Consider this a high compliment: It would have taken me quite some time, had I not been aware of the fact in advance, to recognize All That Breathes as a documentary. The film’s first shot consists of a lengthy, slow track across a nighttime landscape in an as-yet-unidentified locale—one that appears to be urban or suburban, judging from lights and cars visible out of focus in the distance. The foreground’s a wasteland, however, strewn with refuse, and as the camera moves downward (while still traveling left to right), we see that it’s also swarming with rats. What’s notable about this introduction to All That Breathes’ world…well, two things are notable, really. One is that the shot has only a tangential relationship to director Shaunak Sen’s actual subject, and said tangent won’t be clearly evident for a while. (It takes some time even for the subject to resolve itself.) More than that, though, the camera’s study of several dozen rats crawling through what could easily be a post-apocalyptic setting comes across less horrified or alarmist (though that’s in fact the rhetorical intent) than simply curious. Fascinated. Awestruck, even. It’s the product of an aesthetic impulse, not an expository one, which is why I’d very likely have mistaken All That Breathes for a fictional narrative, absent foreknowledge. And Sen’s privileging of the sensory over the purely informative remains constant throughout.

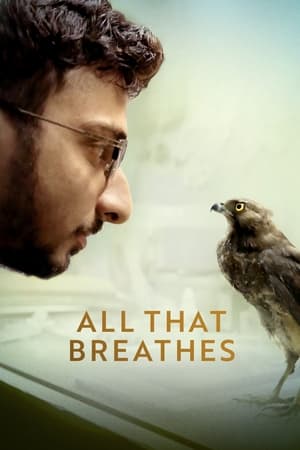

All the same, he did initially set out to profile two brothers, Mohammad Saud and Nadeem Shehzad (it’s unclear to me why they have different surnames; everyone onscreen calls the former “Saud”), and their joint organization, Wildlife Rescue. For the past two decades, Saud and Nadeem, who live in New Delhi, have devoted much of their lives to caring for wounded and sick birds of prey, with a particular emphasis on the black kite. Well, “particular emphasis” in the sense that there are approximately a million billion zillion black kites in India—they’re reportedly perceived locally much the way that Americans view pigeons—and they hence make up a hefty percentage of the birds requiring medical intervention. All That Breathes being the kind of film that it is, we don’t learn a great deal about how Wildlife Rescue operates, even as we watch the brothers patiently do their work; references are made, in casual conversation (rarely does anyone so much as visually acknowledge the camera, much less directly address it), to a business that involves making soap dispensers, and at one point Sen slowly pans from the basement room where Saud and Nadeem bandage kites over to another large basement room where unidentified other people seem to be performing manual labor of some sort, most likely making the dispensers. Again, though, such details aren’t this movie’s top priority.

Instead, Sen uses his ostensible subject mostly as an excuse to capture whatever interests him. Sometimes that’s the interaction between Saud, Nadeem, and their slightly befuddled employee Salik; these are thoughtful, articulate men, and random topics of conversation include such questions as whether there could ever be enough water on Earth to submerge all land (as in Waterworld, though they don’t expressly mention that) and whether kites would or even could eat their corpses following a nuclear war. The latter morbidity comes up due to tension with Pakistan, and there’s also an undercurrent of fear, for this Muslim family, regarding nearby sectarian violence, though that’s primarily conveyed via news reports playing on radios and TV sets. But while the film notes that this stuff is happening, it doesn’t dwell on either politics or psychology, and Sen’s camera constantly gets distracted by the natural world—not just birds (though there are many shots of raptors staring into the lens with the discomfitingly defiant glare of a Sergio Leone villain), but lizards crawling on walls, mosquitos drinking from stagnant pools, monkeys traversing the superstructure of a building complex. Reflections in water are a favorite: one cityscape shot looks oddly distorted for reasons that are hard to pinpoint until ripples give it away, and another watches a centipede (or millipede; I didn’t count) crawling across what looks like a tarp (with twitter.com printed on it, weirdly), avoiding small puddles that have formed in the wrinkled material’s indentations, until suddenly we see an airplane sail across the largest puddle’s mirrored surface.

All That Breathes does eventually start developing a thesis statement, one that circles back to its rat-infested opening shot: New Delhi suffers from all of the problems that beset major metropolitan areas, and animals suffer the worst of it. One of the brothers points out that kites are adapting, in troubling ways, to humanity’s dominance: He keeps finding cigarette butts in the birds’ enclosures, and determines that the birds are bringing them in order to repel parasites. “Think of the city as a stomach,” says Nadeem, “and the kites are like the microbiome of a gut.” As its title suggests, the film (or at least its “protagonists”) insist that every form of animal life has value…though, at the same time, Nadeem thinks Saud and Salik are out of their minds when they swim across a freezing-cold river to rescue a wounded kite on the other side, and he refuses to help out. When you’re watching a stubborn dude alternately yell instructions and insults at his two colleagues, it’s hard to see the film as a noble tract.

One arguably disingenuous aspect of the environmental argument bothers me. All That Breathes repeatedly refers to birds just falling out of the sky in droves of late. It also makes repeated references to New Delhi’s nightmarish air quality—the family even has a monitor that tells them when it’s safe for kids to play outside, telling one little boy that he’ll have to wait until the needle moves out of the red. And it pretty clearly—to my mind, at least—encourages non-Indian viewers to connect those two things, even though it never explicitly says that pollution is sickening the kites. Jumping to that conclusion couldn’t be more natural, and I only learned otherwise because we see a New York Times article about Wildlife Rescue (published in February 2020) framed on the brothers’ basement wall. Reading that afterward, I was surprised to learn that most of the kites treated by Saud and Nadeem have in fact been injured by…other kites. Not other birds, mind you. The kind of kites that little kids fly. Indian kites, it turns out, often have threads that are coated with colorful crushed glass, which means that Indian birds are flying through a sky that’s more or less festooned with barbed wire. We do see some of those non-avian kites in the movie, cluttering the voids between buildings, and no doubt Indian audiences draw the correct conclusion immediately, assuming that they weren’t already aware. But the film really kind of goes out of its way—even for something so anti-expository—not to make that clear to anyone else.

It's a forgivable lapse, though, because All That Breathes (even the title seems to be nudging us toward blaming pollution!) ultimately isn’t all that invested in being a polemic. Sen seeks out serendipity, and gets amply rewarded by such incredible moments as one in which Salik has his eyeglasses stolen right off of his face by a kite that unexpectedly swoops in from behind him while he’s busy feeding another kite atop the building’s roof. This happens so quickly that it almost looks as if Salik’s glasses were digitally removed from the shot, and while the incident doesn’t “go anywhere,” save for one subsequent scene that sees Saud and Nadeem tell Salik to please shut up about his damn glasses already, it’s much more central to the film’s modus operandi than any of the pleas (low-key though even those are) for more compassion toward every living creature, regardless of religion or species. I should belatedly confess that, even as an animal lover, my interest in a straightforward documentary about two guys saving birds would have been fairly low; if that’s the film you’d prefer to see, All That Breathes might not be wholly satisfying. For those who gravitate toward unconventional, visually arresting docs, however, here’s one that shouldn’t be missed.

One of the first notable online film critics, having launched his site The Man Who Viewed Too Much in 1995, Mike D’Angelo has also written professionally for Entertainment Weekly, Time Out New York, The Village Voice, Esquire, Las Vegas Weekly, and The A.V. Club, among other publications. He’s been a member of the New York Film Critics Circle and currently blathers opinions almost daily on Patreon.