When telling a story about truly horrible people, you’ve got two basic choices. Option one: They remain horrible, and either experience a moralistic comeuppance (for several decades, Hollywood’s old Production Code expressly forbade evil to triumph) or, more cynically, thrive as a result. Option two: They eventually achieve some degree of self-awareness, even if that falls well short of an epiphany, and become at least marginally less horrible—a happy ending, usually, but there’s a cynical variant of this one, too, in which repentance and personal growth only make things worse. What’s both interesting and frustrating about The Forgiven, John Michael McDonagh’s fourth feature (and the first one he didn’t write entirely from scratch; it’s adapted from a 2012 novel by Lawrence Osborne), is the way that it pursues both of those options simultaneously, and even heads down each one’s own branching paths. If that approach sounds less than totally coherent, wait ’til you get whiplash from watching it unfold.

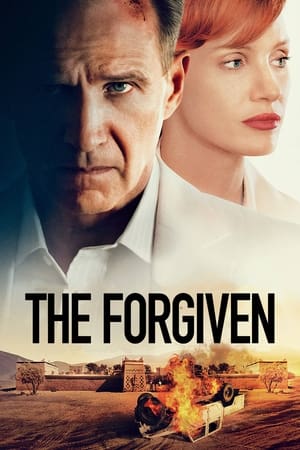

The playing field starts out level, with everyone more or less equally repugnant. That’s true, at least, of all characters whose first language isn’t an Arabic dialect: The Forgiven takes place in the Moroccan desert, where Richard (Matt “the 11th Doctor” Smith) and his boyfriend, Dally (Caleb Landry Jones), live in ostentatious splendor amidst dire poverty, throwing lavish, decadent parties for visiting friends, even as the locals subsist by digging up fossils and selling them to Western tourists. Driving their rental car to one such shindig, Jo and David Henninger (Jessica Chastain and Ralph Fiennes) accidentally hit and kill a young boy, Driss (Omar Ghazaoui), who’d stepped into the road to flag them down, hoping to make a fossil sale. It’s abundantly clear that David’s primarily at fault—he’d been drinking heavily all day, was speeding, and turned his eyes from the road while yelling at Jo—but everyone who’s white perceives the situation as more of a nuisance than a tragedy, thinking only of their own potential liability. Richard smooths things over with the Moroccan police, while David invents a dust storm that obscured his vision. Since Driss was “a nobody,” as David puts it, there’s no reason why his death should affect these wealthy foreigners’ indolent lives.

It's not quite that easy, of course. When Driss’ father (Ismael Kanater) arrives to collect the body, he politely insists that David accompany him to the burial, several hours away—this is local custom, David is told, and it’s strongly implied that refusing would be not just impolite but potentially suicidal. Despite fearing that he’s just as likely to be murdered in revenge if he does go, David ultimately agrees, at which point The Forgiven splits into parallel tracks. While David takes a physical and spiritual journey, gradually coming to recognize his victim’s humanity and his own culpability, Jo remains behind at the party, sublimating her own guilt by flirting heavily with a fellow American guest named Tom (Christopher Abbott). Acting as a sort of Greek chorus throughout is Richard’s head servant, Hamid (Mourad Zaoui), upon whose professionally impassive visage we’re inclined to project our own feelings of disgust; much of Hamid’s dialogue consists of epigrams (“A woman without discretion is like a gold ring in a pig’s snout”) and quoted proverbs (“Open your door to a good day and prepare yourself for a bad one”), prompting a fellow servant, in one of the film’s rare moments of levity, to observe that the guy should really just start a Twitter account.

Jo’s half of The Forgiven is more persuasive, though also less dynamic. Chastain has a tricky job here, as her character doesn’t have a dramatic arc so much as an understandable yet appalling shift in focus; while Jo seems less execrable than her husband from the outset, and it’s hard to blame her for having a fling in his absence (“There you are,” she tells her reflection in the mirror after getting laid, suggesting many years of marital self-abnegation), she’s still using a death that she partially caused and cares little about as means of pursuing her own desires. Complicating matters is how much astringent fun Chastain has being shallow, and the genuine chemistry that she and Abbott share in their scenes together. Had The Forgiven been primarily about Jo getting her groove back via grotesque solipsism—even Richard, who’s built a meaningless life around ignoring his surroundings, at one point reminds of her Driss’ name, after she calls him “that boy” for the umpteenth time—it might have registered more strongly, fully committing to “horrible people learn nothing, remain horrible” but inflecting it with superficial empowerment. That’s an unpleasant viewing experience, to be sure, but productively so if executed with the right amalgam of wit and humanity.

The Forgiven doesn’t commit, however, and its David-centered half feels fundamentally meretricious, even as Fiennes does his best to convey a slow awakening prompted by witnessing (and benefiting from) other people’s acts of kindness and mercy. It’s possible that Osborne’s novel, which I haven’t read, has ample room to explore both Henningers’ psyches, perhaps digging deep into their respective interior monologues. Onscreen, however, the need to keep checking in on Jo back at the party prevents David’s transformation from properly taking hold, undermining key actions he takes during the film’s final moments. It doesn’t help that McDonagh, whose previous films (The Guard, Calvary, War on Everyone), like those of his younger brother Martin, are more notable for their screenplays than for their purely cinematic qualities, opts to illustrate David’s mindset at the very end by having a car radio play the Velvet Underground’s “Venus in Furs,” so that Lou Reed droning “I am tired / I am weary / I could sleep for a thousand years” explains what David will do next. By comparing and contrasting different ways of being a selfish, oblivious asshole—and I haven’t even mentioned the other party guests, who include an aggressively vacuous young woman played by Australian model Abbey Lee and an obnoxious French journalist played by Marie-Josée Croze—The Forgiven manages to come across as ill-defined and overdetermined. That’s a tough combination to pull off, and not an especially rewarding one.

One of the first notable online film critics, having launched his site The Man Who Viewed Too Much in 1995, Mike D’Angelo has also written professionally for Entertainment Weekly, Time Out New York, The Village Voice, Esquire, Las Vegas Weekly, and The A.V. Club, among other publications. He’s been a member of the New York Film Critics Circle and currently blathers opinions almost daily on Patreon.