That deaf, dumb, and blind kid sure plays a mean pinball

A review requested by Gavin, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

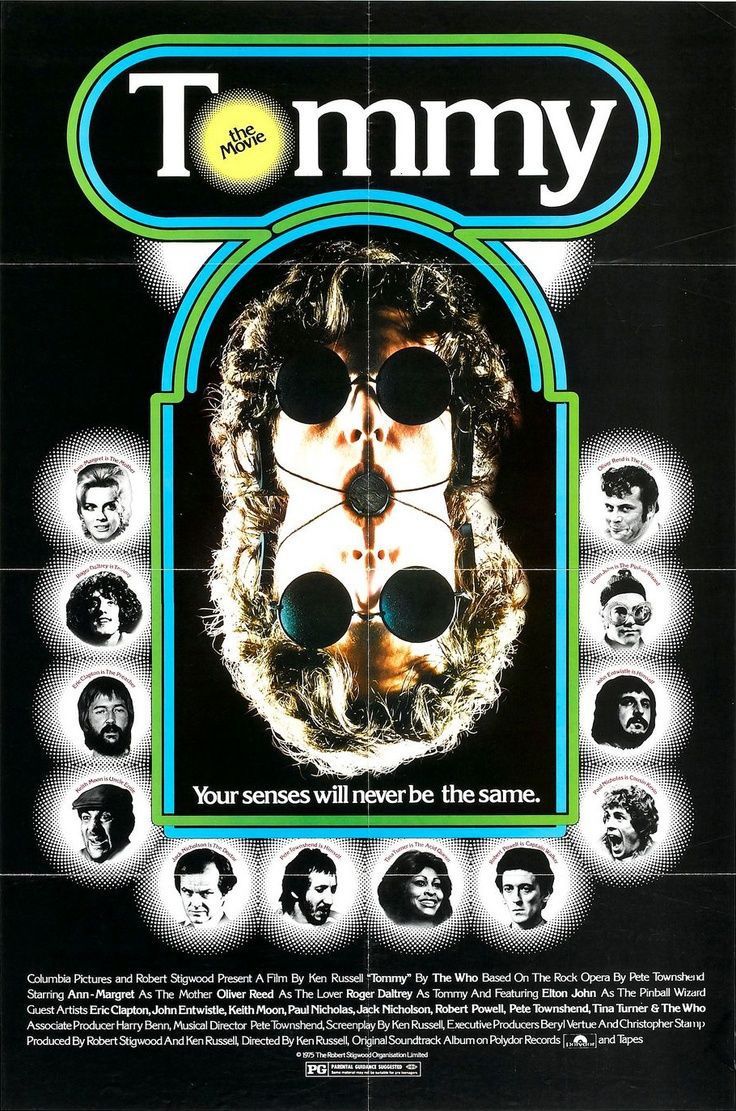

Tommy, the 1975 feature film adaptation of the 1969 concept album by The Who, is an erratic, garish mess. It would be an indescribable shame if that weren't the case.

For Tommy is, as its most basic level, a work of overweening excess. The album was a self-anointed "rock opera", one of the very first (the term dates to 1966, but no rock operas were successfully completed until 1968), and The Who - that is to say, the band's creative head, songwriter Pete Townshend - took that phrase as permission to create a sprawling wall of music in several genres, strapped around a narrative that's convoluted and elaborate while simultaneously being opaque and barely comprehensible if you don't know it in advance. It has a remarkable, maybe even unprecedented amount of ambition that could only go hand-in-hand with a compete fearlessness about coming off as ludicrous and goofy; more than it is good or bad as such, it is a work of sprawling grandeur (and for the record, I think it is extremely good; not The Who's best album, which is the 1971 follow-up Who's Next, but maybe the one that shows them off the best).

The story (which is slightly different in the film than in the movie) begins when Captain Walker (Robert Walker) is believed dead when his plane is shot down; his widow Nora (Ann-Margret) is thus left with a small boy, Tommy, to raise. She takes as a lover "Uncle" Frank (Oliver Reed), who agrees in his loutish way to be a father to the boy, but when the Captain returns, years after his presumed death, Nora and Frank murder him in a panic, and Tommy sees this. They tell the boy that he didn't see or hear anything, and he should never tell anybody about it, and Tommy, to cope with the trauma of seeing his long-lost father murdered, over-interprets this to mean that he can't see, hear, or say anything. And so he psychosomatically deaf, blind, and mute, not interacting with the rest of the world in any way until, as a young man (Roger Daltrey, lead singer of The Who), he turns out to be a pinball prodigy. The fame this brings to his family leads to a treatment where he confronts his trauma and turns into a pop-spiritual guru whose unconventional methods tap into the inexhaustible British propensity for bending the knee to authoritarians.

A proper film trying to wrangle this all into a visual form would need to be sprawling in its own right, and when producer Robert Stigwood began to go about turning the album into a movie, he made the absolute best possible choice of director available in the mid-'70s, grabbing the idiosyncratic visionary Ken Russell for the job. Russell had, by this point, firmly established himself as a specialist in films driven by music: he'd broken out with the 1962 docudrama Elgar, the first in an ongoing series of films about the lives of composers which had continued as recently with 1974 with the lightly fantastical Mahler. He'd also directed 1971's The Boy Friend, which was less an adaptation of Sandy Wilson's 1953 stage musical than a transfiguration of that material into a psychological horror comedy about the desperate inner lives of hustling actors. Tommy was already a fucked-up satire full of surrealistic flourishes and woozy, dreamy psychological portraiture; Russell didn't even have to work to make it a vehicle for all his characteristically warped visions.

And so it is that Tommy is, arguably, one of the director's least-radical efforts; compared to Lisztomania, which came out later the same year, it's downright safe, for example. But Ken Russell was also one of the least-safe filmmakers working in mainstream commercial cinema in the 1970s (indeed, one can barely imagine applying the adjectives "mainstream" or "commercial" to his work in any less adventurous decade), and even "playing nice for the studio" Russell, as we get here, is still a pretty loopy, madcap experience. I have already begged the question by proposing that he "wrangled" the album into a movie"; it would in fact be more accurate to claim that he made it even messier (a simple comparison works here: the album is 75 minutes, while the entirely sung-through film is 108 minutes). In its original version, Tommy attempted to be a story about trauma, grifting self-help culture, drugs as both a freeing and a destructive force, New Age philosophy, self-knowledge, religious cults, the hypocrisy of charismatic leaders who don't live by the own morality, and pinball. The movie is about all of those things, and Russell's script adds a major new layer: he sets the story 30 years later than the album, so that it's also about the generation of Britons born after the end of the Second World War, and the stark generational divide that created, along with the sense of moral uncertainty and social instability in which a generation of Baby Boomers uncomfortably came of age.

Again, messy as hell, and looking to Tommy in the hopes that it will provide a clear set of ideas about all of these themes, or any of them, can only end in sorrow. But that's never what the film is trying to do, and it makes absolutely no promises that we're going to walk out of it with a nice, tidy intellectual experience. Russell's project here is much more visceral and libidinal: he treats every song as a self-contained vignette, which he uses to blast a core idea, or a cluster of overlapping ideas, right at the audience with practically no modulation of force. The movie is a speeding train, visually overwhelming even in its "minimalist" sequences, and an all-out sonic attack. It was the one and only film using "Quintaphonic" sound, a five-channel surround system that largely resembles the much more successful 5.1 surround system, with the crucial absence of the bass track (the .1). The Quintaphonic mix was restored for the film's DVD release and subsequent Blu-ray, and as lucky as we are to have this chance to experience an oddity of film history, it's not a shock to learn that the technology didn't last: it sounds weird. The vocal tracks were cleanly separated out and placed in the center channel, which make the singing feel like it's floating in the ether, separate from the rest of the sounds; it's hollow and ghostly, and I'd swear it was post-dubbed with no real concern about good sync if I didn't know better. It works in this particular context, given the free-for-all unreality of the barely-there story, swamped by Russell's gaudy images; it creates the sense of the soundtrack as a collage designed separately from the image track, leaving it up to the individual viewer whether this is a musical experience or a visual one, whether the image and sound work in harmony or if they are both busily demanding our full attention.

Tommy is such an extreme non-stop rush of sensory overload, it hardly even registers at times that it's a narrative film with thematic ideas behind its plot. At the same time, Russell uses those themes as part of that same overload. The script, like the album but even moreso, is crammed to the brink with Ideas, and these are communicated in no small part through symbolism as heavy and obvious as I could possibly imagine. Most aggressively: Tommy wants to condemn pop culture consumerism for elevating celebrities to the status of philosophical leaders and quasi-religious icons (it was in fact the chance to make a film about a false messiah that attracted Russell to the project, not the album itself; by all accounts, and the evidence of the rest of his career, he didn't like rock music). So there's a scene set at a church where people kiss a statue of Marilyn Monroe to heal their diseases. And the statue breaks at the end of the scene, turning out to be hollow. There's not a molecule of subtlety here or anywhere else, and I do somewhat feel that Russell is guilty of making this a bit too easy and too literal; the film never, ever requires you to do any interpreting on your own. It is extremely obvious what it wants to communicate.

But again, that's party of the intense overload of muchness that the film traffics in throughout. The overriding goal of Tommy isn't to supply us with a clever, literary dissection of celebrity or religion or generational anomie or whatever; it is to hollow out our skull and fill it with a wild assortment of feverish imagery in the brightest colors the sludgy film stock of the 1970s can communicate. It gets at its themes viscerally, not intellectually; Russell might not have liked rock, but he understood that's how rock works.

So the whole film is pitched at 100%, whatever it's doing, regardless of whether what it's doing is working. Sometimes, it really doesn't: the Church of Marilyn is at least amusingly blunt, but it's still pretty dopey, and the melodramatic pantomime opening of Tommy's parents falling in love in a sun-dappled waterfall is actually excruciating. Who drummer Keith Moon's brief turn as the dissolute pedophile "Uncle" Ernie goes so hard for a monstrous, lizardlike extreme of slapstick perversity, delivered in a bellowing raspy voice, it's thoroughly exhausting. But thankfully, the great majority of the film does work, or at least is so energetically committed to its surrealism that "working" isn't a relative term. At least one moment, Elton John's performance of the album's best-known single, "Pinball Wizard", is legitimately perfect, with John's campy persona amplified to the breaking point, given the delightfully goofy accessory of a giant pair of boot-stilts, and accentuated by the snappiest editing that Stuart Baird provides to a film that is full of some radically quick and rhythmic cutting (impressively, this was Baird's first credit as lead editor, kicking off a terrific and influential career in that field, as well as a substantially less terrific career as director).

But the sequences in Tommy are like the weather: if you don't like one, it'll be different in five minutes. Every single number is doing something notably different, with the only constant that they are almost all more surreal than otherwise. Tina Turner (much less comfortable on-camera than Elton John, but her strain to act ends up working for the hostile energy of her song) appears in a menacingly Expressionist attic, and transforms into a chrome robot, that turns out to be an iron maiden, that transforms back into Tina Turner. Tommy's church of pinball is decorated with hilariously hideous modernist blocks of shapes that form a sort of Bauhaus parody of the Christian crucifix. A suburban bathroom is transformed in a kinky deathtrap of spikes, all coated in a toxic shade of piss yellow. Ann-Margret does... so much.

Ann-Margret gets her own paragraph, to hell with it. This is not a film about its humans; I don't even know what "good acting" would look like in this context. We don't get it from either of the other leads: Daltrey obviously had no clue how to act, so he basically just acts as Russell's poseable doll. Reed, who had previously worked with Russell in the radically sexual 1969 adaptation of D.H. Lawrence's Women in Love, and the all-around radical 1971 nunsploitation art film The Devils, obviously figured out immediately that this was going to be pitched as florid kitsch, and accordingly just played things as a big, self-satisfied ham. Ann-Margret, however, has given so much of herself, trying to match every one of the film's massive stylistic and tonal swerves with one of her own. I don't think she was ever anyone's idea of a great actor, and maybe that's not even what's going on here, but it is astonishingly committed, whatever the hell it is. She comes awfully close to making the pantomime opening work, beaming with virginal lightness; that sets up an arc found nowhere in the album that eventually finds her orgasmically writhing around in soap suds and baked beans, the one place where Russell's tendency towards kink really shows up in the film. In the middle, she plays an actual grounded character note when she lets us see Nora's pragmatic embrace of Frank as a necessary evil, who must never realise that she thinks of him that way. She sinks into middle-class resignation letting her face melt like a cheap mask as she applies make-up and messily slurs her way through the line "Do you think it's alright?", which has been altered from its single appearance on the album to serve as a recurring motif that watches the character give in to the path of least resistance as her emotional commitment to Tommy wanes and waxes. It's a sloppy, throw-it-all-at-the-wall performance, one that would be mortifying if Ann-Margret seemed any less than 100% invested in the film's weird energies, and somehow, this ends up providing the entire film with a foundation in something human. For this, she received an Oscar nomination for Best Actress - 1975 was the most oddball year in that category's entire history, and this is still the "weird" one in that group, and almost certainly the single strangest performance ever nominated for an Academy Award.

Ann-Margret is Tommy in a microcosm: fearless, a grotesque caricature of humanity that plays everything to the rafters, and utterly electrifying and magnetic if you're on the right wavelength. Which, I think, is not too hard to be; this is certainly the "friendliest" Ken Russell film I have seen, if only by virtue of having wall-to-wall songs from one of the most popular rock bands in history performed by an all-star cast (Eric Clapton also shows up. As does Jack Nicholson, because Russell wasn't going to let something silly like "a total inability to sing" get in the way of the peculiar mood he was looking for). It's also not challenging - off-putting, maybe, especially if concepts like "Ann-Margret simulates sex while swimming through baked beans" is off-putting to you for some peculiar reason. But you don't have to work for it; the film has done all of that for us. Which maybe speaks poorly of the film, but given what an absolute roller coaster of giddy images and raging sounds Tommy is, having to actually stop and think about it while you're watching would probably be too much to handle.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

Tommy, the 1975 feature film adaptation of the 1969 concept album by The Who, is an erratic, garish mess. It would be an indescribable shame if that weren't the case.

For Tommy is, as its most basic level, a work of overweening excess. The album was a self-anointed "rock opera", one of the very first (the term dates to 1966, but no rock operas were successfully completed until 1968), and The Who - that is to say, the band's creative head, songwriter Pete Townshend - took that phrase as permission to create a sprawling wall of music in several genres, strapped around a narrative that's convoluted and elaborate while simultaneously being opaque and barely comprehensible if you don't know it in advance. It has a remarkable, maybe even unprecedented amount of ambition that could only go hand-in-hand with a compete fearlessness about coming off as ludicrous and goofy; more than it is good or bad as such, it is a work of sprawling grandeur (and for the record, I think it is extremely good; not The Who's best album, which is the 1971 follow-up Who's Next, but maybe the one that shows them off the best).

The story (which is slightly different in the film than in the movie) begins when Captain Walker (Robert Walker) is believed dead when his plane is shot down; his widow Nora (Ann-Margret) is thus left with a small boy, Tommy, to raise. She takes as a lover "Uncle" Frank (Oliver Reed), who agrees in his loutish way to be a father to the boy, but when the Captain returns, years after his presumed death, Nora and Frank murder him in a panic, and Tommy sees this. They tell the boy that he didn't see or hear anything, and he should never tell anybody about it, and Tommy, to cope with the trauma of seeing his long-lost father murdered, over-interprets this to mean that he can't see, hear, or say anything. And so he psychosomatically deaf, blind, and mute, not interacting with the rest of the world in any way until, as a young man (Roger Daltrey, lead singer of The Who), he turns out to be a pinball prodigy. The fame this brings to his family leads to a treatment where he confronts his trauma and turns into a pop-spiritual guru whose unconventional methods tap into the inexhaustible British propensity for bending the knee to authoritarians.

A proper film trying to wrangle this all into a visual form would need to be sprawling in its own right, and when producer Robert Stigwood began to go about turning the album into a movie, he made the absolute best possible choice of director available in the mid-'70s, grabbing the idiosyncratic visionary Ken Russell for the job. Russell had, by this point, firmly established himself as a specialist in films driven by music: he'd broken out with the 1962 docudrama Elgar, the first in an ongoing series of films about the lives of composers which had continued as recently with 1974 with the lightly fantastical Mahler. He'd also directed 1971's The Boy Friend, which was less an adaptation of Sandy Wilson's 1953 stage musical than a transfiguration of that material into a psychological horror comedy about the desperate inner lives of hustling actors. Tommy was already a fucked-up satire full of surrealistic flourishes and woozy, dreamy psychological portraiture; Russell didn't even have to work to make it a vehicle for all his characteristically warped visions.

And so it is that Tommy is, arguably, one of the director's least-radical efforts; compared to Lisztomania, which came out later the same year, it's downright safe, for example. But Ken Russell was also one of the least-safe filmmakers working in mainstream commercial cinema in the 1970s (indeed, one can barely imagine applying the adjectives "mainstream" or "commercial" to his work in any less adventurous decade), and even "playing nice for the studio" Russell, as we get here, is still a pretty loopy, madcap experience. I have already begged the question by proposing that he "wrangled" the album into a movie"; it would in fact be more accurate to claim that he made it even messier (a simple comparison works here: the album is 75 minutes, while the entirely sung-through film is 108 minutes). In its original version, Tommy attempted to be a story about trauma, grifting self-help culture, drugs as both a freeing and a destructive force, New Age philosophy, self-knowledge, religious cults, the hypocrisy of charismatic leaders who don't live by the own morality, and pinball. The movie is about all of those things, and Russell's script adds a major new layer: he sets the story 30 years later than the album, so that it's also about the generation of Britons born after the end of the Second World War, and the stark generational divide that created, along with the sense of moral uncertainty and social instability in which a generation of Baby Boomers uncomfortably came of age.

Again, messy as hell, and looking to Tommy in the hopes that it will provide a clear set of ideas about all of these themes, or any of them, can only end in sorrow. But that's never what the film is trying to do, and it makes absolutely no promises that we're going to walk out of it with a nice, tidy intellectual experience. Russell's project here is much more visceral and libidinal: he treats every song as a self-contained vignette, which he uses to blast a core idea, or a cluster of overlapping ideas, right at the audience with practically no modulation of force. The movie is a speeding train, visually overwhelming even in its "minimalist" sequences, and an all-out sonic attack. It was the one and only film using "Quintaphonic" sound, a five-channel surround system that largely resembles the much more successful 5.1 surround system, with the crucial absence of the bass track (the .1). The Quintaphonic mix was restored for the film's DVD release and subsequent Blu-ray, and as lucky as we are to have this chance to experience an oddity of film history, it's not a shock to learn that the technology didn't last: it sounds weird. The vocal tracks were cleanly separated out and placed in the center channel, which make the singing feel like it's floating in the ether, separate from the rest of the sounds; it's hollow and ghostly, and I'd swear it was post-dubbed with no real concern about good sync if I didn't know better. It works in this particular context, given the free-for-all unreality of the barely-there story, swamped by Russell's gaudy images; it creates the sense of the soundtrack as a collage designed separately from the image track, leaving it up to the individual viewer whether this is a musical experience or a visual one, whether the image and sound work in harmony or if they are both busily demanding our full attention.

Tommy is such an extreme non-stop rush of sensory overload, it hardly even registers at times that it's a narrative film with thematic ideas behind its plot. At the same time, Russell uses those themes as part of that same overload. The script, like the album but even moreso, is crammed to the brink with Ideas, and these are communicated in no small part through symbolism as heavy and obvious as I could possibly imagine. Most aggressively: Tommy wants to condemn pop culture consumerism for elevating celebrities to the status of philosophical leaders and quasi-religious icons (it was in fact the chance to make a film about a false messiah that attracted Russell to the project, not the album itself; by all accounts, and the evidence of the rest of his career, he didn't like rock music). So there's a scene set at a church where people kiss a statue of Marilyn Monroe to heal their diseases. And the statue breaks at the end of the scene, turning out to be hollow. There's not a molecule of subtlety here or anywhere else, and I do somewhat feel that Russell is guilty of making this a bit too easy and too literal; the film never, ever requires you to do any interpreting on your own. It is extremely obvious what it wants to communicate.

But again, that's party of the intense overload of muchness that the film traffics in throughout. The overriding goal of Tommy isn't to supply us with a clever, literary dissection of celebrity or religion or generational anomie or whatever; it is to hollow out our skull and fill it with a wild assortment of feverish imagery in the brightest colors the sludgy film stock of the 1970s can communicate. It gets at its themes viscerally, not intellectually; Russell might not have liked rock, but he understood that's how rock works.

So the whole film is pitched at 100%, whatever it's doing, regardless of whether what it's doing is working. Sometimes, it really doesn't: the Church of Marilyn is at least amusingly blunt, but it's still pretty dopey, and the melodramatic pantomime opening of Tommy's parents falling in love in a sun-dappled waterfall is actually excruciating. Who drummer Keith Moon's brief turn as the dissolute pedophile "Uncle" Ernie goes so hard for a monstrous, lizardlike extreme of slapstick perversity, delivered in a bellowing raspy voice, it's thoroughly exhausting. But thankfully, the great majority of the film does work, or at least is so energetically committed to its surrealism that "working" isn't a relative term. At least one moment, Elton John's performance of the album's best-known single, "Pinball Wizard", is legitimately perfect, with John's campy persona amplified to the breaking point, given the delightfully goofy accessory of a giant pair of boot-stilts, and accentuated by the snappiest editing that Stuart Baird provides to a film that is full of some radically quick and rhythmic cutting (impressively, this was Baird's first credit as lead editor, kicking off a terrific and influential career in that field, as well as a substantially less terrific career as director).

But the sequences in Tommy are like the weather: if you don't like one, it'll be different in five minutes. Every single number is doing something notably different, with the only constant that they are almost all more surreal than otherwise. Tina Turner (much less comfortable on-camera than Elton John, but her strain to act ends up working for the hostile energy of her song) appears in a menacingly Expressionist attic, and transforms into a chrome robot, that turns out to be an iron maiden, that transforms back into Tina Turner. Tommy's church of pinball is decorated with hilariously hideous modernist blocks of shapes that form a sort of Bauhaus parody of the Christian crucifix. A suburban bathroom is transformed in a kinky deathtrap of spikes, all coated in a toxic shade of piss yellow. Ann-Margret does... so much.

Ann-Margret gets her own paragraph, to hell with it. This is not a film about its humans; I don't even know what "good acting" would look like in this context. We don't get it from either of the other leads: Daltrey obviously had no clue how to act, so he basically just acts as Russell's poseable doll. Reed, who had previously worked with Russell in the radically sexual 1969 adaptation of D.H. Lawrence's Women in Love, and the all-around radical 1971 nunsploitation art film The Devils, obviously figured out immediately that this was going to be pitched as florid kitsch, and accordingly just played things as a big, self-satisfied ham. Ann-Margret, however, has given so much of herself, trying to match every one of the film's massive stylistic and tonal swerves with one of her own. I don't think she was ever anyone's idea of a great actor, and maybe that's not even what's going on here, but it is astonishingly committed, whatever the hell it is. She comes awfully close to making the pantomime opening work, beaming with virginal lightness; that sets up an arc found nowhere in the album that eventually finds her orgasmically writhing around in soap suds and baked beans, the one place where Russell's tendency towards kink really shows up in the film. In the middle, she plays an actual grounded character note when she lets us see Nora's pragmatic embrace of Frank as a necessary evil, who must never realise that she thinks of him that way. She sinks into middle-class resignation letting her face melt like a cheap mask as she applies make-up and messily slurs her way through the line "Do you think it's alright?", which has been altered from its single appearance on the album to serve as a recurring motif that watches the character give in to the path of least resistance as her emotional commitment to Tommy wanes and waxes. It's a sloppy, throw-it-all-at-the-wall performance, one that would be mortifying if Ann-Margret seemed any less than 100% invested in the film's weird energies, and somehow, this ends up providing the entire film with a foundation in something human. For this, she received an Oscar nomination for Best Actress - 1975 was the most oddball year in that category's entire history, and this is still the "weird" one in that group, and almost certainly the single strangest performance ever nominated for an Academy Award.

Ann-Margret is Tommy in a microcosm: fearless, a grotesque caricature of humanity that plays everything to the rafters, and utterly electrifying and magnetic if you're on the right wavelength. Which, I think, is not too hard to be; this is certainly the "friendliest" Ken Russell film I have seen, if only by virtue of having wall-to-wall songs from one of the most popular rock bands in history performed by an all-star cast (Eric Clapton also shows up. As does Jack Nicholson, because Russell wasn't going to let something silly like "a total inability to sing" get in the way of the peculiar mood he was looking for). It's also not challenging - off-putting, maybe, especially if concepts like "Ann-Margret simulates sex while swimming through baked beans" is off-putting to you for some peculiar reason. But you don't have to work for it; the film has done all of that for us. Which maybe speaks poorly of the film, but given what an absolute roller coaster of giddy images and raging sounds Tommy is, having to actually stop and think about it while you're watching would probably be too much to handle.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.