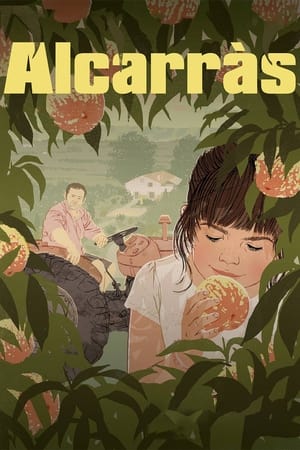

Carla Simón’s sophomore feature, Alcarràs, opens in a way that closely resembles her promising if somewhat amorphous debut, 2017’s Summer 1993. That film, as its title suggests, constituted a cine-memoir minutely recreating Simón’s childhood in northern Catalonia (an autonomous region of Spain), and she stuck firmly to a kid’s-eye view throughout. Alcarràs initially seems to be going the same route, as we first encounter Iris (Ainet Jounou), a little girl of perhaps six or seven, and her twin cousins Pau (Isaac Rovira) and Pere (Joel Rovira), playing an elaborate game of make-believe inside of a junked car that’s just sitting and slowly rusting in the middle of a field near a reservoir. Their antics are interrupted by the arrival of an enormous crane, which eventually removes their clubhouse and not-so-secret hideout. The best thing about this introductory salvo is that it’s not, in the moment, obviously symbolic. The worst thing about Alcarràs as a whole is Simón’s hell-bent insistence upon making that introductory salvo ponderously and retroactively symbolic, spinning her wheels until she can recreate it on a much larger scale.

But we’ll come back to that. As I implied above, Simón turns out to be doing something different here, though she’s still mining her own background for material. Alcarràs, a village in southwest Catalonia (but northeastern Spain), is where she grew up, and her family has a long history in peach farming, just like the fictional family of which Iris is the youngest member. Unlike Summer 1993, however, Alcarràs isn’t a period piece, and it doesn’t exclusively represent the dizzying experience of a small child. We spend time getting to know everyone, from elderly grandpa Rogelio (Josep Abad) to mom Dolors (Anna Otin) and dad Quimet (Jordi Pujol Dolcet) to teen son Roger (Albert Bosch) and pre-teen daughter Mariona (Xènia Roset). Plus Quimet’s brother Cisco (Carles Cabós) and his family (including Pau and Pere), and Quimet’s sister Glòria (Berta Pipó), who lives in Barcelona but frequently visits. It’s harvest time, so everyone—excepting the littlest kids, who, deprived of their beat-up car, run around getting in various people’s ways—is plenty busy picking ripened fruit from peach trees the family grows on land that, we soon discover, they do not own. What’s more, the land’s current owner, Pinyol (Jacob Diarte), has no interest in honoring the gentleman’s agreement that his ancestors made, which allowed the other family to farm their land in gratitude for having been saved by them back in the Spanish Civil War. Nobody had questioned this over many decades and multiple generations, but in the absence of an actual contract—and no such document exists—Pinyol intends to convert his land to a more profitable use.

That ostensibly dastardly plan is where Alcarràs takes what progressively comes to feel like a knee-jerk conservative direction. While Pinyol’s unmistakably meant to be the bad guy in this story, he doesn’t callously tell the other family to just take a hike. Instead, he offers Quimet a job at his new enterprise, insisting that it’ll be less backbreaking work for more money. Sounds too good to be true, and the cynical reader might assume that Pinyol’s planning to open a Wal-Mart or an Amazon fulfillment center on the property. (Nomadland certainly wouldn’t have hesitated to yank at our outrage ducts that way.) Ready for the reveal? Solar panels. Green energy. Cisco ultimately takes the offered position, to Quimet’s white-hot fury; peach farming is all Quimet has ever known, and he has zero interest, especially at his age (maybe mid-fifties), in learning a new trade. At no point does Simón portray this as a legitimate dilemma—we’re clearly expected to feel aggrieved on the family’s behalf, because they won’t be permitted to keep doing what they’ve always done. Perhaps to reinforce this simplistic tradition-good-modernity-bad dynamic, Simón has her onscreen family live and behave like time travelers from half a century ago. I noted earlier that Alcarràs isn’t a period piece, but anyone might mistakenly assume otherwise, as there’s nary a cellphone or computer in sight; when Mariona and her friends rehearse a dance routine outside, there’s no visible indication of where the music’s coming from.

I should belatedly note for the record that my relatively low opinion of this film is an outlier: Not only has Alcarràs received mostly stellar reviews, but it won the Golden Bear at last year’s Berlin Film Festival—the first Catalan-language film ever to do so. To a certain extent, I can understand why: Simón knows the region and its people intimately (all of the actors are local non-pros), and her affection and compassion permeate every frame. On top of which, we’re hard-wired to empathize with the underdog, so our own hearts naturally go out to a family that’s being forced to abandon its way of life. If dramatic complexity is your thing, on the other hand, you won’t find much of that in evidence here. The movie doesn’t have a plot to speak of, just a situation that remains stagnant throughout. We learn at the outset that the family’s going to be evicted (for lack of a better word), and then watch them fret about that for two hours, with only Cisco taking any active step to solve the problem. One potentially compelling result of this “betrayal” (as Quimet perceives it) is that the feuding parents employ their children as pawns, refusing out of sheer pique to let the cousins play together. As in Ira Sachs’ Little Men, though (which featured a very similar kids-in-the-crossfire scenario), that thorny element gets swamped by the larger, overly straightforward class conflict.

Part of what’s so frustrating is that Summer 1993 suggested a very different kind of filmmaker, and she’s still detectable here. Scenes observing the kids, whether at play or (in Roger and Mariona’s case) in adolescent turmoil, are uniformly terrific—there’s a wonderful, throwaway moment, toward the beginning, that has Dolors, who’s scrubbing Quimet’s back, ask Mariona to hand her some bath cream, which Mariona does…with her mouth, because she’s in the middle of painting her fingernails. (“You make things difficult, love,” Mom sighs as she tugs the tube from Mariona’s teeth.) Summer 1993 was almost 100% curated quotidian details of that sort, which was too much; Alcarràs gives us only enough to make its big ol’ thematic highlighter stand out even further. Those sensitive about onscreen violence toward animals, even when it’s not necessarily real (“Cap animal no ha estat maltractat o ferit durant el rodatge d'aquesta pel-lícula” reads a line in the end credits; it means what you’d assume), should know that more rabbits die for humanity’s sins here than in any movie since The Rules of the Game. The finale sees that monstrous crane from scene one return (it’s actually a different one, even bigger), this time to raze the family’s peach trees and to remind us of the little kids’ beloved old car: something that’s been deemed useless but still has immense value to those who love it. That’s not terrible symbolism per se, but getting from the foreshadow to the echo is a bit of a deterministic slog.

One of the first notable online film critics, having launched his site The Man Who Viewed Too Much in 1995, Mike D’Angelo has also written professionally for Entertainment Weekly, Time Out New York, The Village Voice, Esquire, Las Vegas Weekly, and The A.V. Club, among other publications. He’s been a member of the New York Film Critics Circle and currently blathers opinions almost daily on Patreon.