Blockbuster History: More Germanic mythology

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: at a sufficiently far remove, Thor: Love and Thunder is ultimately based on the legends and mythology of Northern European cultures of the first millennium AD. At much less of a remove, the same broadly defined folklore traditions have previously inspired a much different effects-driven spectacular, from a period when the didn't have "blockbuster-type" movies as such, though this enormous epic would certainly fit the bill if they did.

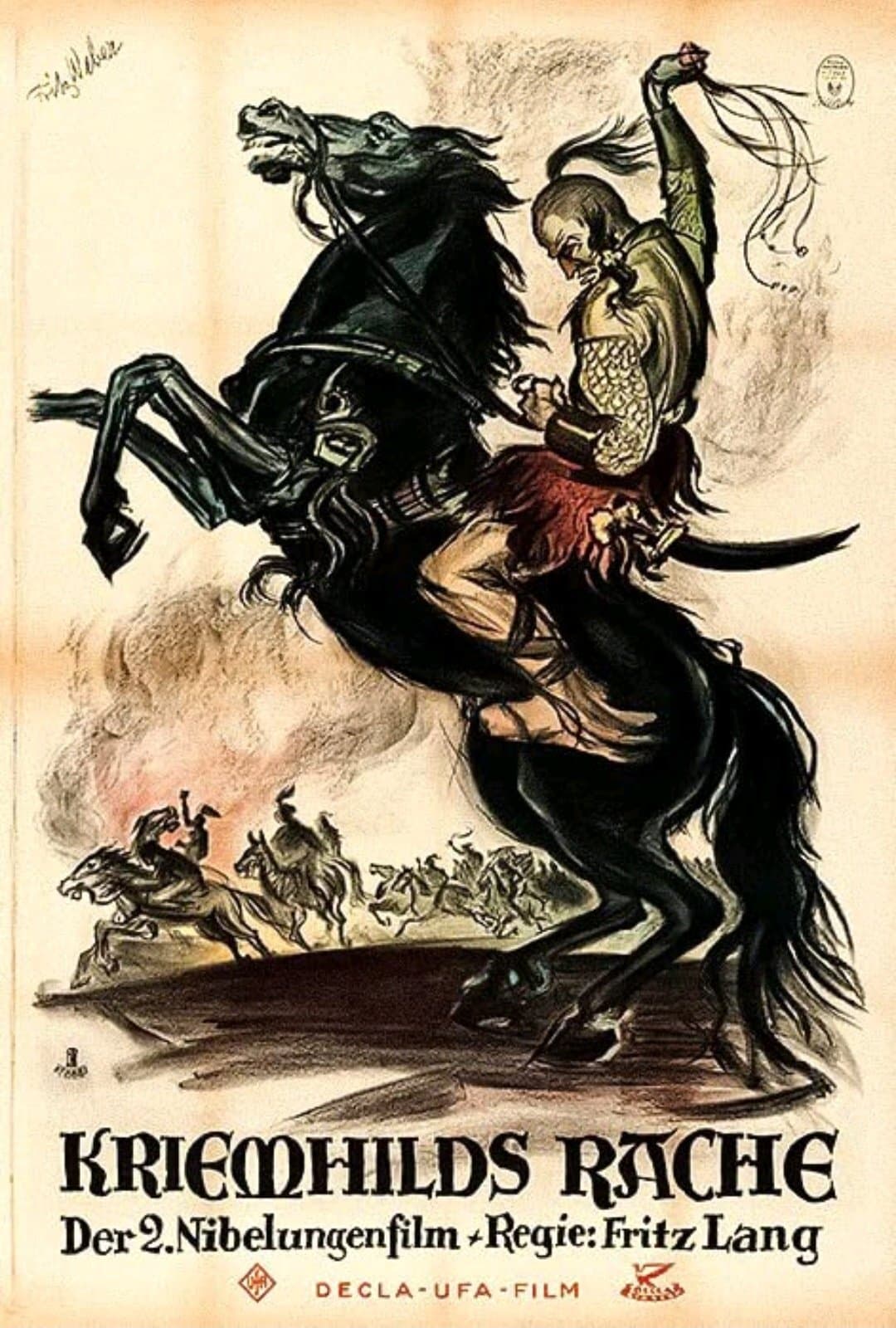

Die Nibelungen: Siegfried and Die Nibelungen: Kriemhild's Revenge are so tightly-bound that it's very possibly a categorical error to suggest that they're two distinct movies: they were written together, produced together, are made by essentially identical casts and crews, they premiered merely ten weeks apart in the winter and spring of 1924, and have mostly been considered as one film of nearly five hours ever since, just "Fritz Lang's Die Nibelungen."

But they certainly don't feel like one movie. Outside of the first "canto" - the name given by director Lang and screenwriter Thea von Harbou to the chapters that make up the whole (a shorter whole, with shorter chapters; the 2012 restoration of Kriemhild's Revenge runs to 131 minutes, compared to Siegfried's 149) - this neither looks nor feels very much like the first half, except in the inherently shared affinities of silent films with a locked-down camera, and the fact that the two parts share the same excitingly idiosyncratic and geometrically-designed wardrobe. The visual strategies are different, the narrative content is different, the genre is different - by the end of the first canto, the villainous Hagen Tronje (Hans Adalbert Schlettow) has stolen the cursed treasure hoard of the Nibelung dwarfs that was brought to the royal court of the Burgundians by the now-dead Siegfried, and dropped it into the Rhine, attempting to wipe clean its curse, and removing any trace of the fantastic and magical from Kriemhild's Revenge. In its place, we get a grim-faced war story and punishing character study about what happens to a woman whose desire for revenge against the men who murdered her husband is so complete that she is willing to fully sacrifice her every last fragment of humanity to pursue it.

That this was evident from very early along in Die Nibelungen's history is attested to by the films' political reception in the 1930s. Put bluntly, the Nazis absolutely loved Siegfried; its story of sturdy Germanic masculinity and awesome mythic potency apparently made it a particularly treasured favorite of Joseph Goebbels himself, and a modestly edited version of that film was kept in circulation well after Lang had fled Germany in 1933. Kriemhild's Revenge, in stark contrast, was mostly hidden away and left unseen (I've read one source claiming it was outright banned, but this seems to be untrue): its pessimistic and angry story of the ugliness of violence and the damage it does to a person's soul, and the devastation wrought upon the Germanic antiheroes as a result of their bloodlust had nothing to do with the bombastic nationalistic myth that the Nazis preferred to make out of Das Nibelungenlied. And so they basically just acted as though the story didn't have a conclusion (which is more or less what they also had to do with Das Nibelungenlied itself).

As if we needed more reason to doubt the Nazis' good judgment. Kriemhild's Revenge is undoubtedly a less rousing, transporting, and simply exciting movie to watch than Siegfried, but it makes up for it by being more emotionally devastating. Death might sweep in to color the end of Siegfried with suffering, but Kriemhild's Revenge is a no-two-ways-about-it tragedy, striding boldly and indefatigably towards its blood-soaked finale from the very first moments we see Kriemhild (Margarete Schön), still pressed into the irresistible fatalistic geometry of the sets defining the Burgundian court, with a granite look of dispassionate hate frozen on her face. I might as well mention now as later, Schön is astonishingly good here; she was one of the better actors in Siegfried, but the competition wasn't steep, and she was certainly not immune to playing the simplest version of a guileless virginal maiden in love, a soppy archetype without very much shading.

Well, the shading arrives with great force in Kriemhild's Revenge. Schön's performance here is, in my opinion, one of the most potent in the whole of silent cinema, assembled of the smallest legible nuances of expression. This is facial acting of the first order, a performance I would sincerely consider placing alongside Maria Falconetti's legendary work in The Passion of Joan of Arc in 1928. Some of the most gut-wrenching moments in the whole of Kriemhild's Revenge consist of nothing whatsoever other than Schön staring forward, her eyes uncannily perfect circles of unblinking, unmoving intensity, bright with the ferocity of her hate - and then she just flexes her eyebrows ever so slightly, and the devastation and loss and anguish that fuel that hate seem to pour out of the film like a biblical flood.

I'm not sure whether Schön's performance drove the style or if the style facilitated Schön's performance, but either way, Lang and his cinematographers favor much closer shot scales than they did in Siegfried. This is a major reason why Kriemhild's Revenge proves to be the more intimate, human-sized half of Die Nibelungen; it is more intimate, giving us much less of the sprawling abstraction of legend in favor of the immediacy of human emotions at their most intense. The moments that most firmly linger in the mind after the movie is over here aren't painterly vistas or fantasy spectacle; they're things like Schön's face wavering as it entirely fills the frame, or her eyes standing out as two bright pinpricks in wide shots of violence, or the solemn, mournful pose, a kind of pagan Pietà, that ends the film over a long, haunting fade to black.

Kriemhild's Revenge belongs to Schön far more than any one character or performance remotely threatens to dominate Siegfried, but there is more to it, almost all of it very good. The story picks up in the immediate wake of Siegfried and Brunhild's deaths at the end of the first part, to find Kriemhild already hunting for a way to get her revenge on her brothers and Hagen, and after her initial plan is spoiled by the disposal of the Nibelung gold (somewhat confusingly, the noun "Nibelung" will come back in this part to mean the Burgundian royal family rather than the dwarf race; a reversion to the source material, but still), but a second option comes immediately when a certain Margrave Rüdiger von Bechlarn (Rudolf Rittner) comes by with an offer that would, in any other circumstance, seem very tasteless: he's an envoy from King Etzel (Rudolf Klein-Rogge) of the Huns, and Etzel has decided to jump at the opportunity of Kriemhild's newfound widowhood to ask for her hand in marriage. She initially refuses, but quickly determines that Etzel's merciless army might be just what she needs to avenge herself, and leaves for the Hunnish lands, where she and Etzel enjoy what seems to be a successful and stable marriage for some years, long enough for her to give birth to his son; but the whole time, Kriemhild is plotting a war, and it eventually erupts in a non-stop sequence of battles that takes up fully the last third of the film's running time.

The difference between the two films is succinctly demonstrated in the gap between how Siegfried protrays the Burgundian court, and how Kriemhild's Revenge portrays the Hunnish camp. The former is excessively stylised in both production design and cinematographer, creating precise, painterly frames. The latter is largely devoid of the airtight geometry of so much of Lang's work, infinitely less "impressive"; it's cluttered and a bit grubby, with extras milling about in shapeless crowds instead of forming faultless lines. One could find in this a comparison between Burgundian civilization and the chaotic violence of the Huns, but that doesn't feel right to me, not least because Etzel, by the time all is said and done, will prove to be the one mostly likable and sympathetic person in the movie, even with Klein-Rogge having been slathered in make-up and costumes made up of a delirious mixture of random signifier of every "The Asiatic Other" that Western culture has ever feared, from the Turks to the Rus to the Mongols (Etzel, incidentally, is none other than Attila, the most famous and infamous Hun leader). Rather, I think the distinction to draw here is between the courtly fantasy of the first film and the unromantic, cruel-minded portrayal of war we get here. Kriemhild's Revenge strips away all of the mythic resonance of Das Nibelungenlied as a nationalistic poem, instead reducing it to the stark truths of its narrative: violence, revenge, and hunger for political power can only destroy. They create nothing beautiful - and so it is that the movie isn't beautiful.

It's still pretty damn impressive, though, especially in those last 45 minutes. I would never think of Lang as an action filmmaker; his strength lies in staging individuals moreso than groups, and in slowness rather than hyperkineticism. And yet, the battle scenes at the end of Kriemhild's Revenge are extraordinary, powerful and enthralling even in their bleakness and wantonness. Masses of extras swarm through sets, creating a frenzy of brutal medieval combat that's never lovely or elegant, always heavy and rough - but it's vivid, visceral cinema, just as much as Schön's powerful expressions are. And this is what this film does for Die Nibelungen as a whole: it creates the dark spectacle to counterbalance Siegfried's lighter spectacle, just as its resolutely human story counterbalances that film's more detached, mythic story. Combined into one massive body, they are a remarkably complete and all-encompassing example of just how much cinema is capable of: an exciting and crushing, ennobling and dispiriting, beautifully ugly spectacle that comes as close as the movies have to truly earning the word "epic".

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

Die Nibelungen: Siegfried and Die Nibelungen: Kriemhild's Revenge are so tightly-bound that it's very possibly a categorical error to suggest that they're two distinct movies: they were written together, produced together, are made by essentially identical casts and crews, they premiered merely ten weeks apart in the winter and spring of 1924, and have mostly been considered as one film of nearly five hours ever since, just "Fritz Lang's Die Nibelungen."

But they certainly don't feel like one movie. Outside of the first "canto" - the name given by director Lang and screenwriter Thea von Harbou to the chapters that make up the whole (a shorter whole, with shorter chapters; the 2012 restoration of Kriemhild's Revenge runs to 131 minutes, compared to Siegfried's 149) - this neither looks nor feels very much like the first half, except in the inherently shared affinities of silent films with a locked-down camera, and the fact that the two parts share the same excitingly idiosyncratic and geometrically-designed wardrobe. The visual strategies are different, the narrative content is different, the genre is different - by the end of the first canto, the villainous Hagen Tronje (Hans Adalbert Schlettow) has stolen the cursed treasure hoard of the Nibelung dwarfs that was brought to the royal court of the Burgundians by the now-dead Siegfried, and dropped it into the Rhine, attempting to wipe clean its curse, and removing any trace of the fantastic and magical from Kriemhild's Revenge. In its place, we get a grim-faced war story and punishing character study about what happens to a woman whose desire for revenge against the men who murdered her husband is so complete that she is willing to fully sacrifice her every last fragment of humanity to pursue it.

That this was evident from very early along in Die Nibelungen's history is attested to by the films' political reception in the 1930s. Put bluntly, the Nazis absolutely loved Siegfried; its story of sturdy Germanic masculinity and awesome mythic potency apparently made it a particularly treasured favorite of Joseph Goebbels himself, and a modestly edited version of that film was kept in circulation well after Lang had fled Germany in 1933. Kriemhild's Revenge, in stark contrast, was mostly hidden away and left unseen (I've read one source claiming it was outright banned, but this seems to be untrue): its pessimistic and angry story of the ugliness of violence and the damage it does to a person's soul, and the devastation wrought upon the Germanic antiheroes as a result of their bloodlust had nothing to do with the bombastic nationalistic myth that the Nazis preferred to make out of Das Nibelungenlied. And so they basically just acted as though the story didn't have a conclusion (which is more or less what they also had to do with Das Nibelungenlied itself).

As if we needed more reason to doubt the Nazis' good judgment. Kriemhild's Revenge is undoubtedly a less rousing, transporting, and simply exciting movie to watch than Siegfried, but it makes up for it by being more emotionally devastating. Death might sweep in to color the end of Siegfried with suffering, but Kriemhild's Revenge is a no-two-ways-about-it tragedy, striding boldly and indefatigably towards its blood-soaked finale from the very first moments we see Kriemhild (Margarete Schön), still pressed into the irresistible fatalistic geometry of the sets defining the Burgundian court, with a granite look of dispassionate hate frozen on her face. I might as well mention now as later, Schön is astonishingly good here; she was one of the better actors in Siegfried, but the competition wasn't steep, and she was certainly not immune to playing the simplest version of a guileless virginal maiden in love, a soppy archetype without very much shading.

Well, the shading arrives with great force in Kriemhild's Revenge. Schön's performance here is, in my opinion, one of the most potent in the whole of silent cinema, assembled of the smallest legible nuances of expression. This is facial acting of the first order, a performance I would sincerely consider placing alongside Maria Falconetti's legendary work in The Passion of Joan of Arc in 1928. Some of the most gut-wrenching moments in the whole of Kriemhild's Revenge consist of nothing whatsoever other than Schön staring forward, her eyes uncannily perfect circles of unblinking, unmoving intensity, bright with the ferocity of her hate - and then she just flexes her eyebrows ever so slightly, and the devastation and loss and anguish that fuel that hate seem to pour out of the film like a biblical flood.

I'm not sure whether Schön's performance drove the style or if the style facilitated Schön's performance, but either way, Lang and his cinematographers favor much closer shot scales than they did in Siegfried. This is a major reason why Kriemhild's Revenge proves to be the more intimate, human-sized half of Die Nibelungen; it is more intimate, giving us much less of the sprawling abstraction of legend in favor of the immediacy of human emotions at their most intense. The moments that most firmly linger in the mind after the movie is over here aren't painterly vistas or fantasy spectacle; they're things like Schön's face wavering as it entirely fills the frame, or her eyes standing out as two bright pinpricks in wide shots of violence, or the solemn, mournful pose, a kind of pagan Pietà, that ends the film over a long, haunting fade to black.

Kriemhild's Revenge belongs to Schön far more than any one character or performance remotely threatens to dominate Siegfried, but there is more to it, almost all of it very good. The story picks up in the immediate wake of Siegfried and Brunhild's deaths at the end of the first part, to find Kriemhild already hunting for a way to get her revenge on her brothers and Hagen, and after her initial plan is spoiled by the disposal of the Nibelung gold (somewhat confusingly, the noun "Nibelung" will come back in this part to mean the Burgundian royal family rather than the dwarf race; a reversion to the source material, but still), but a second option comes immediately when a certain Margrave Rüdiger von Bechlarn (Rudolf Rittner) comes by with an offer that would, in any other circumstance, seem very tasteless: he's an envoy from King Etzel (Rudolf Klein-Rogge) of the Huns, and Etzel has decided to jump at the opportunity of Kriemhild's newfound widowhood to ask for her hand in marriage. She initially refuses, but quickly determines that Etzel's merciless army might be just what she needs to avenge herself, and leaves for the Hunnish lands, where she and Etzel enjoy what seems to be a successful and stable marriage for some years, long enough for her to give birth to his son; but the whole time, Kriemhild is plotting a war, and it eventually erupts in a non-stop sequence of battles that takes up fully the last third of the film's running time.

The difference between the two films is succinctly demonstrated in the gap between how Siegfried protrays the Burgundian court, and how Kriemhild's Revenge portrays the Hunnish camp. The former is excessively stylised in both production design and cinematographer, creating precise, painterly frames. The latter is largely devoid of the airtight geometry of so much of Lang's work, infinitely less "impressive"; it's cluttered and a bit grubby, with extras milling about in shapeless crowds instead of forming faultless lines. One could find in this a comparison between Burgundian civilization and the chaotic violence of the Huns, but that doesn't feel right to me, not least because Etzel, by the time all is said and done, will prove to be the one mostly likable and sympathetic person in the movie, even with Klein-Rogge having been slathered in make-up and costumes made up of a delirious mixture of random signifier of every "The Asiatic Other" that Western culture has ever feared, from the Turks to the Rus to the Mongols (Etzel, incidentally, is none other than Attila, the most famous and infamous Hun leader). Rather, I think the distinction to draw here is between the courtly fantasy of the first film and the unromantic, cruel-minded portrayal of war we get here. Kriemhild's Revenge strips away all of the mythic resonance of Das Nibelungenlied as a nationalistic poem, instead reducing it to the stark truths of its narrative: violence, revenge, and hunger for political power can only destroy. They create nothing beautiful - and so it is that the movie isn't beautiful.

It's still pretty damn impressive, though, especially in those last 45 minutes. I would never think of Lang as an action filmmaker; his strength lies in staging individuals moreso than groups, and in slowness rather than hyperkineticism. And yet, the battle scenes at the end of Kriemhild's Revenge are extraordinary, powerful and enthralling even in their bleakness and wantonness. Masses of extras swarm through sets, creating a frenzy of brutal medieval combat that's never lovely or elegant, always heavy and rough - but it's vivid, visceral cinema, just as much as Schön's powerful expressions are. And this is what this film does for Die Nibelungen as a whole: it creates the dark spectacle to counterbalance Siegfried's lighter spectacle, just as its resolutely human story counterbalances that film's more detached, mythic story. Combined into one massive body, they are a remarkably complete and all-encompassing example of just how much cinema is capable of: an exciting and crushing, ennobling and dispiriting, beautifully ugly spectacle that comes as close as the movies have to truly earning the word "epic".

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!