Sometimes we Americans get cheated out of a perfect title. Claire Denis’ 14th or 15th solo narrative feature—depends upon whether you want to count 1994’s magnificent, hour-long U.S. Go Home, made for the same remarkable French anthology TV series that gave us Olivier Assayas’ Cold Water and André Téchiné’s Wild Reeds; “Denis’ latest film” would be inaccurate, as she’s already made another that premiered at Cannes six weeks ago—anyway, this particular Denis joint is being released in the U.S. as Both Sides of the Blade, which is also the title of a typically melancholy Tindersticks song that plays over its closing credits. Whether the song inspired the title or was written expressly for the film, I don’t know; either way, those five words are evocative enough, and a significant improvement upon Fire, the film’s banal alternate English-language title (and still the one favored by IMDb as I write this). In the original French, however, this portrait of a volatile love triangle is called Avec amour et encharnement, which translates roughly as With Love and Ferocity. I’d go see that movie, and I wouldn’t feel cheated: Denis, in her second collaboration with author Christine Angot (following 2017’s Let the Sunshine In) and her third consecutive feature starring Juliette Binoche (add 2018’s High Life), foregrounds those two emotions almost to the exclusion of everything else.

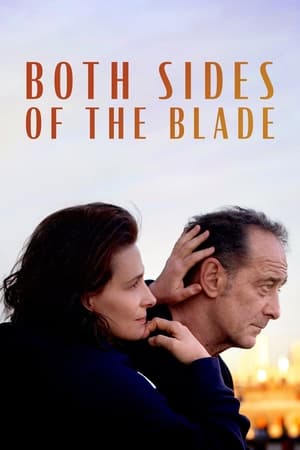

Indeed, we have here a blade so thin that I’m not convinced it actually has two sides. The film’s basic premise could hardly be more simple or more universal: marriage, affair, anger, tears. Denis opens with the standard idyll, showing Sara (Binoche) and Jean (Vincent Lindon) canoodling in the ocean during a summer vacation, clearly very much in love. They’ve been together for about nine years, but it’s still the kind of relationship that sees Sara wrap her arms affectionately around Jean’s waist from behind as he stretches his own arms up to adjust a window awning, or just gaze lovingly at him from the other room. Their sex life seems altogether healthy, in a long-term, middle-aged, credibly unspectacular sort of way. It’s only after Sara spots another man (Grégoire Colin) on the street that storm clouds gather. This fellow turns out to be François, an ex-boyfriend of Sara’s who was also once Jean’s business partner; apparently—and I’ll return to that adverb in a moment—he’s been elsewhere for the past decade or so, and has only just returned to Paris. Whether he was semi-stalking Sara (who sees him across the street from the studio where she works as either a radio personality or podcast host, interviewing guests about current events) isn’t clear, but it’s Jean he soon contacts, proposing that they again join forces as rugby talent scouts. Sara encourages the idea even as she reassures Jean that she’s long since over François and he has no need to worry. Jean wasn’t worried, as it happens, but now he is.

And with good reason. Both Sides of the Blade is a frustrating film in many respects, but it powerfully conveys the tractor-beam pull that a lover from the past can exert; that’s an entirely different experience from falling for somebody new (a subject that Denis tackled 20 years ago in Friday Night, which likewise starred Lindon), less frequently depicted onscreen. While Binoche gives a nuanced, naturalistic performance in most scenes, she goes big and bold in relation to François (assisted by Tindersticks’ score, abruptly cranked to an operatic level), with Sara sometimes appearing as if she might actually faint from the sheer intensity of her feelings. His effect upon her is immediate and physical and ungovernable, though she does manage at one point to pull back when he tries to kiss her on the mouth within view of Jean. (This then becomes fodder for a huge argument, as Sara accurately and self-righteously insists to Jean that she ducked the kiss in question even as she lies to him about everything of importance.) Does François share Sara’s undying ardor? He claims to do so, but Colin keeps him somewhat closed off, making it difficult to assess whether he’s sincere or just indulging in nostalgia, possibly with an element of revenge mixed in as well.

“Possibly,” I just said, having promised to circle back to an earlier “apparently.” Having spent the past quarter-century complaining about films that drown viewers in needless exposition and backstory, I’m constitutionally averse to demanding more information than we’ve been given, so this next part’s gonna entail some psychic agony for me. But there’s no getting around it: Both Sides of the Blade withholds so much genuinely crucial history involving its three main characters that parsing their situation becomes nearly impossible. The most notable instance involves an unspecified stretch of time that Jean spent in prison: We never learn why he was arrested; it’s not at all clear how long he was inside, or what Sara was doing during that period; there are vague suggestions that François wasn’t wholly removed from whatever went down, but they’re so vague as to leave the viewer adrift regarding whether either man—or Sara, for that matter—has cause to feel lingering resentment about what happened. Which kinda matters, given the circumstances! Nor do we know why Sara and François broke up in the first place. Frankly, the film would make far more sense had François just been released from prison after many years. As is, there’s no evident reason why he and Sara didn’t just get back together while Jean was behind bars; I can imagine a few, to be sure, but all we actually get is stray dialogue to the effect that François had gone away somewhere. Did Sara err in settling for a cozy but passion-free life with Jean, leaving a soulmate-sized hole in her heart? Or is she now infatuated with an opportunistic asshole? Ambiguity’s wonderful, but that’s not what’s at work here—instead, it just feels as if nobody ever made any decision at all.

Denis and Angot adapted Both Sides from the latter’s novel Un tournant de la vie (another title! that one refers to a turning point in one’s life), and it’s entirely possible that they chose to omit details that Angot had fleshed out on the page. On the other hand, they found time to either include or invent (more likely the former) a significant subplot about Jean’s 15-year-old mixed-race son from a prior marriage, Marcus (Issa Perica), having Jean repeatedly check in with the boy (who lives with Jean’s mother, played by the great Bulle Ogier) and lecture him about doing his schoolwork and not allowing himself to be defined by other people’s unhelpful “discourse” about minorities. At no point does this paternal relationship dovetail with the romantic one, except perhaps in the superficial sense that Marcus’ existence constitutes the residue of a past relationship. Mostly, it just raises more unanswered questions about Jean’s time in prison—whether he entrusted Marcus to Grandma long ago when he was arrested (the boy’s mother went back to Martinique, we’re informed) and then decided to leave him there upon release. Again, the film isn’t interested in this stuff at all, and assumes that we won’t care, either. But then why bother including any of it? Both Sides of the Blade runs just shy of two hours, yet leaves key matters unexplored while taking trivial tangents. It’s just perverse.

Maybe that would seem less irksome were the movie as a whole more perverse, à la High Life or Bastards. But Denis and Angot have stripped their scenario down to its essence, and that essence proves to be entirely conventional—just a standard-issue infidelity melodrama with the motivational scaffolding removed. Everything builds to a climactic shouting match that’s at once rhetorically familiar (not least in the man constantly insisting that he’s perfectly calm when he’s obviously highly agitated) and visually undistinguished (with D.P. Eric Gautier shooting close and handheld in a way that gives Binoche and Lindon as much free rein as possible, at the expense of any compositional precision; I submit that this style’s extremely hard to execute well with a single camera, as one ends up constantly whip-panning from face to face). Both Sides of the Blade is strongest when focused most intently upon Sara; its headiest moment finds her staring at her reflection, nude, in the middle of the night, muttering “Here we go again: love, fear, sleepless nights, the phone at my bedside, getting wet.” That’s an arresting dynamic, and it merited richer, more specific treatment than it gets here, as well as a stronger resolution than someone literally, unironically flipping a table.

One of the first notable online film critics, having launched his site The Man Who Viewed Too Much in 1995, Mike D’Angelo has also written professionally for Entertainment Weekly, Time Out New York, The Village Voice, Esquire, Las Vegas Weekly, and The A.V. Club, among other publications. He’s been a member of the New York Film Critics Circle and currently blathers opinions almost daily on Patreon.