Faith is a fact. No, a facet. I almost said "faith is a fact"

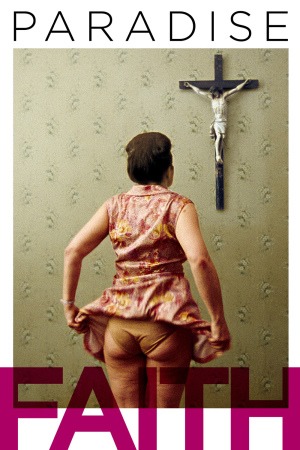

Paradise: Faith proves me right about one thing, anyway: Ulrich Seidl's Paradise trilogy would have been better suited to being the Paradise anthology film. The first part, Paradise: Love, is a fine two hour movie that would have lost nothing and maybe gained some focus as a 40-minute sequence; Faith, meanwhile, is a two-hour movie that is actively trying. A 40-minute version of this scenario would have been weaker, I am sure, than either a 40-minute or a 112-minute Love, but it would certainly not have been as redundant, stretched-out, and airless as the version of Faith that Seidl signed off on.

The film comes from an intolerably smug and cynical place - I am by no means a cheerleader for strong religious conviction and even less for evangelical Christianity, but the character Seidl and co-writer Veronika Franz have whipped up to anchor their ironic tale (though not as caustic in its ironies as Love) feels very much like an intensely, self-destructively religious woman as conceived by somebody who flat-out doesn't understand what faith consists of for the faithful. Anna Maria (Maria Hoffstätter) isn't a person, but a cartoon; and while Margarete Tiesel's Teresa in Love (Anna Maria's sister, a fact not even cryptically alluded to in Faith) is herself more of a conceptual construct than a recognisable human in some ways, the structure of that film's story and Tiesel's performance in it both help to make the film an exploration of her psychology in ways that feel at least plausible and grounded. Nothing of the sort for poor Anna Maria, whose obsession with sexual sinfulness results in scenes of her stripping naked and scourging herself, backing away from a far-too-convenient orgy in a park while fondling her rosary lustily, or rubbing her nether regions with a giant crucifix under the covers, in a scene that is meant to be a provocation, and comes off as a shrilly literal one that is far too silly and overwrought to offend or disturb anybody. It's paint-by-numbers "crazy sexually repressed religious hypocrite" writing that Hoffstätter is quite undone by; no actress could make a plausible character out of this being, and she ends up playing to the caricatured elements rather than modulating them with anything marginally human.

Insofar as Faith has a plot, it is this: some years ago, Anna Maria's husband, an Egyptian Muslim named Nabil (Nabil Saleh), disappeared. Now he has returned, a paraplegic - though it's left pointedly vague whether he was paraplegic before, and why he left, and whose decision that was. His return significantly upsets Anna Maria's plans for summer holiday, which include taking part in a prayer group enthusiastically planning to restore Catholicism to Austria, and marching door-to-door to do missioning work, aided by a foot-tall statue of the Virgin Mary that she positions in people's homes to make them worship with her. Having a man back in the house - a man who keeps bringing up sex, either in terms of desire or in terms of his inability to have it thanks to his condition - does absolutely no good to Anna Maria's successful attempts to eroticise Jesus, and the imbalance that Nabil's presence brings pretty quickly turns to violent lashing out on both sides, and unmistakably pan-denominational terrible behavior, and a vivid demonstration of just how truly good this hyper-devout woman actually is.

It is tediously programmatic, and it is horribly redundant; there aren't all that many points to be made and all of them are made in the first and last half-hours, which leads a huge chunk of movie devoted only to reiterating and repeating things we've already seen, and finding new ways to make Anna Maria's sexual repression creepier and more appalling. It is, altogether, the movie that Love kept threatening to be, and always managed to dodge away from: an unmitigated exercise in nastiness for the sake of nastiness, hysterical Austrian cinema of cruelty in which the main character is subjected to viciousness from herself and others that demonstrates to the audience nothing except our own capacity for watching self-flagellation before we grow bored of it. Whereas Love had some reasonably interesting things to say about social codes and self-definition (and also some very tired things to say about relations between Europe and Africa), Faith is delighted to traffic heavily in clichés both narrative and aesthetic, with its very samey feeling intensified rather than disguised by the savagery of what's being depicted onscreen.

There's one exception to all of this, and that's Anna Maria's missioning. Thrice in the movie, she ends up some poor victim's house to preach her deprivation-besotted version of Catholicism to them, and these shaggy scenes are by far the liveliest and most interesting scenes in the film, the only places where it feels like humans are involved and not blank spots on Seidl's Euroart Mad Libs. This despite feeling somewhat like improvisational acting exercises, where Hofstätter and the people she's acting against have each been given a single goal and told to spend five minutes chasing it without variation; but the way that these scenes spill out and go on past the point of reason (particularly the third, when Anna Maria struggles to give advice to a belligerent drunk) is, itself, fairly energetic and captivating, sort of like watching high-wire artists. There's always a sense that something will have to give, and it never does, and this ends up giving a much clearer insight into who Anna Maria is and why we might possibly want to study her more closely than all the self-abuse in the rest of the film could ever do.

Outside of those scenes, making up far too little of the overall running time, Faith is a whole lot of nothing: perfectly generic frames that stand still for very long in the fashion of glacial European art films, as a woman raves and raves and never gives us any insight into anything. If this is meant to give us some understanding about humanity, it fails on the level of lacking any humans; it its meant to shock us in our complacency, it fails on the level of being abysmally boring. This is the most rote, obnoxious kind of "fuck you, audience" filmmaking, as unimaginative as it is mean.

4/10

The film comes from an intolerably smug and cynical place - I am by no means a cheerleader for strong religious conviction and even less for evangelical Christianity, but the character Seidl and co-writer Veronika Franz have whipped up to anchor their ironic tale (though not as caustic in its ironies as Love) feels very much like an intensely, self-destructively religious woman as conceived by somebody who flat-out doesn't understand what faith consists of for the faithful. Anna Maria (Maria Hoffstätter) isn't a person, but a cartoon; and while Margarete Tiesel's Teresa in Love (Anna Maria's sister, a fact not even cryptically alluded to in Faith) is herself more of a conceptual construct than a recognisable human in some ways, the structure of that film's story and Tiesel's performance in it both help to make the film an exploration of her psychology in ways that feel at least plausible and grounded. Nothing of the sort for poor Anna Maria, whose obsession with sexual sinfulness results in scenes of her stripping naked and scourging herself, backing away from a far-too-convenient orgy in a park while fondling her rosary lustily, or rubbing her nether regions with a giant crucifix under the covers, in a scene that is meant to be a provocation, and comes off as a shrilly literal one that is far too silly and overwrought to offend or disturb anybody. It's paint-by-numbers "crazy sexually repressed religious hypocrite" writing that Hoffstätter is quite undone by; no actress could make a plausible character out of this being, and she ends up playing to the caricatured elements rather than modulating them with anything marginally human.

Insofar as Faith has a plot, it is this: some years ago, Anna Maria's husband, an Egyptian Muslim named Nabil (Nabil Saleh), disappeared. Now he has returned, a paraplegic - though it's left pointedly vague whether he was paraplegic before, and why he left, and whose decision that was. His return significantly upsets Anna Maria's plans for summer holiday, which include taking part in a prayer group enthusiastically planning to restore Catholicism to Austria, and marching door-to-door to do missioning work, aided by a foot-tall statue of the Virgin Mary that she positions in people's homes to make them worship with her. Having a man back in the house - a man who keeps bringing up sex, either in terms of desire or in terms of his inability to have it thanks to his condition - does absolutely no good to Anna Maria's successful attempts to eroticise Jesus, and the imbalance that Nabil's presence brings pretty quickly turns to violent lashing out on both sides, and unmistakably pan-denominational terrible behavior, and a vivid demonstration of just how truly good this hyper-devout woman actually is.

It is tediously programmatic, and it is horribly redundant; there aren't all that many points to be made and all of them are made in the first and last half-hours, which leads a huge chunk of movie devoted only to reiterating and repeating things we've already seen, and finding new ways to make Anna Maria's sexual repression creepier and more appalling. It is, altogether, the movie that Love kept threatening to be, and always managed to dodge away from: an unmitigated exercise in nastiness for the sake of nastiness, hysterical Austrian cinema of cruelty in which the main character is subjected to viciousness from herself and others that demonstrates to the audience nothing except our own capacity for watching self-flagellation before we grow bored of it. Whereas Love had some reasonably interesting things to say about social codes and self-definition (and also some very tired things to say about relations between Europe and Africa), Faith is delighted to traffic heavily in clichés both narrative and aesthetic, with its very samey feeling intensified rather than disguised by the savagery of what's being depicted onscreen.

There's one exception to all of this, and that's Anna Maria's missioning. Thrice in the movie, she ends up some poor victim's house to preach her deprivation-besotted version of Catholicism to them, and these shaggy scenes are by far the liveliest and most interesting scenes in the film, the only places where it feels like humans are involved and not blank spots on Seidl's Euroart Mad Libs. This despite feeling somewhat like improvisational acting exercises, where Hofstätter and the people she's acting against have each been given a single goal and told to spend five minutes chasing it without variation; but the way that these scenes spill out and go on past the point of reason (particularly the third, when Anna Maria struggles to give advice to a belligerent drunk) is, itself, fairly energetic and captivating, sort of like watching high-wire artists. There's always a sense that something will have to give, and it never does, and this ends up giving a much clearer insight into who Anna Maria is and why we might possibly want to study her more closely than all the self-abuse in the rest of the film could ever do.

Outside of those scenes, making up far too little of the overall running time, Faith is a whole lot of nothing: perfectly generic frames that stand still for very long in the fashion of glacial European art films, as a woman raves and raves and never gives us any insight into anything. If this is meant to give us some understanding about humanity, it fails on the level of lacking any humans; it its meant to shock us in our complacency, it fails on the level of being abysmally boring. This is the most rote, obnoxious kind of "fuck you, audience" filmmaking, as unimaginative as it is mean.

4/10