What child is this

A review requested by Nathan, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

Tokyo Godfathers, from 2003, is the weirdest of the five major projects completed by the great Japanese animation director Kon Satoshi entirely by virtue of being not very weird at all. His first two films - 1997's Perfect Blue and 2001's Millennium Actress - are both complicated stories about unstable identities getting tangled up with possibly corrupted memories (and the second of them is a real structural mindfuck, too). His two subsequent projects - the 2004 television series Paranoia Agent and the 2006 feature Paprika are both (get this) complicated stories about unstable identities getting tangled up with possibly corrupted memories (and the second of them is a real structural mindfuck, too).

Tokyo Godfathers, in contrast - extreme contrast - is a very nice social realist Christmas story that's a remake of an unusually sentimental John Ford Western, the 1948 film 3 Godfathers (which was no less than the fifth feature adaptation of Peter B. Kyne's 1913 novel The Three Godfathers, though I think nobody would disagree if I said it has been regarded as the definitive one). I cannot think of any possible reckoning of Kon's filmography that wouldn't consider it the wild outlier, and for a lot of people, that also means it's the weakest. If I am being entirely honest "a lot of people" here includes me, but not because I have any particular axe to grind against Tokyo Godfathers, which I think is a very lovely and remarkable work. It's more that something needs to be Kon's "worst" movie, basically by definition, and this is the only one of his five remarkable achievements - cumulatively, the most impressive body of work produced by any Japanese director working in animation* - that's merely great, rather than something that redefines the possibilities of the medium, both in the stories that can be told and the artwork that can be used to tell them (though it was, for what it's worth, Kon's first film made with a digital workflow; there are a few backgrounds and snow effects that take advantage of that, but mostly I don't think you can tell)

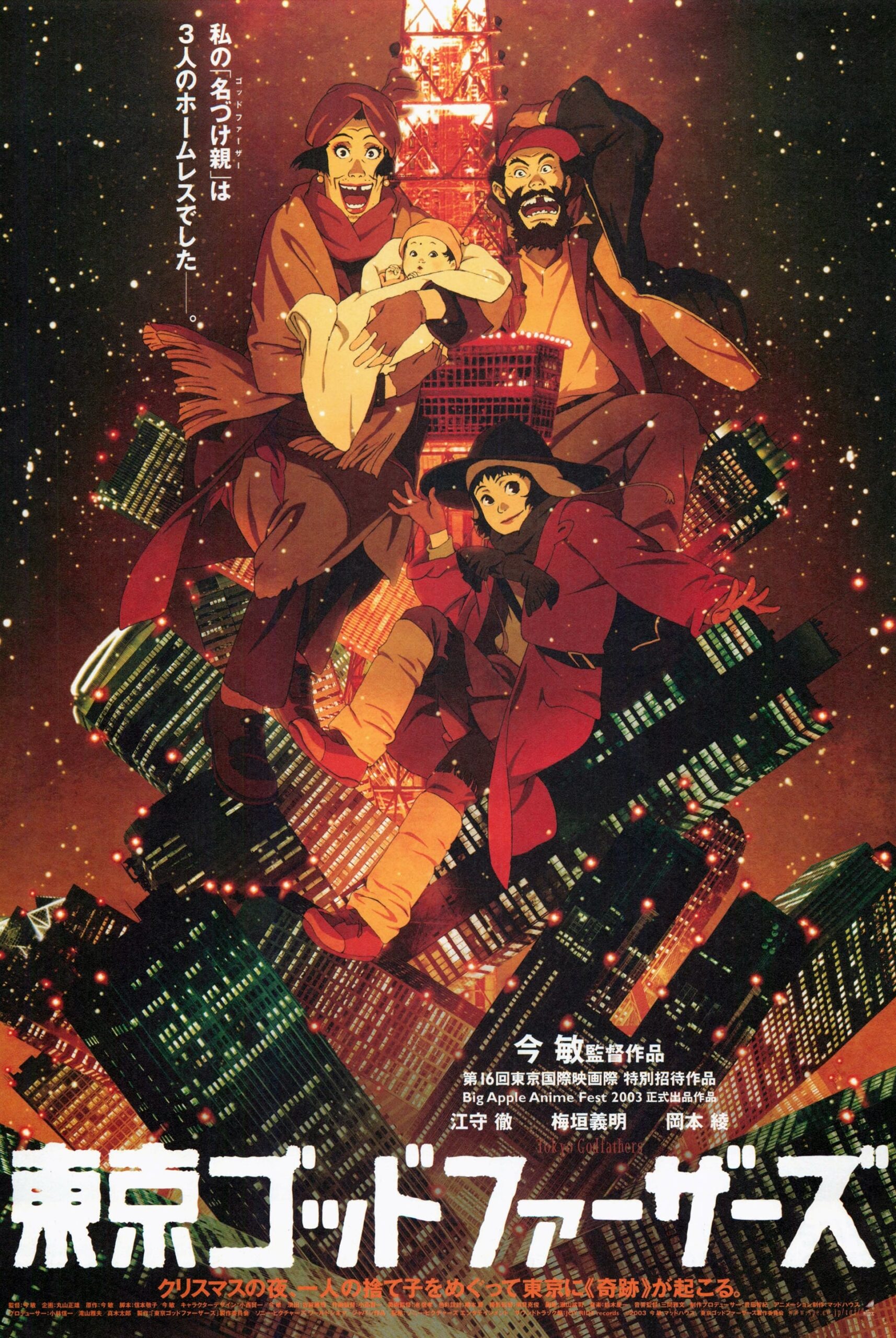

Still and all, this is unmistakably a Kon film; you need only glance at the character designs to see that. Indeed, from a design standpoint, characters and backgrounds alike, Tokyo Godfathers feels almost exactly like Paranoia Agent, which operates at a similar level of grotesque realism. Only here that's funneled into a sweet-natured character drama about people who need people, which makes the grotesque qualities feel more about celebrating human eccentricities with love, less like creating a nightmare of distorted human shortcomings. But the general feeling, that Kon and animation director Konishi Kenichi's character designs are providing a funhouse mirror of our own world and especially the unpolished and grotty parts of it, is uncannily similar between the two.

The grotty, unpolished, but lovable humanity at the center of Tokyo Godfathers largely consists of three homeless people whom we first meet when they're attending a free sermon and Christmas pageant on 24 December, presumably for the primary reason of the free dinner to follow those two other things. Each of the protagonists has arrived at their dissolute state for a different reason, which among other things allows Kon and co-writer Nobumoto Keiko to create a kind of broad consideration of homelessness in several different forms, though it's a credit to the subtlety of their character work that at no point does Tokyo Godfathers ever feel even slightly schematic. Gin (Emori Tōru) is an alcoholic man whose substance abuse problems, along with other ill-advised decisions, left him an outcast from his family, and society at large. Hana (Umegaki Yoshiaki) is a transwoman who ran out of support networks to keep her safe from the judgmental bullies of a hostile society. And Miyuki (Okamoto Aya) is a pretty standard-issue teenage runaway. They're acquaintances more than anything else when we first see them, but the events of the film end up throwing them into one of those "found families" who show up in movies like this. And those events are largely predicated upon discovering, in a pile of trash, a newborn baby who has been abandoned with a vague note asking the finders to take good care of her. Hana, who immediately latches onto the child as an outlet for her own frustrated maternal instincts, suggests naming the girl "Kiyoko", derived from the translated lyrics of "Silent Night" that had just been performed during that free pageant. Thus begins a story that takes place over a few days between Christmas and New Year's Day, as the three outcasts try to find a safe place for Kiyoko to know the love and protection that she won't get if they just deposit her with cops. And would you suppose that it also involves the three leads simultaneously finding love and protection from each other, giving them room to finally move beyond the hurts, self-inflicted or otherwise, that have brought them to this low place? It is a Christmas movie, after all.

And, I'm happy to say, a pretty damn good one. Kon is no sentimentalist, and while the story of Tokyo Godfathers lands in some unabashedly sentimental-looking places, it takes an offbeat, even slightly morbid path to get there. The film is a strange kind of tragicomedy, in which the saddest parts are just the ones where the characters are sitting around doing not much (a lot of this is centered around Hana, who by virtue of being the only one of the three protagonists who ever displays an optimistic, happy attitude, is the only one who can have that optimism disappear in a cloud of depressed rage at the cold, loveless world she's been navigating her whole life); the comic parts are frequently where things ought to be more tense or sober or bleak. There's a random background gag that consists solely of a passerby getting walloped by car; near the end of the film, there's a thrilling chase-oriented setpiece attempting to prevent a woman from committing suicide that is turned into a jaunty, goofy romp, largely through the application of the music by Suzuki Keiichi, of the art-rock group Moonriders. Music is, in fact, one of the most distinctive elements of Tokyo Godfathers; it provides the deadpan weirdness that the script isn't touching, providing odd jazz-like riffs on Christmassy motifs, and generally suggesting that happy moments are terrifying and sad moments are silly. It's pretty great, and certainly unexpected.

All of which is to say: the film's path to a conventional Christmas finale, in which the very city itself seems to be smiling with yuletide joy (Kon made extensive use of background paintings that subtly anthropomorphise buildings; also, the film ends with the city skyline literally dancing to a peppy, techno-ish recording of Beethoven's "Ode to Joy"), goes through some dark and ugly and violent places. Tokyo Godfathers isn't "about" homelessness, in the sense of being a message movie (indeed, by more or less directly stating that Gin got here because he made bad choices and he needs to make up for those choices, it is perhaps an anti-message movie, at least in that way), but it is about being someone who doesn't have someplace to go, because the world is a dirty and cruel place that sometimes just shuts you out. It's presenting a vision of Tokyo as a rough place full of dark corners and garbage, pointedly avoiding strong, festive colors in favor of a palette that is addicted to rusty browns. This is occasionally diluted by moments where striking, at times ethereal lighting effects are pulled in to make something beautiful and maybe a little sacred out of the grunginess of the setting. And that, of course,is where it is a Christmas movie at heart, one that believes in the possibility that everything can be redeemed, no matter how bad it has gone.

I think it would be possible to nitpick bits and pieces of it - Gin gets a more clearly defined character arc than Hana, and Miyuki barely gets one at all; it shifts into a car-chase climax that I don't think plays very well, and feels like it comes from some weird assumption of what animation is "meant" to do that hardly applies to the Japanese context, or Kon's career - but I think it would also be fairly mean-spirited to nitpick it. This is a lovely film, generous towards it characters even as it allows them to act and look flawed and even gross. That's a tough balance to strike, and Tokyo Godfathers wagers pretty much the entirety of its 92-minute running time on being able to always make it work. That it does so for essentially every one of those minutes is its own form of Christmas miracle. This is easily Kon's least-flashy, least-radical film, but it's also the work of a tremendously gifted storyteller, one who had to this point demonstrated that he could do incredible work sketching out broken personalities, but had never been so humane in letting those personalities reassemble themselves. It's an extremely big-hearted movie, all the more since it never acts like having a big heart is easy.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

*You could probably cherry-pick a top five from Yuasa Masaaki, Miyazaki Hayao, or Isao Takahata that would at least give Kon's five titles a run for their money, but that would be cheating. And even so, I'd still probably stick with Kon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

Tokyo Godfathers, from 2003, is the weirdest of the five major projects completed by the great Japanese animation director Kon Satoshi entirely by virtue of being not very weird at all. His first two films - 1997's Perfect Blue and 2001's Millennium Actress - are both complicated stories about unstable identities getting tangled up with possibly corrupted memories (and the second of them is a real structural mindfuck, too). His two subsequent projects - the 2004 television series Paranoia Agent and the 2006 feature Paprika are both (get this) complicated stories about unstable identities getting tangled up with possibly corrupted memories (and the second of them is a real structural mindfuck, too).

Tokyo Godfathers, in contrast - extreme contrast - is a very nice social realist Christmas story that's a remake of an unusually sentimental John Ford Western, the 1948 film 3 Godfathers (which was no less than the fifth feature adaptation of Peter B. Kyne's 1913 novel The Three Godfathers, though I think nobody would disagree if I said it has been regarded as the definitive one). I cannot think of any possible reckoning of Kon's filmography that wouldn't consider it the wild outlier, and for a lot of people, that also means it's the weakest. If I am being entirely honest "a lot of people" here includes me, but not because I have any particular axe to grind against Tokyo Godfathers, which I think is a very lovely and remarkable work. It's more that something needs to be Kon's "worst" movie, basically by definition, and this is the only one of his five remarkable achievements - cumulatively, the most impressive body of work produced by any Japanese director working in animation* - that's merely great, rather than something that redefines the possibilities of the medium, both in the stories that can be told and the artwork that can be used to tell them (though it was, for what it's worth, Kon's first film made with a digital workflow; there are a few backgrounds and snow effects that take advantage of that, but mostly I don't think you can tell)

Still and all, this is unmistakably a Kon film; you need only glance at the character designs to see that. Indeed, from a design standpoint, characters and backgrounds alike, Tokyo Godfathers feels almost exactly like Paranoia Agent, which operates at a similar level of grotesque realism. Only here that's funneled into a sweet-natured character drama about people who need people, which makes the grotesque qualities feel more about celebrating human eccentricities with love, less like creating a nightmare of distorted human shortcomings. But the general feeling, that Kon and animation director Konishi Kenichi's character designs are providing a funhouse mirror of our own world and especially the unpolished and grotty parts of it, is uncannily similar between the two.

The grotty, unpolished, but lovable humanity at the center of Tokyo Godfathers largely consists of three homeless people whom we first meet when they're attending a free sermon and Christmas pageant on 24 December, presumably for the primary reason of the free dinner to follow those two other things. Each of the protagonists has arrived at their dissolute state for a different reason, which among other things allows Kon and co-writer Nobumoto Keiko to create a kind of broad consideration of homelessness in several different forms, though it's a credit to the subtlety of their character work that at no point does Tokyo Godfathers ever feel even slightly schematic. Gin (Emori Tōru) is an alcoholic man whose substance abuse problems, along with other ill-advised decisions, left him an outcast from his family, and society at large. Hana (Umegaki Yoshiaki) is a transwoman who ran out of support networks to keep her safe from the judgmental bullies of a hostile society. And Miyuki (Okamoto Aya) is a pretty standard-issue teenage runaway. They're acquaintances more than anything else when we first see them, but the events of the film end up throwing them into one of those "found families" who show up in movies like this. And those events are largely predicated upon discovering, in a pile of trash, a newborn baby who has been abandoned with a vague note asking the finders to take good care of her. Hana, who immediately latches onto the child as an outlet for her own frustrated maternal instincts, suggests naming the girl "Kiyoko", derived from the translated lyrics of "Silent Night" that had just been performed during that free pageant. Thus begins a story that takes place over a few days between Christmas and New Year's Day, as the three outcasts try to find a safe place for Kiyoko to know the love and protection that she won't get if they just deposit her with cops. And would you suppose that it also involves the three leads simultaneously finding love and protection from each other, giving them room to finally move beyond the hurts, self-inflicted or otherwise, that have brought them to this low place? It is a Christmas movie, after all.

And, I'm happy to say, a pretty damn good one. Kon is no sentimentalist, and while the story of Tokyo Godfathers lands in some unabashedly sentimental-looking places, it takes an offbeat, even slightly morbid path to get there. The film is a strange kind of tragicomedy, in which the saddest parts are just the ones where the characters are sitting around doing not much (a lot of this is centered around Hana, who by virtue of being the only one of the three protagonists who ever displays an optimistic, happy attitude, is the only one who can have that optimism disappear in a cloud of depressed rage at the cold, loveless world she's been navigating her whole life); the comic parts are frequently where things ought to be more tense or sober or bleak. There's a random background gag that consists solely of a passerby getting walloped by car; near the end of the film, there's a thrilling chase-oriented setpiece attempting to prevent a woman from committing suicide that is turned into a jaunty, goofy romp, largely through the application of the music by Suzuki Keiichi, of the art-rock group Moonriders. Music is, in fact, one of the most distinctive elements of Tokyo Godfathers; it provides the deadpan weirdness that the script isn't touching, providing odd jazz-like riffs on Christmassy motifs, and generally suggesting that happy moments are terrifying and sad moments are silly. It's pretty great, and certainly unexpected.

All of which is to say: the film's path to a conventional Christmas finale, in which the very city itself seems to be smiling with yuletide joy (Kon made extensive use of background paintings that subtly anthropomorphise buildings; also, the film ends with the city skyline literally dancing to a peppy, techno-ish recording of Beethoven's "Ode to Joy"), goes through some dark and ugly and violent places. Tokyo Godfathers isn't "about" homelessness, in the sense of being a message movie (indeed, by more or less directly stating that Gin got here because he made bad choices and he needs to make up for those choices, it is perhaps an anti-message movie, at least in that way), but it is about being someone who doesn't have someplace to go, because the world is a dirty and cruel place that sometimes just shuts you out. It's presenting a vision of Tokyo as a rough place full of dark corners and garbage, pointedly avoiding strong, festive colors in favor of a palette that is addicted to rusty browns. This is occasionally diluted by moments where striking, at times ethereal lighting effects are pulled in to make something beautiful and maybe a little sacred out of the grunginess of the setting. And that, of course,is where it is a Christmas movie at heart, one that believes in the possibility that everything can be redeemed, no matter how bad it has gone.

I think it would be possible to nitpick bits and pieces of it - Gin gets a more clearly defined character arc than Hana, and Miyuki barely gets one at all; it shifts into a car-chase climax that I don't think plays very well, and feels like it comes from some weird assumption of what animation is "meant" to do that hardly applies to the Japanese context, or Kon's career - but I think it would also be fairly mean-spirited to nitpick it. This is a lovely film, generous towards it characters even as it allows them to act and look flawed and even gross. That's a tough balance to strike, and Tokyo Godfathers wagers pretty much the entirety of its 92-minute running time on being able to always make it work. That it does so for essentially every one of those minutes is its own form of Christmas miracle. This is easily Kon's least-flashy, least-radical film, but it's also the work of a tremendously gifted storyteller, one who had to this point demonstrated that he could do incredible work sketching out broken personalities, but had never been so humane in letting those personalities reassemble themselves. It's an extremely big-hearted movie, all the more since it never acts like having a big heart is easy.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

*You could probably cherry-pick a top five from Yuasa Masaaki, Miyazaki Hayao, or Isao Takahata that would at least give Kon's five titles a run for their money, but that would be cheating. And even so, I'd still probably stick with Kon.