Blockbuster History: Dinosaurs walk among us

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: Jurassic World Dominion continues its franchise's burning question of what happens in a version of the modern world where human/dinosaur interactions have been normalised. This subject has excited filmmakers' speculation since the days of ripping off the very first Jurassic Park.

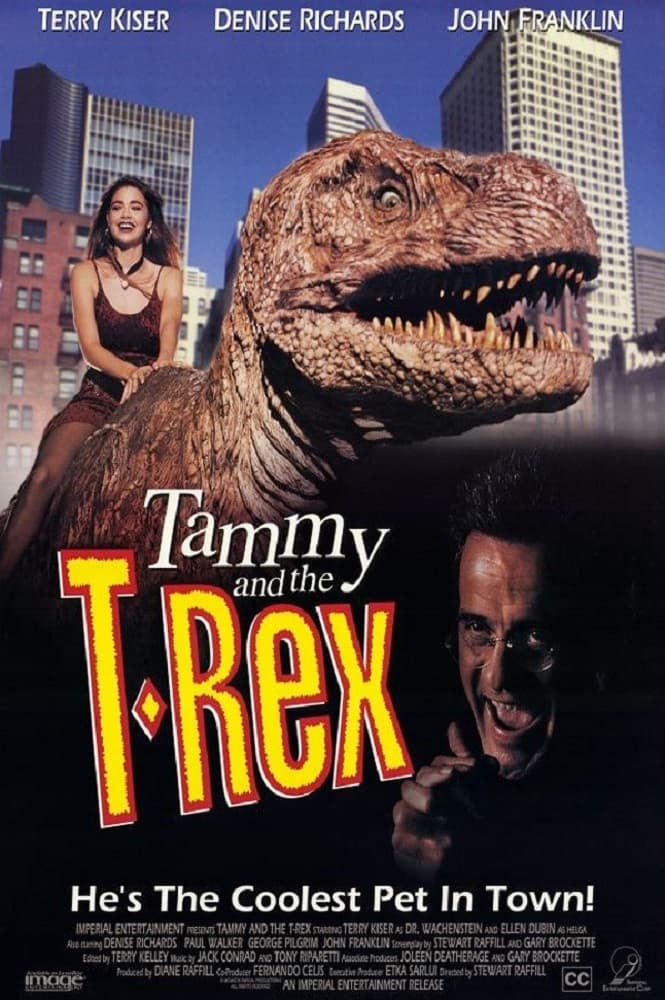

We must extend all credit, and extend it with warmth and sincerity, to the good old-fashioned Poverty Row genius of the filmmakers behind 1994's Tammy and the T-Rex. This is one of those "we can make the movie if we make it RIGHT NOW" jobs born less out of artistic inspiration than the immediate short-term access to resources that might, if you play your cards right, get you a couple of weeks' play in a market hungry for what those resources represent. Done right, this is the kind of fast-moving professionalism that leads Roger Corman to make The Little Shop of Horrors in a long weekend, because he still had the sets and crew. Done poorly, and, well, it's Tammy and the T-Rex, but I really meant it when I said I was sincere. The husband-and-wife team of director Stewart Raffill and producer Diane Kirman (credited for the only time in her career as "Diane Raffill") might not have made a lot out of the movie, but they did make a movie out of it, on less than two week's notice. And there's an undeniably wobbly, ramshackle charm to what they were able to crap out in a hurry

The splendid resource in question was the T-Rex itself, an animatronic that had been told to an amusement park in Texas, but wasn't going to change hands till the end of the month. And so its owner, in his last weeks of possessing the dumb thing, proposed to the Raffills that they should put it in a movie. So Stewart wrote a screenplay out of nothing, not even a bare idea for a story, in one week, along with actor and first-time writer Gary Brockette (who'd acted in a few of the director's films, including the notorious Mac and Me, and been the script supervisor on a couple others, including the infamous Mannequin Two: On the Move). He designed the story so that every location could be reached from his house within a half of an hour. It's genuinely kind of brilliant.

More astonishing still, it's genuinely kind of ambitious. If I had been given this exact same problem, I would have taken the coward's route: written things so that we could knock out all of the T-Rex scenes in a maybe a day or two of shooting with a bunch of isolated shots that could then be dribbled across the movie to make it seem like there's more of them, the way you do with a famous actor when you can only afford them for a single day of shooting. And then, with the pressure of time off, I'd have shot the non-T-Rex scenes at a more manageable pace. None of this for Tammy and the T-Rex! The T-Rex animatronic gets a ton of screentime, in several noticeably different locations, interacting with virtually all of the important human actors in the cast. Raffill made things hard on himself, and he still got the job done, and there's just no way around it: that's admirable, damned admirable.

Note that I have thus far praised Tammy and the T-Rex exclusively in terms of its low-budget producing know-how, and not because I think it's fun to watch the finished product. Which isn't entirely fair - there are more than a few moments of pure so-bad-it's-good bliss, and it is to the movie's great benefit that one of the very best of these comes right at the very end, so you're left on a high note. And let us be clear, so-bad-it's-good was probably the only way this was ever going to come out of that dementedly fast production schedule as an enjoyable, watchable object. Roger Corman could work on that kind of model and manage to squeeze out something that's unironically fun and even smart in some tiny ways, but it's not surprising that the director of Mac and Me couldn't. There were inevitable problems baked into the cake here: a story that feels like it's just tossing ideas out to see which land, under-rehearsed actors, continuity errors, takes that needed a do-over that there wasn't time for.

It's just as inevitable that the film cobbled together out of those problems would be, in long chunks, a pretty crummy slog. The story the film landed on centers on Michael (Paul Walker), a high school football player, who has just started dating the titular Tammy (Denise Richards, whose casting was clearly meant to make the character even more titular), over the terrifyingly violent objections of her psychopathic ex, Billy (George Pilgrim). Billy is not a reasonable sort, and so he and his gang deal with his feelings of rejection by throwing Michael into the lion enclosure at the zoo, where he is mauled to within an inch of his life. This is perfect timing - not for Tammy or Michael, but for Dr. Gunter Wachenstein (Terry Kiser), who has a brand new robotic Tyrannosaurus rex that he's got no apparent use for. He's been hoping to implant a human brain in the robot, and a freshly-dead teenage boy seems like a good candidate. So Wachenstein and his assistant Helga (Ellen Dubin) sneak into the hospital, pretend to be doctors on staff, and take Michael off of life support, later grave-robbing his still-viable brain out of his corpse. And before you know it, he's meandering around suburban Los Angeles, trying to communicate with Tammy that he's still the man he loved, even though he is not, sensu stricto, a man any more. For her part, she figures this out pretty quickly, and conscripts her black gay best friend Byron (Theo Forsett) to help hunt for a body. Also, Michael figures that since he's a god-damned dinosaur these days, he might as well eat Billy and his gang.

Setting aside the wandering mess of a story, what really stands out here is that Tammy and the T-Rex is a real mixed bag of random tones. The film was shot, and initially cut, to be a violent R-rated slapstick rampage, but was hastily butchered down by eight minutes when the distributor wanted something closer to an all-ages Jurassic Park rip-off. And you can easily see why they thought that would work: the unabashed, unavoidable chintziness of the production screams "direct to video kid-vid schlock". It's a powerfully broad, shticky comedy, and that broadness frequently registers as dumb, goofy kids' stuff. At the same time, it has a certain leering, sleazy quality, casting Richards primarily so she could run around jiggling, and it ends with her performing a striptease, while her boyfriend's brain-in-a-jar rattles around shooting off sparks and orgasming. There is a long scene at the beginning - hours long - I'm still waiting for it to end, really - where Michael and Billy get into a fight that involves both of them firmly gripping the other by the testicles (the button on the "joke", if we can dignify it with such a word, is that Michael is wearing a cup), refusing to unclench until the cops come and force them apart. And yes, violence-against-balls humor is a time-honored all-ages tradition, but in this case there's something sort of indefinably but unmistakably seedy and crass about it. Byron is a stunningly off-putting mixture of the tackiest, most offensive clichés about African-Americans and gay men that 1994-era filmmakers could have ever convinced themselves was "progressive".

And then there's the gore, which was always present in foreign releases of the film, but was lovingly restored by the people at Vinegar Syndrome in 2019. Thank God they did, because the gore is a rare highlight, and almost all of the actually funny-on-purpose jokes are the ones where some disgusting bit of slapstick has just occurred. But put back into its place of privilege, the gore just amplifies the question of what the hell this film is doing. Is it kiddie schlock? Obnoxious douchey comedy for meanspirited high school bros? A gift to the gorehounds disappointed that Jurassic Park pulled its punches? Somehow, it's "yes" to all three, and the film is just as confounding as that triangulation implies.

In amidst all of its tonal problems, the fact that Tammy and the T-Rex is just plain bad filmmaking sort of doesn't register; there's a zesty enthusiasm to much of its badness that makes it feel more like a '50s or '60s B-movie than the kind of angrily mediocre crap getting spewed out direct-to-video in the '90s. There are some elements that are simply too tedious to pretend they're anything fun - in particular, Richard's performance is bad even compared to her reliably poor work in actual big-budget projects later in the decade and she's called upon to bear the entire emotional arc - but the more that it's just a dopey creature feature, the more playful it is. Michael the T-theRex is frequently fitted out with little rubber arms coming in from a side of the screen where they obviously don't match his body, while he does things like try to call Tammy on a pay phone (this is quite obviously the film's best scene); Kriser's performance as a generic mad scientist is the right kind of "antagonist on a Saturday morning kids' show" clowning around. I would not, on balance, say that Tammy and the T-Rex has enough of this kind of thing going on that it's ultimately a terribly watchable bad movie, but it has its moments, enough of them to look pretty good by the utterly dispiriting standards of '90s bad movies.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

We must extend all credit, and extend it with warmth and sincerity, to the good old-fashioned Poverty Row genius of the filmmakers behind 1994's Tammy and the T-Rex. This is one of those "we can make the movie if we make it RIGHT NOW" jobs born less out of artistic inspiration than the immediate short-term access to resources that might, if you play your cards right, get you a couple of weeks' play in a market hungry for what those resources represent. Done right, this is the kind of fast-moving professionalism that leads Roger Corman to make The Little Shop of Horrors in a long weekend, because he still had the sets and crew. Done poorly, and, well, it's Tammy and the T-Rex, but I really meant it when I said I was sincere. The husband-and-wife team of director Stewart Raffill and producer Diane Kirman (credited for the only time in her career as "Diane Raffill") might not have made a lot out of the movie, but they did make a movie out of it, on less than two week's notice. And there's an undeniably wobbly, ramshackle charm to what they were able to crap out in a hurry

The splendid resource in question was the T-Rex itself, an animatronic that had been told to an amusement park in Texas, but wasn't going to change hands till the end of the month. And so its owner, in his last weeks of possessing the dumb thing, proposed to the Raffills that they should put it in a movie. So Stewart wrote a screenplay out of nothing, not even a bare idea for a story, in one week, along with actor and first-time writer Gary Brockette (who'd acted in a few of the director's films, including the notorious Mac and Me, and been the script supervisor on a couple others, including the infamous Mannequin Two: On the Move). He designed the story so that every location could be reached from his house within a half of an hour. It's genuinely kind of brilliant.

More astonishing still, it's genuinely kind of ambitious. If I had been given this exact same problem, I would have taken the coward's route: written things so that we could knock out all of the T-Rex scenes in a maybe a day or two of shooting with a bunch of isolated shots that could then be dribbled across the movie to make it seem like there's more of them, the way you do with a famous actor when you can only afford them for a single day of shooting. And then, with the pressure of time off, I'd have shot the non-T-Rex scenes at a more manageable pace. None of this for Tammy and the T-Rex! The T-Rex animatronic gets a ton of screentime, in several noticeably different locations, interacting with virtually all of the important human actors in the cast. Raffill made things hard on himself, and he still got the job done, and there's just no way around it: that's admirable, damned admirable.

Note that I have thus far praised Tammy and the T-Rex exclusively in terms of its low-budget producing know-how, and not because I think it's fun to watch the finished product. Which isn't entirely fair - there are more than a few moments of pure so-bad-it's-good bliss, and it is to the movie's great benefit that one of the very best of these comes right at the very end, so you're left on a high note. And let us be clear, so-bad-it's-good was probably the only way this was ever going to come out of that dementedly fast production schedule as an enjoyable, watchable object. Roger Corman could work on that kind of model and manage to squeeze out something that's unironically fun and even smart in some tiny ways, but it's not surprising that the director of Mac and Me couldn't. There were inevitable problems baked into the cake here: a story that feels like it's just tossing ideas out to see which land, under-rehearsed actors, continuity errors, takes that needed a do-over that there wasn't time for.

It's just as inevitable that the film cobbled together out of those problems would be, in long chunks, a pretty crummy slog. The story the film landed on centers on Michael (Paul Walker), a high school football player, who has just started dating the titular Tammy (Denise Richards, whose casting was clearly meant to make the character even more titular), over the terrifyingly violent objections of her psychopathic ex, Billy (George Pilgrim). Billy is not a reasonable sort, and so he and his gang deal with his feelings of rejection by throwing Michael into the lion enclosure at the zoo, where he is mauled to within an inch of his life. This is perfect timing - not for Tammy or Michael, but for Dr. Gunter Wachenstein (Terry Kiser), who has a brand new robotic Tyrannosaurus rex that he's got no apparent use for. He's been hoping to implant a human brain in the robot, and a freshly-dead teenage boy seems like a good candidate. So Wachenstein and his assistant Helga (Ellen Dubin) sneak into the hospital, pretend to be doctors on staff, and take Michael off of life support, later grave-robbing his still-viable brain out of his corpse. And before you know it, he's meandering around suburban Los Angeles, trying to communicate with Tammy that he's still the man he loved, even though he is not, sensu stricto, a man any more. For her part, she figures this out pretty quickly, and conscripts her black gay best friend Byron (Theo Forsett) to help hunt for a body. Also, Michael figures that since he's a god-damned dinosaur these days, he might as well eat Billy and his gang.

Setting aside the wandering mess of a story, what really stands out here is that Tammy and the T-Rex is a real mixed bag of random tones. The film was shot, and initially cut, to be a violent R-rated slapstick rampage, but was hastily butchered down by eight minutes when the distributor wanted something closer to an all-ages Jurassic Park rip-off. And you can easily see why they thought that would work: the unabashed, unavoidable chintziness of the production screams "direct to video kid-vid schlock". It's a powerfully broad, shticky comedy, and that broadness frequently registers as dumb, goofy kids' stuff. At the same time, it has a certain leering, sleazy quality, casting Richards primarily so she could run around jiggling, and it ends with her performing a striptease, while her boyfriend's brain-in-a-jar rattles around shooting off sparks and orgasming. There is a long scene at the beginning - hours long - I'm still waiting for it to end, really - where Michael and Billy get into a fight that involves both of them firmly gripping the other by the testicles (the button on the "joke", if we can dignify it with such a word, is that Michael is wearing a cup), refusing to unclench until the cops come and force them apart. And yes, violence-against-balls humor is a time-honored all-ages tradition, but in this case there's something sort of indefinably but unmistakably seedy and crass about it. Byron is a stunningly off-putting mixture of the tackiest, most offensive clichés about African-Americans and gay men that 1994-era filmmakers could have ever convinced themselves was "progressive".

And then there's the gore, which was always present in foreign releases of the film, but was lovingly restored by the people at Vinegar Syndrome in 2019. Thank God they did, because the gore is a rare highlight, and almost all of the actually funny-on-purpose jokes are the ones where some disgusting bit of slapstick has just occurred. But put back into its place of privilege, the gore just amplifies the question of what the hell this film is doing. Is it kiddie schlock? Obnoxious douchey comedy for meanspirited high school bros? A gift to the gorehounds disappointed that Jurassic Park pulled its punches? Somehow, it's "yes" to all three, and the film is just as confounding as that triangulation implies.

In amidst all of its tonal problems, the fact that Tammy and the T-Rex is just plain bad filmmaking sort of doesn't register; there's a zesty enthusiasm to much of its badness that makes it feel more like a '50s or '60s B-movie than the kind of angrily mediocre crap getting spewed out direct-to-video in the '90s. There are some elements that are simply too tedious to pretend they're anything fun - in particular, Richard's performance is bad even compared to her reliably poor work in actual big-budget projects later in the decade and she's called upon to bear the entire emotional arc - but the more that it's just a dopey creature feature, the more playful it is. Michael the T-theRex is frequently fitted out with little rubber arms coming in from a side of the screen where they obviously don't match his body, while he does things like try to call Tammy on a pay phone (this is quite obviously the film's best scene); Kriser's performance as a generic mad scientist is the right kind of "antagonist on a Saturday morning kids' show" clowning around. I would not, on balance, say that Tammy and the T-Rex has enough of this kind of thing going on that it's ultimately a terribly watchable bad movie, but it has its moments, enough of them to look pretty good by the utterly dispiriting standards of '90s bad movies.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!