Gray areas

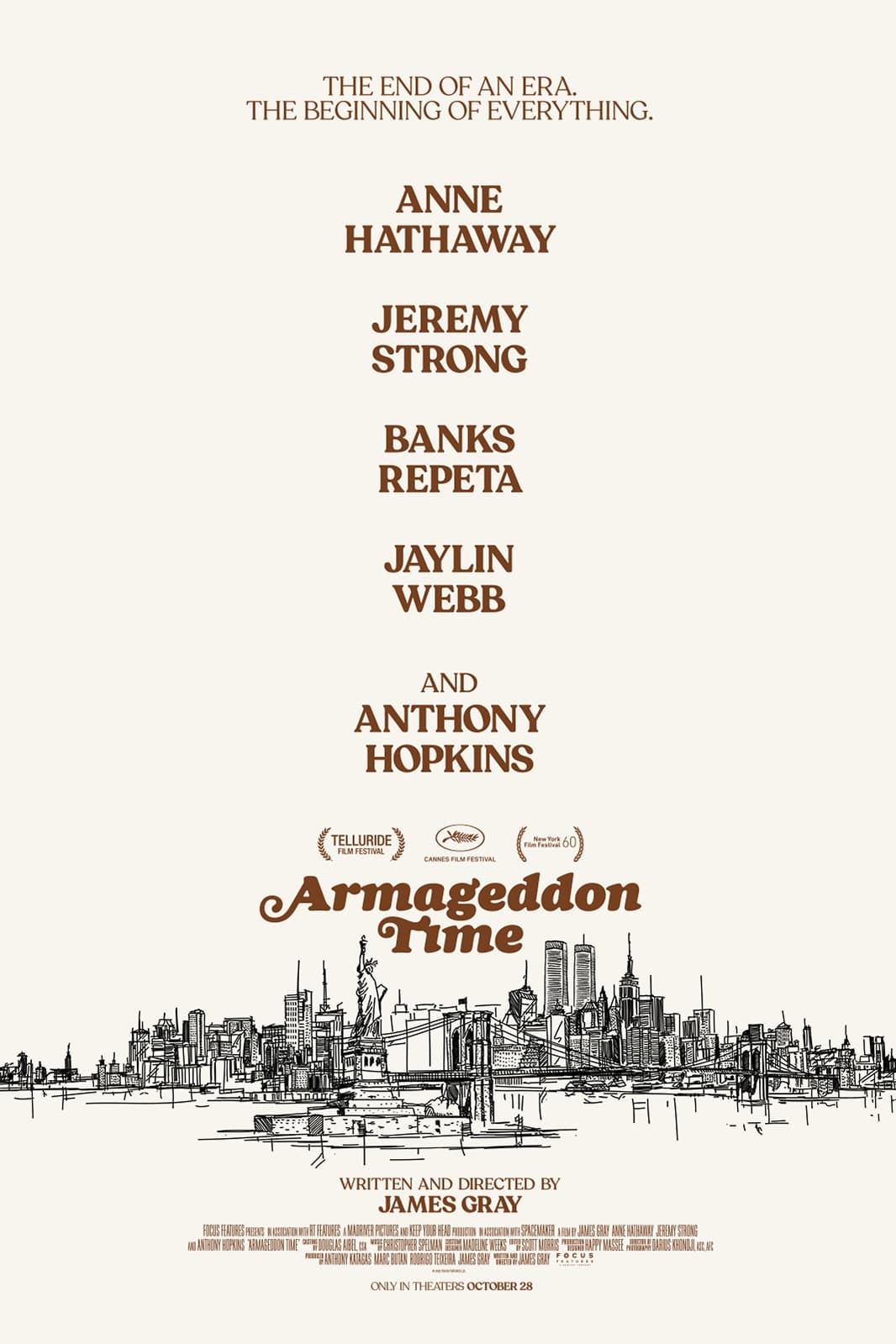

I don't think it's a good habit to get into to take account of the advertising campaign materials - part of what we call "paratexts" in the thinking-too-hard business - as part of a film review, but in the special case of Armageddon Time, I will make an exception. The film's poster, which you can see better here than in the sidebar, has a brown-on-beige color scheme to go along huge text in a typeface with slightly oblong rounded edges and puffy serifs, something like you'd expect to see on the menus for a regional chain of bar-and-grill restaurants with a name like "O'Houlihan's" or "McGillicuddy's". Coupled with the artfully deliberate scratchy look of the line drawing of the New York skyline at the bottom, the whole thing feels extremely "1970s literary fiction". And then, let us consider the actual movie itself, whose treatment of the title is entirely different: it's in white text on an all-black background, shifted heavily up and to the left, and it has been written in a generic "graffiti" typeface, like you might see on an mid-'80s hip-hop album or a late-'80s video game inviting you to prove that you are a radical dude.

That contrast, between a kind of blandly warm middlebrow sensibility and a trite in-your-face "mean streets" vibe, very much informs Armageddon Time itself, which sits at the crossroads of many things: middle class respectability politics versus lower class crudeness, the terrifying vitality of the city center versus the tidy cosiness of the more suburban experience of the outer boroughs, blue collar '70s vibes versus the gaudy consumption of the "greed is good" '80s. The very title, "Armageddon Time", more or less explicitly refers to this last one, with Armageddon being here linked to the enormous lopsided victory of Ronald Reagan in the 1980 U.S. presidential election, which the film suggests (and I agree with it) was the pivot point in American politics that created the social order that still holds sway today (e.g. there are two scenes with cameos from members of the Trump family - the two worst scenes in the film, I would say, both of them deciding that this needs to be a more explicit message movie - that essentially proclaim that Reaganism is a necessary precondition for Trumpism). And it certainly doesn't think that the way things were in 1980 or the way things are in 2022 are in any way good; the film's central thesis, with all the particulars boiled off, comes down to "things are generally terrible and even if you recognise that they are terrible, the social and economic forces weighing down on you means it is almost impossible for you to do anything as an individual to make them better; at the same time, the basic rules of morality insist that you keep trying". I think it is a pessimistic film more than a nihilistic one, but either way, it's heavy as hell and terribly thorny and ambivalent. It's not called Armageddon Time for nothing.

All that being said, what cuts against the gloominess, making for a movie that's watchable and at times deeply humane despite its cynicism, is that that this is essentially a work of nostalgia - a work of anti-nostalgia, more accurately. Either way, it finds writer-director James Gray, who was an eleven-year-old Jewish kid living in Queens in the autumn of 1980, telling the story of Paul Graff (Banks Repeta), an eleven-year-old Jewish kid living in Queens in the autumn of 1980. It starts on the first day of sixth grade, when Paul, a lazy student with a propensity for art, immediately gravitates towards Johnny (Jaylin Webb), an African-American student who was held back a year, and thus has already arrived at the new year with their teacher (Andrew Polk) ready and eager to treat him as a disruptive influence. At home, Paul is already disrupting things quite well on his own, having just hit that horrendous ugly part of adolescence where he's resentful of not having any autonomy while not being bright enough to have earned any such autonomy. And thus his days are spent openly disrespecting his mother, PTA member Esther (Anne Hathaway), and more subtly defying his father, plumber Irving (Jeremy Strong). The only family member who he much likes is his maternal grandfather, Aaron (Anthony Hopkins), a Ukrainian immigrant who is solely responsible for encouraging his artistic aspirations.

I would say that this takes the path you would most likely expect a sensitive young artist coming-of-age story to take, only to arrive at a highly unexpected destination. This is partially because Gray, unlike most filmmakers looking back at a young version of himself, doesn't put any particular energy into presenting Paul as particularly insightful, or good, or sensitive. He is kind of exactly what the adults around him take him for - a lazy underachiever - and he's sympathetic mostly on the grounds that even lazy underachievers deserve happy lives. But of course the film's main point is that desert has nothing to do with anything, and that's what the coming-of-age arc is depicting: not the gaining of maturity, nor of wisdom, but of a horrified realisation that functioning as an adult in an unfair world is largely a matter of deciding what moral precepts you can afford to ignore on a moment-by-moment basis. And that unfairness cuts both ways: Paul is just as disgusted to learn about his unearned privileges and good fortune as he is by the things that make him powerless or victimised: his age, his religion.

The film's ambivalence to all this is never about what is morally righteous; indeed, Armageddon Time is a very morally outraged film, looking at racial injustice with cold fury and presenting Fred Trump (John Diehl) as black-eyed, oil-slicked goblin. The ambivalence is about what to do with this knowledge, something that it ahpproaches entirely through the eyes of its awkward and confused protagonist, young enough to need the comforting certainty of absolutes and binaries, and thus subjected to deep pain when he finds all the adults around him are in some sense corrupted by the desire to hang on to the comfortable class positions they so tenaciously fought for as unwanted immigrants and the children of unwanted immigrants.

This is all packaged in the body of a well-observed memory piece about a very particular culture in a very particular place at a very particular time. Gray has noted that after making a pair of big fancy studio genre films, 2016's The Lost City of Z and 2019's Ad Astra, he wanted to go back to basics with something small and character-based and domestic, and it's hard to imagine what could fit the bill better than a story about his own childhood, set in such a distinctly realised setting. Armageddon Time is full to the brim with scenes that feel so precise and idiosyncratic that they could only come from a deep intimacy, knowledge of the characters and their behavior that's specific in the littlest ways. There's a phenomenal dinner scene early on that sets up an extended family dynamic so perfectly that it's almost uncomfortably real: the way that certain characters talk over each other in ways that very obviously started long before this meal, and only reflects these exact interpersonal relationships; there's a pitched battle around Chinese food that's as much about being or not being the kind of people that can afford to waste food as it is about parents and children fighting over the rules.

The writing is precise and so is the construction of this world by production designer Happy Massee and costume designer Madeline Weeks, evoking not just the late '70s in general, but a specific kind of slightly worn-out version of it, the kind of house where everything is nice but a little out of date. It's not just good at evoking the specific family we're viewing, but the exhaustion and the sense of things wearing down and reaching the breaking point suggested by the film's title, it's morose diagnosis of society, its soft autumn cinematography by Darius Khondji, representing everything in drab period-appropriate browns that also feels as much about creating a desiccated mood as it is about realism. Armageddon Time is a tired film, and not at all a hopeful one about things getting less tired, and the visuals reflect tha. But it also very much about people, where they live and how, and as much as the film looks worn-out, there's also a clear and rich understanding of who these characters are and why even in their flaws and shortcomings, they matter. Browns can be warm, too, after all, and that tension between moodiness and warmth is a remarkable blend that makes for an incredible complicated and satisfying viewing experience.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

That contrast, between a kind of blandly warm middlebrow sensibility and a trite in-your-face "mean streets" vibe, very much informs Armageddon Time itself, which sits at the crossroads of many things: middle class respectability politics versus lower class crudeness, the terrifying vitality of the city center versus the tidy cosiness of the more suburban experience of the outer boroughs, blue collar '70s vibes versus the gaudy consumption of the "greed is good" '80s. The very title, "Armageddon Time", more or less explicitly refers to this last one, with Armageddon being here linked to the enormous lopsided victory of Ronald Reagan in the 1980 U.S. presidential election, which the film suggests (and I agree with it) was the pivot point in American politics that created the social order that still holds sway today (e.g. there are two scenes with cameos from members of the Trump family - the two worst scenes in the film, I would say, both of them deciding that this needs to be a more explicit message movie - that essentially proclaim that Reaganism is a necessary precondition for Trumpism). And it certainly doesn't think that the way things were in 1980 or the way things are in 2022 are in any way good; the film's central thesis, with all the particulars boiled off, comes down to "things are generally terrible and even if you recognise that they are terrible, the social and economic forces weighing down on you means it is almost impossible for you to do anything as an individual to make them better; at the same time, the basic rules of morality insist that you keep trying". I think it is a pessimistic film more than a nihilistic one, but either way, it's heavy as hell and terribly thorny and ambivalent. It's not called Armageddon Time for nothing.

All that being said, what cuts against the gloominess, making for a movie that's watchable and at times deeply humane despite its cynicism, is that that this is essentially a work of nostalgia - a work of anti-nostalgia, more accurately. Either way, it finds writer-director James Gray, who was an eleven-year-old Jewish kid living in Queens in the autumn of 1980, telling the story of Paul Graff (Banks Repeta), an eleven-year-old Jewish kid living in Queens in the autumn of 1980. It starts on the first day of sixth grade, when Paul, a lazy student with a propensity for art, immediately gravitates towards Johnny (Jaylin Webb), an African-American student who was held back a year, and thus has already arrived at the new year with their teacher (Andrew Polk) ready and eager to treat him as a disruptive influence. At home, Paul is already disrupting things quite well on his own, having just hit that horrendous ugly part of adolescence where he's resentful of not having any autonomy while not being bright enough to have earned any such autonomy. And thus his days are spent openly disrespecting his mother, PTA member Esther (Anne Hathaway), and more subtly defying his father, plumber Irving (Jeremy Strong). The only family member who he much likes is his maternal grandfather, Aaron (Anthony Hopkins), a Ukrainian immigrant who is solely responsible for encouraging his artistic aspirations.

I would say that this takes the path you would most likely expect a sensitive young artist coming-of-age story to take, only to arrive at a highly unexpected destination. This is partially because Gray, unlike most filmmakers looking back at a young version of himself, doesn't put any particular energy into presenting Paul as particularly insightful, or good, or sensitive. He is kind of exactly what the adults around him take him for - a lazy underachiever - and he's sympathetic mostly on the grounds that even lazy underachievers deserve happy lives. But of course the film's main point is that desert has nothing to do with anything, and that's what the coming-of-age arc is depicting: not the gaining of maturity, nor of wisdom, but of a horrified realisation that functioning as an adult in an unfair world is largely a matter of deciding what moral precepts you can afford to ignore on a moment-by-moment basis. And that unfairness cuts both ways: Paul is just as disgusted to learn about his unearned privileges and good fortune as he is by the things that make him powerless or victimised: his age, his religion.

The film's ambivalence to all this is never about what is morally righteous; indeed, Armageddon Time is a very morally outraged film, looking at racial injustice with cold fury and presenting Fred Trump (John Diehl) as black-eyed, oil-slicked goblin. The ambivalence is about what to do with this knowledge, something that it ahpproaches entirely through the eyes of its awkward and confused protagonist, young enough to need the comforting certainty of absolutes and binaries, and thus subjected to deep pain when he finds all the adults around him are in some sense corrupted by the desire to hang on to the comfortable class positions they so tenaciously fought for as unwanted immigrants and the children of unwanted immigrants.

This is all packaged in the body of a well-observed memory piece about a very particular culture in a very particular place at a very particular time. Gray has noted that after making a pair of big fancy studio genre films, 2016's The Lost City of Z and 2019's Ad Astra, he wanted to go back to basics with something small and character-based and domestic, and it's hard to imagine what could fit the bill better than a story about his own childhood, set in such a distinctly realised setting. Armageddon Time is full to the brim with scenes that feel so precise and idiosyncratic that they could only come from a deep intimacy, knowledge of the characters and their behavior that's specific in the littlest ways. There's a phenomenal dinner scene early on that sets up an extended family dynamic so perfectly that it's almost uncomfortably real: the way that certain characters talk over each other in ways that very obviously started long before this meal, and only reflects these exact interpersonal relationships; there's a pitched battle around Chinese food that's as much about being or not being the kind of people that can afford to waste food as it is about parents and children fighting over the rules.

The writing is precise and so is the construction of this world by production designer Happy Massee and costume designer Madeline Weeks, evoking not just the late '70s in general, but a specific kind of slightly worn-out version of it, the kind of house where everything is nice but a little out of date. It's not just good at evoking the specific family we're viewing, but the exhaustion and the sense of things wearing down and reaching the breaking point suggested by the film's title, it's morose diagnosis of society, its soft autumn cinematography by Darius Khondji, representing everything in drab period-appropriate browns that also feels as much about creating a desiccated mood as it is about realism. Armageddon Time is a tired film, and not at all a hopeful one about things getting less tired, and the visuals reflect tha. But it also very much about people, where they live and how, and as much as the film looks worn-out, there's also a clear and rich understanding of who these characters are and why even in their flaws and shortcomings, they matter. Browns can be warm, too, after all, and that tension between moodiness and warmth is a remarkable blend that makes for an incredible complicated and satisfying viewing experience.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!