Mathieu Amalric has spent the past three decades forging a career that American moviegoers have experienced in concentrically different subsets. For the widest circle, he was the memorably odd villain in Quantum of Solace, and has occasionally played small supporting roles in Wes Anderson films (The Grand Budapest Hotel; The French Dispatch of the Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun); those folks might also have seen him as the mostly immobile lead in the Oscar-nominated The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, or remember him as a key informant in Spielberg’s Munich, or have appreciated his unexpectedly compassionate presence during Sound of Metal’s home stretch. Then you’ve got the smaller but still robust cinephile circle, for whom Amalric burst onto the scene as Arnaud Desplechin’s eccentric muse in My Sex Life…or How I Got Into an Argument, way back in 1996, and has seemingly appeared in every third French movie released in U.S. arthouses ever since. Relatively few Americans, however, have followed Amalric’s considerable work behind the camera. He’s directed six features to date—eight, if you include a couple of projects made for French television—and none of them has made much of a splash on these shores; the most notable is probably 2010’s On Tour, which played in Competition at Cannes that year and had the commercial benefit of being about burlesque strippers.

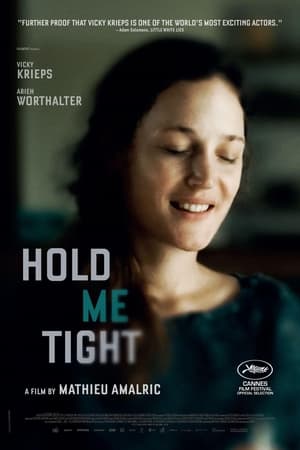

I don’t know that Amalric’s latest effort, Hold Me Tight, has changed that, or is likely to do so, though it should. For one thing, it’s built around the strongest Vicky Krieps performance that I’ve seen since Phantom Thread made her an instant star (by arthouse standards, at least); Krieps’ 2022 awards buzz will almost certainly be for her Empress Elisabeth of Austria in the forthcoming costume drama Corsage (due for release at Christmas), but this is by far the more demanding and thorny role. For another, it’s got a gimmick, sort of, though I don’t imagine that Amalric would appreciate his movie’s singular formal/narrative strategy being described as such. Hold Me Tight presents a challenge to the honorable-minded critic: You can’t tackle the film in any depth without revealing the ways in which it deliberately misleads viewers for a good long while, and being kept off balance is crucial to the experience. I do note that its IMDb logline cops to some ambiguity, describing the plot thusly: “A woman one day simply walks out on her family. Or does she?” So maybe there’s no point in dancing around the matter. Just know that the next few paragraphs are gonna necessarily lay some stuff out, and you might be better off seeing the film before reading on.

Anyway, it definitely does look, at the outset, as if Clarisse (Krieps) has snuck out of her house at the break of dawn, leaving behind her husband, Marc (Arieh Worthalter), and their two pre-adolescent children, Lucie (Anne-Sophie Bowen Chatet) and Paul (Sacha Ardilly). We don’t know why she’s bailing, and the others seem largely unfazed by her absence; Amalric jaggedly cuts back and forth between Clarisse’s journey—she’s driving along the coast, aimlessly—and scenes of mundane domestic activity back home. Lucie’s been learning the piano, and is still at the painfully-plunking-out-“Für-Elise”-one-note-at-a-time stage, though she seems to markedly improve in relatively short order. It’s hard to tell, really, because space-time itself has an unstable quality throughout the entire film, with events that are clearly separate nonetheless bleeding into each other. Clarisse’s voice sometimes appears on the soundtrack, as a loving murmur, in scenes at the house she left, and her family sometimes responds to her as if she were present rather than disembodied. Meanwhile, in what passes for objective reality, Clarisse frequently looks distraught, at one point burying her face in the crushed ice surrounding fish at an outdoor market. And she occasionally says cryptic things like “You know, I see them” (with no antecedent to “them”), or desperately hugs a total stranger at a bar, calling him Marc.

To Amalric’s credit, he doesn’t play this disorienting game to the end, and declines to reserve what’s going on for a climactic twist. About 30 minutes into Hold Me Tight, a flashback (or a memory, more accurately) makes it pretty clear that Clarisse’s husband and kids are dead, having been engulfed by an avalanche during a skiing vacation in Spain at which Mom, for reasons that are never quite explained, wasn’t present. (Seems as if she’d planned to meet them later.) Their bodies weren’t immediately recoverable, due to weather conditions, and the film takes place during the roughly two months between the tragic accident and the spring thaw, during which period Clarisse mentally constructs an elaborate fantasy world in which she left home and her family survived. To some extent, she can manipulate their behavior at will…but her will wavers, and comfort keeps being infected by guilt. I feel a bit sheepish about making this comparison, but Hold Me Tight plays very much like WandaVision if Wanda Maximoff possessed no powers of any kind—just a grief-wracked imagination. While there aren’t any sitcom parodies, the movie does have a goofy sense of humor, at times, despite the heavy subject matter. Clarisse imagines Lucie gradually becoming a piano prodigy, even as she stalks a real-life teenage piano student (Juliette Benveniste) who reminds her of Lucie and so becomes teen Lucie in her vision; after Clarisse sees part of a documentary about Argentine pianist Martha Argerich, this mental projection of Lucie, though still in the form of the random piano student, suddenly sports Argerich’s flowing snow-white mane of hair.

Amalric adapted his script from a stage play by Claudine Galea (originally titled Je reviens de loin, or I Return From Afar), but you’d never intuit a theatrical origin, given how aggressively the film obliterates conventional borders between reality and fantasy via purely cinematic means. It’s rarely possible to feel confident that what you’re watching is actually happening, or happened at some point in the past; at best, you can rule certain things out, be confident that they’re wholly invented. Krieps’ task is to keep this chaotic formal exercise rooted in Clarisse’s emotional turbulence, and she does a remarkable job of conveying the amalgam of joy and anguish, pride and regret, that her chosen alternate life entails. What she doesn’t convey—and this cripples the movie to a large extent, if you ask me, though I can appreciate the argument that we’re meant to grapple with it—is why Clarisse can only resuscitate her family by removing herself from the household, except as a sort of benevolent spirit who visits now and again. It’s not as if she’s volunteering to die in their place, as her vision very specifically has her abandon them without explanation; she even imagines Lucie writing diary entries to her mother, asking her where she’s gone and when she’ll be back. Nor, unless I missed something, can their death be attributed to her presence in their lives, such that they’d still be alive had she walked out a month before the accident. Whether that’s even something that she might have considered remains unaddressed. Was she unhappy? Was Marc? Hold Me Tight remains vague in enough crucial respects that it fails to amass real power, and that’s exacerbated by extended scenes in the film’s latter half during which it’s difficult to get invested in lives that we now know perfectly well are just a grieving woman’s sorrowful projection. Still, it’s an arresting use of the medium, and by rights should firmly establish Amalric, at long last (he directed his first feature in 1997), as more than just a strangely intense-looking face.

One of the first notable online film critics, having launched his site The Man Who Viewed Too Much in 1995, Mike D’Angelo has also written professionally for Entertainment Weekly, Time Out New York, The Village Voice, Esquire, Las Vegas Weekly, and The A.V. Club, among other publications. He’s been a member of the New York Film Critics Circle and currently blathers opinions almost daily on Patreon.