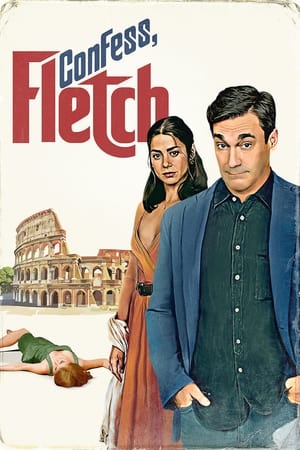

Technically speaking, Confess, Fletch is the third feature adapted from Gregory McDonald’s popular series of novels (published between 1974 and 1986) about Irwin Maurice Fletcher, occasional investigative reporter and near-constant wiseass. As far as any true Fletch fan is concerned, however, we’re starting fresh here, because the two movies starring Chevy Chase in the title role absolutely do not count. Fletch (1985) stuck reasonably close to the first book’s mystery plot but radically refashioned Fletch himself to fit its star’s penchant for broad mugging; the film is lousy (in both senses of the word) with invented bits that allowed Chase to don goofy disguises and trot out silly accents, while every trace of the character’s shrewd intelligence was left behind on the page. It’s as galling a betrayal of a literary cult figure as Hollywood has ever produced, and Fletch Lives (1989), which wasn’t even based on any particular McDonald novel, was even worse—so much worse, in fact, that Fletch died, as a comedic franchise, or at least went into a coma that lasted more than 30 years. And the first question that must be asked about this new film, which sees noted dramatic actor Jon Hamm take over the part, is a very simple one: So, is this Fletch? Is it finally Fletch?

It is, for the most part. One could quibble about casting a 51-year-old as Fletch, who’s described by someone in Confess (the novel) as looking like a typical grad student, and who generally comes across in the early books as if he’s in his late twenties. But Hamm gets the tone right: coolly self-confident, verging on obnoxious, without ever quite crossing the line into smug. This movie, like the book on which it’s based (McDonald’s second Fletch novel, published in 1976), establishes this immediately, when Fletch enters a Boston apartment he’s rented, discovers a murdered woman lying on the floor, and calmly phones the police—not 911, mind you, but just the general precinct line. (Pressed about this, he explains, reasonably enough, that “The emergency part’s kinda…over, you know?”) This kicks off a complicated narrative that’s honestly not worth getting heavily into, because it’s really just a clothesline upon which to string sardonic jibes and eccentric suspects. What matters most is that various pieces of circumstantial evidence point toward Fletch as the killer, obliging him to clear himself by finding the actual culprit while simultaneously attempting to discover who stole, and is now selling, a bunch of valuable paintings that had been owned by the father of his Italian girlfriend, Angela (Lorenza Izzo, actually Chilean), who’s himself been kidnapped. Her father, that is. As I said, there’s a lot going on, but following those requisite twists and turns constitutes a minuscule part of the movie’s pleasures.

Surprisingly, one of Confess, Fletch’s most enjoyable aspects turns out to be Fletch’s lightly antagonistic relationship with the two detectives assigned to the murder case. This is unexpected because it’s an aspect that screenwriters Greg Mottola (who also directed; his most notable previous efforts are The Daytrippers, Superbad and Adventureland) and Zev Borow were forced to invent practically from scratch. Confess, Fletch (the book) introduced another beloved McDonald character, Inspector Francis Xavier Flynn, a garrulous Boston-Irish cop notorious for being averse to arrest suspects until he has them dead to rights. Flynn made such an impression that he wound up getting spun off as the protagonist of a separate mystery series, which I guess is how this movie somehow secured the rights to the novel but not the rights to Flynn, which are currently held by others. Rather than give up or pick a different book, Mottola and Borow simply replaced him with an entirely new character, Inspector Morris Monroe (Daily Show correspondent Roy Wood, Jr.), whose only similarity to Flynn is his convenient willingness to let Fletch roam freely around town despite being the apparent murderer. He has a superior nickname—“Reluctant Flynn” becomes “Slo-Mo Monroe”—and Wood gives him a weary, irritable air that’s attributed to exhaustion from being a new father but also just seems like the proper reaction to Fletch’s brand of relentlessly facile bullshit. Funnier and more endearing still is Monroe’s rookie partner, known only as Griz (Ayden Mayeri); she theoretically replaces a character named Grover, but gets a much wider range of frustrated incredulity than he did, while also very stealthily becoming the movie’s true hero. Give her a spinoff!

Less consistently amusing are the many nutty folks Fletch investigates, virtually all of whom have been expanded or substantially rewritten as well. (Although McDonald’s books seem tailor-made for screen adaptation, being roughly 80% dialogue, it’s actually too much of a good thing—exchanges often go on for pages and pages, chock-full of exposition, whereas cinematic rhythms are much punchier.) Marcia Gay Harden fares best as Angela’s possibly wicked stepmother, the Countess, speaking lines in a barely penetrable purr of a cartoonish Italian accent that rather pointedly turns “Fletch” into “Flesh.” The minor figure of Joan, who lives next door to the apartment Fletch rents, has become Eve (Annie Mumolo, the Barb in Barb and Star Go to Vista Del Mar), an aggressively inane lunatic who provides valuable information while practically setting her own kitchen on fire; I found her a bit much, myself, but was grateful that the broad shtick was coming from supporting players rather than from Fletch, even if he often becomes the straight man in these scenes. Kyle MacLachlan, as a suspicious art dealer, can’t do much with the character’s obsessive germophobia, and poor Lucy Punch, as the wife of the rented apartment’s owner, gets stuck with some truly terrible jokes, e.g. defining “bespoke” as “when an object bespeaks, it betalks, it—no, wait—it beteaches us something about ourselves.” Only John Slattery, playing Fletch’s former newspaper editor (and providing a brief Mad Men reunion), gets to share the McDonald-style naturalistic easiness that’s afforded to Fletch, Monroe and Griz, perhaps because he’s tangential to the story.

That story, as previously mentioned, isn’t terribly satisfying for its own sake (though one could say the same of a stone-cold classic like The Big Sleep). Even in terms of pure comedy, Confess, Fletch is decidedly hit and miss, often more notable for its unusually subdued lighting (Mottola and D.P. Sam Levy aren’t afraid to place the actors in deep shadow when appropriate, even as the tone remains antic) than for its witty repartee. But I’m sorely tempted to tack an extra half-star onto my rating, simply because Hamm makes a solid Fletch and Hollywood has become practically devoid of intelligent iconoclasm. While Mottola has brought the character into the modern world, throwing in podcast jokes and EDM jokes, McDonald conceived him at a time when chafing against authority pretty much dominated entertainment. Temperamentally, Fletch isn’t far removed from the original Hawkeye and Trapper John, as immortalized by Altman’s MASH; this version of Fletch is more akin to Alan Alda’s Hawkeye and Wayne Rogers’ Trapper John—more jovial, less borderline nihilistic—but that’s still a tonic in the present void of DGAF troublemakers. That Paramount is putting zero P&A muscle behind Confess’ release bodes ill for future installments (and I confess that I flinched at the logo for Miramax Films, which I now read as Sexual Assault Films; didn’t realize they were even still in business). Even if one recognizable Fletch is all we ever get, though, that’s still a victory that’s been a long time coming.

One of the first notable online film critics, having launched his site The Man Who Viewed Too Much in 1995, Mike D’Angelo has also written professionally for Entertainment Weekly, Time Out New York, The Village Voice, Esquire, Las Vegas Weekly, and The A.V. Club, among other publications. He’s been a member of the New York Film Critics Circle and currently blathers opinions almost daily on Patreon.