It's in the nature of adolescence to rebel—against your parents, against your background, against anything that defines you in a way that doesn't match your evolving self-image. Every coming-of-age story sees its protagonist reject the status quo and seek out something unfamiliar and/or expressly forbidden. Some go further than others, though, and Funny Pages—the directorial debut of Owen Kline, previously best known for playing the compulsively masturbating younger brother in Noah Baumbach's semi-autobiographical The Squid and the Whale—means to poke good-natured fun at a comfortably middle-class kid who mistakes scuzziness for authenticity. It's an inspired idea, but Kline (whose own background, as the son of Phoebe Cates and Oscar-winner Kevin Kline, is decidedly on the ritzy side) takes the most mealy-mouthed angle on it imaginable, leaning hard on eccentricity for its own sake and declining to follow through on the thorniest questions he raises. Never before have I seen a film so afraid of where it's heading that it just stops cold with what seems like at least another 30 minutes left to go, counting on obliging viewers to fill in the blanks.

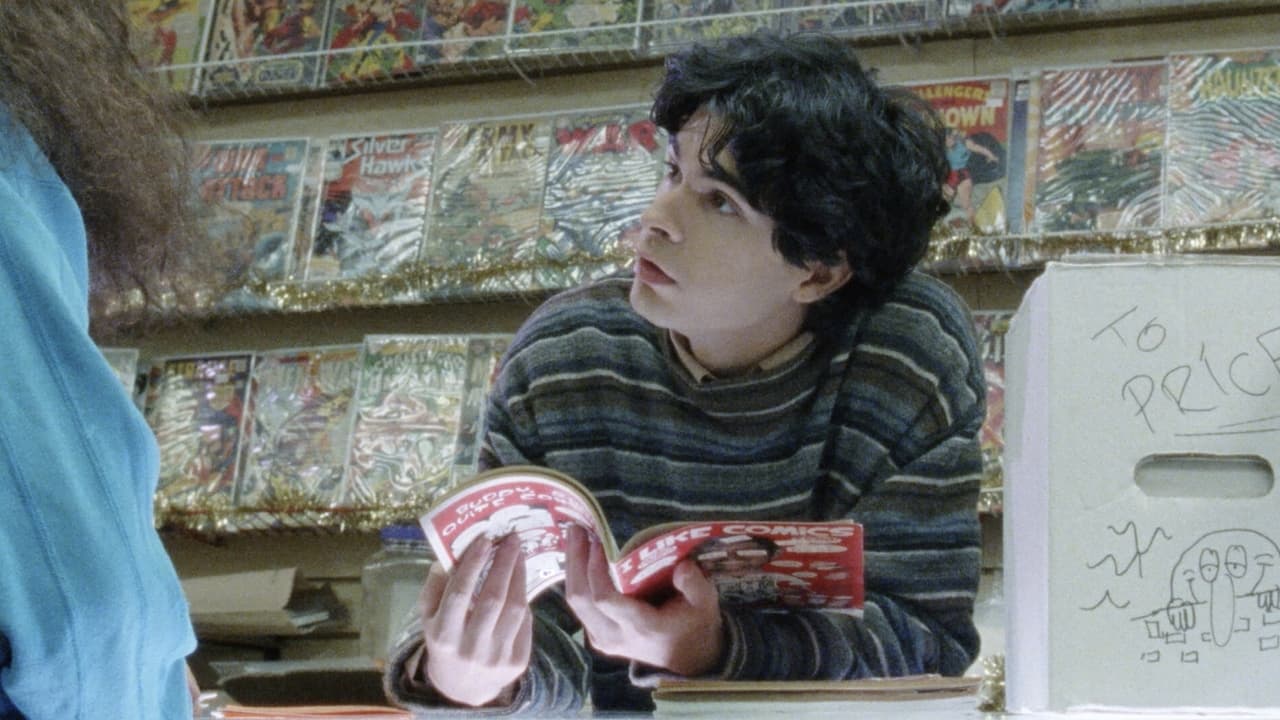

Which is not to say that Funny Pages gets off to a terrific start, either. We first meet teenage aspiring underground cartoonist Robert (Daniel Zolghardi, previously seen as the kid who initiates a creepy Truth or Dare game with Kayla in Eighth Grade) in conference with his favorite teacher, Mr. Katano (Stephen Adly Guirgis), who tells the boy that he's already doing professional-level work. In the first of many less-than-credible developments, Mr. Katano then volunteers to serve as Robert's life-drawing model for his portfolio, stripping naked right there in the classroom; this moment is more about pushing Robert to embrace the unconventional (Guirgis is quite obese) than about suggesting that a line's been crossed, but it still feels weirdly reckless, as if Kline is randomly pushing buttons without having thought very much about their function. (It's also unclear when the film takes place—hard to imagine any teacher, however contemptuous of propriety, risking that move today. The absence of smartphones combined with the presence of laptops suggests maybe 2006, when Kline would have been 15.) A series of unlikely events lands Robert in minor legal trouble, following which he informs his parents (Maria Dizzia and Josh Pais) that he won't be going to college and will be moving out of the house immediately, in search of the artist's proper path.

This turns out to entail renting half of a room in Trenton, NJ's creepiest basement apartment. In some respects, Funny Pages seems designed as a rebuke of sorts to Terry Zwigoff's Ghost World (adapted from Daniel Clowes' graphic novel), which likewise focused on a middle-class teen malcontent with artistic aspirations who yearns to leave the nest. Like Enid, who celebrates the creeps and losers and weirdos ("Those are our people," she insists to her more upwardly mobile best friend, played by Scarlett Johansson), Robert longs to join the badass clique of society's outcasts; what he actually encounters is an endless procession of odd-looking, socially awkward individuals, each one reduced to the sum of his (it's mostly men) alarming idiosyncrasies. For example, Barry (Michael Townsend Wright), the middle-aged man into whose dangerously cluttered, oppressively humid subterranean crawl space Robert moves, has several unsightly strands of hair permanently plastered across his sweaty forehead and spends his spare time filing down his horny toenails; nothing about him is remotely cool (or particularly funny, though these scenes are clearly aiming at cringe comedy)—he's just a discomfiting vision of Robert's potential future. Even Robert's best friend and fellow comix enthusiast, Miles (Miles Emanuel), sports facial acne so extensive that it's practically the only thing about him that registers. Everything's designed to create stark contrasts, making Robert's desire to be different look increasingly misguided.

Again, I admire this seemingly reactionary stance in theory, if only because it's a refreshing antidote to the countless indie films about following your dreams down whatever offbeat path they may occupy. Kline can't get the tonal balance right, however, and Funny Pages permanently loses its way after introducing Wallace (Matthew Maher), a singularly strange man upon whom Robert fixates for the dumbest possible reason. Many years ago, Wallace had worked as a color separator for one of Robert's favorite comic-book publishers; that's a job requiring no artistic ability whatsoever (as Wallace himself repeatedly notes)—it's been described as akin to bagging groceries—but Robert perceives any connection to the comix world, however marginal, as pure gold. Maher, a fine character actor who's worked steadily since the late '90s without ever landing a role this prominent, gives a memorably intense performance, but the relationship never feels remotely credible, even acknowledging Robert's desperate need for a connection. If you want to be the next Cassavetes, somebody who once wrote press releases for Miramax (and is currently embroiled in a legal dispute for assaulting a pharmacist) will not strike you as the ideal person to teach you mise-en-scène.

At practically every turn, Kline exaggerates what might have been insights into idiocies. Wallace asking Robert to goad the aforementioned pharmacist into violence (thereby "proving" that he's easily provoked) sets up an intriguing, potentially uproarious scenario that could unfold in any number of ways; for some reason, Funny Pages has Robert panic and physically assault the pharmacist himself—an action that's somehow triggered by an elderly woman begging Robert to buy her some Percocet. Goofy, to be sure, but it neither deepens nor clarifies the film's ostensible theme, coming across primarily as an excuse to give Louise Lasser her first notable film role since 2000's Requiem for a Dream. The figurative cartoonishness culminates in a ludicrous high-decibel setpiece that sees Robert invite Wallace to his family's house on Christmas morning (without any advance notice), resulting in a shattered bathroom window, a car smashed into the closed garage door, and another physical assault. "You're obsessed with my failure!" Wallace angrily yells at one point, and he's not wrong...but he could just as easily be addressing that to the film's director.

This blowup occurs about 80 minutes into Funny Pages, and perfectly exemplifies what every screenwriting manual lays out as the pivot from act two into act three. If you paused the film there and asked viewers how much time remains, virtually every guess would fall somewhere between 15 and 30 minutes. Instead, it just ends. Or, rather, it doesn't just end: Kline superimposes the (cutely handwritten) closing credits over a lengthy shot of Robert staring silently into space, his expression difficult to parse. Michael Clayton pulled off more or less the same ambiguous ending, but only because writer-director Tony Gilroy had shepherded us there in a way that made it possible to imagine, with impressive specificity, what George Clooney's character might be thinking. Here, the prolonged gaze feels like indolence at best, sheer cowardice at worst. Is Robert reflecting upon the wisdom of his recent decisions? Is he reassessing his career path? Is he experiencing some greater existential crisis still? Or is he merely resolute and temporarily numb in the immediate aftermath of what was really pretty significant insanity? We haven't learned enough about this kid to draw even the most tenuous of conclusions. That Ghost World so skillfully accomplishes everything that Funny Pages whiffs—inventing a reluctant mentor (Steve Buscemi's Seymour, who wasn't in the graphic novel) who's screwed up in realistic, non-exploitative ways; ending on an uncertain note that's fully earned—only makes this phantom world seem all the more phony.

One of the first notable online film critics, having launched his site The Man Who Viewed Too Much in 1995, Mike D’Angelo has also written professionally for Entertainment Weekly, Time Out New York, The Village Voice, Esquire, Las Vegas Weekly, and The A.V. Club, among other publications. He’s been a member of the New York Film Critics Circle and currently blathers opinions almost daily on Patreon.

Which is not to say that Funny Pages gets off to a terrific start, either. We first meet teenage aspiring underground cartoonist Robert (Daniel Zolghardi, previously seen as the kid who initiates a creepy Truth or Dare game with Kayla in Eighth Grade) in conference with his favorite teacher, Mr. Katano (Stephen Adly Guirgis), who tells the boy that he's already doing professional-level work. In the first of many less-than-credible developments, Mr. Katano then volunteers to serve as Robert's life-drawing model for his portfolio, stripping naked right there in the classroom; this moment is more about pushing Robert to embrace the unconventional (Guirgis is quite obese) than about suggesting that a line's been crossed, but it still feels weirdly reckless, as if Kline is randomly pushing buttons without having thought very much about their function. (It's also unclear when the film takes place—hard to imagine any teacher, however contemptuous of propriety, risking that move today. The absence of smartphones combined with the presence of laptops suggests maybe 2006, when Kline would have been 15.) A series of unlikely events lands Robert in minor legal trouble, following which he informs his parents (Maria Dizzia and Josh Pais) that he won't be going to college and will be moving out of the house immediately, in search of the artist's proper path.

This turns out to entail renting half of a room in Trenton, NJ's creepiest basement apartment. In some respects, Funny Pages seems designed as a rebuke of sorts to Terry Zwigoff's Ghost World (adapted from Daniel Clowes' graphic novel), which likewise focused on a middle-class teen malcontent with artistic aspirations who yearns to leave the nest. Like Enid, who celebrates the creeps and losers and weirdos ("Those are our people," she insists to her more upwardly mobile best friend, played by Scarlett Johansson), Robert longs to join the badass clique of society's outcasts; what he actually encounters is an endless procession of odd-looking, socially awkward individuals, each one reduced to the sum of his (it's mostly men) alarming idiosyncrasies. For example, Barry (Michael Townsend Wright), the middle-aged man into whose dangerously cluttered, oppressively humid subterranean crawl space Robert moves, has several unsightly strands of hair permanently plastered across his sweaty forehead and spends his spare time filing down his horny toenails; nothing about him is remotely cool (or particularly funny, though these scenes are clearly aiming at cringe comedy)—he's just a discomfiting vision of Robert's potential future. Even Robert's best friend and fellow comix enthusiast, Miles (Miles Emanuel), sports facial acne so extensive that it's practically the only thing about him that registers. Everything's designed to create stark contrasts, making Robert's desire to be different look increasingly misguided.

Again, I admire this seemingly reactionary stance in theory, if only because it's a refreshing antidote to the countless indie films about following your dreams down whatever offbeat path they may occupy. Kline can't get the tonal balance right, however, and Funny Pages permanently loses its way after introducing Wallace (Matthew Maher), a singularly strange man upon whom Robert fixates for the dumbest possible reason. Many years ago, Wallace had worked as a color separator for one of Robert's favorite comic-book publishers; that's a job requiring no artistic ability whatsoever (as Wallace himself repeatedly notes)—it's been described as akin to bagging groceries—but Robert perceives any connection to the comix world, however marginal, as pure gold. Maher, a fine character actor who's worked steadily since the late '90s without ever landing a role this prominent, gives a memorably intense performance, but the relationship never feels remotely credible, even acknowledging Robert's desperate need for a connection. If you want to be the next Cassavetes, somebody who once wrote press releases for Miramax (and is currently embroiled in a legal dispute for assaulting a pharmacist) will not strike you as the ideal person to teach you mise-en-scène.

At practically every turn, Kline exaggerates what might have been insights into idiocies. Wallace asking Robert to goad the aforementioned pharmacist into violence (thereby "proving" that he's easily provoked) sets up an intriguing, potentially uproarious scenario that could unfold in any number of ways; for some reason, Funny Pages has Robert panic and physically assault the pharmacist himself—an action that's somehow triggered by an elderly woman begging Robert to buy her some Percocet. Goofy, to be sure, but it neither deepens nor clarifies the film's ostensible theme, coming across primarily as an excuse to give Louise Lasser her first notable film role since 2000's Requiem for a Dream. The figurative cartoonishness culminates in a ludicrous high-decibel setpiece that sees Robert invite Wallace to his family's house on Christmas morning (without any advance notice), resulting in a shattered bathroom window, a car smashed into the closed garage door, and another physical assault. "You're obsessed with my failure!" Wallace angrily yells at one point, and he's not wrong...but he could just as easily be addressing that to the film's director.

This blowup occurs about 80 minutes into Funny Pages, and perfectly exemplifies what every screenwriting manual lays out as the pivot from act two into act three. If you paused the film there and asked viewers how much time remains, virtually every guess would fall somewhere between 15 and 30 minutes. Instead, it just ends. Or, rather, it doesn't just end: Kline superimposes the (cutely handwritten) closing credits over a lengthy shot of Robert staring silently into space, his expression difficult to parse. Michael Clayton pulled off more or less the same ambiguous ending, but only because writer-director Tony Gilroy had shepherded us there in a way that made it possible to imagine, with impressive specificity, what George Clooney's character might be thinking. Here, the prolonged gaze feels like indolence at best, sheer cowardice at worst. Is Robert reflecting upon the wisdom of his recent decisions? Is he reassessing his career path? Is he experiencing some greater existential crisis still? Or is he merely resolute and temporarily numb in the immediate aftermath of what was really pretty significant insanity? We haven't learned enough about this kid to draw even the most tenuous of conclusions. That Ghost World so skillfully accomplishes everything that Funny Pages whiffs—inventing a reluctant mentor (Steve Buscemi's Seymour, who wasn't in the graphic novel) who's screwed up in realistic, non-exploitative ways; ending on an uncertain note that's fully earned—only makes this phantom world seem all the more phony.

One of the first notable online film critics, having launched his site The Man Who Viewed Too Much in 1995, Mike D’Angelo has also written professionally for Entertainment Weekly, Time Out New York, The Village Voice, Esquire, Las Vegas Weekly, and The A.V. Club, among other publications. He’s been a member of the New York Film Critics Circle and currently blathers opinions almost daily on Patreon.