Fine young cannibals

Bones and All, the seventh feature film directed by Luca Guadagnino, is kind of about cannibalism, and this is where it gets itself into trouble. No film should be "kind of" about cannibalism. Some subjects just don't allow for half measures. You should never walk out of a film whose protagonists are cannibals - bisexual cannibals, even! - and say, "well, I liked that, but I'm not entirely sure that the cannibalism scenes worked." It should, must either be the thing that is most dominant and exciting and challenging part of the movie, or it should leave you furious and disgusted and enraged and in a simply dreadful mood altogether. If you're giving a noncommittal shrug to the cannibalism bits, something has gone awry.

Possibly, this is a me problem. At any rate, I found myself wishing, multiple times in Bones and All, that it would either be more of a cannibal movie or not at all a cannibal movie, but that it at any rate was the wrong amount of cannibal movie. Cannibalism here is largely used as a metaphor, about being the kind of person who doesn't fit in properly to society and gravitates towards the small handful of people you meet in the rural, conservative-ish parts of the United States who have your same kind of not-fitting-in qualities - it's walking right up to knocking on the door of queer allegory while not quite limiting itself to that reading. And that's a tough metaphor to make work, since cannibalism is also used here as the disgusting violent crime that results in the hideous, blood-soaked deaths of innocents.

Since I'm not going to get very far dwelling on any of that, let us for now set aside the cannibalism - and again, "let us set aside the cannibalism" is just not a phrase one likes to trot out in a postive review - and attend to the things that work very well. For, whatever else we might say about it, Bones and All is still a Luca Guadagnino film, and even as he's making what I think is pretty clearly his most unsuccessful feature film since his big international breakthrough with 2009's I Am Love, he's still one of our foremost sensualists. And such a worthy subject he's turning his sensualism towards this time: with Bones and All, Guadagnino joins the grand tradition of European art film directors turning their visual sensibilities towards the remarkable, grand, tacky, vibrant, flat, and above all else really fucking big North American continent. In other words, this is his "European master makes a travelogue about the U.S." movie, a genre I am always captivated by even when the results seem at least a bit unsteady on their feet.

And as far as being a travelogue, at least, I don't think Bones and All is the least bit unsteady. It's a story of a great sweeping journey from Virginia up into Indiana, back down through Kentucky and then across Missouri and Iowa to get to Minnesota, and then back a little bit, and while it's not covering nearly as much ground as it claims to - the bulk of the shooting took place in Ohio - it still captures a lot of the particular qualities of the central part of the U.S., both the warm beauty of golden hour light on wheat fields and failing small towns, and the tiresome, lonely isolation and dustiness that blankets most of the Midwest. It's a downright Days of Heaven-esque quantity of prairie sunsets that Guadagnino and cinematographer Arseni Khachaturan (who seems to have come from basically nowhere at all to suddenly collaborate with a big-name art director on his first major release) have gifted us with. And I don't even think it's just beauty for the sake of beauty, either; this film is all about the overwhelming emo Romanticism of teen outcasts in love, with each other and with life and with freedom and with The Open Road, and all that. It's damn near schmaltzy in its celebration of youthful romance, particularly in its song choices, and only the aura of horror and disgust that never quite dissipates keeps it from hitting that point.

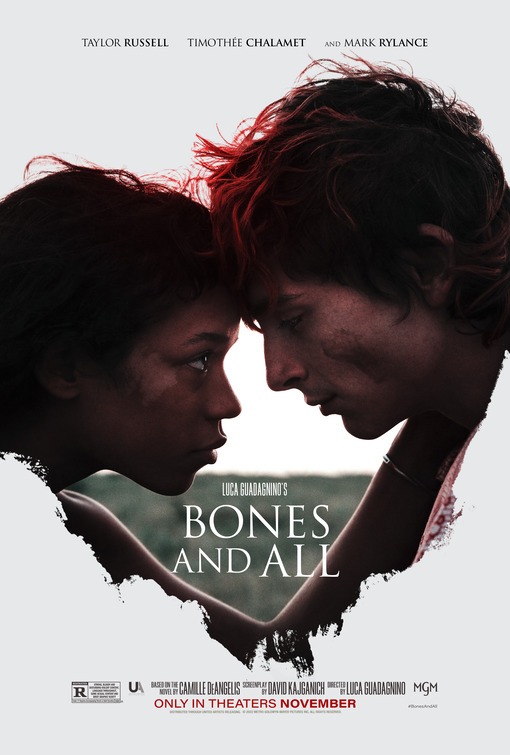

The romantic teenage cannibal lovers in question, for the record, are Maren (Taylor Russell), around 17, and Lee (Timothée Chalamet), at least a few years older, and they're both what is named by at least one person as "eaters" - humans who have, for reasons unknown and totally unexplored, been born with a genetic abnormality that makes them need to ingest the flesh of other humans, assuming they still count as the same species. If they don't, they go a bit deranged. All of this is explained, in a halting, disordered fashion by a much older "eater", Sully, played by Mark Rylance in a portrait of warped obsession that is, at the very least, committed as hell, even if not one other thing about Bones and All is in the same register of nightmare camp as Rylance's performance. He's the first of their kind encountered by Maren after she's abandoned suddenly by her father (André Holland), who hits the inevitable point where he fears his daughter more than he loves her one morning near the start of the film. The rest of the film is very loosely structured around Maren and Lee, traveling together first out of convenience, then out of mutual attraction, then out of desperate need, encountering various cameos that generally do the most to push this back torward horror: Rylance comes back a couple more times, to increasingly diminished returns (the third and final appearance, in particular, is lousy with "look, we had to move the plot forward somehow" vibes), and we also get to spend time with Michael Stuhlbarg, fellow "sunkissed American" director David Gordon Green, Jake Horowitz, Chloë Sevigny (whose fearlessly weird performance is the closest anybody comes to matching Rylance), and best of all, Jessica Harper, continuing her lifelong record of being among the most strikingly off-kilter things in weird movies. These scenes shape the droning flow of the story, as adapted by David Kajganich from Camille DeAngelis's novel, which I assume had to have more of a driving shape and more connective tissue than this. Between the hazy cinematography and the unexpectedly laconic, folk-flavored score by Trent Reznor & Atticus Ross, Bones and All feels like when you're fighting to stay awake in a moving vehicle, cradled by the lullaby of soft road noises and the land undulating as it rushes by.

This is all very rich and lush and dreamy, and honestly not very surprising or new; "lovers who commit crimes and then race through the beautiful middle-American landscape" is an old genre, and the rather unhidden theft from Terrence Malick in general makes this feel particularly like a horror-themed Badlands knock-off in ways that don't harm it, but certainly don't do it any good. Russell and Chalamet are more than credible as the young loners who find themselves increasingly desperate for each other's presence, but they're still going through pretty much exactly the arcs you would imagine, and even the cannibalism wrinkle really just means that this film's inevitable final scene that you can see coming from hours away isn't precisely the same as the inevitable final scene in a cannibal-free version of this story.

Still, the lack of apology or shame with which Guadagnino and company dive into the sweeping gothy teen pomposity of these emotions and this story makes for a very swoony and lovely experience. It is, again, all about those sensory impressions. The film is set in the 1980s, for no obvious reason than because of the particular music that can therefore be used, and the ability to give Chalamet the exact haircut and costume he gets here (he's wearing stonewashed jeans that are ripped open at the knees, and they feel more precisely-defined and tied to a certain way of life than anything else about any character in the movie). But if the film's mood needed that pre-internet, post-hippie setting to thrive in, then I'm glad they went there, because the mood really is pretty lovely. And even if Bones and All never really turns out to be more than a "vibes" movie - and at 131 minutes, a "vibes" movie that's almost taunting us to lose interest, especially given that its weakest scenes are generally backloaded - that's what this director and several of these cast members do best. At the very least, nothing else released in 2022 is doing anything very much like this, and it's quite a lovely thing to have done.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

Possibly, this is a me problem. At any rate, I found myself wishing, multiple times in Bones and All, that it would either be more of a cannibal movie or not at all a cannibal movie, but that it at any rate was the wrong amount of cannibal movie. Cannibalism here is largely used as a metaphor, about being the kind of person who doesn't fit in properly to society and gravitates towards the small handful of people you meet in the rural, conservative-ish parts of the United States who have your same kind of not-fitting-in qualities - it's walking right up to knocking on the door of queer allegory while not quite limiting itself to that reading. And that's a tough metaphor to make work, since cannibalism is also used here as the disgusting violent crime that results in the hideous, blood-soaked deaths of innocents.

Since I'm not going to get very far dwelling on any of that, let us for now set aside the cannibalism - and again, "let us set aside the cannibalism" is just not a phrase one likes to trot out in a postive review - and attend to the things that work very well. For, whatever else we might say about it, Bones and All is still a Luca Guadagnino film, and even as he's making what I think is pretty clearly his most unsuccessful feature film since his big international breakthrough with 2009's I Am Love, he's still one of our foremost sensualists. And such a worthy subject he's turning his sensualism towards this time: with Bones and All, Guadagnino joins the grand tradition of European art film directors turning their visual sensibilities towards the remarkable, grand, tacky, vibrant, flat, and above all else really fucking big North American continent. In other words, this is his "European master makes a travelogue about the U.S." movie, a genre I am always captivated by even when the results seem at least a bit unsteady on their feet.

And as far as being a travelogue, at least, I don't think Bones and All is the least bit unsteady. It's a story of a great sweeping journey from Virginia up into Indiana, back down through Kentucky and then across Missouri and Iowa to get to Minnesota, and then back a little bit, and while it's not covering nearly as much ground as it claims to - the bulk of the shooting took place in Ohio - it still captures a lot of the particular qualities of the central part of the U.S., both the warm beauty of golden hour light on wheat fields and failing small towns, and the tiresome, lonely isolation and dustiness that blankets most of the Midwest. It's a downright Days of Heaven-esque quantity of prairie sunsets that Guadagnino and cinematographer Arseni Khachaturan (who seems to have come from basically nowhere at all to suddenly collaborate with a big-name art director on his first major release) have gifted us with. And I don't even think it's just beauty for the sake of beauty, either; this film is all about the overwhelming emo Romanticism of teen outcasts in love, with each other and with life and with freedom and with The Open Road, and all that. It's damn near schmaltzy in its celebration of youthful romance, particularly in its song choices, and only the aura of horror and disgust that never quite dissipates keeps it from hitting that point.

The romantic teenage cannibal lovers in question, for the record, are Maren (Taylor Russell), around 17, and Lee (Timothée Chalamet), at least a few years older, and they're both what is named by at least one person as "eaters" - humans who have, for reasons unknown and totally unexplored, been born with a genetic abnormality that makes them need to ingest the flesh of other humans, assuming they still count as the same species. If they don't, they go a bit deranged. All of this is explained, in a halting, disordered fashion by a much older "eater", Sully, played by Mark Rylance in a portrait of warped obsession that is, at the very least, committed as hell, even if not one other thing about Bones and All is in the same register of nightmare camp as Rylance's performance. He's the first of their kind encountered by Maren after she's abandoned suddenly by her father (André Holland), who hits the inevitable point where he fears his daughter more than he loves her one morning near the start of the film. The rest of the film is very loosely structured around Maren and Lee, traveling together first out of convenience, then out of mutual attraction, then out of desperate need, encountering various cameos that generally do the most to push this back torward horror: Rylance comes back a couple more times, to increasingly diminished returns (the third and final appearance, in particular, is lousy with "look, we had to move the plot forward somehow" vibes), and we also get to spend time with Michael Stuhlbarg, fellow "sunkissed American" director David Gordon Green, Jake Horowitz, Chloë Sevigny (whose fearlessly weird performance is the closest anybody comes to matching Rylance), and best of all, Jessica Harper, continuing her lifelong record of being among the most strikingly off-kilter things in weird movies. These scenes shape the droning flow of the story, as adapted by David Kajganich from Camille DeAngelis's novel, which I assume had to have more of a driving shape and more connective tissue than this. Between the hazy cinematography and the unexpectedly laconic, folk-flavored score by Trent Reznor & Atticus Ross, Bones and All feels like when you're fighting to stay awake in a moving vehicle, cradled by the lullaby of soft road noises and the land undulating as it rushes by.

This is all very rich and lush and dreamy, and honestly not very surprising or new; "lovers who commit crimes and then race through the beautiful middle-American landscape" is an old genre, and the rather unhidden theft from Terrence Malick in general makes this feel particularly like a horror-themed Badlands knock-off in ways that don't harm it, but certainly don't do it any good. Russell and Chalamet are more than credible as the young loners who find themselves increasingly desperate for each other's presence, but they're still going through pretty much exactly the arcs you would imagine, and even the cannibalism wrinkle really just means that this film's inevitable final scene that you can see coming from hours away isn't precisely the same as the inevitable final scene in a cannibal-free version of this story.

Still, the lack of apology or shame with which Guadagnino and company dive into the sweeping gothy teen pomposity of these emotions and this story makes for a very swoony and lovely experience. It is, again, all about those sensory impressions. The film is set in the 1980s, for no obvious reason than because of the particular music that can therefore be used, and the ability to give Chalamet the exact haircut and costume he gets here (he's wearing stonewashed jeans that are ripped open at the knees, and they feel more precisely-defined and tied to a certain way of life than anything else about any character in the movie). But if the film's mood needed that pre-internet, post-hippie setting to thrive in, then I'm glad they went there, because the mood really is pretty lovely. And even if Bones and All never really turns out to be more than a "vibes" movie - and at 131 minutes, a "vibes" movie that's almost taunting us to lose interest, especially given that its weakest scenes are generally backloaded - that's what this director and several of these cast members do best. At the very least, nothing else released in 2022 is doing anything very much like this, and it's quite a lovely thing to have done.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!