Nothing more foolish than a man chasin' his hat

Miller's Crossing may or may not be the Coen brother's "best" movie. I think that argument exists to be made, but it's hard to get all the way through it with Barton Fink and Fargo over there in the corner, flexing their muscles. It is, though, almost certainly their most elaborate and dense movie, both as a narrative and a character study - I have found it uniformly necessary to see Coen movies twice to fully suss out everything they have going on in terms of mood, symbol, and theme, but Miller's Crossing is unique in that it took me two tries just to understand what was happening in the story. There is and has always been a subset of critics that view this complexity as a blind, disguising what is ultimately just a particularly elegant genre riff without much meat on its bones, and that's not a completely baseless accusation; certainly one of the reasons that the film is extra-hard to parse is entirely a function of how much of a genre film it is. It's something of a mash-up of Prohibition-era storytelling with '80s American indie filmmaking (though this film, the Coens' third, was their most studio-bound to that point), and the most obvious element of a very idiosyncratic screenplay is a exuberant passion for '20s slang used in a way that's not exactly period-correct, but is also much too brittle and artificial for it to come across as in any way timeless or fresh, no more in the 2010s than at its debut in 1990.

The most useful way to think of it, in my estimation, is not as a faithful recreation of a vintage gangster picture, nor as a faithful (and uncredited) adaptation of Dashiell Hammett's 1929 novel Red Harvest and 1930's The Glass Key - it's not really "faithful" in either of those capacities - but as something like a performance piece based on those ideas. It is a wildly artificial, mediated thing: nobody has every talked or acted like this in reality, nor even in any other movie. Perhaps the right way to describe it is as pageantry, an act of recreating the idea of a gangster story in a way that calls maximum attention to the artifice of it; other Coen films function in a similar way, as heavily abstracted ideas of a genre film rather than an actual version of a genre film (especially early on - The Hudsucker Proxy, from 1994, is the other clearest example of this tendency), but Miller's Crossing is probably the film where this trick pays the most dividends. It is to a great degree a film about performance, for its central character is a man whose entirely personality is mostly a matter of what he chooses to show to other people, and the somewhat arch brittleness of the whole exercise is a good context for that character to exist in.

That's another point of distinction: Miller's Crossing was the first Coen film that was primarily a character study, though like everything else about the film, it's not immediately apparent that this is the case. But what else do you call a movie in which every scene but one is told from the perspective of one man, Tom Reagan (Gabriel Byrne, in what is by miles and miles the best performance I've ever seen of his), and whose final shot openly invites us to apply what we've learned about him to a stunningly enigmatic expression on his face? It's a character study through and through, and that's not even the weird part; it's also a love story in which this same man devotes all his energy to protecting, destroying, and redeeming the only human being for whom he feels any demonstrated kind feeling. But we'll get there in a minute.

Miller's Crossing is, at its simplest, a Red Harvest-esque tale of a gang war, in which the vivacious Irish mobster Leo O'Bannon (Albert Finney) decides against the strenuous suggestions of Tom, his closest adviser and seeming best friend, not to let the Italian gangleader Johnny Caspar (Jon Polito) kill a chiseling Jewish bookie, Bernie Bernbaum (John Turturro). This is in part because Leo doesn't want to let the uppity Caspar get his way; it's also because Bernie's sister Verna (Marcia Gay Harden), a noted piece of Bad News, is currently sleeping with Leo, and making him awfully happy. Once Tom fails to keep things from escalating, he splits with Leo and joins up with Caspar, apparently in the hope of entrenching himself high up in the trust of the city's new mob boss, but it's immediately clear that whatever game Tom's playing, Caspar's success and well-being are of only incidental concern.

There's so much going on in the script, in the performances, and in the aesthetic that it's almost impossible to synthesise it all into one simple reading, so I won't pretend that any of what I'm about to say is definitive, but to me, Miller's Crossing is above all about Tom's love for Leo, which doesn't necessarily have a homoerotic tint to it at all, though that's certainly a common enough reading among academic critics. Certainly, Miller's Crossing is unusually concerned with homosexuality, with three men identified as being involved in a destructive love triangle - the centrally problematic Bernie among them - and the word "queer" appearing in the dialogue far too often for it to simply be for period color. After all, while "queer" simply meant "odd and dysfunctional" in the '30s, by 1990 it had definitively transitioned into a synonym for "not-heterosexual nor traditionall-gendered". If the word was merely peppered in for flavor, like plenty of other archaisms, there'd be no point in digging in further, but "queer" is used a lot in Miller's Crossing; it is easily the most common obsolete slang term in dialogue. And with the obvious foregrounding of the gay supporting characters (which could simply be seen as literalising the coded homosexuals in movies like The Maltese Falcon or The Big Combo) in concert, it's really hard to doubt that the Coens meant for the audience to have gayness much on their mind in watching Miller's Crossing.

None of which proves, or even implies, that Tom is lusting after Leo, or that his affair with Verna is sublimating his desire to sleep with Leo, though that's a fine and durable reading. What it does absolutely demand is that we look at the film and see in it a muddying of gender constructs, and this is certainly something that we can see in Tom, right there on the surface. Compared to the usual gangster picture or film noir hero, he's not very "masculine": one of his defining traits is a tendency to be badly beaten in any physical altercation, even those with old men and women, not least because he typically doesn't even move to defend himself. He's a spectacularly incongruous figure in the hard-boiled surroundings, with people spouting out florid lines of dialogue that verge on self-parody, and multiple people dying in wide-eyed, unblinking machine gun barrages. He's passive, thoughtful (the only character who both thinks clearly and comes to the right conclusions), soft-spoken, and turned off by violence, none of them "tough guy movie hero" tropes, and certainly none of them shared by the other straight men in the movie. Even Verna (the only prominent women) and two of the three gay men act in more traditionally-male ways than Tom does.

This leaves him a dislocated protagonist, genderless and sensitive and physically weak in a genre that is one of the most quintessential masculine in the history of American film - doubly so if we allow that this is as much a noir pastiche as a gangster film pastiche. It is a universe which Tom can manipulate more easily than any other character, filling the role of a seer or wiseman or god among the rest of the cast (the much-repeated phrase "Jesus, Tom" is irresistible in suggesting that he is in but not of the world he walks in); but it is also a universe where he doesn't fit and isn't happy. Leo is a protective figure and focus of Tom's kindly feelings - prospective lover, prospective father, prospective friend, it's largely immaterial. Leo is the thing that enables Tom to function well in this environment, and he repays Leo with all of his love. The tragedy of the thing - and it depends a lot on how one reads the hugely ambiguous final scene, but it fits my interpretation - is that by fully giving himself over to Leo, Tom enables the exact unconscious betrayal by Leo that leaves him without a home or meaning in the end.

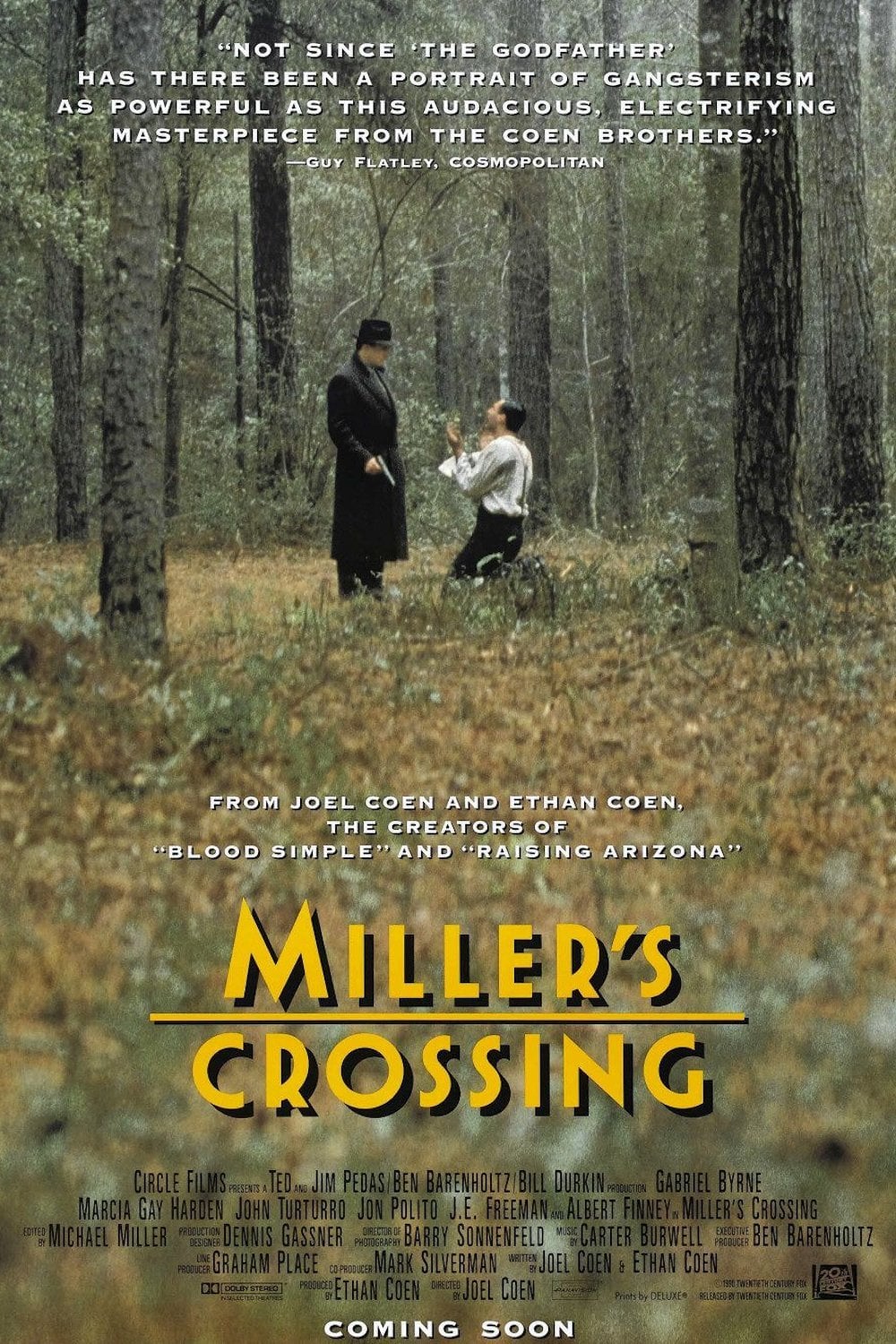

It's a sign of how much Miller's Crossing has going on that I can have wandered about for that many words and said so little about so much of it. Not even a word about the exquisite craftsmanship! That includes an absolutely perfect opening scene that rivals only the mini-movie at the start of Raising Arizona as my favorite sequence in the Coen filmography, a perfectly-timed tour of Polito's sweaty anxiety and Finney's blunt authority (both men are terrific throughout the film, but at their best in this scene), introducing Tom slowly and methodically; the sound design guiding our attention with laser precision; the dialogue warming up the film's strange vocabulary, plunging us into it but not without a guidemap; the driving editing by the film's namesake, Michael R. Miller (I believe this was the last Coen film that the brothers did not edit themselves). The Carter Burwell score is hands-down my favorite of his many glorious Coen soundtracks, drawing from Irish folk music, traditional Hollywood, and Italian influences to tell the entire emotional story in a way that you can follow without any other cues. And Barry Sonnenfeld's luminous cinematography is both beautiful and psychologically flawless, depicting the claustrophobic city with menacing but chiaroscuro-free shadows, and reaching masterpiece-level work in the nightmare setting of the eponymous woods, a hazy place of flatness and danger that deliberately quotes The Conformist without in any way copying it. It was his second to last project as director of photography, before jumping into the director's chair; and as much as I love some of his movies (and despise others) Miller's Crossing is all the evidence we need to know what a fantastic alternate career was cut short.

It is, if I may crudely try to wrap things up, the most thoroughly inexhaustible movie the Coens have ever made. It says less about humanity than Fargo, explores the boundaries of cinema less than Barton Fink, and is less altogether flawless than No Country for Old Men, but I'd reach for it ahead of any of them. It is complex and deep and slow to reveal its secrets, but I have consistently been thrilled to do the work necessary to pull them out, and am wholly content to call this my favorite, if that has any value, among all the Coens' films.

The most useful way to think of it, in my estimation, is not as a faithful recreation of a vintage gangster picture, nor as a faithful (and uncredited) adaptation of Dashiell Hammett's 1929 novel Red Harvest and 1930's The Glass Key - it's not really "faithful" in either of those capacities - but as something like a performance piece based on those ideas. It is a wildly artificial, mediated thing: nobody has every talked or acted like this in reality, nor even in any other movie. Perhaps the right way to describe it is as pageantry, an act of recreating the idea of a gangster story in a way that calls maximum attention to the artifice of it; other Coen films function in a similar way, as heavily abstracted ideas of a genre film rather than an actual version of a genre film (especially early on - The Hudsucker Proxy, from 1994, is the other clearest example of this tendency), but Miller's Crossing is probably the film where this trick pays the most dividends. It is to a great degree a film about performance, for its central character is a man whose entirely personality is mostly a matter of what he chooses to show to other people, and the somewhat arch brittleness of the whole exercise is a good context for that character to exist in.

That's another point of distinction: Miller's Crossing was the first Coen film that was primarily a character study, though like everything else about the film, it's not immediately apparent that this is the case. But what else do you call a movie in which every scene but one is told from the perspective of one man, Tom Reagan (Gabriel Byrne, in what is by miles and miles the best performance I've ever seen of his), and whose final shot openly invites us to apply what we've learned about him to a stunningly enigmatic expression on his face? It's a character study through and through, and that's not even the weird part; it's also a love story in which this same man devotes all his energy to protecting, destroying, and redeeming the only human being for whom he feels any demonstrated kind feeling. But we'll get there in a minute.

Miller's Crossing is, at its simplest, a Red Harvest-esque tale of a gang war, in which the vivacious Irish mobster Leo O'Bannon (Albert Finney) decides against the strenuous suggestions of Tom, his closest adviser and seeming best friend, not to let the Italian gangleader Johnny Caspar (Jon Polito) kill a chiseling Jewish bookie, Bernie Bernbaum (John Turturro). This is in part because Leo doesn't want to let the uppity Caspar get his way; it's also because Bernie's sister Verna (Marcia Gay Harden), a noted piece of Bad News, is currently sleeping with Leo, and making him awfully happy. Once Tom fails to keep things from escalating, he splits with Leo and joins up with Caspar, apparently in the hope of entrenching himself high up in the trust of the city's new mob boss, but it's immediately clear that whatever game Tom's playing, Caspar's success and well-being are of only incidental concern.

There's so much going on in the script, in the performances, and in the aesthetic that it's almost impossible to synthesise it all into one simple reading, so I won't pretend that any of what I'm about to say is definitive, but to me, Miller's Crossing is above all about Tom's love for Leo, which doesn't necessarily have a homoerotic tint to it at all, though that's certainly a common enough reading among academic critics. Certainly, Miller's Crossing is unusually concerned with homosexuality, with three men identified as being involved in a destructive love triangle - the centrally problematic Bernie among them - and the word "queer" appearing in the dialogue far too often for it to simply be for period color. After all, while "queer" simply meant "odd and dysfunctional" in the '30s, by 1990 it had definitively transitioned into a synonym for "not-heterosexual nor traditionall-gendered". If the word was merely peppered in for flavor, like plenty of other archaisms, there'd be no point in digging in further, but "queer" is used a lot in Miller's Crossing; it is easily the most common obsolete slang term in dialogue. And with the obvious foregrounding of the gay supporting characters (which could simply be seen as literalising the coded homosexuals in movies like The Maltese Falcon or The Big Combo) in concert, it's really hard to doubt that the Coens meant for the audience to have gayness much on their mind in watching Miller's Crossing.

None of which proves, or even implies, that Tom is lusting after Leo, or that his affair with Verna is sublimating his desire to sleep with Leo, though that's a fine and durable reading. What it does absolutely demand is that we look at the film and see in it a muddying of gender constructs, and this is certainly something that we can see in Tom, right there on the surface. Compared to the usual gangster picture or film noir hero, he's not very "masculine": one of his defining traits is a tendency to be badly beaten in any physical altercation, even those with old men and women, not least because he typically doesn't even move to defend himself. He's a spectacularly incongruous figure in the hard-boiled surroundings, with people spouting out florid lines of dialogue that verge on self-parody, and multiple people dying in wide-eyed, unblinking machine gun barrages. He's passive, thoughtful (the only character who both thinks clearly and comes to the right conclusions), soft-spoken, and turned off by violence, none of them "tough guy movie hero" tropes, and certainly none of them shared by the other straight men in the movie. Even Verna (the only prominent women) and two of the three gay men act in more traditionally-male ways than Tom does.

This leaves him a dislocated protagonist, genderless and sensitive and physically weak in a genre that is one of the most quintessential masculine in the history of American film - doubly so if we allow that this is as much a noir pastiche as a gangster film pastiche. It is a universe which Tom can manipulate more easily than any other character, filling the role of a seer or wiseman or god among the rest of the cast (the much-repeated phrase "Jesus, Tom" is irresistible in suggesting that he is in but not of the world he walks in); but it is also a universe where he doesn't fit and isn't happy. Leo is a protective figure and focus of Tom's kindly feelings - prospective lover, prospective father, prospective friend, it's largely immaterial. Leo is the thing that enables Tom to function well in this environment, and he repays Leo with all of his love. The tragedy of the thing - and it depends a lot on how one reads the hugely ambiguous final scene, but it fits my interpretation - is that by fully giving himself over to Leo, Tom enables the exact unconscious betrayal by Leo that leaves him without a home or meaning in the end.

It's a sign of how much Miller's Crossing has going on that I can have wandered about for that many words and said so little about so much of it. Not even a word about the exquisite craftsmanship! That includes an absolutely perfect opening scene that rivals only the mini-movie at the start of Raising Arizona as my favorite sequence in the Coen filmography, a perfectly-timed tour of Polito's sweaty anxiety and Finney's blunt authority (both men are terrific throughout the film, but at their best in this scene), introducing Tom slowly and methodically; the sound design guiding our attention with laser precision; the dialogue warming up the film's strange vocabulary, plunging us into it but not without a guidemap; the driving editing by the film's namesake, Michael R. Miller (I believe this was the last Coen film that the brothers did not edit themselves). The Carter Burwell score is hands-down my favorite of his many glorious Coen soundtracks, drawing from Irish folk music, traditional Hollywood, and Italian influences to tell the entire emotional story in a way that you can follow without any other cues. And Barry Sonnenfeld's luminous cinematography is both beautiful and psychologically flawless, depicting the claustrophobic city with menacing but chiaroscuro-free shadows, and reaching masterpiece-level work in the nightmare setting of the eponymous woods, a hazy place of flatness and danger that deliberately quotes The Conformist without in any way copying it. It was his second to last project as director of photography, before jumping into the director's chair; and as much as I love some of his movies (and despise others) Miller's Crossing is all the evidence we need to know what a fantastic alternate career was cut short.

It is, if I may crudely try to wrap things up, the most thoroughly inexhaustible movie the Coens have ever made. It says less about humanity than Fargo, explores the boundaries of cinema less than Barton Fink, and is less altogether flawless than No Country for Old Men, but I'd reach for it ahead of any of them. It is complex and deep and slow to reveal its secrets, but I have consistently been thrilled to do the work necessary to pull them out, and am wholly content to call this my favorite, if that has any value, among all the Coens' films.