He's making me feel like I've never been born

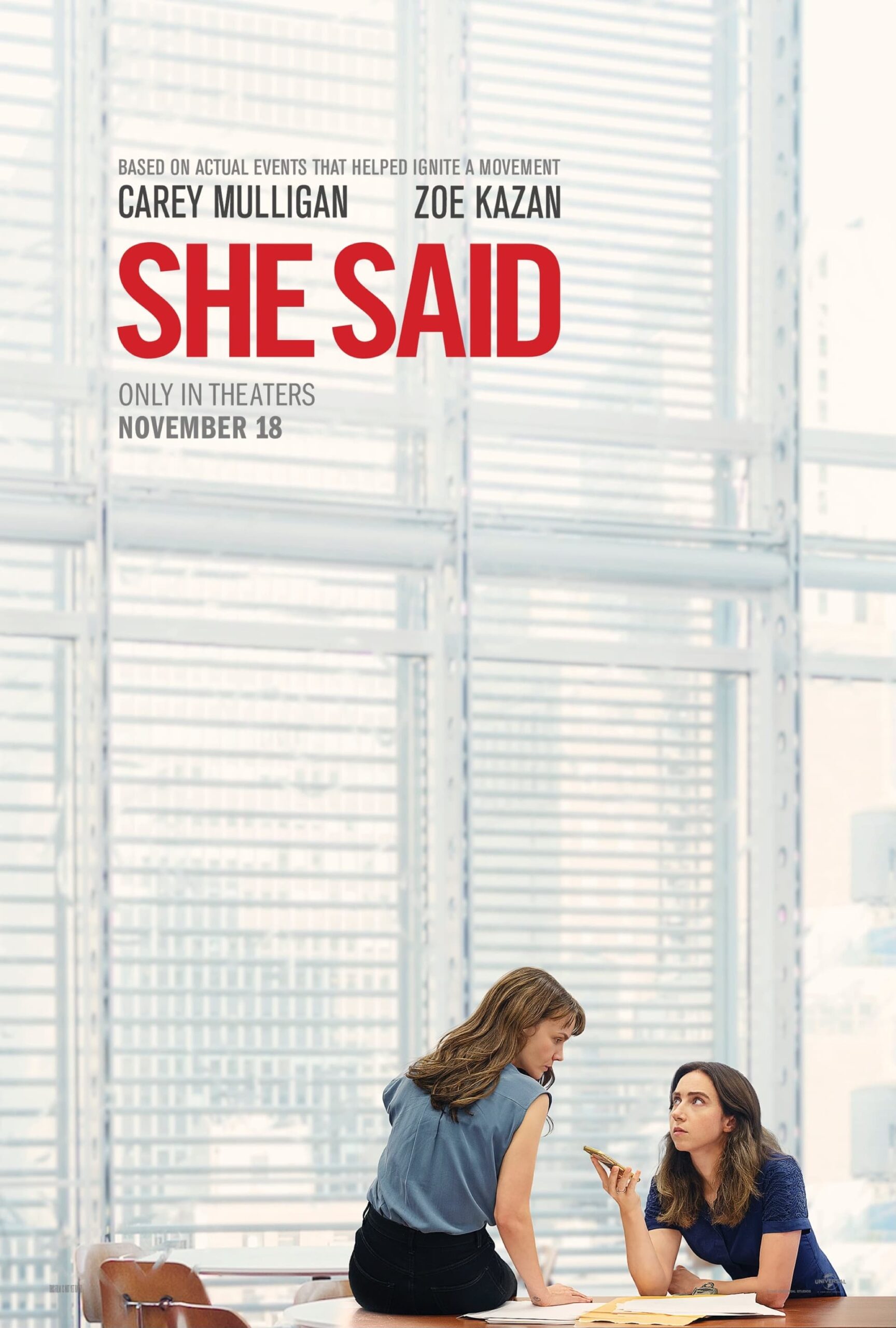

In all my movie-going years, I have only very rarely encountered a film whose entire conceit screamed "come here and eat this huge plate of raw lima beans, because this is extremely serious and important" the way that She Said does. It's a ripped-from-the-headlines story with the uncommon twist that we can point directly to the single headline from which it was ripped: "Harvey Weinstein Paid Off Sexual Harassment Accusers for Decades", published in The New York Times on 5 October 2017. She Said is the story of how NYT reporters Jodi Kantor (Zoe Kazan) and Megan Twohey (Carey Mulligan) investigated and wrote that story, and the film culminates with their article going live before the world. It is, as such, a story that wants to carry all the weight of the subsequent #MeToo movement and the destruction of Weinstein's career on its shoulders. Feels like pretty dubiously self-important and self-congratulatory stuff, even without making note of the ludicrous hypocrisy involved in a major studio like Universal making a big Oscar-hopeful prestige movie about the hunt to bring Weinstein to justice, when his crimes were a barely-hidden open secret in the industry for some two decades and nobody in the industry, including some of the very people involved in this film's production, ever gave a shit until it became politically awkward not to.

Anyway, I walked into the film expecting the absolute worse, and to my enormous surprise, She Said is fine, with some individual elements that are legitimately great. Replace Zoe Kazan with literally any other actress now working in the anglosphere, and the whole thing would instantly rise up to "pretty damn good", the way that removing a lead weight from a toy boat will cause it to suddenly bob up in the water and make a series of merry ripples. The absolute peak that She Said was ever going to be capable of hitting, quality was, was "almost but not quite as good as Spotlight", and I genuinely do think its best moments walk right up that line.

Regrettable, it's got plenty of bad moments to go along with those best moments, and the bad moments are significantly frontloaded. The film's structure... doesn't exist. But if it did, I'd have started that sentence as, The film's structure begins with a couple of flashbacks, one to an event that seems totally dissociated from the rest of the story, and eventually sort of hooks back into it, but not so robustly, or to such a "aha! I get it now!" payoff that it seems worth all of the muddiness. The other one also remains mostly dissociated from the rest of the story, though it at least kind of explains why the film's version of Megan Twohey is so enraged at the world as the story begins (short version: she discovered, firsthand, that The New York Times didn't have the ability to prevent Donald Trump from winning the 2016 U.S. presidential election). Still, it feels like the film is just kind of hopscotching around through fragments of history, and nothing counteracts that feeling for a very long time. Insofar as this endless stream of detached, module-like scenes falls into "acts", the entire "first act" is nothing but little snippets in the lives of Kantor and Twohey, both professional and personal. These snippets all last for what feels like a half of a minute, and steadfastly refuse to build up any momentum as they go; if I were going to come up with the most charitable possible explanation for what the hell is going on that I could come up with, it would be to suppose that these little eyeblinks of narrative are meant to represent the reporters' sense of aimlessness in a world that seems capricious and wrong and meanspirited, but that's stretching till I dislocate something. Eventually, Kantor starts nosing around in what seems to be a promising story about some payoffs that Weinstein's people made to various women who have signed nondisclosure arguments, and the script's profound shapelessness can be forced into a different metaphor, for the frustrating lack of momentum the leads face in finding a whole bunch of dead ends and women who get terribly panicked and horror-stricken just from hearing that The New York Times is interested in what happened to them, and this at least isn't a self-evidently fake justification. But it's still pretty damn annoying to watch She Said as it just keeps racking up little tiny scenelets in which effectively nothing happens.

This all raises the question of what on Earth the point of this movie could possibly be: it' pretty much impossible to imagine the viewer who didn't already know exactly what Kantor and Twohey ended up finding out, and what the fallout from their article would prove to be, even slightly being able to make sense of this anti-plot; it relies on its audience having all of the necessary knowledge to fill in a whole lot of background. Particularly during this incredibly aimless opening, where it's not even slightly clear what the reporters are actually looking into, or why they thought it might be worth looking into it.

It's a pretty dire opening, not just clumsily expressed in Rebecca Lenkiewicz's script, but chopped together by Hansjörg Weißbrich without rhythm or a clear sense of space, and the only anchor for most of it is Kazan's helpless performance, consisting of virtually nothing other than great big wide-eyed expressions of vague despair that make her look like a cross kitten. Everything changes the moment that Twohey comes on to help with the investigation, called upon because of her expertise in getting victims of sexual harassment to share their uncomfortable stories while feeling safe and cared for, at which point three things happen. First, Twohey actually starts to impact the plot, rather than the film just cutting to her as she looks around with a melancholic air of post-partum depression, and this helps enormously with the sense of pacing and structure. Second, Mulligan starts to get actual stuff to do, and you can almost feel the film sigh with relief that it has a capital-P Performance made up of capital-A Acting to showcase, rather than Kazan continuing to knit her brow sternly in an attempt to play a grown-up. Indeed, Mulligan's performance proves to be not just a highlight of She Said, but of the whole 2022 movie year. She's going extremely small while still evoking huge, furious emotions; as she confronts one fragment of evidence after another demonstrating the savagery of the sexist system protecting Weinstein, you can almost watch her crunching her teeth into powder, while leaving her eyes relaxed and unfocused, as though she can't actually think too hard about what she's encountering without exploding. Everything she does is a tiny, tossed-off gesture, as simple as how she slightly winces at hearing this or that venal male asshole, or the pauses she takes to breathe before speaking.

The third thing that happens is that we get the testimony of what happened to these women, and director Maria Schrader begins to trot out the rather impressive tricks she'll be using to dramatise these events without actually dramatising them; the heart of She Said's project is to never show anything prurient or exploitative, to honor the great emotional toll of the testimony of what, as it were she said, without transforming it into Movie Stuff. And the most potent and powerful of these sequences is the first, with staticky archival audio ofone of these horrific encounters with Weinstein playing over the most banal zoom shots of empty hotel hallways. It's shocking and gut-wrenching precisely because it offers not the slightest hint of aesthetic release; we're just stuck with the audio and our own imaginations.

As it so happens, once the film gets going, Schrader's directing really starts to sharpen up and create some brilliant moments: if not the bleakness of hearing these stories, then the crisp professionalism of watching NYT reporters clip away at their work - in the actual NYT offices, no less, playing themselves in a narrative feature for the first time ever. There's a cool, unsentimental look at the work of journalism that pushes hard against the film's message movie impulses, and puts this at least in the lineage of the great newspaper movies, if only on a scene-by-scene basis. The film favors static group shots, emphasising the collaborative nature of this story, and making room for many wonderful supporting performances, from the grounded calm of Patricia Clarkson as editor Rebecca Corbett to the tightly-wound fury of Samantha Morton as a frustrated witness to Jennifer Ehle's incredibly potent performance as one of Weinstein's victims, now middle-aged and facing her mortality, and serving as the necessary human counterweight to the procedural elements.

It never completely solves its problems: the editing, in particular, never quite rights itself, and there are some pretty shabby attempts to move us around rooms or other spaces throughout. And it also never comes close to solving that central problem with the writing, where the characters always talk as if they know that they're in a prestige movie angling for awards about recent historical events, and are more concerned with sound portentous than actually telling a legible story that could explain any of this if you didn't already know what was going on. She Said is a pretty rough message movie, even at its best. But that was always going to be the worst part about it, and given how well it works as a journalism procedural, I'm hardly going to weep any tears that it's not better at being a moralistic harangue.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

Anyway, I walked into the film expecting the absolute worse, and to my enormous surprise, She Said is fine, with some individual elements that are legitimately great. Replace Zoe Kazan with literally any other actress now working in the anglosphere, and the whole thing would instantly rise up to "pretty damn good", the way that removing a lead weight from a toy boat will cause it to suddenly bob up in the water and make a series of merry ripples. The absolute peak that She Said was ever going to be capable of hitting, quality was, was "almost but not quite as good as Spotlight", and I genuinely do think its best moments walk right up that line.

Regrettable, it's got plenty of bad moments to go along with those best moments, and the bad moments are significantly frontloaded. The film's structure... doesn't exist. But if it did, I'd have started that sentence as, The film's structure begins with a couple of flashbacks, one to an event that seems totally dissociated from the rest of the story, and eventually sort of hooks back into it, but not so robustly, or to such a "aha! I get it now!" payoff that it seems worth all of the muddiness. The other one also remains mostly dissociated from the rest of the story, though it at least kind of explains why the film's version of Megan Twohey is so enraged at the world as the story begins (short version: she discovered, firsthand, that The New York Times didn't have the ability to prevent Donald Trump from winning the 2016 U.S. presidential election). Still, it feels like the film is just kind of hopscotching around through fragments of history, and nothing counteracts that feeling for a very long time. Insofar as this endless stream of detached, module-like scenes falls into "acts", the entire "first act" is nothing but little snippets in the lives of Kantor and Twohey, both professional and personal. These snippets all last for what feels like a half of a minute, and steadfastly refuse to build up any momentum as they go; if I were going to come up with the most charitable possible explanation for what the hell is going on that I could come up with, it would be to suppose that these little eyeblinks of narrative are meant to represent the reporters' sense of aimlessness in a world that seems capricious and wrong and meanspirited, but that's stretching till I dislocate something. Eventually, Kantor starts nosing around in what seems to be a promising story about some payoffs that Weinstein's people made to various women who have signed nondisclosure arguments, and the script's profound shapelessness can be forced into a different metaphor, for the frustrating lack of momentum the leads face in finding a whole bunch of dead ends and women who get terribly panicked and horror-stricken just from hearing that The New York Times is interested in what happened to them, and this at least isn't a self-evidently fake justification. But it's still pretty damn annoying to watch She Said as it just keeps racking up little tiny scenelets in which effectively nothing happens.

This all raises the question of what on Earth the point of this movie could possibly be: it' pretty much impossible to imagine the viewer who didn't already know exactly what Kantor and Twohey ended up finding out, and what the fallout from their article would prove to be, even slightly being able to make sense of this anti-plot; it relies on its audience having all of the necessary knowledge to fill in a whole lot of background. Particularly during this incredibly aimless opening, where it's not even slightly clear what the reporters are actually looking into, or why they thought it might be worth looking into it.

It's a pretty dire opening, not just clumsily expressed in Rebecca Lenkiewicz's script, but chopped together by Hansjörg Weißbrich without rhythm or a clear sense of space, and the only anchor for most of it is Kazan's helpless performance, consisting of virtually nothing other than great big wide-eyed expressions of vague despair that make her look like a cross kitten. Everything changes the moment that Twohey comes on to help with the investigation, called upon because of her expertise in getting victims of sexual harassment to share their uncomfortable stories while feeling safe and cared for, at which point three things happen. First, Twohey actually starts to impact the plot, rather than the film just cutting to her as she looks around with a melancholic air of post-partum depression, and this helps enormously with the sense of pacing and structure. Second, Mulligan starts to get actual stuff to do, and you can almost feel the film sigh with relief that it has a capital-P Performance made up of capital-A Acting to showcase, rather than Kazan continuing to knit her brow sternly in an attempt to play a grown-up. Indeed, Mulligan's performance proves to be not just a highlight of She Said, but of the whole 2022 movie year. She's going extremely small while still evoking huge, furious emotions; as she confronts one fragment of evidence after another demonstrating the savagery of the sexist system protecting Weinstein, you can almost watch her crunching her teeth into powder, while leaving her eyes relaxed and unfocused, as though she can't actually think too hard about what she's encountering without exploding. Everything she does is a tiny, tossed-off gesture, as simple as how she slightly winces at hearing this or that venal male asshole, or the pauses she takes to breathe before speaking.

The third thing that happens is that we get the testimony of what happened to these women, and director Maria Schrader begins to trot out the rather impressive tricks she'll be using to dramatise these events without actually dramatising them; the heart of She Said's project is to never show anything prurient or exploitative, to honor the great emotional toll of the testimony of what, as it were she said, without transforming it into Movie Stuff. And the most potent and powerful of these sequences is the first, with staticky archival audio ofone of these horrific encounters with Weinstein playing over the most banal zoom shots of empty hotel hallways. It's shocking and gut-wrenching precisely because it offers not the slightest hint of aesthetic release; we're just stuck with the audio and our own imaginations.

As it so happens, once the film gets going, Schrader's directing really starts to sharpen up and create some brilliant moments: if not the bleakness of hearing these stories, then the crisp professionalism of watching NYT reporters clip away at their work - in the actual NYT offices, no less, playing themselves in a narrative feature for the first time ever. There's a cool, unsentimental look at the work of journalism that pushes hard against the film's message movie impulses, and puts this at least in the lineage of the great newspaper movies, if only on a scene-by-scene basis. The film favors static group shots, emphasising the collaborative nature of this story, and making room for many wonderful supporting performances, from the grounded calm of Patricia Clarkson as editor Rebecca Corbett to the tightly-wound fury of Samantha Morton as a frustrated witness to Jennifer Ehle's incredibly potent performance as one of Weinstein's victims, now middle-aged and facing her mortality, and serving as the necessary human counterweight to the procedural elements.

It never completely solves its problems: the editing, in particular, never quite rights itself, and there are some pretty shabby attempts to move us around rooms or other spaces throughout. And it also never comes close to solving that central problem with the writing, where the characters always talk as if they know that they're in a prestige movie angling for awards about recent historical events, and are more concerned with sound portentous than actually telling a legible story that could explain any of this if you didn't already know what was going on. She Said is a pretty rough message movie, even at its best. But that was always going to be the worst part about it, and given how well it works as a journalism procedural, I'm hardly going to weep any tears that it's not better at being a moralistic harangue.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

Categories: message pictures, oscarbait, very serious movies