Dive right in

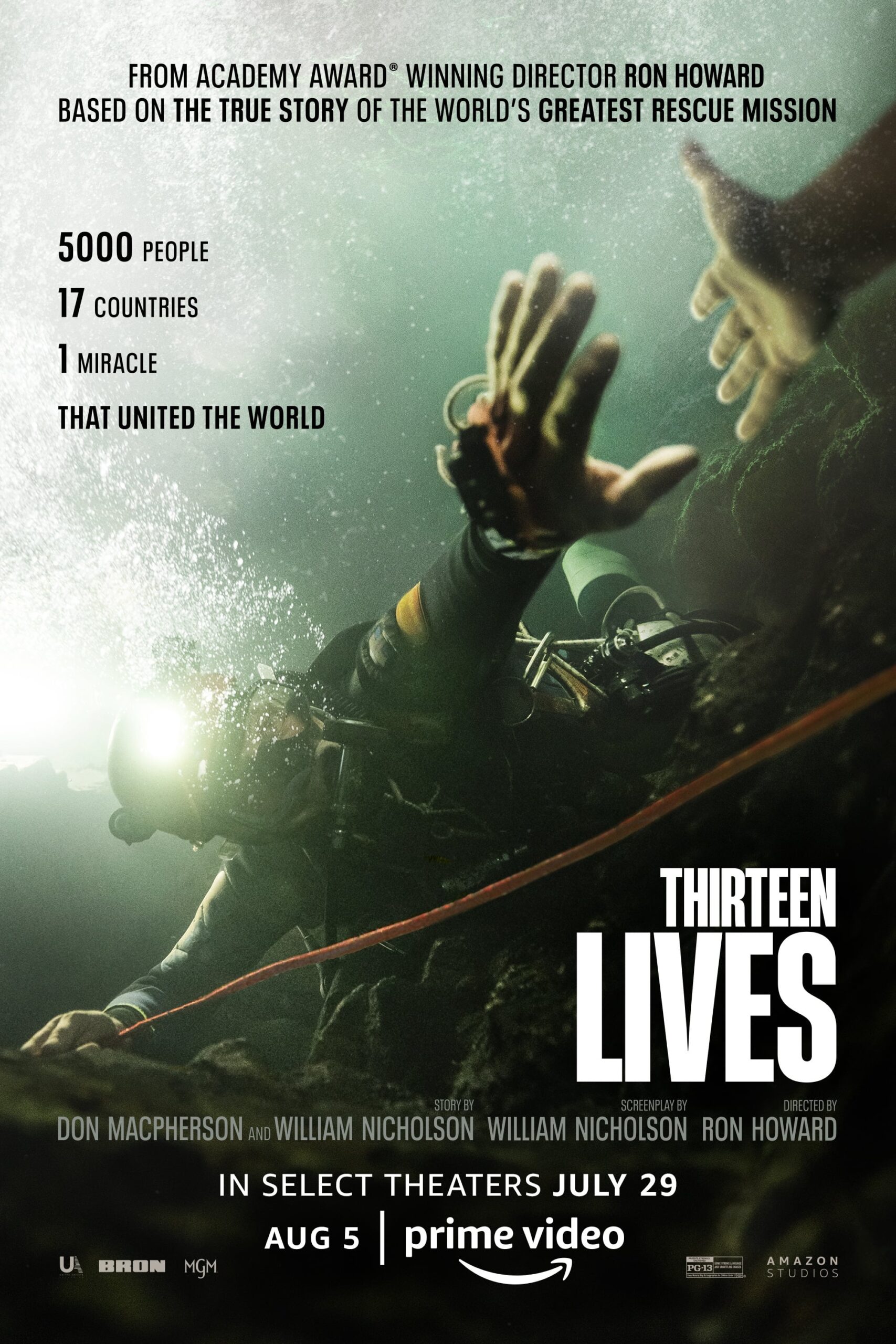

In a long career as Hollywood royalty that has generally swung between the none-too-distant poles of "affably, watchably mediocre" and "tediously mediocre", Ron Howard's best film as a director has long been 1995's Apollo 13, and I would be inclined to say that it's not really a close race. I'm not quite going to say that Thirteen Lives, Howard's latest film, and second in a row to largely debut on streaming after a cursory theatrical release (though unlike the dismal Netflix Original Hillbilly Elegy from 2020, I'd be inclined to say that Thirteen Lives, an Amazon Prime exclusive, would substantially benefit from being seen on a big screen, and more importantly, a big screen in a pitch-dark room), makes a close race. For one thing, I believe I could only go so far as to call it Howard's third-best film also following the 2013 racecar movie Rush. But I would say that the strengths of Thirteen Lives are largely descended from the strengths Apollo 13, a film with a superficially very similar story - a life-or-death situation has erupted in a precarious location and it will take a bunch of extremely well-trained professionals using all of their estimable combined technical knowledge to simply come up with a rescue plan at all, let alone put it into action in a way that might end up working, with the addition of a miracle or two - and a similar focus on executing processes that gives it a rugged stability that Howard's filmography routinely lacks.

Indeed, if not for the existence of Apollo 13, I'd hardly be able to recognise Thirteen Lives as a film with any precursors in Howard's career at all. And even then, it's hardly a direct precursor: Apollo 13 is, after all, a largely heartwarming and solemnly patriotic affair that goes hard on ennobling sentiment. The new film isn't free of ennobling sentiment or warm hearts, particularly near the end, but I think the most immediately noticeable thing about Thirteen Lives is how brusque it is. It's a no-bullshit look at men who are given the absolute minimum amount of backstory sitting around discussing how to define a problem, then how to solve the problem, then solving it; crank the saturation way down and encourage the non-native speakers of English to give much wobblier performances, and I'd certainly have assumed I was looking at a Clint Eastwood film long before I'd have guessed Ron Howard. It's not really making any emotional claims on the audience, a surprising thing for a film about 12 children who are on the brink of drowning in a cave - the film is a dramatisation of the 18-day international humanitarian crisis in 2018 when a dozen tweens and teenagers and their soccer coach were trapped in the Tham Luang Nang Non cave system in northern Thailand during an unexpectedly early monsoon rain on 23 June - but a welcome one. It allows the film to refocus entirely on the tension of the procedure itself, without overloading us on the global melodrama of it all. Instead, it focuses on how, with the implication that how is fascinating enough without going nuts on emotional glad-handling.

It is pretty fascinating - so fascinating that this isn't even the first cinematic treatment of essentially this exact story. The 2021 documentary The Rescue overlaps Thirteen Lives in virtually all particulars: both tell the story largely from the perspective of the British cave divers Richard Stanton and John Volanthen (played in this film by Viggo Mortensen and Colin Farrell, respectively), who were the first to find the trapped kids and were core members of the team that laboriously and perilously brought them to safety; both were legally proscribed from going into very much detail at all about the kids themselves, those life rights having been snapped up by Netflix. The Rescue gets one clear edge over Thirteen Lives, which is that it boasts footage shot during the actual rescue by the actual divers, who were wearing body cameras. Thirteen Lives has the edge of being able to dramatise the planning and strategising and general panicking that The Rescue relegates to pedestrian talking heads interviews.

It also has the edge of Mortensen and Farrell knowing how to be in front of a camera more effectively than the real-life Stanton and Volanthen, no offense to either of those men, and that's even with Mortensen and Farell not really "acting" all that much. In keeping with the film's generally observational, third-person ethos, watching what is happening so astutely that it avoids trying to get too deep into the heads of the people making it happen, neither of the film's lead characters really have "character", and the two extremely gifted performers inhabiting those roles are, in a sense, anti-acting; they're making themselves seems smaller, more anonymous, just part of the mass of humanity involved in trying to rescue the team, rather than particularising the two men (between them, they get one concrete personality trait: Stanton is aggressively pessimistic). These aren't movie star turns - they're barely even character actor turns. But they do end up giving the film a healthy slug of gravitas by having great character actors holding those corners of the plot down.

The relative anonymity of our two closest-thing-we-have-to-leads is all part of how Thirteen Lives operates, which in a fairly hands-off objective mode that's at least somewhat akin to docudrama, though there's enough polished, movie-style construction of individual scenes and shots that you'd never mistake it for nonfiction. But it does have a pretty lean, anti-sensational journalistic vibe, a lot of hand-held cinematography as the camera shoves its way into spaces to watch intently as characters figure out what to do. This is unusual territory for Howard, who tends towards polished, smooth, sentimental filmmaking, but it's also at least somewhat new territory as well for cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom, a genius whose career has included five films directed by Apichatpong Weerasethakul and two by Luca Guadagnino, all of them titanically beautiful. This isn't quite like any of those - it is not, for one thing, beautiful - and yet there's a distinct form of urgent, terribly present physicality that especially resembles his early films with Apichatpong, like Blissfully Yours and Syndromes and a Century. The wet closeness of the underwater cave has been "moviefied" a bit - the water is much easier to see through than in the real-life situation, for one major thing - but it still feels horribly uncomfortable and with a visual sameness that speaks to the confusing, maze-like environment within the cave, especially during the ample quantity of underwater filming in the second half. It's unpleasantly intimate in a way that does a great deal to make everything about the film, underground and above it, in the murky depths of a cave and the overcast jungle outside of it, feel like it's humming with some level of danger and urgency.

It's a very well-built, mercilessly forward-moving thriller, right up in our faces with the decision making of every moment and rarely giving us the out of any kind of sleek filmmaking (Benjamin Wallfisch's learn, terse score, for example, is barely used at all until very late in the film, once it starts to move from the "planning" to the "execution" stage), or easy narrative arcs. We're watching as something exhausting and tough happens. This isn't without its limitations as an approach, the most damning of which is that Thirteen Lives is a remarkably indulgent 147 minutes long, and that's definitely an endurance test, even granting that it's depicting something of an endurance test. I would be lying if I told you that I knew where I'd start cutting, but it still ends up with a movie that feels like it's racing until it isn't, and which is darting from one crisis to another until suddenly it becomes very samey and stretched-out. This doesn't happen without reason, but it's still tough to argue that the film needed quite this much room to tell a story that The Rescue covered much more briskly. But however they add up, the individual scenes are all very exciting and fraught by themselves, and the film manages to do a very good job at suggesting the wide range of people trying to figure out some way to control their corner of all this chaos, with its sprawl part of how it gets at evoking the literal thousands of people involved in the rescue. It's a rock solid, hugely engaging thriller that has very little desire to be anything other than an honest tribute to how something very difficult and very impressive was carried off, and it effortlessly succeeds in that modest but very enjoyable goal.

Indeed, if not for the existence of Apollo 13, I'd hardly be able to recognise Thirteen Lives as a film with any precursors in Howard's career at all. And even then, it's hardly a direct precursor: Apollo 13 is, after all, a largely heartwarming and solemnly patriotic affair that goes hard on ennobling sentiment. The new film isn't free of ennobling sentiment or warm hearts, particularly near the end, but I think the most immediately noticeable thing about Thirteen Lives is how brusque it is. It's a no-bullshit look at men who are given the absolute minimum amount of backstory sitting around discussing how to define a problem, then how to solve the problem, then solving it; crank the saturation way down and encourage the non-native speakers of English to give much wobblier performances, and I'd certainly have assumed I was looking at a Clint Eastwood film long before I'd have guessed Ron Howard. It's not really making any emotional claims on the audience, a surprising thing for a film about 12 children who are on the brink of drowning in a cave - the film is a dramatisation of the 18-day international humanitarian crisis in 2018 when a dozen tweens and teenagers and their soccer coach were trapped in the Tham Luang Nang Non cave system in northern Thailand during an unexpectedly early monsoon rain on 23 June - but a welcome one. It allows the film to refocus entirely on the tension of the procedure itself, without overloading us on the global melodrama of it all. Instead, it focuses on how, with the implication that how is fascinating enough without going nuts on emotional glad-handling.

It is pretty fascinating - so fascinating that this isn't even the first cinematic treatment of essentially this exact story. The 2021 documentary The Rescue overlaps Thirteen Lives in virtually all particulars: both tell the story largely from the perspective of the British cave divers Richard Stanton and John Volanthen (played in this film by Viggo Mortensen and Colin Farrell, respectively), who were the first to find the trapped kids and were core members of the team that laboriously and perilously brought them to safety; both were legally proscribed from going into very much detail at all about the kids themselves, those life rights having been snapped up by Netflix. The Rescue gets one clear edge over Thirteen Lives, which is that it boasts footage shot during the actual rescue by the actual divers, who were wearing body cameras. Thirteen Lives has the edge of being able to dramatise the planning and strategising and general panicking that The Rescue relegates to pedestrian talking heads interviews.

It also has the edge of Mortensen and Farrell knowing how to be in front of a camera more effectively than the real-life Stanton and Volanthen, no offense to either of those men, and that's even with Mortensen and Farell not really "acting" all that much. In keeping with the film's generally observational, third-person ethos, watching what is happening so astutely that it avoids trying to get too deep into the heads of the people making it happen, neither of the film's lead characters really have "character", and the two extremely gifted performers inhabiting those roles are, in a sense, anti-acting; they're making themselves seems smaller, more anonymous, just part of the mass of humanity involved in trying to rescue the team, rather than particularising the two men (between them, they get one concrete personality trait: Stanton is aggressively pessimistic). These aren't movie star turns - they're barely even character actor turns. But they do end up giving the film a healthy slug of gravitas by having great character actors holding those corners of the plot down.

The relative anonymity of our two closest-thing-we-have-to-leads is all part of how Thirteen Lives operates, which in a fairly hands-off objective mode that's at least somewhat akin to docudrama, though there's enough polished, movie-style construction of individual scenes and shots that you'd never mistake it for nonfiction. But it does have a pretty lean, anti-sensational journalistic vibe, a lot of hand-held cinematography as the camera shoves its way into spaces to watch intently as characters figure out what to do. This is unusual territory for Howard, who tends towards polished, smooth, sentimental filmmaking, but it's also at least somewhat new territory as well for cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom, a genius whose career has included five films directed by Apichatpong Weerasethakul and two by Luca Guadagnino, all of them titanically beautiful. This isn't quite like any of those - it is not, for one thing, beautiful - and yet there's a distinct form of urgent, terribly present physicality that especially resembles his early films with Apichatpong, like Blissfully Yours and Syndromes and a Century. The wet closeness of the underwater cave has been "moviefied" a bit - the water is much easier to see through than in the real-life situation, for one major thing - but it still feels horribly uncomfortable and with a visual sameness that speaks to the confusing, maze-like environment within the cave, especially during the ample quantity of underwater filming in the second half. It's unpleasantly intimate in a way that does a great deal to make everything about the film, underground and above it, in the murky depths of a cave and the overcast jungle outside of it, feel like it's humming with some level of danger and urgency.

It's a very well-built, mercilessly forward-moving thriller, right up in our faces with the decision making of every moment and rarely giving us the out of any kind of sleek filmmaking (Benjamin Wallfisch's learn, terse score, for example, is barely used at all until very late in the film, once it starts to move from the "planning" to the "execution" stage), or easy narrative arcs. We're watching as something exhausting and tough happens. This isn't without its limitations as an approach, the most damning of which is that Thirteen Lives is a remarkably indulgent 147 minutes long, and that's definitely an endurance test, even granting that it's depicting something of an endurance test. I would be lying if I told you that I knew where I'd start cutting, but it still ends up with a movie that feels like it's racing until it isn't, and which is darting from one crisis to another until suddenly it becomes very samey and stretched-out. This doesn't happen without reason, but it's still tough to argue that the film needed quite this much room to tell a story that The Rescue covered much more briskly. But however they add up, the individual scenes are all very exciting and fraught by themselves, and the film manages to do a very good job at suggesting the wide range of people trying to figure out some way to control their corner of all this chaos, with its sprawl part of how it gets at evoking the literal thousands of people involved in the rescue. It's a rock solid, hugely engaging thriller that has very little desire to be anything other than an honest tribute to how something very difficult and very impressive was carried off, and it effortlessly succeeds in that modest but very enjoyable goal.

Categories: british cinema, oscarbait, thrillers