, and they are amazing: there's a moment in which an oboe loudly cuts into a somewhat routine "this is tense" musical passage in a way that gave me an honest-to-God jolt.

It's only in a career as impressive as Resnais's that Stavisky... can be honestly referred to as "minor"; the ideas are not terribly unique, though they've been worked out in an extremely satisfying way. Belmondo is beyond superb, and so, for that matter, is Boyer, as a prim old conservative who is fascinated by and then made ever so slightly sad by his new mysterious friend - I'd be tempted to consider the best work either of them ever did, though I really had ought to see more of Boyer's work in his native French before I start making that kind of huge claim. It's a thoughtful critique of reflexive capitalism disguised as a puzzle box hiding inside a fussy costume drama; quite a pleasure it it is to unpack, and more of a pleasure when there's something genuinely worthwhile inside of it all. If it's quite overshadowed by the masterpieces surrounding it on both sides, it's still quite a nifty successful experiment on its own terms.

To date, the 1974 film Stavisky... is the only straight filmed treatment of one of the key events in interwar French history (the 1937 Hollywood film Stolen Holiday is a fanciful and mostly fictionalised interpretation), but that's not the only historically intriguing position the film occupies. It's also something of a cross-section of French film across the decades: the cast includes three generations of iconic French leading men, if inadvertently. Jean-Paul Belmondo plays the title character, while Charles Boyer has one of the meatier supporting roles as an older patron, and the very young Gérard Depardieu appears in one scene, just three years into his career. Of course, nobody could have imagined that Depardieu would eventually have an international fame every bit as great as his older co-stars', but the mere fact of it gives Stavisky... a neat little capsule feeling of past, present, and future. So too does the mixed aesthetic of a 1930s-set biopic with distinctly '70s cinematography, make-up and costumes doing all they can to evoke the past, and a score nimbly blurring the 40 years separating the story from its production. And certainly not least, Stavisky... is more or less the dividing line in the career of the great director Alain Resnais, whose work in the '50s and '60s as one of the great figures of French cinema during the Nouvelle Vague (a movement he did not consider himself a member of) was fired up with aesthetic and political radicalism. He'd not made a feature in six years prior to Stavisky..., and it mostly established the template he'd ride out for much of the rest of his life, using a much more subdued version of the same explosive aesthetics, hidden inside what a casual observer might mistakenly dismiss as "prestige" cinema, in pursuit of his beloved theme of memory and nostalgia as unreliable traps.

Stavisky... is hardly stripped bare of politics: the opening sequence concerns Leon Trotsky's (Yves Peneau) arrival as an exile to France late in 1933, and the real-life events of the main plot were the lead-up to a right-wing riot that lead to the leftist French government relinquishing power (this is not seen too much onscreen). The aesthetics are quite a bit cagier in their radicalism: to look at it, Stavisky... seems for all the world like a tony slice of awards baiting cinema, and it's only as you really start to settle into the film's rhythm that it starts to be clear that the movie is off, somehow. For starters, by not actually having any rhythm to settle into. It's hard to explain how Stavisky... is paced and assembled - not as a history lesson, that's for damn sure. I do not know how well-known the Stavisky Affair was in France in 1974, but Jorge Semprún's screenplay (or, at least, Resnais's direction thereof; the project preceded Resnais's involvement, but it aligns so much with his interests that I have to assume it was tinkered with) is not heavily invested in needless exposition. Or even, arguably, needed exposition. For well over half of its running time, Stavisky... barely even has a narrative, instead focusing on scenes of Serge Alexandre Stavisky (Belmondo, for whom this was a passion project) more or less floating through 1933 France as an irrepressible con-man and raconteur and head-over-heels lover of the theater. He wastes enormous sums of money on quixotic artistic and gambling impulses and makes even more enormous sums fencing jewels and passing counterfeit bonds. He has friends and colleagues among the elite, and he's chased by the dogged Inspector Bonny (Claude Rich), and... and...

Stavisky... - the ellipses start to make sense at this point - is massively interested in delaying the answer to that "and?" It is a film about a man whose entire life is dissembling, and whose historical importance owes mostly to the impression of scandal surrounding him because of that dissembling, and to explore that idea, the film itself dissembles. We don't get a square answer from Stavisky... for ages and ages, and when we do, the answer is "nobody knows the answers". The fragmentary nature of the plot, moving through scenes that are contained within themselves but not clearly linked together, turns out to have a possibly explanation: we're watching the recollections of the people who knew Alexandre, weeks or months after the fact, giving testimony to the police. Explicitly, the people offering that testimony have no clear sense of who he was or what motivated him, and that stretches backward to reveal that all we thought we were learning about the man was, in fact, just impressions and suggestions.

That's a bold and sassy approach to take, offering the viewer clarity in the form of the claim "so everything you've been watching is, in fact, ambiguous", and it pure Resnais. I think it would take a great deal of stretching to call this one of the director's masterpieces; even in his more audience-friendly post-'60s mode, he had the heights of Mon oncle d'Amérique in front of him still. The French critics who accused Stavisky... of being a little too much of a crowd-pleaser to engage with the political context it was so eagerly weaving into the borders weren't "wrong", though the film has already attempted to inoculate itself against that criticism in the opening title card: "les auteurs n'ont pas cherché à faire œuvre d'historiens" ("the authors do not seek to do the work of historians"). Stavisky... is not a political history; it is, arguably, a cultural one, with Alexandre Stavisky filling the role of the aspirational bourgeois right at the point that Europe started passing the point that World War II was assured. His fascination with theatricality - apparently Resnais's chief interest in the character - is an extension of his willingness to lie and fake and put on a show for the world to admire him and give him what he wants: if he has an inner self, nobody including the filmmakers knows what it is (including Belmondo, who brilliantly plays charisma as a concept rather than a charismatic man, only giving Alexandre a personality in his scenes alone with his wife, played by Anny Duperey). He is a hollow man, and it is his kind of hollowness that created the circumstances of pre-War Europe's descent into a terrifying lack of ideological commitment. If the film fails to place that in explicitly left-wing terms (and to be fair, the Trotsky material is certainly oddly underexplored and maybe not to the film's absolute benefit), that's because it's fonder of implication than statement, and this is true in all ways.

Anyway, for all the brilliant slipperiness of the structure, it is a crowd-pleaser, the disappointed critics had that right. It's gorgeous: shot by Sacha Vierny with the ungainly graininess familiar from most '70s cinema, but using that in the film's favor to give it a patina of age. It looks as fuzzy as it feels, like an unrestored painting by a forgotten master - and certainly, there's mastery in the lighting, which bathes the exteriors especially in a faux-nostalgia that is on the one hand appealing and on the other hand plays up the same sense of artifice that all the scenes leaning on the main character's theatrical interests do. Nothing else in the film's technique is quite as extraordinarily useful to its argument as the cinematography, though I'd be much remiss in failing to mention that this was the first feature film with a score composed by musical theater legend Stephen Sondheim (out of a grand total of two). And it's a pretty great score, at times, though he sometimes relies a bit too heavily on pastiches of '30s music in a way that feels less than inspired. Mostly, though, the score synthesises those pastiches with more forcibly tuneless, contemporary-feeling music that pulls Stavisky... out of time and gives it a sense of brittle modernity which helps situate it in a more intellectual place than the costume drama trappings suggest. That being said, the best thing about having Sondheim come aboard was that it meant his reliable collaborator Jonathan Tunick came along as well to do the orchestrations, and they are amazing: there's a moment in which an oboe loudly cuts into a somewhat routine "this is tense" musical passage in a way that gave me an honest-to-God jolt.

It's only in a career as impressive as Resnais's that Stavisky... can be honestly referred to as "minor"; the ideas are not terribly unique, though they've been worked out in an extremely satisfying way. Belmondo is beyond superb, and so, for that matter, is Boyer, as a prim old conservative who is fascinated by and then made ever so slightly sad by his new mysterious friend - I'd be tempted to consider the best work either of them ever did, though I really had ought to see more of Boyer's work in his native French before I start making that kind of huge claim. It's a thoughtful critique of reflexive capitalism disguised as a puzzle box hiding inside a fussy costume drama; quite a pleasure it it is to unpack, and more of a pleasure when there's something genuinely worthwhile inside of it all. If it's quite overshadowed by the masterpieces surrounding it on both sides, it's still quite a nifty successful experiment on its own terms.

Categories: crime pictures, french cinema, fun with structure, the dread biopic